AFR 49/001/2002 Senegal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Senegal, Between Migrations to Europe and Returns

The ITPCM International Commentary Vol. X no. 35 ISSN. 2239-7949 in this issue: in this issue: SENEGALSENEGAL BETWEEN MIGRATIONS TO EUROPE AND RETURNS April 2014 1 ITPCM International Commentary April 2014 ISSN. 2239-7949 International Training Programme for Conflict Management ITPCM International Commentary April 2014 ISSN. 2239-7949 The ITPCM International Commentary SENEGAL BETWEEN MIGRATIONS TO EUROPE AND RETURNS April 2014 ITPCM International Commentary April 2014 ISSN. 2239-7949 Table of Contents For an Introduction - Senegalese Street Vendors and the Migration and Development Nexus by Michele Gonnelli, p. 8 The Senegalese Transnational The Policy Fallacy of promoting Diaspora and its role back Home Return migration among by Sebastiano Ceschi & Petra Mezzetti, p. 13 Senegalese Transnationals by Alpha Diedhiou, p. 53 Imagining Europe: being willing to go does not necessarily result The PAISD: an adaptive learning in taking the necessary Steps process to the Migration & by Papa Demba Fall, p. 21 Development nexus by Francesca Datola, p. 59 EU Migration Policies and the Criminalisation of the Senegalese The local-to-local dimension of Irregular Migration flows the Migration & Development by Lanre Olusegun Ikuteyijo, p. 29 nexus by Amadou Lamine Cissé and Reframing Senegalese Youth and Jo-Lind Roberts, p. 67 Clandestine Migration to a utopian Europe Fondazioni4Africa promotes co- by Jayne O. Ifekwunigwe, p. 35 development by partnering Migrant Associations Senegalese Values and other by Marzia Sica & Ilaria Caramia, p. 73 cultural Push Pull Factors behind migration and return Switching Perspectives: South- by Ndioro Ndiaye, p. 41 South Migration and Human Development in Senegal Returns and Reintegrations in by Jette Christiansen & Livia Manente, p. -

Joola Dynamics Between Senegal and Guinea-Bissau Jordi Tomàs (CEA-ISCTE) Paper Presented at ABORNE Fifth Annual Conference, Lisbon, September 22Th, 2011

THIS IS REALLY A PRELIMINARY DRAFT. NOT FOR CITATION OR CIRCULATION WITHOUT AUTHOR’S PERMISSION, PLEASE An international border or just a territorial limit? Joola dynamics between Senegal and Guinea-Bissau Jordi Tomàs (CEA-ISCTE) Paper presented at ABORNE Fifth Annual Conference, Lisbon, September 22th, 2011. Introduction This paper aims to present an ongoing research about the dynamics of Joola population in the border between Guinea-Bissau and Senegal (more specifically from the Atlantic Ocean to the Niambalang river). We would like to tell you about how Joola Ajamaat (near the main town of Susanna, Guinea-Bissau) and Joola Huluf (near the main town of Oussouye, Senegal) define the border and, especially, how they use this border in their daily lives1. As most borderland regions in the Upper Guinea Coast, this international border separates two areas that have been economically and politically marginalised within their respective national contexts (Senegal and Guinea-Bissau) in colonial and postcolonial times. Moreover, from 1982 –that is, for almost 30 years– this border area has suffered the conflict between the separatist MFDC (Mouvement des Forces Démocratiques de Casamance) and the Senegalese army (and, in the last few years, the Bissau-Guinean army as well). Despite this situation, the links between the population on both sides are still alive, as we will show later on. After a short historical presentation, we would like to focus on three main subjects. First, to show concrete examples of everyday life gathered during our fieldwork. Secondly, to see how the conflict have affected the relationship between the Joola from both sides of 1 This paper has been made possible thanks to a postdoctoral scholarship granted by FCT (Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia). -

Road Travel Report: Senegal

ROAD TRAVEL REPORT: SENEGAL KNOW BEFORE YOU GO… Road crashes are the greatest danger to travelers in Dakar, especially at night. Traffic seems chaotic to many U.S. drivers, especially in Dakar. Driving defensively is strongly recommended. Be alert for cyclists, motorcyclists, pedestrians, livestock and animal-drawn carts in both urban and rural areas. The government is gradually upgrading existing roads and constructing new roads. Road crashes are one of the leading causes of injury and An average of 9,600 road crashes involving injury to death in Senegal. persons occur annually, almost half of which take place in urban areas. There are 42.7 fatalities per 10,000 vehicles in Senegal, compared to 1.9 in the United States and 1.4 in the United Kingdom. ROAD REALITIES DRIVER BEHAVIORS There are 15,000 km of roads in Senegal, of which 4, Drivers often drive aggressively, speed, tailgate, make 555 km are paved. About 28% of paved roads are in fair unexpected maneuvers, disregard road markings and to good condition. pass recklessly even in the face of oncoming traffic. Most roads are two-lane, narrow and lack shoulders. Many drivers do not obey road signs, traffic signals, or Paved roads linking major cities are generally in fair to other traffic rules. good condition for daytime travel. Night travel is risky Drivers commonly try to fit two or more lanes of traffic due to inadequate lighting, variable road conditions and into one lane. the many pedestrians and non-motorized vehicles sharing the roads. Drivers commonly drive on wider sidewalks. Be alert for motorcyclists and moped riders on narrow Secondary roads may be in poor condition, especially sidewalks. -

Ni Paix Ni Guerre: the Political Economy of Low-Level Conflict in The

Overseas Development Institute HPG Background Paper Ni paix ni guerre: the political The Humanitarian Policy Group at HUMANITARIAN economy of low-levelthe Overseas conflictDevelopment POLICYInstitute GROUP is Europe’s leading team of independent policy researchers in the Casamancededicated to improving humanitarian policy and practice Martin Evans in response to conflict, instability and disasters. Department of Geography King’s College London Background research for HPG Report 13 February 2003 HPG BACKGROUND PAPER Abstract The Casamance is the southern limb of Senegal and an area rich in agricultural and forest resources. Since 1982, it has witnessed a separatist rebellion by the Mouvement des forces démocratiques de la Casamance (MFDC). This case study focuses on the ‘war economy’ established during the period of serious conflict (since 1990), principally in Ziguinchor region, and based mainly on natural resources such as timber, tree crops and cannabis. Members of the MFDC guerrilla group, Senega- lese forces and civilians, together with elements from neighbouring Guinea-Bissau and The Gam- bia, are implicated. However, the majority of Casamançais suffer because of exclusion from pro- ductive resources and regional economic crisis resulting from the conflict. The war economy may also be obstructing the current peace process, with vested interests profiting from ongoing, low- level conflict, at a time when donors and agencies are returning. This case study therefore aims to describe the war economy in terms of the actors and commodities -

A Case Comparison of Ghana, Kenya, and Senegal

1 Democratization and Universal Health Coverage: A Case Comparison of Ghana, Kenya, and Senegal Karen A. Grépin and Kim Yi Dionne This article identifies conditions under which newly established democracies adopt Universal Health Coverage. Drawing on the literature examining democracy and health, we argue that more democratic regimes – where citizens have positive opinions on democracy and where competitive, free and fair elections put pressure on incumbents – will choose health policies targeting a broader proportion of the population. We compare Ghana to Kenya and Senegal, two other countries which have also undergone democratization, but where there have been important differences in the extent to which these democratic changes have been perceived by regular citizens and have translated into electoral competition. We find that Ghana has adopted the most ambitious health reform strategy by designing and implementing the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS). We also find that Ghana experienced greater improvements in skilled attendance at birth, childhood immunizations, and improvements in the proportion of children with diarrhea treated by oral rehydration therapy than the other countries since this policy was adopted. These changes also appear to be associated with important changes in health outcomes: both infant and under-five mortality rates declined rapidly since the introduction of the NHIS in Ghana. These improvements in health and health service delivery have also been observed by citizens with a greater proportion of Ghanaians reporting satisfaction with government handling of health service delivery relative to either Kenya or Senegal. We argue that the democratization process can promote the adoption of particular health policies and that this is an important mechanism through which democracy can improve health. -

Communauté Rurale OULAMPANE

République du Sénégal Un peuple – Un but – Une foi MINISTERE DE L’HABITAT, DE LA MINISTERE DE L’URBANISME ET DE CONSTRUCTION ET DE L’HYDRAULIQUE L’ASSAINISSEMENT Région de ZIGUINCHOR PLAN LOCAL D’HYDRAULIQUE ET D’ASSAINISSEMENT -PLHA Communauté rurale OULAMPANE (Version finale) JUILLET 2010 Ce document est réalisé sur financement de l’Agence Américaine pour le Développement International (USAID) dans le cadre de son appui au Gouvernement du Sénégal 1 USAID/PEPAM Millennium Water and Sanitation Program Programme d’Eau Potable et d’Assainissement du Millénaire Cooperative Agreement No 685-A-00-09-00006-00 Accord de cooperation n°685-A-00-09-00006-00 PREPARED FOR / PRÉPARÉ À L’ATTENTION DE Prepared by / Préparé par Agathe Sector RTI International Agreement Officer’s Representative 3040 Cornwallis Road Office of Economic Growth Post Office Box 12194 USAID/Senegal Research Triangle Park, NC 27709-2194 Route des Almadies Phone: 919.541.6000 Almadies BP 49 Dakar, Senegal http://www.rti.org SOMMAIRE SOMMAIRE ........................................................................................................................................................... 2 LISTE DES ABREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................................. 4 FICHE DE SYNTHESE PLHA............................................................................................................................ 5 I. PRÉSENTATION DE LA COMMUNAUTÉ RURALE ................................................................................ -

Governance of Protected Areas from Understanding to Action

Governance of Protected Areas From understanding to action Grazia Borrini-Feyerabend, Nigel Dudley, Tilman Jaeger, Barbara Lassen, Neema Pathak Broome, Adrian Phillips and Trevor Sandwith Developing capacity for a protected planet Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines Series No.20 IUCN WCPA’s BEST PRACTICE PROTECTED AREA GUIDELINES SERIES IUCN-WCPA’s Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines are the world’s authoritative resource for protected area managers. Involving collaboration among specialist practitioners dedicated to supporting better implementation in the field, they distil learning and advice drawn from across IUCN. Applied in the field, they are building institutional and individual capacity to manage protected area systems effectively, equitably and sustainably, and to cope with the myriad of challenges faced in practice. They also assist national governments, protected area agencies, non- governmental organisations, communities and private sector partners to meet their commitments and goals, and especially the Convention on Biological Diversity’s Programme of Work on Protected Areas. A full set of guidelines is available at: www.iucn.org/pa_guidelines Complementary resources are available at: www.cbd.int/protected/tools/ Contribute to developing capacity for a Protected Planet at: www.protectedplanet.net/ IUCN PROTECTED AREA DEFINITION, MANAGEMENT CATEGORIES AND GOVERNANCE TYPES IUCN defines a protected area as: A clearly defined geographical space, recognised, dedicated and managed, through legal or other effective means, -

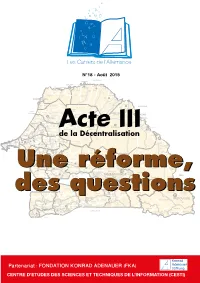

Acte III Une Réforme, Des Questions Une Réforme, Des Questions

N°18 - Août 2015 MAURITANIE PODOR DAGANA Gamadji Sarré Dodel Rosso Sénégal Ndiandane Richard Toll Thillé Boubakar Guédé Ndioum Village Ronkh Gaé Aéré Lao Cas Cas Ross Béthio Mbane Fanaye Ndiayène Mboumba Pendao Golléré SAINT-LOUIS Région de Madina Saldé Ndiatbé SAINT-LOUIS Pété Galoya Syer Thilogne Gandon Mpal Keur Momar Sar Région de Toucouleur MAURITANIE Tessekéré Forage SAINT-LOUIS Rao Agnam Civol Dabia Bokidiawé Sakal Région de Océan LOUGA Léona Nguène Sar Nguer Malal Gandé Mboula Labgar Oréfondé Nabbadji Civol Atlantique Niomré Région de Mbeuleukhé MATAM Pété Ouarack MATAM Kelle Yang-Yang Dodji Gueye Thieppe Bandègne KANEL LOUGA Lougré Thiolly Coki Ogo Ouolof Mbédiène Kamb Géoul Thiamène Diokoul Diawrigne Ndiagne Kanène Cayor Boulal Thiolom KEBEMER Ndiob Thiamène Djolof Ouakhokh Région de Fall Sinthiou Loro Touba Sam LOUGA Bamambé Ndande Sagata Ménina Yabal Dahra Ngandiouf Geth BarkedjiRégion de RANEROU Ndoyenne Orkadiéré Waoundé Sagatta Dioloff Mboro Darou Mbayène Darou LOUGA Khoudoss Semme Méouane Médina Pékesse Mamane Thiargny Dakhar MbadianeActe III Moudéry Taïba Pire Niakhène Thimakha Ndiaye Gourèye Koul Darou Mousty Déali Notto Gouye DiawaraBokiladji Diama Pambal TIVAOUANE de la DécentralisationRégion de Kayar Diender Mont Rolland Chérif Lô MATAM Guedj Vélingara Oudalaye Wourou Sidy Aouré Touba Région de Thiel Fandène Thiénaba Toul Région de Pout Région de DIOURBEL Région de Gassane khombole Région de Région de DAKAR DIOURBEL Keur Ngoundiane DIOURBEL LOUGA MATAM Gabou Moussa Notto Ndiayène THIES Sirah Région de Ballou Ndiass -

Urban Guerrilla Poetry: the Movement Y' En a Marre and the Socio

Urban Guerrilla Poetry: The Movement Y’ en a Marre and the Socio-Political Influences of Hip Hop in Senegal by Marame Gueye Marame Gueye is an assistant professor of African and African diaspora literatures at East Carolina University. She received a doctorate in Comparative Literature, Feminist Theory, and Translation from SUNY Binghamton with a dissertation entitled: Wolof Wedding Songs: Women Negotiating Voice and Space Trough Verbal Art . Her research interests are orality, verbal art, immigration, and gender and translation discourses. Her most recent article is “ Modern Media and Culture: Speaking Truth to Power” in African Studies Review (vol. 54, no.3). Abstract Since the 1980s, Hip Hop has become a popular musical genre in most African countries. In Senegal, young artists have used the genre as a mode of social commentary by vesting their aesthetics in the culture’s oral traditions established by griots. However, starting from the year 2000, Senegalese Hip Hop evolved as a platform for young people to be politically engaged and socially active. This socio-political engagement was brought to a higher level during the recent presidential elections when Hip Hop artists created the Y’En a Marre Movement [Enough is Enough]. The movement emerged out of young people’s frustrations with the chronic power cuts that plagued Senegal since 2003 to becoming the major critic of incumbent President Abdoulaye Wade. Y’en Marre was at the forefront of major demonstrations against Wade’s bid for a contested third term. But of greater or equal importance, the movement’s musical releases during the period were specifically aimed at “bringing down the president.” This article looks at their last installment piece entitled Faux! Pas Forcé [Fake! Forced Step or Don’t! Push] which was released at the eve of the second round of voting. -

Download.Aspx?Symbolno=CAT/C/SEN/CO/3&Lan G=En>, (Last Consulted April 2015)

SENEGAL: FAILING TO LIVE UP TO ITS PROMISES RECOMMENDATIONS ON THE EVE OF THE AFRICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN AND PEOPLES’ RIGHTS’ REVIEW OF SENEGAL 56TH SESSION, APRIL- MAY 2015 Amnesty International Publications First published in 2015 by Amnesty International, West and Central Africa Regional Office Immeuble Seydi Djamil, Avenue Cheikh Anta Diop x 3, rue Frobenius 3e Etage BP. 47582 Dakar, Liberté Sénégal www.amnesty.org © Amnesty International Publications 2015 Index: AFR 49/1464/2015 Original Language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................................. 4 Follow-up to the 2003 Review....................................................................................... -

'Niŋ, -Pi-, -E and -Aa Morphemes in Kuloonay

The prefix ni- in Kuloonaay: grammaticalization pathways in a three-morpheme system By David C. Lowry August 2015 Word Count: 19,719 Presented as part of the requirement of the MA Degree in Field Linguistics, Centre for Linguistics, Translation & Literacy, Redcliffe College. DECLARATION This dissertation is the product of my own work. I declare also that the dissertation is available for photocopying, reference purposes and Inter-Library Loan. David Christopher Lowry 2 ABSTRACT Title: The prefix ni- in Kuloonaay: grammaticalization pathways in a three- morpheme system. Author: David C. Lowry Date: August 2015 The prefix ni- is the most common particle in the verbal system of Jola Kuloonaay, an Atlantic language of Senegal and The Gambia. Its complex distribution has made it difficult to classify, and a variety of labels have been proposed in the literature. Other authors writing on Kuloonaay and on related Jola languages have described this prefix in terms of a single morpheme whose distribution follows an eclectic list of rules for which the synchronic motivation is not obvious. An alternative approach, presented here, is to describe the ni- prefix in terms of three distinct morphemes, each following a simple set of rules within a restricted domain. This study explores the three-morpheme hypothesis from both a synchronic and a diachronic perspective. At a synchronic level, a small corpus of narrative texts is used to verify that the model proposed corresponds to the behaviour of ni- in natural text. At a diachronic level, data from a selection of other Jola languages is drawn upon in order to gain insight into the grammaticalization pathways by which the three morpheme ni- system may have evolved. -

Livelihood Zone Descriptions

Government of Senegal COMPREHENSIVE FOOD SECURITY AND VULNERABILITY ANALYSIS (CFSVA) Livelihood Zone Descriptions WFP/FAO/SE-CNSA/CSE/FEWS NET Introduction The WFP, FAO, CSE (Centre de Suivi Ecologique), SE/CNSA (Commissariat National à la Sécurité Alimentaire) and FEWS NET conducted a zoning exercise with the goal of defining zones with fairly homogenous livelihoods in order to better monitor vulnerability and early warning indicators. This exercise led to the development of a Livelihood Zone Map, showing zones within which people share broadly the same pattern of livelihood and means of subsistence. These zones are characterized by the following three factors, which influence household food consumption and are integral to analyzing vulnerability: 1) Geography – natural (topography, altitude, soil, climate, vegetation, waterways, etc.) and infrastructure (roads, railroads, telecommunications, etc.) 2) Production – agricultural, agro-pastoral, pastoral, and cash crop systems, based on local labor, hunter-gatherers, etc. 3) Market access/trade – ability to trade, sell goods and services, and find employment. Key factors include demand, the effectiveness of marketing systems, and the existence of basic infrastructure. Methodology The zoning exercise consisted of three important steps: 1) Document review and compilation of secondary data to constitute a working base and triangulate information 2) Consultations with national-level contacts to draft initial livelihood zone maps and descriptions 3) Consultations with contacts during workshops in each region to revise maps and descriptions. 1. Consolidating secondary data Work with national- and regional-level contacts was facilitated by a document review and compilation of secondary data on aspects of topography, production systems/land use, land and vegetation, and population density.