Evidentiality in Lithuanian Gronemeyer, Claire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Politics of Revolutionary Anti-Imperialism

FIRE THE POLITICS OF REVOLUTIONARY ANTI-IMPERIALISM ---- - ... POLITICAL STATEMENT OF THE UND£ $1.50 Prairie Fire Distributing Lo,rnrrntte:e This edition ofPrairie Fire is published and copyrighted by Communications Co. in response to a written request from the authors of the contents. 'rVe have attempted to produce a readable pocket size book at a re'ls(m,tbl.e cost. Weare printing as many as fast as limited resources allow. We hope that people interested in Revolutionary ideas and events will morc and better editions possible in the future. (And that this edition at least some extent the request made by its authors.) PO Box 411 Communications Co. Times Plaza Sta. PO Box 40614, Sta. C Brooklyn, New York San FrancisQ:O, Ca. 11217 94110 Quantity rates upon request to Peoples' Bookstores and Community organiza- tlOBS. PRAIRIE FIRE THE POLITICS OF REVOLUTIONARY ANTI-IMPERIALISM POLITICAL STATEMENT , OF THE WEATHER Copyright © 1974 by Communications Co. UNDERGROUND All rights reserved The pUblisher's copyright is not intended to discourage the use ofmaterial from this book for political debate and study. It is intended to prevent false and distorted reproduction and profiteering. Aside from those limits, people are free to utilize the material. This edition is a copy of the original which was Printed Underground In the US For The People Published by Communications Co. 1974 +h(~ of OlJr(1)mYl\Q~S tJ,o ~Q.Ve., ~·Ir tllJ€~ it) #i s\-~~\~ 'Yt)l1(ch ~, \~ 10 ~~\ d~~~ee.' l1~rJ 1I'bw~· reU'w) ~it· e\rrp- f'0nit'l)o yralt· ~YZlpmu>I')' ca~-\e.v"C2lmp· ~~ ~[\.ll10' ~li~ ~n. -

Imaginative Geographies of Mars: the Science and Significance of the Red Planet, 1877 - 1910

Copyright by Kristina Maria Doyle Lane 2006 The Dissertation Committee for Kristina Maria Doyle Lane Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: IMAGINATIVE GEOGRAPHIES OF MARS: THE SCIENCE AND SIGNIFICANCE OF THE RED PLANET, 1877 - 1910 Committee: Ian R. Manners, Supervisor Kelley A. Crews-Meyer Diana K. Davis Roger Hart Steven D. Hoelscher Imaginative Geographies of Mars: The Science and Significance of the Red Planet, 1877 - 1910 by Kristina Maria Doyle Lane, B.A.; M.S.C.R.P. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2006 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to Magdalena Maria Kost, who probably never would have understood why it had to be written and certainly would not have wanted to read it, but who would have been very proud nonetheless. Acknowledgments This dissertation would have been impossible without the assistance of many extremely capable and accommodating professionals. For patiently guiding me in the early research phases and then responding to countless followup email messages, I would like to thank Antoinette Beiser and Marty Hecht of the Lowell Observatory Library and Archives at Flagstaff. For introducing me to the many treasures held deep underground in our nation’s capital, I would like to thank Pam VanEe and Ed Redmond of the Geography and Map Division of the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. For welcoming me during two brief but productive visits to the most beautiful library I have seen, I thank Brenda Corbin and Gregory Shelton of the U.S. -

Definiteness Determined by Syntax: a Case Study in Tagalog 1 Introduction

Definiteness determined by syntax: A case study in Tagalog1 James N. Collins Abstract Using Tagalog as a case study, this paper provides an analysis of a cross-linguistically well attested phenomenon, namely, cases in which a bare NP’s syntactic position is linked to its interpretation as definite or indefinite. Previous approaches to this phenomenon, including analyses of Tagalog, appeal to specialized interpretational rules, such as Diesing’s Mapping Hypothesis. I argue that the patterns fall out of general compositional principles so long as type-shifting operators are available to the gram- matical system. I begin by weighing in a long-standing issue for the semantic analysis of Tagalog: the interpretational distinction between genitive and nominative transitive patients. I show that bare NP patients are interpreted as definites if marked with nominative case and as narrow scope indefinites if marked with genitive case. Bare NPs are understood as basically predicative; their quantificational force is determined by their syntactic position. If they are syntactically local to the selecting verb, they are existentially quantified by the verb itself. If they occupy a derived position, such as the subject position, they must type-shift in order to avoid a type-mismatch, generating a definite interpretation. Thus the paper develops a theory of how the position of an NP is linked to its interpretation, as well as providing a compositional treatment of NP-interpretation in a language which lacks definite articles but demonstrates other morphosyntactic strategies for signaling (in)definiteness. 1 Introduction Not every language signals definiteness via articles. Several languages (such as Russian, Kazakh, Korean etc.) lack articles altogether. -

Logophoricity in Finnish

Open Linguistics 2018; 4: 630–656 Research Article Elsi Kaiser* Effects of perspective-taking on pronominal reference to humans and animals: Logophoricity in Finnish https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2018-0031 Received December 19, 2017; accepted August 28, 2018 Abstract: This paper investigates the logophoric pronoun system of Finnish, with a focus on reference to animals, to further our understanding of the linguistic representation of non-human animals, how perspective-taking is signaled linguistically, and how this relates to features such as [+/-HUMAN]. In contexts where animals are grammatically [-HUMAN] but conceptualized as the perspectival center (whose thoughts, speech or mental state is being reported), can they be referred to with logophoric pronouns? Colloquial Finnish is claimed to have a logophoric pronoun which has the same form as the human-referring pronoun of standard Finnish, hän (she/he). This allows us to test whether a pronoun that may at first blush seem featurally specified to seek [+HUMAN] referents can be used for [-HUMAN] referents when they are logophoric. I used corpus data to compare the claim that hän is logophoric in both standard and colloquial Finnish vs. the claim that the two registers have different logophoric systems. I argue for a unified system where hän is logophoric in both registers, and moreover can be used for logophoric [-HUMAN] referents in both colloquial and standard Finnish. Thus, on its logophoric use, hän does not require its referent to be [+HUMAN]. Keywords: Finnish, logophoric pronouns, logophoricity, anti-logophoricity, animacy, non-human animals, perspective-taking, corpus 1 Introduction A key aspect of being human is our ability to think and reason about our own mental states as well as those of others, and to recognize that others’ perspectives, knowledge or mental states are distinct from our own, an ability known as Theory of Mind (term due to Premack & Woodruff 1978). -

Veridicality and Utterance Meaning

2011 Fifth IEEE International Conference on Semantic Computing Veridicality and utterance understanding Marie-Catherine de Marneffe, Christopher D. Manning and Christopher Potts Linguistics Department Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305 {mcdm,manning,cgpotts}@stanford.edu Abstract—Natural language understanding depends heavily on making the requisite inferences. The inherent uncertainty of assessing veridicality – whether the speaker intends to convey that pragmatic inference suggests to us that veridicality judgments events mentioned are actual, non-actual, or uncertain. However, are not always categorical, and thus are better modeled as this property is little used in relation and event extraction systems, and the work that has been done has generally assumed distributions. We therefore treat veridicality as a distribution- that it can be captured by lexical semantic properties. Here, prediction task. We trained a maximum entropy classifier on we show that context and world knowledge play a significant our annotations to assign event veridicality distributions. Our role in shaping veridicality. We extend the FactBank corpus, features include not only lexical items like hedges, modals, which contains semantically driven veridicality annotations, with and negations, but also structural features and approximations pragmatically informed ones. Our annotations are more complex than the lexical assumption predicts but systematic enough to of world knowledge. The resulting model yields insights into be included in computational work on textual understanding. the complex pragmatic factors that shape readers’ veridicality They also indicate that veridicality judgments are not always judgments. categorical, and should therefore be modeled as distributions. We build a classifier to automatically assign event veridicality II. CORPUS ANNOTATION distributions based on our new annotations. -

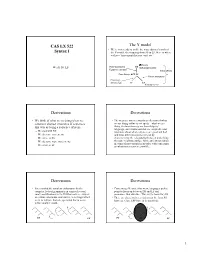

CAS LX 522 Syntax I the Y Model

CAS LX 522 The Y model • We’re now ready to tackle the most abstract branch of Syntax I the Y-model, the mapping from SS to LF. Here is where we have “movement that you can’t see”. θ Theory Week 10. LF Overt movement, DS Subcategorization Expletive insertion X-bar theory Case theory, EPP SS Covert movement Phonology/ Morphology PF LF Binding theory Derivations Derivations • We think of what we’re doing when we • The steps are not necessarily a reflection of what construct abstract structures of sentences we are doing online as we speak—what we are this way as being a sequence of steps. doing is characterizing our knowledge of language, and it turns out that we can predict our – We start with DS intuitions about what sentences are good and bad – We do some movements and what different sentences mean by – We arrive at SS characterizing the relationship between underlying – We do some more movements thematic relations, surface form, and interpretation in terms of movements in an order with constraints – We arrive at LF on what movements are possible. Derivations Derivations • It seems that the simplest explanation for the • Concerning SS, under this view, languages pick a complex facts of grammar is in terms of several point to focus on between DS and LF and small modifications to the DS that each are subject pronounce that structure. This is (the basis for) SS. to certain constraints, sometimes even things which • There are also certain restrictions on the form SS seem to indicate that one operation has to occur has (e.g., Case, EPP have to be satisfied). -

Minimal Pronouns, Logophoricity and Long-Distance Reflexivisation in Avar

Minimal pronouns, logophoricity and long-distance reflexivisation in Avar* Pavel Rudnev Revised version; 28th January 2015 Abstract This paper discusses two morphologically related anaphoric pronouns inAvar (Avar-Andic, Nakh-Daghestanian) and proposes that one of them should be treated as a minimal pronoun that receives its interpretation from a λ-operator situated on a phasal head whereas the other is a logophoric pro- noun denoting the author of the reported event. Keywords: reflexivity, logophoricity, binding, syntax, semantics, Avar 1 Introduction This paper has two aims. One is to make a descriptive contribution to the crosslin- guistic study of long-distance anaphoric dependencies by presenting an overview of the properties of two kinds of reflexive pronoun in Avar, a Nakh-Daghestanian language spoken natively by about 700,000 people mostly living in the North East Caucasian republic of Daghestan in the Russian Federation. The other goal is to highlight the relevance of the newly introduced data from an understudied lan- guage to the theoretical debate on the nature of reflexivity, long-distance anaphora and logophoricity. The issue at the heart of this paper is the unusual character of theanaphoric system in Avar, which is tripartite. (1) is intended as just a preview with more *The present material was presented at the Utrecht workshop The World of Reflexives in August 2011. I am grateful to the workshop’s audience and participants for their questions and comments. I am indebted to Eric Reuland and an anonymous reviewer for providing valuable feedback on the first draft, as well as to Yakov Testelets for numerous discussions of anaphora-related issues inAvar spanning several years. -

Definiteness and Determinacy

Linguistics and Philosophy manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) Definiteness and Determinacy Elizabeth Coppock · David Beaver the date of receipt and acceptance should be inserted later Abstract This paper distinguishes between definiteness and determinacy. Defi- niteness is seen as a morphological category which, in English, marks a (weak) uniqueness presupposition, while determinacy consists in denoting an individual. Definite descriptions are argued to be fundamentally predicative, presupposing uniqueness but not existence, and to acquire existential import through general type-shifting operations that apply not only to definites, but also indefinites and possessives. Through these shifts, argumental definite descriptions may become either determinate (and thus denote an individual) or indeterminate (functioning as an existential quantifier). The latter option is observed in examples like `Anna didn't give the only invited talk at the conference', which, on its indeterminate reading, implies that there is nothing in the extension of `only invited talk at the conference'. The paper also offers a resolution of the issue of whether posses- sives are inherently indefinite or definite, suggesting that, like indefinites, they do not mark definiteness lexically, but like definites, they typically yield determinate readings due to a general preference for the shifting operation that produces them. Keywords definiteness · descriptions · possessives · predicates · type-shifting We thank Dag Haug, Reinhard Muskens, Luca Crniˇc,Cleo Condoravdi, Lucas -

8. Binding Theory

THE COMPLICATED AND MURKY WORLD OF BINDING THEORY We’re about to get sucked into a black hole … 11-13 March Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 2 OUR ROADMAP •Overview of Basic Binding Theory •Binding and Infinitives •Some cross-linguistic comparisons: Icelandic, Ewe, and Logophors •Picture NPs •Binding and Movement: The Nixon Sentences 3 SOME TERMINOLOGY • R-expression: A DP that gets its meaning by referring to an entity in the world. • Anaphor: A DP that obligatorily gets its meaning from another DP in the sentence. 1. Heidi bopped herself on the head with a zucchini. [Carnie 2013: Ch. 5, EX 3] • Reflexives: Myself, Yourself, Herself, Himself, Itself, Ourselves, Yourselves, Themselves • Reciprocals: Each Other, One Another • Pronoun: A DP that may get its meaning from another DP in the sentence or contextually, from the discourse. 2. Art said that he played basketball. [EX5] • “He” could be Art or someone else. • I/Me, You/You, She/Her, He/Him, It/It, We/Us, You/You, They/Them • Nominative/Accusative Pronoun Pairs in English • Antecedent: A DP that gives its meaning to another DP. • This is familiar from control; PRO needs an antecedent. Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 4 OBSERVATION 1: NO NOMINATIVE FORMS OF ANAPHORS • This makes sense, since anaphors cannot be subjects of finite clauses. 1. * Sheselfi / Herselfi bopped Heidii on the head with a zucchini. • Anaphors can be the subjects of ECM clauses. 2. Heidi believes herself to be an excellent cook, even though she always bops herself on the head with zucchini. SOME DESCRIPTIVE OBSERVATIONS Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. -

Martian Crater Morphology

ANALYSIS OF THE DEPTH-DIAMETER RELATIONSHIP OF MARTIAN CRATERS A Capstone Experience Thesis Presented by Jared Howenstine Completion Date: May 2006 Approved By: Professor M. Darby Dyar, Astronomy Professor Christopher Condit, Geology Professor Judith Young, Astronomy Abstract Title: Analysis of the Depth-Diameter Relationship of Martian Craters Author: Jared Howenstine, Astronomy Approved By: Judith Young, Astronomy Approved By: M. Darby Dyar, Astronomy Approved By: Christopher Condit, Geology CE Type: Departmental Honors Project Using a gridded version of maritan topography with the computer program Gridview, this project studied the depth-diameter relationship of martian impact craters. The work encompasses 361 profiles of impacts with diameters larger than 15 kilometers and is a continuation of work that was started at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston, Texas under the guidance of Dr. Walter S. Keifer. Using the most ‘pristine,’ or deepest craters in the data a depth-diameter relationship was determined: d = 0.610D 0.327 , where d is the depth of the crater and D is the diameter of the crater, both in kilometers. This relationship can then be used to estimate the theoretical depth of any impact radius, and therefore can be used to estimate the pristine shape of the crater. With a depth-diameter ratio for a particular crater, the measured depth can then be compared to this theoretical value and an estimate of the amount of material within the crater, or fill, can then be calculated. The data includes 140 named impact craters, 3 basins, and 218 other impacts. The named data encompasses all named impact structures of greater than 100 kilometers in diameter. -

QUALM; *Quoion Answeringsystems

DOCUMENT RESUME'. ED 150 955 IR 005 492 AUTHOR Lehnert, Wendy TITLE The Process'of Question Answering. Research Report No. 88. ..t. SPONS AGENCY Advanced Research Projects Agency (DOD), Washington, D.C. _ PUB DATE May 77 CONTRACT ,N00014-75-C-1111 . ° NOTE, 293p.;- Ph.D. Dissertation, Yale University 'ERRS' PRICE NF -$0.83 1C- $15.39 Plus Post'age. DESCRIPTORS .*Computer Programs; Computers; *'conceptual Schemes; *Information Processing; *Language Classification; *Models; Prpgrai Descriptions IDENTIFIERS *QUALM; *QuOion AnsweringSystems . \ ABSTRACT / The cOmputationAl model of question answering proposed by a.lamputer program,,QUALM, is a theory of conceptual information processing based 'bon models of, human memory organization. It has been developed from the perspective of' natural language processing in conjunction with story understanding systems. The p,ocesses in QUALM are divided into four phases:(1) conceptual categorization; (2) inferential analysis;(3) content specification; and (4) 'retrieval heuristict. QUALM providea concrete criterion for judging the strengths and weaknesses'of store representations.As a theoretical model, QUALM is intended to describ general question answerinlg, where question antiering is viewed as aerbal communicb.tion. device betieen people.(Author/KP) A. 1 *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied'by EDRS are the best that can be made' * from. the original document. ********f******************************************,******************* 1, This work-was -

A Syntactic Analysis of Rhetorical Questions

A Syntactic Analysis of Rhetorical Questions Asier Alcázar 1. Introduction* A rhetorical question (RQ: 1b) is viewed as a pragmatic reading of a genuine question (GQ: 1a). (1) a. Who helped John? [Mary, Peter, his mother, his brother, a neighbor, the police…] b. Who helped John? [Speaker follows up: “Well, me, of course…who else?”] Rohde (2006) and Caponigro & Sprouse (2007) view RQs as interrogatives biased in their answer set (1a = unbiased interrogative; 1b = biased interrogative). In unbiased interrogatives, the probability distribution of the answers is even.1 The answer in RQs is biased because it belongs in the Common Ground (CG, Stalnaker 1978), a set of mutual or common beliefs shared by speaker and addressee. The difference between RQs and GQs is thus pragmatic. Let us refer to these approaches as Option A. Sadock (1971, 1974) and Han (2002), by contrast, analyze RQs as no longer interrogative, but rather as assertions of opposite polarity (2a = 2b). Accordingly, RQs are not defined in terms of the properties of their answer set. The CG is not invoked. Let us call these analyses Option B. (2) a. Speaker says: “I did not lie.” b. Speaker says: “Did I lie?” [Speaker follows up: “No! I didn’t!”] For Han (2002: 222) RQs point to a pragmatic interface: “The representation at this level is not LF, which is the output of syntax, but more abstract than that. It is the output of further post-LF derivation via interaction with at least a sub part of the interpretational component, namely pragmatics.” RQs are not seen as syntactic objects, but rather as a post-syntactic interface phenomenon.