From the Editor JCSSS 7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monuments, Materiality, and Meaning in the Classical Archaeology of Anatolia

MONUMENTS, MATERIALITY, AND MEANING IN THE CLASSICAL ARCHAEOLOGY OF ANATOLIA by Daniel David Shoup A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Art and Archaeology) in The University of Michigan 2008 Doctoral Committee: Professor Elaine K. Gazda, Co-Chair Professor John F. Cherry, Co-Chair, Brown University Professor Fatma Müge Göçek Professor Christopher John Ratté Professor Norman Yoffee Acknowledgments Athena may have sprung from Zeus’ brow alone, but dissertations never have a solitary birth: especially this one, which is largely made up of the voices of others. I have been fortunate to have the support of many friends, colleagues, and mentors, whose ideas and suggestions have fundamentally shaped this work. I would also like to thank the dozens of people who agreed to be interviewed, whose ideas and voices animate this text and the sites where they work. I offer this dissertation in hope that it contributes, in some small way, to a bright future for archaeology in Turkey. My committee members have been unstinting in their support of what has proved to be an unconventional project. John Cherry’s able teaching and broad perspective on archaeology formed the matrix in which the ideas for this dissertation grew; Elaine Gazda’s support, guidance, and advocacy of the project was indispensible to its completion. Norman Yoffee provided ideas and support from the first draft of a very different prospectus – including very necessary encouragement to go out on a limb. Chris Ratté has been a generous host at the site of Aphrodisias and helpful commentator during the writing process. -

Power, Politics, and Tradition in the Mongol Empire and the Ilkhanate of Iran

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi POWER, POLITICS, AND TRADITION IN THE MONGOL EMPIRE AND THE ĪlkhānaTE OF IRAN OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi Power, Politics, and Tradition in the Mongol Empire and the Īlkhānate of Iran MICHAEL HOPE 1 OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6D P, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Michael Hope 2016 The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in 2016 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: 2016932271 ISBN 978–0–19–876859–3 Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

The Latin Principality of Antioch and Its Relationship with the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, 1188-1268 Samuel James Wilson

The Latin Principality of Antioch and Its Relationship with the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, 1188-1268 Samuel James Wilson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Nottingham Trent University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2016 1 Copyright Statement This work is the intellectual property of the author. You may copy up to 5% of this work for private study, or personal, non-commercial research. Any re-use of the information contained within this document should be fully referenced, quoting the author, title, university, degree level and pagination. Queries or requests for any other use, or if a more substantial copy is required, should be directed to the owner of the Intellectual Property Rights. 2 Abstract The Latin principality of Antioch was founded during the First Crusade (1095-1099), and survived for 170 years until its destruction by the Mamluks in 1268. This thesis offers the first full assessment of the thirteenth century principality of Antioch since the publication of Claude Cahen’s La Syrie du nord à l’époque des croisades et la principauté franque d’Antioche in 1940. It examines the Latin principality from its devastation by Saladin in 1188 until the fall of Antioch eighty years later, with a particular focus on its relationship with the Armenian kingdom of Cilicia. This thesis shows how the fate of the two states was closely intertwined for much of this period. The failure of the principality to recover from the major territorial losses it suffered in 1188 can be partly explained by the threat posed by the Cilician Armenians in the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries. -

Practicing Love of God in Medieval Jerusalem, Gaul and Saxony

he collection of essays presented in “Devotional Cross-Roads: Practicing Love of God in Medieval Gaul, Jerusalem, and Saxony” investigates test case witnesses of TChristian devotion and patronage from Late Antiquity to the Late Middle Ages, set in and between the Eastern and Western Mediterranean, as well as Gaul and the regions north of the Alps. Devotional practice and love of God refer to people – mostly from the lay and religious elite –, ideas, copies of texts, images, and material objects, such as relics and reliquaries. The wide geographic borders and time span are used here to illustrate a broad picture composed around questions of worship, identity, reli- gious affiliation and gender. Among the diversity of cases, the studies presented in this volume exemplify recurring themes, which occupied the Christian believer, such as the veneration of the Cross, translation of architecture, pilgrimage and patronage, emergence of iconography and devotional patterns. These essays are representing the research results of the project “Practicing Love of God: Comparing Women’s and Men’s Practice in Medieval Saxony” guided by the art historian Galit Noga-Banai, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and the histori- an Hedwig Röckelein, Georg-August-University Göttingen. This project was running from 2013 to 2018 within the Niedersachsen-Israeli Program and financed by the State of Lower Saxony. Devotional Cross-Roads Practicing Love of God in Medieval Jerusalem, Gaul and Saxony Edited by Hedwig Röckelein, Galit Noga-Banai, and Lotem Pinchover Röckelein/Noga-Banai/Pinchover Devotional Cross-Roads ISBN 978-3-86395-372-0 Universitätsverlag Göttingen Universitätsverlag Göttingen Hedwig Röckelein, Galit Noga-Banai, and Lotem Pinchover (Eds.) Devotional Cross-Roads This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. -

![Cilician Armenia in the Thirteenth Century.[3] Marco Polo, for Example, Set out on His Journey to China from Ayas in 1271](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9192/cilician-armenia-in-the-thirteenth-century-3-marco-polo-for-example-set-out-on-his-journey-to-china-from-ayas-in-1271-1709192.webp)

Cilician Armenia in the Thirteenth Century.[3] Marco Polo, for Example, Set out on His Journey to China from Ayas in 1271

The Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia (also known as Little Armenia; not to be confused with the Arme- nian Kingdom of Antiquity) was a state formed in the Middle Ages by Armenian refugees fleeing the Seljuk invasion of Armenia. It was located on the Gulf of Alexandretta of the Mediterranean Sea in what is today southern Turkey. The kingdom remained independent from around 1078 to 1375. The Kingdom of Cilicia was founded by the Rubenian dynasty, an offshoot of the larger Bagratid family that at various times held the thrones of Armenia and Georgia. Their capital was Sis. Cilicia was a strong ally of the European Crusaders, and saw itself as a bastion of Christendom in the East. It also served as a focus for Armenian nationalism and culture, since Armenia was under foreign oc- cupation at the time. King Levon I of Armenia helped cultivate Cilicia's economy and commerce as its interaction with European traders grew. Major cities and castles of the kingdom included the port of Korikos, Lam- pron, Partzerpert, Vahka (modern Feke), Hromkla, Tarsus, Anazarbe, Til Hamdoun, Mamistra (modern Misis: the classical Mopsuestia), Adana and the port of Ayas (Aias) which served as a Western terminal to the East. The Pisans, Genoese and Venetians established colonies in Ayas through treaties with Cilician Armenia in the thirteenth century.[3] Marco Polo, for example, set out on his journey to China from Ayas in 1271. For a short time in the 1st century BCE the powerful kingdom of Armenia was able to conquer a vast region in the Levant, including the area of Cilicia. -

Cilician Armenian Mediation in Crusader-Mongol Politics, C.1250-1350

HAYTON OF KORYKOS AND LA FLOR DES ESTOIRES: CILICIAN ARMENIAN MEDIATION IN CRUSADER-MONGOL POLITICS, C.1250-1350 by Roubina Shnorhokian A thesis submitted to the Department of History In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (January, 2015) Copyright ©Roubina Shnorhokian, 2015 Abstract Hayton’s La Flor des estoires de la terre d’Orient (1307) is typically viewed by scholars as a propagandistic piece of literature, which focuses on promoting the Ilkhanid Mongols as suitable allies for a western crusade. Written at the court of Pope Clement V in Poitiers in 1307, Hayton, a Cilician Armenian prince and diplomat, was well-versed in the diplomatic exchanges between the papacy and the Ilkhanate. This dissertation will explore his complex interests in Avignon, where he served as a political and cultural intermediary, using historical narrative, geography and military expertise to persuade and inform his Latin audience of the advantages of allying with the Mongols and sending aid to Cilician Armenia. This study will pay close attention to the ways in which his worldview as a Cilician Armenian informed his perceptions. By looking at a variety of sources from Armenian, Latin, Eastern Christian, and Arab traditions, this study will show that his knowledge was drawn extensively from his inter-cultural exchanges within the Mongol Empire and Cilician Armenia’s position as a medieval crossroads. The study of his career reflects the range of contacts of the Eurasian world. ii Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without the financial support of SSHRC, the Marjorie McLean Oliver Graduate Scholarship, OGS, and Queen’s University. -

Local Cults and Their Integration Into Bethlehem's Sacred Landscape In

1 Local Cults and Their Integration into Bethlehem’s Sacred Landscape in the Late Medieval and Modern Periods1 Michele Bacci (University of Fribourg, Switzerland) Bethlehem has been a goal for pilgrims since the very beginnings of Christian pil- grimage and its memorial meanings as birthplace of Jesus are so universally acknowledged that, paradoxically enough, it is much easier to evaluate it as a global phenomenon than to understand it in its local context. The symbolic efficacy of the holy cave was enhanced by its magnificent architectural frame, its specific mise-en- scène, and the ritualized approach to it organized by its clerical custodians.2 As elsewhere in the Holy Land, worship was addressed to a cult-object that, in strik- ing contrast with the believers’ habits in their home countries, was not a body relic or a miraculous image, but rather a portion of ground deemed to bear witness to scriptural events and, at least to some extent, to have been hallowed by contact with Christ’s body. As every cult-object, it could be worshipped also in its copies, which could be diminutive and portable as the wooden and mother-of-pearl mod- els of the holy cave created, in the 17th and 18th centuries, in the Bethlehem workshops: such replicas, as the one preserved in the Dominican nunnery of Santo Domingo el Antiguo in Toledo, Spain (Fig. 1), disseminated knowledge of the holy site’s materiality throughout Europe and were perhaps the most important contri- bution of local artists to the shaping of their town’s global renown.3 But for the rest, we are admittedly very scarcely informed about the ways in which the auratic power associated with the holy site, whose experience is described in countless pilgrims’ travelogues from almost all corners of the world, made an impact on local religious life and everyday habits in the Middle Ages and the Modern era. -

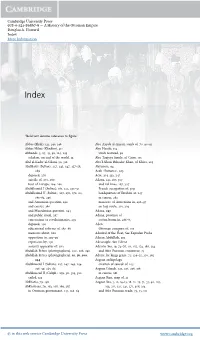

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89867-6 — a History of the Ottoman Empire Douglas A

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89867-6 — A History of the Ottoman Empire Douglas A. Howard Index More Information Index “Bold text denotes reference to figure” Abbas (Shah), 121, 140, 148 Abu Ayyub al-Ansari, tomb of, 70, 90–91 Abbas Hilmi (Khedive), 311 Abu Hanifa, 114 Abbasids, 3, 27, 45, 92, 124, 149 tomb restored, 92 scholars, on end of the world, 53 Abu Taqiyya family, of Cairo, 155 Abd al-Kader al-Gilani, 92, 316 Abu’l-Ghazi Bahadur Khan, of Khiva, 265 Abdülaziz (Sultan), 227, 245, 247, 257–58, Abyssinia, 94 289 Aceh (Sumatra), 203 deposed, 270 Acre, 214, 233, 247 suicide of, 270, 280 Adana, 141, 287, 307 tour of Europe, 264, 266 and rail lines, 287, 307 Abdülhamid I (Sultan), 181, 222, 230–31 French occupation of, 309 Abdülhamid II (Sultan), 227, 270, 278–80, headquarters of Ibrahim at, 247 283–84, 296 in census, 282 and Armenian question, 292 massacre of Armenians in, 296–97 and census, 280 on hajj route, 201, 203 and Macedonian question, 294 Adana, 297 and public ritual, 287 Adana, province of concessions to revolutionaries, 295 cotton boom in, 286–87 deposed, 296 Aden educational reforms of, 287–88 Ottoman conquest of, 105 memoirs about, 280 Admiral of the Fleet, See Kapudan Pasha opposition to, 292–93 Adnan Abdülhak, 319 repression by, 292 Adrianople. See Edirne security apparatus of, 280 Adriatic Sea, 19, 74–76, 111, 155, 174, 186, 234 Abdullah Frères (photographers), 200, 288, 290 and Afro-Eurasian commerce, 74 Abdullah Frères (photographers), 10, 56, 200, Advice for kings genre, 71, 124–25, 150, 262 244 Aegean archipelago -

7Western Europe and Byzantium

Western Europe and Byzantium circa 500 - 1000 CE 7Andrew Reeves 7.1 CHRONOLOGY 410 CE Roman army abandons Britain 476 CE The general Odavacar deposes last Western Roman Emperor 496 CE The Frankish king Clovis converts to Christianity 500s CE Anglo-Saxons gradually take over Britain 533 CE Byzantine Empire conquers the Vandal kingdom in North Africa 535 – 554 CE Byzantine Empire conquers the Ostrogothic kingdom in Italy 560s CE Lombard invasions of Italy begin 580s CE The Franks cease keeping tax registers 597 CE Christian missionaries dispatched from Rome arrive in Britain 610 – 641 CE Heraclius is Byzantine emperor 636 CE Arab Muslims defeat the Byzantine army at the Battle of Yarmouk 670s CE Byzantine Empire begins to lose control of the Balkans to Avars, Bulgars, and Slavs 674 – 678 CE Arabs lay siege to Constantinople but are unsuccessful 711 CE Muslims from North Africa conquer Spain, end of the Visigothic kingdom 717 – 718 CE Arabs lay siege to Constantinople but are unsuccessful 717 CE Leo III becomes Byzantine emperor. Under his rule, the Iconoclast Controversy begins. 732 CE King Charles Martel of the Franks defeats a Muslim invasion of the kingdom at the Battle of Tours 751 CE The Byzantine city of Ravenna falls to the Lombards; Pepin the Short of the Franks deposes the last Merovingian king and becomes king of the Franks; King Pepin will later conquer Central Italy and donate it to the pope 750s CE Duke of Naples ceases to acknowledge the authority of the Byzantine emperor 770s CE Effective control of the city of Rome passes from Byzantium to the papacy c. -

History of the Crusades. Episode 100 Baibars. Wait, Did I Just Say Episode

History of the Crusades. Episode 100 Baibars. Wait, did I just say Episode 100? Woohoo! Wow, that seemed to go quickly. Even though there's clearly cause to celebrate, we have a lot to get through in this episode, so put the cork back in champagne bottles and we'd better press forward. So where am I? Here we go. Hello again. Last week we saw the Egyptian Mamluks defeat the Mongols in the Battle of Ain Jalut. Now it's hard to overstate the historical importance of this battle. The Egyptians were victorious, and their victory meant that the Mongol invasion was driven back, with its western borders now lying in Persia. Egypt then occupied all of Syria, and the Egyptian Mamluks went on to establish a power-base which would see them prevail as the dominant Muslim force in the Middle East until the rise of the Ottoman Empire in the 1400s. What would have happened if the Mongols won the Battle of Ain Jalut? Well, it's difficult to speculate, but Steven Runciman, in the third book of his trilogy on the Crusades, states that had the Mongols won the Battle of Ain Jalut, they no doubt would have pressed their advantage and gone on to conquer Egypt, meaning there would have been no great Muslim power remaining in the Middle East. The closest Muslim country would have been Morocco, far to the west in North Africa. Kitbuqa, the Mongol commander defeated at Ain Jalut, was a Nestorian Christian. Had he prevailed in battle, it's likely that the native Christians in the Middle East may have for the first time, risen to power under the Mongols. -

14. Yüzyil Alman Hacilarin Seyahatnamelerġnde Rodos Ve Çevresġ

ABAD / JABS ANADOLU VE BALKAN ARAŞTIRMALARI DERGİSİ JOURNAL OF ANATOLIA AND BALKAN STUDIES ABAD, 2021; 4(7): 3-16 [email protected] ISSN: 2618-6004 DOI: 10.32953/abad.795517 e-ISSN: 2636-8188 14. YÜZYIL ALMAN HACILARIN SEYAHATNAMELERĠNDE RODOS VE ÇEVRESĠ Zeynep ĠNAN ALĠYAZICIOĞLU Öz: Erken Orta Çağ’dan itibaren Kudüs, Avrupalı Hristiyanlar için önemli bir hac merkeziydi. 14. yüzyılda dört Alman hacı seyyah Kudüs’e gidişleri ve memleketlerine dönüşleri sırasında başta Rodos ve Girit olmak üzere çeşitli Ege adalarında bulunmuşlardır. Wilhelm von Boldensele 1335’te Kudüs’e giderken Ege sahillerini, Girit, Rodos ve Kıbrıs adalarını ziyaret ederek bölge hakkında kısa betimlemeler kaleme almıştır. Aynı tarihte Alman hacı seyyah Ludolf von Sudheim da Boldensele’nin hac güzergahı üzerinden Kutsal Topraklara varmıştır. Sudheim, eserinde Rodos ve çevresine dair daha detaylı malumat vermiştir. 1385 yılında Lorenz Egen ve Peter Sparnau Kudüs’ten Avrupa’ya dönüş yolunda Rodos’u ziyaret etmiş ve Anadolu’nun Ege kıyısı boyunca ilerleyerek Bizans başkentine varmıştır. Mezkûr hacılar Rodos ve çevresine dair dönemin siyasi yapısı, bölgedeki halkın günlük yaşamı, nüfusu, dini yapısı ve Rodos 3 adasının savunması, stratejik durumu hakkında okuyucuya bilgi vermiştir. Bu çalışmada 14. yüzyılda Alman seyyahların hac güzergahlarında uğradıkları Rodos Adası ve çevresine dair seyahatnamelerinde verdikleri betimlemeler incelenmeye çalışılmıştır. Anahtar Kelimeler: Rodos, Boldensele, Sudheim, Lorenz Egen, Peter Sparnau. RHODES AND ITS ENVIRONETMENT IN THE TRAVEL REPORT OF THE 14TH CENTURY GERMAN PILGRIMS Abstract: Since the early Middle Ages, Jerusalem was an important pilgrimage center for European Christians. In the 14th century, four German pilgrims visited various Aegean islands, mainly Rhodes and Crete, while on their way to Jerusalem and while returning to Europe. -

Michele Bacci

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by RERO DOC Digital Library Michele Bacci A SACRED SPACE FOR A HOLY ICON: THE SHRINE OF OUR LADY OF SAYDNAYA In fourteenth-century Florence, only a small percentage of the people had the heart (and the money) to embark on a voyage to the Holy Land for the remission of one’s own sins. Those who stayed at home, however, had the chance to visit the loca sancta by virtue of a mental and spiritual exercise whose characteristics are unveiled to us by a still extant prayer in vernacular Italian: the title explains that “herewith are the voyages which are taken by those pilgrims going overseas for their souls’ sake and which can even be taken by anybody staying at home and thinking of each place described herewith, by saying each time a Paternoster and an Ave Maria”. Such an imaginary pilgrimage included not only the most holy places of Jerusalem and Palestine, where Our Lord lived and performed his miracles, but also other shrines being unrelated to Biblical or Evangelic topography; in this respect, a special passage within the prayer deserves to be quoted: Then, you will go to Mount Sinai, and will find the tomb of Saint Catherine and her body whence oil gushes out. And you will also find a vase which the Virgin Mary put there with her own hands. Then you will go to Babylon, and will find a fountain, where the angel washed the clothes of our Lord, and hung the washing out to dry on a tree, and from that tree comes out the balm by the grace of God.