Michele Bacci

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Potential for an Assad Statelet in Syria

THE POTENTIAL FOR AN ASSAD STATELET IN SYRIA Nicholas A. Heras THE POTENTIAL FOR AN ASSAD STATELET IN SYRIA Nicholas A. Heras policy focus 132 | december 2013 the washington institute for near east policy www.washingtoninstitute.org The opinions expressed in this Policy Focus are those of the author and not necessar- ily those of The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, its Board of Trustees, or its Board of Advisors. MAPS Fig. 1 based on map designed by W.D. Langeraar of Michael Moran & Associates that incorporates data from National Geographic, Esri, DeLorme, NAVTEQ, UNEP- WCMC, USGS, NASA, ESA, METI, NRCAN, GEBCO, NOAA, and iPC. Figs. 2, 3, and 4: detail from The Tourist Atlas of Syria, Syria Ministry of Tourism, Directorate of Tourist Relations, Damascus. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publica- tion may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2013 by The Washington Institute for Near East Policy The Washington Institute for Near East Policy 1828 L Street NW, Suite 1050 Washington, DC 20036 Cover: Digitally rendered montage incorporating an interior photo of the tomb of Hafez al-Assad and a partial view of the wheel tapestry found in the Sheikh Daher Shrine—a 500-year-old Alawite place of worship situated in an ancient grove of wild oak; both are situated in al-Qurdaha, Syria. Photographs by Andrew Tabler/TWI; design and montage by 1000colors. -

Monuments, Materiality, and Meaning in the Classical Archaeology of Anatolia

MONUMENTS, MATERIALITY, AND MEANING IN THE CLASSICAL ARCHAEOLOGY OF ANATOLIA by Daniel David Shoup A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Art and Archaeology) in The University of Michigan 2008 Doctoral Committee: Professor Elaine K. Gazda, Co-Chair Professor John F. Cherry, Co-Chair, Brown University Professor Fatma Müge Göçek Professor Christopher John Ratté Professor Norman Yoffee Acknowledgments Athena may have sprung from Zeus’ brow alone, but dissertations never have a solitary birth: especially this one, which is largely made up of the voices of others. I have been fortunate to have the support of many friends, colleagues, and mentors, whose ideas and suggestions have fundamentally shaped this work. I would also like to thank the dozens of people who agreed to be interviewed, whose ideas and voices animate this text and the sites where they work. I offer this dissertation in hope that it contributes, in some small way, to a bright future for archaeology in Turkey. My committee members have been unstinting in their support of what has proved to be an unconventional project. John Cherry’s able teaching and broad perspective on archaeology formed the matrix in which the ideas for this dissertation grew; Elaine Gazda’s support, guidance, and advocacy of the project was indispensible to its completion. Norman Yoffee provided ideas and support from the first draft of a very different prospectus – including very necessary encouragement to go out on a limb. Chris Ratté has been a generous host at the site of Aphrodisias and helpful commentator during the writing process. -

Syrian Armed Opposition Powerbrokers

March 2016 Jennifer Cafarella and Genevieve Casagrande MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 29 SYRIAN ARMED OPPOSITION POWERBROKERS Cover: A rebel fighter of the Southern Front of the Free Syrian Army gestures while standing with his fellow fighter near their weapons at the front line in the north-west countryside of Deraa March 3, 2015. Syrian government forces have taken control of villages in southern Syria, state media said on Saturday, part of a campaign they started this month against insurgents posing one of the biggest remaining threats to Damascus. Picture taken March 3, 2015. REUTERS/Stringer All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ©2016 by the Institute for the Study of War. Published in 2016 in the United States of America by the Institute for the Study of War. 1400 16th Street NW, Suite 515 | Washington, DC 20036 www.understandingwar.org Jennifer Cafarella and Genevieve Casagrande MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 29 SYRIAN ARMED OPPOSITION POWERBROKERS ABOUT THE AUTHORS Jennifer Cafarella is the Evans Hanson Fellow at the Institute for the Study of War where she focuses on the Syrian Civil War and opposition groups. Her research focuses particularly on the al Qaeda affiliate Jabhat al Nusra and their military capabilities, modes of governance, and long-term strategic vision. She is the author of Likely Courses of Action in the Syrian Civil War: June-December 2015, and Jabhat al-Nusra in Syria: An Islamic Emirate for al-Qaeda. -

The Syrian Orthodox Church and Its Ancient Aramaic Heritage, I-Iii (Rome, 2001)

Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies 5:1, 63-112 © 2002 by Beth Mardutho: The Syriac Institute SOME BASIC ANNOTATION TO THE HIDDEN PEARL: THE SYRIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH AND ITS ANCIENT ARAMAIC HERITAGE, I-III (ROME, 2001) SEBASTIAN P. BROCK UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD [1] The three volumes, entitled The Hidden Pearl. The Syrian Orthodox Church and its Ancient Aramaic Heritage, published by TransWorld Film Italia in 2001, were commisioned to accompany three documentaries. The connecting thread throughout the three millennia that are covered is the Aramaic language with its various dialects, though the emphasis is always on the users of the language, rather than the language itself. Since the documentaries were commissioned by the Syrian Orthodox community, part of the third volume focuses on developments specific to them, but elsewhere the aim has been to be inclusive, not only of the other Syriac Churches, but also of other communities using Aramaic, both in the past and, to some extent at least, in the present. [2] The volumes were written with a non-specialist audience in mind and so there are no footnotes; since, however, some of the inscriptions and manuscripts etc. which are referred to may not always be readily identifiable to scholars, the opportunity has been taken to benefit from the hospitality of Hugoye in order to provide some basic annotation, in addition to the section “For Further Reading” at the end of each volume. Needless to say, in providing this annotation no attempt has been made to provide a proper 63 64 Sebastian P. Brock bibliography to all the different topics covered; rather, the aim is simply to provide specific references for some of the more obscure items. -

Practicing Love of God in Medieval Jerusalem, Gaul and Saxony

he collection of essays presented in “Devotional Cross-Roads: Practicing Love of God in Medieval Gaul, Jerusalem, and Saxony” investigates test case witnesses of TChristian devotion and patronage from Late Antiquity to the Late Middle Ages, set in and between the Eastern and Western Mediterranean, as well as Gaul and the regions north of the Alps. Devotional practice and love of God refer to people – mostly from the lay and religious elite –, ideas, copies of texts, images, and material objects, such as relics and reliquaries. The wide geographic borders and time span are used here to illustrate a broad picture composed around questions of worship, identity, reli- gious affiliation and gender. Among the diversity of cases, the studies presented in this volume exemplify recurring themes, which occupied the Christian believer, such as the veneration of the Cross, translation of architecture, pilgrimage and patronage, emergence of iconography and devotional patterns. These essays are representing the research results of the project “Practicing Love of God: Comparing Women’s and Men’s Practice in Medieval Saxony” guided by the art historian Galit Noga-Banai, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and the histori- an Hedwig Röckelein, Georg-August-University Göttingen. This project was running from 2013 to 2018 within the Niedersachsen-Israeli Program and financed by the State of Lower Saxony. Devotional Cross-Roads Practicing Love of God in Medieval Jerusalem, Gaul and Saxony Edited by Hedwig Röckelein, Galit Noga-Banai, and Lotem Pinchover Röckelein/Noga-Banai/Pinchover Devotional Cross-Roads ISBN 978-3-86395-372-0 Universitätsverlag Göttingen Universitätsverlag Göttingen Hedwig Röckelein, Galit Noga-Banai, and Lotem Pinchover (Eds.) Devotional Cross-Roads This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. -

Pilgrimage in Syria 8 Days

Pilgrimage in Syria 8 Days Day 1: Arrival Arrival to airport Meet and assist and transfer to Hotel Dinner and overnight Day 2: Saydnaya – Maaloula – Saint George – Krak Saydnaya: It was one of the episcopal cities of the ancient Patriarchate of Antioch. Associated with many Biblical and religious events, local tradition holds it as the site where Cain slew his brother Abel. Pilgrims seek Saidnaya for renewal of faith and for healing. Renowned for its faithfulness to Christianity, tradition holds that the Convent of Our Lady of Saidnaya was constructed by the Byzantine emperor Justinian I in 547 AD, after he had two visions of Mary. Also located in the convent of Saidnaya is an icon of the Holy Mother and Child known as the Shaghurah and reputed to have been painted by Luke the Evangelist which is believed to protect its owners from harm in times of danger. Maaloula: It is the only place where a dialect of the Western branch of the Aramaic language is still spoken. Scholars have determined that the Aramaic of Jesus belonged to this particular branch as well. Maaloula represents, therefore, an important source for anthropological linguistic studies regarding first century Aramaic. There are two important monasteries in Maaloula: Greek Catholic Mar Sarkis and Greek Orthodox Mar Thecla. Mar Sarkis is one of the oldest surviving monasteries in Syria. It was built on the site of a pagan temple, and has elements which go back to the fifth to sixth century Byzantine period. Mar Taqla monastery holds the remains of St. Taqla; daughter of one of Seleucid princes, and pupil of St. -

Pilgrimage in Syria 5 Days

Pilgrimage in Syria 5 Days Day 1: Arrival Arrival to airport Meet and assist and transfer to Hotel Dinner and overnight Day 2: Full day Damascus Damascus is mentioned in Genesis 14:15 as existing at the time of the War of the Kings Nicolaus of Damascus, in the fourth book of his History, says thus: "Abraham reigned at Damascus”. According to the New Testament, Saint Paul was on the road to Damascus when he received a vision of Jesus, and as a result accepted him as the Messiah. The Damascus Straight Street (referred to in the conversion of St. Paul in Acts 9:11), also known as the Via Recta, was the decumanus of Roman Damascus, and extended for over 1,500 meters (4,900 ft). Today, it consists of the street of Bab Sharqi and the Souk Medhat Pasha. The House of Saint Ananias (also called Chapel of Saint Ananias) is the ancient alleged house of Saint Ananias, in the old Christian quarter. It is said by some to be the house where Ananias baptized Saul. The Chapel of Saint Paul is a modern stone chapel in Damascus that incorporates materials from the Bab Kisan, the ancient city gate through which Paul was lowered to escape the jews After began the tireless Christian preaching that would characterize the rest of his life (Acts 9:20-25). Paul himself later says that it was through a window that he escaped from certain death (2 Cor 11:32-33). According to the Acts of the Apostles, Saint Thomas also lived in that neighborhood. -

La Région Du Qalamoun Situation Sécuritaire Et Structuration Des Groupes Armés Rebelles Entre 2013 Et 2015

SYRIE Note 19 mai 2016 La région du Qalamoun Situation sécuritaire et structuration des groupes armés rebelles entre 2013 et 2015 Résumé Point sur la présence de groupes armés rebelles dans la région du Qalamoun et sur leurs exactions, ainsi que sur les principales offensives opérées dans la région entre 2013 et 2015. Abstract Brief snapshot of the armed opposition groups that operate in the Qalamun region and of the abuses they allegedly committed, and overview of the major military operations launched in the region during 2013-2014. Avertissement Ce document a été élaboré par la Division de l’Information, de la Documentation et des Recherches de l’Ofpra en vue de fournir des informations utiles à l’examen des demandes de protection internationale. Il ne prétend pas faire le traitement exhaustif de la problématique, ni apporter de preuves concluantes quant au fondement d’une demande de protection internationale particulière. Il ne doit pas être considéré comme une position officielle de l’Ofpra ou des autorités françaises. Ce document, rédigé conformément aux lignes directrices communes à l’Union européenne pour le traitement de l’information sur le pays d’origine (avril 2008) [cf. https://www.ofpra.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/atoms/files/lignes_directrices_europeennes.pdf ], se veut impartial et se fonde principalement sur des renseignements puisés dans des sources qui sont à la disposition du public. Toutes les sources utilisées sont référencées. Elles ont été sélectionnées avec un souci constant de recouper les informations. Le fait qu’un événement, une personne ou une organisation déterminée ne soit pas mentionné(e) dans la présente production ne préjuge pas de son inexistence. -

Middle East Security Report 29

March 2016 Jennifer Cafarella and Genevieve Casagrande MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 29 SYRIAN ARMED OPPOSITION POWERBROKERS Cover: A rebel fighter of the Southern Front of the Free Syrian Army gestures while standing with his fellow fighter near their weapons at the front line in the north-west countryside of Deraa March 3, 2015. Syrian government forces have taken control of villages in southern Syria, state media said on Saturday, part of a campaign they started this month against insurgents posing one of the biggest remaining threats to Damascus. Picture taken March 3, 2015. REUTERS/Stringer All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ©2016 by the Institute for the Study of War. Published in 2016 in the United States of America by the Institute for the Study of War. 1400 16th Street NW, Suite 515 | Washington, DC 20036 www.understandingwar.org Jennifer Cafarella and Genevieve Casagrande MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 29 SYRIAN ARMED OPPOSITION POWERBROKERS ABOUT THE AUTHORS Jennifer Cafarella is the Evans Hanson Fellow at the Institute for the Study of War where she focuses on the Syrian Civil War and opposition groups. Her research focuses particularly on the al Qaeda affiliate Jabhat al Nusra and their military capabilities, modes of governance, and long-term strategic vision. She is the author of Likely Courses of Action in the Syrian Civil War: June-December 2015, and Jabhat al-Nusra in Syria: An Islamic Emirate for al-Qaeda. -

The View from Here Artists // Public Policy Ceu School of Public Policy Annual Conference June 4 / 5 / 6 / 7 / 2016 Another Day Lost: 1906 and Counting

the view from here artists // public policy ceu school of public policy annual conference june 4 / 5 / 6 / 7 / 2016 Another Day Lost: 1906 and counting... by Syrian artist Issam Kourbaj 1 From Ai Wei Wei to Banksy, we can see art engaging policy and the political sphere. But in an increasingly connected world where cultural production is ever more easily disseminated, how can this engagement be most effective and meaningful? The CEU School of Public Policy’s 2016 annual conference focuses on a series of questions that are not often asked in the world of government or academia. How do artists engage with issues in public policy? How do artistic representations of issues change how they are perceived? Can artists promote wider public engagement in policymaking? How do artists challenge ideas in their societies and to what end? How does humor intersect with politics, censorship, and violence? Focusing on Hungary, India, Mexico, Sudan, and Syria, we are seeking a truly global perspective on issues including democracy, drugs, migration, violence, and censorship. 2 PROGRAM / ART Visit and participate in exhibitions at CEU from June 1-7. Nador u. 11, Body Imaging by Abby Robinson room 002 Precise office hours will be announced soon. Body Imaging, an installation/performance/photography piece, affords a unique collaborative occasion to make photos of all types of bodies, allowing people to display as much/little exhibitionism as they wish in a protected, safe environment. EXAMINATION: Only doctors & photographers examine people’s bodies at distances reserved for lovers. In my performative role as “photo practitioner,” I peer at people’s selected body parts at incredibly close range. -

The Saint John's Bible and Other Materials from HMML’S Collections

Non-Profit Organization WINTER NEWSLETTER U.S. Postage Saint John’s University 2010 PO Box 7300 PAID Collegeville, MN 56321-7300 Saint John’s University 320-363-3514 (voice) Want to receive periodic updates about HMML’s latest adventures? Send your e-mail address to: [email protected] and we will add you to our list. We promise not to spam you, or ever sell or rent your personal information. HMML Board of Overseers Jay Abdo Tom Joyce, Chair Joseph S. Micallef, Edina, Minnesota Minneapolis, Minnesota Founder Emeritus St. Paul, Minnesota James Hurd Anderson Ruth Mazo Karras Minneapolis, Minnesota Minneapolis, Minnesota Anne Miller Edina, Minnesota Nina Archabal Thomas A. Keller III St. Paul, Minnesota Saint Paul, Minnesota Diana E. Murphy Minneapolis, Minnesota Joanne Bailey Steven Kennedy Newport, Minnesota Minneapolis, Minnesota Kingsley H. Murphy, Jr. St. Louis Park, Minnesota Thomas J. Barrett Lyndel I. King Minneapolis, Minnesota Minneapolis, Minnesota Michael Patella, OSB Collegeville, Minnesota Ron Bosrock Abbot John Klassen, OSB St. Paul, Minnesota Collegeville, Minnesota Dan Riley Minneapolis, Minnesota Conley Brooks, Jr. David Klingeman, OSB Minneapolis, Minnesota Collegeville, Minnesota Lois Rogers Long Lake, Minnesota Nicky B. Carpenter, Robert Koopmann, OSB Lifetime Member Collegeville, Minnesota Aelred Senna, OSB Wayzata, Minnesota Collegeville, Minnesota Harriet Lansing Albert J. Colianni Jr. St. Paul, Minnesota Robert L. Shafer Minneapolis, Minnesota New York, New York Dale Launderville, OSB Patrick Dewane Collegeville, Minnesota -

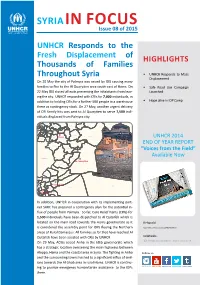

Syria in Focus, Issue 08

Syria IN FOCUSIssue 08 of 2015 UNHCR Responds to theْ Fresh Displacement of HIGHLIGHTS Thousands of Families Throughout Syria • UNHCR Responds to Mass Displacement On 20 May the city of Palmyra was seized by ISIS causing many families to flee to the Al Quaryiten area south east of Homs. On • Safe Road Use Campaign 22 May ISIS closed all exits preventing the inhabitants from leav- Launched ing the city. UNHCR responded with CRIs for 7,000 individuals, in addition to holding CRIs for a further 500 people in a warehouse • Hope alive in IDP Camp there as contingency stock. On 27 May, another urgent delivery of CRI family kits was sent to Al Quaryiten to serve 7,500 indi- viduals displaced from Palmyra city. Sabourah Mesyaf Hama Sheikh Badr Wadi Al-E'ion E'qierbat As_Salamiyeh Bari Al_sharqi Harbanifse A'wag Dreikisch As_Sukhnah Tall Daww Talpesa Al-Qabo Safita Shin Ain_An_Nasr Al_Maghrim Jabb_Ashragh Ten Nor Homs Homs UNHCR 2014 Tal_Kalakh Hadida Furqlus END OF YEAR REPORT Al_Quasir Al-Ruqama Tadmor “Voices from the Field” Hassia Available Now Lebanon Sadd Mahin Al- Quaryiten Dayr_Atiyah An_Nabk Yabrud Assal Al_Warad Jayrud Ma'lual Saraghia Rankuss Raghiba Madaja Saidnaya Al Qutaifeh At_Tal Sab'a Biar Ain_Alfija AL_Dumayr Duma Qatana DamascusAn_Nashabya In addition, UNHCR in cooperation with its implementing part- ner SARC has prepared a contingency plan for the potential in- flux of people from Palmyra. So far, Core Relief Items (CRIs) for 1,500 individuals have been dispatched to Al Qutaifeh which is located on the main road towards the Homs governorate as it Refworld: is considered the assembly point for IDPs fleeing the Northern http://www.refworld.org/docid/54f814604.html areas of Rural Damascus.