Aristocratic Society in Abruzzo, C.950-1140

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COGNOME NOME DATANASCITA LUOGONASCITA INDIRIZZO COMUNERESID Aceto Giovannino 05-Mar-66 Spoltore Via Carso,7 Rosciano Agresta

COGNOME NOME DATANASCITA LUOGONASCITA INDIRIZZO COMUNERESID Aceto Giovannino 05-mar-66 Spoltore via Carso,7 Rosciano Agresta Nicola 28-ott-46 Moscufo via Carducci,15 Moscufo Agresta Cristoforo 25-lug-49 Moscufo via Kennedy,105 Pescara Agresta Davide 17-ago-49 Moscufo via Puccini,27 Moscufo Alfiero Emanuele 14-mar-48 Campomarino via Abruzzo,21 Montesilvano Amicarelli Alfonso 01-gen-50 Sulmona via Tommasi,17 Pescara Angrilli Bruno 29-mar-54 Pescara via Senna 15/2 Montesilvano Anzoletti Pasquale 16-apr-49 Moscufo viale della Libertà,11 Moscufo Ascenzo Francesco 18-dic-59 S.Valentino via Trovigliano,18 S.Valentino Ascenzo Simone 01-gen-89 Popoli via Rigopiano 35 Pescara Assetta Raimondo 02-set-66 Chieti via Costa delle Plaie 12 Alanno Assetta Antonio 24-feb-38 Alanno via Costa delle Plaie 12 Alanno Babore Antonio 15-mar-62 Cepagatti via Piave,58 Cepagatti Baccanale Francesco 20-lug-50 Farindola C.da Valloscuro Penne Balbo Andrea 15-mag-85 Pescara via Castellano,4 Montesilvano Baldassarre Antonio 06-lug-53 Rosciano via Venezia 7 Pescara Bardilli Leonardo 21-gen-46 Picciano C.da Pagliari 10 Picciano Basciano Roberto 10-feb-78 Chieti via Tiburtina,17 Manoppello Scalo Basile Luciano 13-lug-82 Pescara via Petrarca 18 Moscufo Bassetta Emiliano 11-set-76 Pescara via Marco Polo 10 Montesilvano Battistelli Ermanno 19-feb-52 Pescara C.da Costa Pagliola,2 Cugnoli Bellante Domenico 06-gen-41 Città S.A. via Fagnano,20 Città S.Angelo Bellante Tommaso 13-ott-69 Città S.A. via Fagnano,20 Città S.Angelo Berardi Giulio 10-apr-52 Pescara via Pascoli,167 Cappelle sul Tavo Berardinelli Mario 28-giu-46 Pianella via Piano Villa s.Giovanni,13 Rosciano Berardinucci Roberto 07-nov-47 S.Giovanni T. -

Abruzzo: Europe’S 2 Greenest Region

en_ambiente&natura:Layout 1 3-09-2008 12:33 Pagina 1 Abruzzo: Europe’s 2 greenest region Gran Sasso e Monti della Laga 6 National Park 12 Majella National Park Abruzzo, Lazio e Molise 20 National Park Sirente-Velino 26 Regional Park Regional Reserves and 30 Oases en_ambiente&natura:Layout 1 3-09-2008 12:33 Pagina 2 ABRUZZO In Abruzzo nature is a protected resource. With a third of its territory set aside as Park, the region not only holds a cultural and civil record for protection of the environment, but also stands as the biggest nature area in Europe: the real green heart of the Mediterranean. en_ambiente&natura:Layout 1 3-09-2008 12:33 Pagina 3 ABRUZZO ITALY 3 Europe’s greenest region In Abruzzo, a third of the territory is set aside in protected areas: three National Parks, a Regional Park and more than 30 Nature Reserves. A visionary and tough decision by those who have made the environment their resource and will project Abruzzo into a major and leading role in “green tourism”. Overall most of this legacy – but not all – is to be found in the mountains, where the landscapes and ecosystems change according to altitude, shifting from typically Mediterranean milieus to outright alpine scenarios, with mugo pine groves and high-altitude steppe. Of all the Apennine regions, Abruzzo is distinctive for its prevalently mountainous nature, with two thirds of its territory found at over 750 metres in altitude.This is due to the unique way that the Apennine develops in its central section, where it continues to proceed along the peninsula’s -

AMELIO PEZZETTA Via Monteperalba 34 – 34149 Trieste; E-Mail: [email protected]

Atti Mus. Civ. Stor. Nat. Trieste 58 2016 57/83 XII 2016 ISSN: 0335-1576 LE ORCHIDACEAE DELLA PROVINCIA DI CHIETI (ABRUZZO) AMELIO PEZZETTA Via Monteperalba 34 – 34149 Trieste; e-mail: [email protected] Riassunto – Il territorio della provincia di Chieti (regione Abruzzo) misura 2.592 km² e occupa da nord a sud l'area com- presa tra le valli dei fiumi Pescara e Trigno, mentre da sud-ovest a nord-ovest lo spartiacque di vari massicci montuosi lo separa da altre province. Nel complesso è caratterizzato da una grande eterogeneità ambientale che consente l'attec- chimento di molte specie vegetali. Nel presente lavoro è riportato l’elenco floristico di tutte le Orchidacee comprendenti 88 taxa e 21 ibridi. A sua volta l'analisi corologica evidenzia la prevalenza degli elementi mediterranei seguita da quelli eurasiatici. Parole chiave: Chieti, Orchidaceae, check-list provinciale, elementi floristici. Abstract – The province of Chieti (Abruzzo Region) measuring 2,592 square kilometers and from north to south occupies the area between the valleys of the rivers Trigno and Pescara while from the south-west to north-west the watershed of several mountain ranges separating it from other provinces. In the complex it is characterized by a great diversity envi- ronment that allows the engraftment of many plant species. In this paper it contains a list of all the Orchids flora including 88 taxa and 21 hybrids. In turn chorological analysis highlights the prevalence of Mediterranean elements followed by those Eurasian. Keywords: Chieti, Orchidaceae, provincial check-list, floristic contingents. 1. - Inquadramento dell'area d'indagine Il territorio della provincia di Chieti copre la superficie di 2.592 km², com- prende 104 comuni e la sua popolazione attuale e di circa 397000 abitanti. -

Ammessi Provincia PESCARA

COGNOME NOME DATANASCITA LUOGONASCITA PROVNASCITAINDIRIZZO COMUNERESID Aceto Giovannino 05/03/1966 Spoltore PEvia Carso,7 Rosciano Agresta Nicola 28/10/1946 Moscufo PEvia Carducci,15 Moscufo Agresta Cristoforo 25/07/1949 Moscufo PEvia Kennedy,105 Pescara Agresta Davide 17/08/1949 Moscufo PEvia Puccini,27 Moscufo Alfiero Emanuele 14/03/1948 Campomarino CBvia Abruzzo,21 Montesilvano Ambrosini Abele 08/02/1970 Pescara PEvia Piemonte 21 Cepagatti Amicarelli Alfonso 01/01/1950 Sulmona AQvia Tommasi,17 Pescara Angrilli Bruno 29/03/1954 Pescara PEvia Senna 15/2 Montesilvano Ansidei Bruno 07/04/1947 Bellante TEvia Cadorna 48 Montesilvano Anzoletti Pasquale 16/04/1949 Moscufo PEviale della Libertà,11 Moscufo Ascenzo Francesco 18/12/1959 S.Valentino PEvia Trovigliano,18 S.Valentino Ascenzo Simone 01/01/1989 Popoli PEvia Rigopiano 35 Pescara Assetta Antonio 24/02/1938 Alanno PEvia Costa delle Plaie 12 Alanno Assetta Felice 05/11/1967 Alanno PEvia Costa delle Plaie 12 Alanno Assetta Raimondo 02/09/1966 Chieti CHvia Costa delle Plaie 12 Alannpo Babore Antonio 15/03/1962 Cepagatti PEvia Piave,58 Cepagatti Baccanale Francesco 20/07/1950 Farindola PEC.da Valloscuro Penne Balbo Andrea 15/05/1985 Pescara PEvia Castellano,4 Montesilvano Balducci Giuliano 15/06/1944 Montemarciano ANvia Paolucci 73 Pescara Bardilli Leonardo 21/01/1946 Picciano PEC.da Pagliari 10 Picciano Basciano Roberto 10/02/1978 Chieti CHvia Tiburtina,17 Manoppello Scalo Basile Luciano 13/07/1982 Pescara PEvia Petrarca 18 Moscufo Bassetta Emiliano 11/09/1976 Pescara PEvia Marco Polo 10 Montesilvano Battistelli Ermanno 19/02/1952 Pescara PEC.da Costa Pagliola,2 Cugnoli Bellante Domenico 06/01/1941 Città S.A. -

STORIA in COMUNE Brochure 4Ante

Con la partecipazione di Associazione Culturale “Civita dell’Abbadia” Brittoli Penne PRO-LOCO 2 , alla scoperta dell’entroterra CASANOVA pescarese Carpineto della Nora Pietranico Castiglione a Casauria Rosciano In collaborazione con Catignano San Valentino in A.C. ARCHIVIO DI STATO DI PESCARA Civitaquana Scafa Civitella Casanova Serramonacesca Corvara Tocco Da Casauria Con il patrocinio di Direzione tecnica Cugnoli Torre Dè Passeri Strada Prati, 4 - Pescara Farindola Turrivalignani INFORMAZIONI E PRENOTAZIONI per TOUR ed ESCURSIONI Info: www.civitadellabbadia.it Montebello di B. Vicoli www.terrautentica.it [email protected] [email protected] Assistenza telefonica: 340.3293577 335.1355146 Nocciano Villa Celiera Chi siamo Civitaquana, Civitella Casanova, Corvara, Cugnoli, I pannelli contenenti le mappe del territorio Frutto di una millenaria tradizione casearia è il L’Associazione Culturale Civita dell’Abbadia si Farindola, Montebello di Bertona, Nocciano, Penne, evidenziano i punti di maggior interesse turistico ed i pecorino di Farindola, già famoso in epoca romana, costituisce nell’Ottobre del 2009 quando un gruppo Pietranico, Rosciano, San Valentino in Abruzzo percorsi panoramici che rimarranno impressi nella prodotto con una tecnica antica e particolare con di persone locali appassionate e dinamiche, decide di Citeriore, Scafa, Serramonacesca, Tocco da Casauria, memoria dei visitatori. l’utilizzo del caglio di maiale. unirsi per concretizzare l’amore per il proprio Torre de Passeri, Turrivalignani, Vicoli e Villa A questi si è aggiunta la pubblicazione di una guida Il formaggio è l’ingrediente principe di diverse territorio, la sua natura incontaminata, la sua storia e Celiera turistica, lo sviluppo di un’applicazione per cellulari, pietanze locali ed è alla base di un famoso piatto che le sue eccellenze enogastronomiche. -

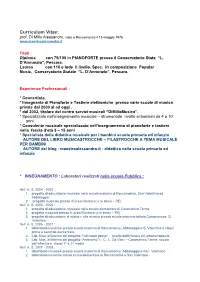

Curriculum Vitae: Prof

Curriculum Vitae: prof. Di Millo Alessandro, nato a Roccamorice il 15 maggio 1976 www.maestroalessandro.it Titoli : Diploma con 75/100 in PIANOFORTE presso il Conservatorio Stata “L. D’Annunzio”, Pescara. Laurea con 110 e lode II livello. Spec. In composizione Popular Music, Conservatorio Statale “L. D’Annunzio”, Pescara. Esperienze Professionali : * Concertista. * Insegnante di Pianoforte e Tastiere elettroniche presso varie scuole di musica private dal 2000 al ad oggi . * dal 2002, titolare del centro servizi musicali “DiMilloMusica”. * Specializzato nell’insegnamento musicale – strumentale rivolto ai bambini da 4 a 10 anni. * Consulente musicale specializzato nell’insegnamento di pianoforte e tastiere nella fascia d’età 3 – 15 anni * Specialista della didattica musicale per i bambini scuola primaria ed infanzia AUTORE DEL LIBRO MUSICASTROCCHE – FILASTROCCHE A TEMA MUSICALE PER BAMBINI AUTORE del blog : maestroalessandro.it - didattica nella scuola primaria ed infanzia * INSEGNAMENTO : Laboratori realizzati nella scuola Pubblica : Nell’ A. S. 2004 - 2005_: 1. progetto di educazione musicale nella scuola materna di Roccamorice, San Valentino ed Abbateggio. 2. progetto musicale presso il Liceo Ravasco (v.le bovio – PE) Nell’ A. S. 2005 - 2006 : 1. progetto di educazione musicale nella scuola elementare di Caramanico Terme 2. progetto musicale presso il Liceo Ravasco (v.le bovio – PE) 3. progetto di educazione al suono e alla musica presso scuola materna Istituto Comprensivo S. Valentino - Nell’ A. S. 2006 - 2007 : 1. laboratorio musicale presso scuola materna di Roccamorice, Abbateggio e S. Valentino e classi prima e seconda elementare. 2. Lab. Mus. all’interno del progetto “Col corpo posso” - scuola dell’infanzia di Lettomanoppello - 3. Lab. Mus. all’interno del progetto “Animiamo” I . -

PESCARA, IL VOTO ALLA PROVINCIA Centrodestra Con 8 Liste, Centrosinistra Con 4 in Corsa L’Ex Biancazzurro Martorella, Torna in Pista Anche Di Girolamo COLLEGIO N

DOMENICA CB IL CENTRO 20 10 maggio 2009 ELEZIONI PESCARA, IL VOTO ALLA PROVINCIA Centrodestra con 8 liste, centrosinistra con 4 In corsa l’ex biancazzurro Martorella, torna in pista anche Di Girolamo COLLEGIO N. 1 COLLEGIO N. 2 COLLEGIO N. 3 COLLEGIO N. 4 ALANNO: Brittoli, Catignano, Corvara, Cugnoli, Noccia- CEPAGATTI: Rosciano CITTA’ SANT’ANGELO: Elice CIVITELLA CASANOVA: Carpineto, Civitaquana, Farin- no, Pietranico dola, Montebello di Bertona, Vicoli, Villa Celiera Candidato Candidato Candidato Candidato CUZZI Gaetano (Patto riformista) DI GIANDOMENICO Gaetano (Patto riformista) SIMONE Nicola (Patto riformista) DI GIANDOMENICO Tonino (Patto riformista) DAMIANI Victor (Mpa) TRABUCCO Davide (Mpa) PETRINI Giulio (Mpa) SCARFAGNA Romano (Mpa) DIODORO Giuliano (Lega Nord) FERRARA Berardino (Lega nord) STASIO Donatello (Lega nord) ANDREOLI Simona (Lega nord) ERISIO Tocco (Partito democratico) PASSERI Gianfranco (Partito democratico) DEL DUCHETTO Rocco (Partito democratico) CHIAVAROLI Francesco (Partito democratico) DE VICO Antonio (Udc) SPERANZA Domenicantonio (Udc) BAIOCCHI Vincenzo (Udc) SANTUCCI Gabriele (Udc) CUZZI Fiorello (Italia dei Valori) BORGIA Camillo (Italia dei valori) DI STEFANO Giuseppe (Italia dei valori) TRONO Leone (Italia dei valori) ANGELINI Sandro (Forza nuova) BUSCARINI Federica (Forza nuova) ASTOLFI Luca (Forza nuova) PERRI Rinaldo (Forza nuova) DI SANO Alessandro (Sinistra) FABIANI Fernando (Sinistra) FABIANI Fernando (Sinistra) DELLA ROVERE Giuseppe (Sinistra) DI GREGORIO Maurizio (Pescara Futura) COLA Francesco (Rialzati Abruzzo) RUGGERI Roberto (Rialzati Abruzzo) LORETI Innocenzo (Rialzati Abruzzo) DI BENEDETTO Antonio (Rif. comunista) RAPATTONI Walter (Rifondazione comunista) CONTENTO Stefania (Rifondazione comunista) DI NARDO Antonio (Rifondazione comunista) COLANGELO Camillo (Il popolo della libertà) VERZULLI Leando (Il popolo della libertà) PRESUTTI Francesco (Il popolo della libertà) PETROCCO Lucio (Il popolo della libertà) DI BENIGNO Sandra (Provincia protagonista) MARRAMIERO Pierluigi (Prov. -

Cappelle Sul Tavo. Nomina Composizione Struttura Organizzativa

COPIA SETTORE PATRIMONIO, ATTIVITA' TECNOLOGICHE E PROTEZIONE CIVILE Registro Generale N. 877 del 02/05/2018 Registro di Settore N. 515 del 02/05/2018 DETERMINAZIONE DEL DIRIGENTE OGGETTO : CENTRALE UNICA DI COMMITTENZA MONTESILVANO - COLLECORVINO - CAPPELLE SUL TAVO. COMPOSIZIONE STRUTTURA ORGANIZZATIVA DEDICATA ALL'ACQUISIZIONE DI LAVORI, FORNITURE E SERVIZI. IL DIRIGENTE Premesso che: · con Delibera C.C. n. 3 del 28/01/2016 questa amministrazione comunale ha aderito alla SUA-PE approvandone lo schema di convenzione ed il relativo regolamento per il funzionamento, sulla base del comma 3-bis dell' art. 33 del D.Lgs. 163/2006 “Codice dei contratti pubblici di lavori, servizi e forniture”; · ai sensi dell' art. 4 della suddetta convenzione la “SUA-PE si impegna, entro 20 giorni lavorativi dalla ricezione della richiesta da parte dell'Ente aderente, ad attivare la procedura di gara”; · nel mese di dicembre 2016 il Comune di Montesilvano ha richiesto alla SUA-PE, secondo le modalitàdi cui alla predetta convenzione, l'espletamento di alcune procedure di gara; · la SUA-PE, nonostante le numerose sollecitazioni ricevute, non ha ancora provveduto all' attivazione di tutte le procedure di gara richieste; · i Responsabili della SUA-PE hanno evidenziato l' esistenza di problematiche strutturali che non consentono di fatto alla stessa di garantire le tempistiche di gara richieste dalle amministrazioni comunali aderenti; · con deliberazione di Giunta comunale n° 139 del 14.06.2017 è stato fornito al Dirigente del Settore Patrimonio, Attività Tecnologiche -

Stampa Del 15/10/2016 - 09:42:46)

TABULATO DI DESIGNAZIONE - CRA01 - categoria: ALP - da:13/10/2016 a:19/10/2016 (stampa del 15/10/2016 - 09:42:46) CATEG. N. GARA RIS. CAMPO ORARIO ARBITRO AA1 AA2 O.A. GARA INDIRIZZO O.T. LOCALITA QUARTO ADD1 ADD2 TUTOR ALP A 4 SCAFA CAST COMUNALE 15/10/2016 (A) PERFETTO BRYAN PES BARBERINI SPORTING VIA P. TOGLIATTI 2 18:00 CLUB SCAFA PE 1 LND -Pescara ALP A 52 ATLETICO MONTESILVANO MONTESILVANO VIA 15/10/2016 (A) D'AMBROSIO GIORGIA VIRTUS MONTESILVANO FOSCOLO 19:30 PES COLLE VIA UGO FOSCOLO 1 LND MONTESILVANO PE -Pescara ALP A 1 TORRE CALCIO COMUNALE 16/10/2016 (A) CHIAVAROLI STEFANO FLACCO PORTO PESCARA LOC. VASTO PIANE 10:30 PES TOCCO DA CASAURIA PE 1 LND -Pescara ALP A 51 PRO TIRINO CALCIO SAN MARCOATERNUM 16/10/2016 (A) PIERMATTEI IVANO PES PESCARA VIA A.MORO Q.RE CEP 10:30 LETTESE S.DONATO 1 LND PESCARA PE -Pescara ALP A 2 PENNE CALCIO PENNE COLANGELO C.DA 17/10/2016 (A) CHIAVAROLI MATTEO CANTERA ADRIATICA OSSICELLI 16:00 PES PESCARA STRADA POV. 151 PER 1 LND LORETO A. -Pescara PENNE PE ALP A 3 VERLENGIA CALCIO MONTESILVANO VIA 17/10/2016 (A) DEI ROCINI FRANCESCO GLADIUS PESCARA 2010 FOSCOLO 17:15 PES VIA UGO FOSCOLO 1 LND MONTESILVANO PE -Pescara ALP A 6 SQUALI PESCARA SUD ADRIANO FLACCO 17/10/2016 (A) TAGLIERI MANUEL PES FATER ANGELINI ABRUZZO ANTISTADIO VIA PEPE 15:30 PESCARA PE 1 LND -Pescara ALP A 5 SAN GABRIELE PESCARA PESCARA 18/10/2016 (A) LOMBARDI DOMENICO 2000 CALCIO VIA IMELE 16:00 PES ACQUAESAPONE PESCARA PE 1 LND -Pescara Documento creato elettronicamente il 15/10/2016 alle ore 09:42:46 da IP 93.41.100.204 con il Sistema Sinfonia4You. -

Statuto Comunale; E) Regolamento Del Consiglio Comunale; F) Strumenti Urbanistici

Ministero dell'Interno - http://statuti.interno.it COMUNE DI PIETRANICO STATUTO Delibera n. 9 del 06.06.2003 Ministero dell'Interno - http://statuti.interno.it TITOLO I PRINCIPI FONDAMENTALI Art. 1Definizione (Artt. 3 e 6 del T.U. 18 agosto 2000, n. 267) 1.Il Comune di Pietranico, Ente Locale Autonomo, rappresenta la propria comunità, ne cura gli interessi e ne promuove lo sviluppo secondo i principi della Costituzione, della legge generale dello Stato e del principio di sussidiarietà. Art. 2 Autonomia (Artt. 3 e 6 del T.U. 18 agosto 2000, n. 267) 1. Il Comune ha autonomia statutaria, normativa, organizzativa e amministrativa, nonché autonomia impositiva e finanziaria nell’ambito dello statuto e dei propri regolamenti, e delle leggi di coordinamento della finanza pubblica. 2. Il Comune ispira la propria azione al principio di solidarietà operando per affermare i diritti dei cittadini, per il superamento degli squilibri economici, sociali, civili e culturali, e per la piena attuazione dei principi di eguaglianza e di pari dignità sociale, dei sessi, e per il completo sviluppo della persona umana. 3. Il Comune, nel realizzare le proprie finalità, assume il metodo della programmazione; persegue il raccordo fra gli strumenti di programmazione degli altri Comuni, della Provincia, della Regione, e dello Stato. 4. L’attività dell’amministrazione comunale è finalizzata al raggiungimento degli obiettivi fissati secondo i criteri dell’economicità di gestione, dell’efficienza e dell’efficacia dell’azione; persegue inoltre obiettivi di trasparenza e semplificazione. 5. Il Comune, per il raggiungimento dei detti fini, promuove anche rapporti di collaborazione e scambio con altre comunità locali, anche di altre nazioni, nei limiti e nel rispetto degli accordi internazionali. -

BRITTOLI Via G

1 AL SINDACO DEL COMUNE DI BRITTOLI Via G. Garibaldi, 5 65010 – Brittoli (PE) Oggetto: consegna progetto di valorizzazione culturale e turistica “TERRA AUTENTICA. Viaggio alla scoperta dell’entroterra pescarese”. Visto l’Avviso del Parco Nazionale del Gran Sasso e Monti della Laga dell’8.2.2019 circa la concessione di contributi per la realizzazione d’interventi finalizzati alla salvaguardia, valorizzazione, fruizione, conoscenza e promozione dei valori e delle risorse ambientali, naturalistiche, paesaggistiche, demo-etno-antropologiche, archeologiche, storiche e culturali del territorio – Area Vestina; Per quanto previsto dalla scheda progetto “TERRA AUTENTICA. Viaggio alla scoperta dell’entroterra pescarese” circa le finalità e gli obbiettivi da perseguire per la valorizzazione turistica dell’area Vestina; Viste le Delibere di Giunta dei Comuni di Brittoli (Delibera di Giunta n° 25 del 27.2.2019), Castiglione A Casauria (Delibera di Giunta n° 13 del 20.2.2019), Corvara (Delibera di Giunta n° 8 del 22.2.2019), Farindola (Delibera di Giunta n° 28 del 14.2.2019) e Montebello di Bertona (Delibera di Giunta n° 9 del 20.2.2019) con cui è stata recepita la scheda progetto di cui sopra; Vista la Vs. successiva Delibera di Giunta n° 25 del 27/2/2019 con cui avete accettato la designazione a capofila dell’iniziativa; Richiamata la Vs. istanza di contributo; Vista la comunicazione protocollo n° 0015831/19 del 27.12.2019 del Parco Nazionale del Gran Sasso e Monti della Laga circa la concessione di un contributo pari a € 40,000,00 (quarantamila/00) per la progettazione e realizzazione delle misure ivi previste dal progetto “TERRA AUTENTICA. -

Spettabile Azienda

Sviluppo Economico dei Territori Parallelo42 contemporary art Pagina 1 di 5 Via Brunelleschi 29 65124 Pescara Info +39 3389744591 e-mail: [email protected] Sviluppo Economico dei Territori COMUNICATO STAMPA BREVE Il Business in Abruzzo si fa con Arte&Gusto Imprenditori abruzzesi, olandesi, turchi e russi per una tre giorni tra arte ed enogastronomia. … un racconto di luoghi terre e sapori, degustazioni e incontri, parole e pensieri di mondi diversi, per accendere nuove fascinazioni, nuove visioni di panorami incantati, preziosi racconti di dame e cavalieri, incastonati nelle sfarzose architetture, da reinventare con nuovi sogni … E' tutto pronto per la Biennale Arte &Gusto 2014, un manifestazione internazionale ideata e realizzata da Parallelo42 e Top Solutions, e promossa dalla Camera di Commercio di Pescara. Tre giorni di convegni su business, arte e enogastronomia, una mostra di artisti internazionali, degustazioni di prodotti tipici e accordi commerciali tra realtà provenienti da Paesi diversi; un tour per immergersi nelle bellezze artistiche e naturali del territorio abruzzese. Dal 5 al 7 novembre,con manifestazione conclusiva prevista per il 5 dicembre, in location di alto prestigio, avranno luogo convegni, mostre, degustazioni e Business to Business ai quali parteciperanno oltre alla rappresentanza italiana, delegazioni da Olanda, Turchia e Russia, formate da rappresentanti istituzionali, delle associazioni imprenditoriali e da esponenti del mondo dell’arte oltre che da buyer interessati a stringere accordi commerciali con le realtà imprenditoriali locali. Un programma ricco e di altissimo livello, che coinvolgerà aziende partner del territorio nonché i comuni della provincia di Pescara che hanno aderito al progetto: Abbateggio, Bussi sul Tirino, Castiglione a Casauria, Cepagatti,Collecorvino, Cugnoli, Pietranico, Rosciano, Tocco da Casauria e Pescara stessa.