Model Display Nameplates by Galería De Clásicos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I MIEI 40 ANNI Di Progettazione Alla Fiat I Miei 40 Anni Di Progettazione Alla Fiat DANTE GIACOSA

DANTE GIACOSA I MIEI 40 ANNI di progettazione alla Fiat I miei 40 anni di progettazione alla Fiat DANTE GIACOSA I MIEI 40 ANNI di progettazione alla Fiat Editing e apparati a cura di: Angelo Tito Anselmi Progettazione grafica e impaginazione: Fregi e Majuscole, Torino Due precedenti edizioni di questo volume, I miei 40 anni di progettazione alla Fiat e Progetti alla Fiat prima del computer, sono state pubblicate da Automobilia rispettivamente nel 1979 e nel 1988. Per volere della signora Mariella Zanon di Valgiurata, figlia di Dante Giacosa, questa pubblicazione ricalca fedelmente la prima edizione del 1979, anche per quanto riguarda le biografie dei protagonisti di questa storia (in cui l’unico aggiornamento è quello fornito tra parentesi quadre con la data della scomparsa laddove avve- nuta dopo il 1979). © Mariella Giacosa Zanon di Valgiurata, 1979 Ristampato nell’anno 2014 a cura di Fiat Group Marketing & Corporate Communication S.p.A. Logo di prima copertina: courtesy di Fiat Group Marketing & Corporate Communication S.p.A. … ”Noi siamo ciò di cui ci inebriamo” dice Jerry Rubin in Do it! “In ogni caso nulla ci fa più felici che parlare di noi stessi, in bene o in male. La nostra esperienza, la nostra memoria è divenuta fonte di estasi. Ed eccomi qua, io pure” Saul Bellow, Gerusalemme andata e ritorno Desidero esprimere la mia gratitudine alle persone che mi hanno incoraggiato a scrivere questo libro della mia vita di lavoro e a quelle che con il loro aiuto ne hanno reso possibile la pubblicazione. Per la sua previdente iniziativa di prender nota di incontri e fatti significativi e conservare documenti, Wanda Vigliano Mundula che mi fu vicina come segretaria dal 1946 al 1975. -

Porsche in Le Mans

Press Information Meet the Heroes of Le Mans Mission 2014. Our Return. Porsche at Le Mans Meet the Heroes of Le Mans • Porsche and the 24 Hours of Le Mans 1 Porsche and the 24 Hours of Le Mans Porsche in the starting line-up for 63 years The 24 Hours of Le Mans is the most famous endurance race in the world. The post-war story of the 24 Heures du Mans begins in the year 1949. And already in 1951 – the pro - duction of the first sports cars in Stuttgart-Zuffenhausen commenced in March the previous year – a small delegation from Porsche KG tackles the high-speed circuit 200 kilometres west of Paris in the Sarthe department. Class victory right at the outset for the 356 SL Aluminium Coupé marks the beginning of one of the most illustrious legends in motor racing: Porsche and Le Mans. Race cars from Porsche have contested Le Mans every year since 1951. The reward for this incredible stamina (Porsche is the only marque to have competed for 63 years without a break) is a raft of records, including 16 overall wins and 102 class victories to 2013. The sporting competition and success at the top echelon of racing in one of the world’s most famous arenas is as much a part of Porsche as the number combination 911. After a number of class wins in the early fifties with the 550, the first time on the podium in the overall classification came in 1958 with the 718 RSK clinching third place. -

Gpnuvolari-Trofeolotus-1-10-39895

La scomparsa di Tazio Nuvolari, avvenuta l'11 agosto 1953, destò grande sensazione in tutto il mondo, in particolare, commosse gli uomini della Mille Miglia, Renzo Castagneto, Aymo Maggi e Giovanni Canestrini, i tre che con Franco Mazzotti, scomparso durante la II Guerra Mondiale, avevano ideato e realizzato la "corsa più bella del mondo". Castagneto, il deus ex machina della Mille Miglia, ed i suoi amici erano autenticamente legati al pilota mantovano, non solo per l'affetto e la stima per l'uomo e l'ammirazione che provavano per il grande campione, ma anche per i sentimenti di riconoscenza che gli attribuivano, per essere stato tra coloro che, con le proprie gesta, avevano maggiormente contribuito all'inarrestabile crescita della loro creatura. Per onorarne la memoria, gli organizzatori della Mille Miglia modificarono il percorso tradizionale così da transitare per Mantova. Da allora, venne istituito il GRAN PREMIO NUVOLARI, da destinare al pilota più veloce e quindi da disputarsi sui lunghi rettilinei che percorrono la pianura Padana, partendo da Cremona e transitando per Mantova, fino al traguardo di Brescia. Oltre alle quattro edizioni storiche svoltesi dal 1954 al 1957 e volute dagli organizzatori della 1000 Miglia, ad oggi si sono disputate 30 rievocazioni del GRAN PREMIO NUVOLARI, la formula, regolarità internazionale riservata ad auto storiche. Dal 1991, i soci fondatori di Mantova Corse, Luca Bergamaschi, Marco Marani, Fabio Novelli e Claudio Rossi, continuano nella medesima opera tramandata dai leggendari fondatori della 1000 Miglia. Il fine, lo stesso: consentire ai piloti delle nuove generazioni di cimentarsi sulle vetture che scrissero la storia di quei giorni, rendendo omaggio al più grande, al più ardimentoso al più audace dei loro predecessori: il leggendario Tazio Nuvolari. -

Alo-Decals-Availability-And-Prices-2020-06-1.Pdf

https://alodecals.wordpress.com/ Contact and orders: [email protected] Availability and prices, as of June 1st, 2020 Disponibilité et prix, au 1er juin 2020 N.B. Indicated prices do not include shipping and handling (see below for details). All prices are for 1/43 decal sets; contact us for other scales. Our catalogue is normally updated every month. The latest copy can be downloaded at https://alodecals.wordpress.com/catalogue/. N.B. Les prix indiqués n’incluent pas les frais de port (voir ci-dessous pour les détails). Ils sont applicables à des jeux de décalcomanies à l’échelle 1:43 ; nous contacter pour toute autre échelle. Notre catalogue est normalement mis à jour chaque mois. La plus récente copie peut être téléchargée à l’adresse https://alodecals.wordpress.com/catalogue/. Shipping and handling as of July 15, 2019 Frais de port au 15 juillet 2019 1 to 3 sets / 1 à 3 jeux 4,90 € 4 to 9 sets / 4 à 9 jeux 7,90 € 10 to 16 sets / 10 à 16 jeux 12,90 € 17 sets and above / 17 jeux et plus Contact us / Nous consulter AC COBRA Ref. 08364010 1962 Riverside 3 Hours #98 Krause 4.99€ Ref. 06206010 1963 Canadian Grand Prix #50 Miles 5.99€ Ref. 06206020 1963 Canadian Grand Prix #54 Wietzes 5.99€ Ref. 08323010 1963 Nassau Trophy Race #49 Butler 3.99€ Ref. 06150030 1963 Sebring 12 Hours #11 Maggiacomo-Jopp 4.99€ Ref. 06124010 1964 Sebring 12 Hours #16 Noseda-Stevens 5.99€ Ref. 08311010 1965 Nürburgring 1000 Kms #52 Sparrow-McLaren 5.99€ Ref. -

EVERY FRIDAY Vol. 17 No.1 the WORLD's FASTEST MO·TOR RACE Jim Rathmann (Zink Leader) Wins Monza 500 Miles Race at 166.73 M.P.H

1/6 EVERY FRIDAY Vol. 17 No.1 THE WORLD'S FASTEST MO·TOR RACE Jim Rathmann (Zink Leader) Wins Monza 500 Miles Race at 166.73 m.p.h. -New 4.2 Ferrari Takes Third Place-Moss's Gallant Effort with the Eldorado Maserati AT long last the honour of being the big-engined machines roaring past them new machines, a \'-12, 4.2-litre and a world's fastest motor race has been in close company, at speeds of up to 3-litre V-6, whilst the Eldorado ice-cream wrested from Avus, where, in prewar 190 m.p.h. Fangio had a very brief people had ordered a V-8 4.2-litre car days, Lang (Mercedes-Benz) won at an outing, when his Dean Van Lines Special from Officine Maserati for Stirling Moss average speed of 162.2 m.p.h. Jim Rath- was eliminated in the final heat with fuel to drive. This big white machine was mann, driving the Zink Leader Special, pump trouble after a couple of laps; soon known amongst the British con- made Monza the fastest-ever venue !by tingent as the Gelati-Maserati! Then of winning all three 63-1ap heats for the course there was the Lister-based, quasi- Monza 500 Miles Race, with an overall single-seater machine of Ecurie Ecosse. speed of 166.73 m.p.h. By Gregor Grant The European challenge was completed Into second place came the 1957 win- Photography by Publifoto, Milan by two sports Jaguars, and Harry Schell ner, Jim Bryan (Belond A.P. -

50 YEARS AGO at SEBRING, CALIFORNIA PRIVATEERS USED 550-0070 to TAKE on BARON HUSCHKE VON Hansteinrs FAC- TORY PORSCHES-AND NEAR

50 YEARS AGO AT SEBRING, CALIFORNIA PRIVATEERS USED 550-0070 TO TAKE ON BARON HUSCHKE VON HANSTEINrS FAC- TORY PORSCHES-AND NEARLY BEATTHEM SrORYBYWALEDGAR PHOTOSBYJlAllSrrZANDCOURTESYOF THE EDOARrn~BRCHM L )hn Edgar had an idea. His and film John von Newnann race me. It Edwsi&a was niow a r&ng program. egendary MG "88" Special was an impressive performance. Only Chassis number 552-00M arrived in ~OftetlCaniedhotshoeJaick Pete Lovely3 hornsbuilt "PorscheWagen" $mfor Jack McAfee to debut the Edgar- dcAfee to American road- came closs to it in class. Edgar wibessxl entered Spyder at Sanfa Barbara's 1955 racing victorias and, by 1955, the 550's speed winon MmialDay at Labor Day sportscar races. Unfamiliar Edgar saw no reason why Santa Barbara and at Torrey Pins tn July. 4th the SwakMBWlfty, Mfee managed JN1CAtest wldnY get Weagain in the la?- He studied his footage again and agaln. rw better than fourth. But the car felt right, & and gm-dest Under 15KI-c~mmhins. Won over by ttre 550's superior handling, e~enin the Elfip d a man as camparaWty That car w&s Porsche's new 550 Spyder. he hesitated no further and ordered one large as McAfee, so the driver-engineer In April of 1%5, Edgar had gone. to thrwgh John rn Neurmnn's Cornpew began ta ready #0070 for a Torrey Pines Mintw Fdd outsi& Bakersfield to watch Mason Vm Street in Hd . John sk-hr endurn in October. On September 30, movie idol James Dean was killed in his own 550, bringing national notice to Porsche's new-to- America 550 Spyder. -

The Last Road Race

The Last Road Race ‘A very human story - and a good yarn too - that comes to life with interviews with the surviving drivers’ Observer X RICHARD W ILLIAMS Richard Williams is the chief sports writer for the Guardian and the bestselling author of The Death o f Ayrton Senna and Enzo Ferrari: A Life. By Richard Williams The Last Road Race The Death of Ayrton Senna Racers Enzo Ferrari: A Life The View from the High Board THE LAST ROAD RACE THE 1957 PESCARA GRAND PRIX Richard Williams Photographs by Bernard Cahier A PHOENIX PAPERBACK First published in Great Britain in 2004 by Weidenfeld & Nicolson This paperback edition published in 2005 by Phoenix, an imprint of Orion Books Ltd, Orion House, 5 Upper St Martin's Lane, London WC2H 9EA 10 987654321 Copyright © 2004 Richard Williams The right of Richard Williams to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 0 75381 851 5 Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives, pic www.orionbooks.co.uk Contents 1 Arriving 1 2 History 11 3 Moss 24 4 The Road 36 5 Brooks 44 6 Red 58 7 Green 75 8 Salvadori 88 9 Practice 100 10 The Race 107 11 Home 121 12 Then 131 The Entry 137 The Starting Grid 138 The Results 139 Published Sources 140 Acknowledgements 142 Index 143 'I thought it was fantastic. -

20 7584 7403 E-Mail [email protected] 1958 Brm Type 25

14 QUEENS GATE PLACE MEWS, LONDON, SW7 5BQ PHONE +44 (0)20 7584 3503 FAX +44 (0)20 7584 7403 E-MAIL [email protected] 1958 BRM TYPE 25 Chassis Number: 258 Described by Sir Stirling Moss as the ‘best-handling and most competitive front-engined Grand Prix car that I ever had the privilege of driving’, the BRM P25 nally gave the British Formula One cognoscenti a rst glimpse of British single seater victory with this very car. The fact that 258 remains at all as the sole surviving example of a P25 is something to be celebrated indeed. Like the ten other factory team cars that were to be dismantled to free up components for the new rear-engined Project 48s in the winter of 1959, 258 was only saved thanks to a directive from BRM head oce in Staordshire on the express wishes of long term patron and Chairman, Sir Alfred Owen who ordered, ‘ensure that you save the Dutch Grand Prix winner’. Founded in 1945, as an all-British industrial cooperative aimed at achieving global recognition through success in grand prix racing, BRM (British Racing Motors) unleashed its rst Project 15 cars in 1949. Although the company struggled with production and development issues, the BRMs showed huge potential and power, embarrassing the competition on occasion. The project was sold in 1952, when the technical regulations for the World Championship changed. Requiring a new 2.5 litre unsupercharged power unit, BRM - now owned by the Owen Organisation -developed a very simple, light, ingenious and potent 4-cylinder engine known as Project 25. -

Latest Paintings

ULI EHRET WATERCOLOUR PAINTINGS Latest Paintings& BEST OF 1998 - 2015 #4 Auto Union Bergrennwagen - On canvas: 180 x 100 cm, 70 x 150 cm, 50 x 100 cm, 30 x 90 cm - Framed prints: 50 x 60 cm, 40 x 50 cm, 25 x 30 cm #200 Bernd Rosemeyer „Auto Union 16 Cylinder“ - On canvas: 120 x 160 cm, 100 x 140 cm, 70 x 100 cm, 50 x 70 cm - Framed prints: 50 x 60 cm, 40 x 50 cm, 25 x 30 cm #468 Rudolf Carraciola / Mercedes W154 - On canvas: 180 x 100 cm, 70 x 150 cm, 50 x 100 cm, 30 x 90 cm - Framed prints: 50 x 60 cm, 40 x 50 cm, 25 x 30 cm #52 Hermann Lang „Mercedes Silberpfeil“ #83 Bernd Rosemeyer „Weltrekordfahrt 1936“ - On canvas: 180 x 100 cm, 70 x 150 cm, 50 x 100 cm, 30 x 90 cm - On canvas: 180 x 100 cm, 70 x 150 cm, 50 x 100 cm, 40 x 80 cm - Framed prints: 50 x 60 cm, 40 x 50 cm, 25 x 30 cm - Framed prints: 50 x 60 cm, 40 x 50 cm, 25 x 30 cm #291 Richard Seaman „Donington GP 1937“ - On canvas: 180 x 100 cm, 70 x 150 cm, 50 x 100 cm, 40 x 80 cm - Framed prints: 50 x 60 cm, 40 x 50 cm, 25 x 30 cm #88 Stirling Moss „Monza Grand Prix 1955“ - On canvas: 120 x 160 cm, 180 x 100 cm, 80 x 150 cm, 60 x 100 cm - Framed prints: 50 x 60 cm, 40 x 50 cm, 25 x 30 cm #277 Jean Pierre Wimille „Talbot Lago T26“ - On canvas: 160 x 120 cm, 150 x 100 cm, 120 x 70 cm, 60 x 40 cm - Framed prints: 50 x 60 cm, 40 x 50 cm, 25 x 30 cm #469 Tazio Nuvolari / Auto Union D-Type / Coppa Acerbo 1938 - On canvas: 180 x 120 cm, 160 x 90 cm, 140 x 70 cm, 90 x 50 cm, 50 x 30 cm - Framed prints: 50 x 60 cm, 40 x 50 cm, 25 x 30 cm - Original: framed 50 x 70 cm, 1.290 Euros original -

Dags Att Se Över Lancia Integrale-Bilarna Inför Den Kommande Racingsäsongen Tycker Tor

Dags att se över Lancia Integrale-bilarna inför den kommande racingsäsongen tycker Tor. Och från rallyns hemtrakter i Värmland kom Kjell till Lanciagaraget för att hämta delar till Lancia Fulvia Coupén för Midnattssolsrallyt 2014. LANCIA FULVIA 50 år 2013. Söndagen den 28 juli var 130 personer med olika Fulviamodeller samlade i italienska Fobello för 50-årsfirandet. Fulvian som deltog i rallyt Peking-Paris, den öppna modellen F&M Special, var på plats – och klubbmästare Per med. Innehåll i detta nummer bl.a. : Sid. 3, Klubbpresentation Sid. 4-8 Ordföranden reste till Padova Sid. 9-12 Salutorg och kommande träffar Sid. 13 Pers arbetsresa till Fobello i april Sid. 14 Anna-Lena & Per i Valsesia 14-24 aug. Sid. 15-20 Schweiz 40 årsjubiléum 6-8 sept. Sid. 21-23 LCÖ, Saltzburg 12-15 sept. Sid. 24-27 Bilutställning Gran Turismo, Nacka, nov. Sid. 28-32 Hector Carcias studentresa 2012 Sid. 33-34 Hänt i garaget Sid. 35 Autoexperten + Pers Saffransskorpor SVENSKA LANCIAKLUBBEN Syfte Klubbens syfte är att samla intresserade Lanciaägare och personer med genuint intresse av dessa bilar för att under trivsamma former: • Öka medlemmarnas insikt i allt som berör Lanciabilarnas teknik, egenskaper, skötsel och historia samt bistå vid problem. • Informera om och ventilera andra frågor som berör veteranbilshobbyn samt relaterade produkter och teknologi. • På bästa sätt bevaka reservdelsfrågan. Styrelse Lars Filipsson. suppleant Herbert Nilsson. Ordförande o Heders- Grahamsvägen 5, 174 46 Sundbyberg president / ansvarig utgivare La Lancia. Tel. 08-6282443 Jacob Ulfssons väg 7A, 647 32 Mariefred E-mail [email protected] Tel. 0159-108 42 Mob. 070-910 94 05 E-mail [email protected] Lanciamodeller Kontaktpersoner Magnus Nilsson. -

Eccellenze Meccaniche Italiane

ECCELLENZE MECCANICHE ITALIANE. MASERATI. Fondatori. Storia passata, presente. Uomini della Maserati dopo i Maserati. Auto del gruppo. Piloti. Carrozzieri. Modellini Storia della MASERATI. 0 – 0. FONDATORI : fratelli MASERATI. ALFIERI MASERATI : pilota automobilistico ed imprenditore italiano, fondatore della casa automobilistica MASERATI. Nasce a Voghera il 23/09/1887, è il quarto di sette fratelli, il primo Carlo trasmette la la passione per la meccanica ALFIERI, all'età di 12 anni già lavorava in una fabbrica di biciclette, nel 1902 riesce a farsi assumere a Milano dalla ISOTTA FRASCHINI, grazie all'aiuto del fratello Carlo. Alfieri grazie alle sue capacità fa carriera e alle mansioni più umili, riesce ad arrivare fino al reparto corse dell'azienda per poi assistere meccanicamente alla maccina vincente della Targa FLORIO del 1908, la ISOTTA lo manda come tecnico nella filiale argentina di Buenos Aires, poi spostarlo a Londra, e in Francia, infine nel 1914 decide, affiancato dai suoi fratelli. Ettore ed Ernesto, di fondare la MASERAT ALFIERI OFFICINE, pur rimanendo legato al marchio ISOTTA-FRASCHINI, di cui ne cura le vetture da competizione in seguito cura anche i propulsori DIATTO. Intanto però, in Italia scoppia la guerra e la sua attività viene bloccata. Alfieri Maserati, in questo periodo, progetta una candela di accensione per motori, con la quale nasce a Milano la Fabbrica CANDELE MASERATI infine progetta un prototipo con base telaio ISOTTA- FRASCHINI, ottenendo numerose vittorie, seguirà la collaborazione con la DIATTO, infine tra il 1925/26, mesce la mitica MASERATI TIPO 26, rivelandosi poi, un'automobile vincente. Il 1929 sarà l'anno della creazione di una 2 vettura la V43000, con oltre 300 CV, la quale raggiungerà i 246 Km/ h, oltre ad altre mitiche vittorie automobilistiche. -

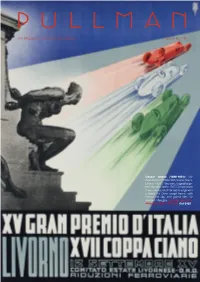

The Magazine of the Pullman Gallery Issue No. 60

The Magazine of the Pullman Gallery Issue No. 60 Cesare Gobbo (1899-1981): ‘XV Gran Premio D’Italia XVII Coppa Ciano, Livorno 1937’. Very rare, original large- format poster dated 1937. Conservation linen mounted and framed to edge with a black Art Deco swept frame, with copper-leaf slip, and glazed with UV resistant Plexiglas. Overall size: 60 x 44 inches (153 x 112 cm). Ref 6462 Playing Ketchup p.52 p.62 p.67 p.3 p.47 p.20 p.21 p.8143 p.46 The Pullman Gallery specializes in objets de luxe dating from 1880-1950. Our gallery in King Street, St. James’s next to Christie’s and our appointment- only studios near Chelsea Bridge, houses London’s An extremely desirable mid-century novelty ice bucket 14 King Street finest collection of rareArt Deco cocktail shakers and in the form of a tomato, the nickel plated body with removable lid complete with realistic leaves and stalk, St. James’s luxury period accessories, sculpture, original posters revealing the original rose-gold ‘mercury’ glass bowl, London SW1Y 6QU and paintings relating to powered transport, as well which keeps the ice from melting too quickly. Stamped as automobile bronzes, trophies, fine scale racing THERMID PARIS, MADE IN FRANCE. French, circa Tel: +44 (0)20 7930 9595 car models, early tinplate toys, vintage car mascots, 1950s. Art Deco furniture, winter sports-related art and Ref 6503 [email protected] objects and an extensive collection of antique Louis Height: 9 inches (23 cm), diameter: 8 inches (20 cm). www.pullmangallery.com Vuitton and Hermès luggage and accessories.