Visions of a New Land

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By Leon Trotsky

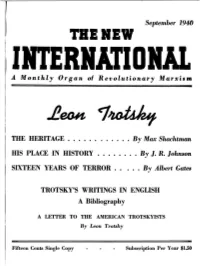

September 1940 TRIRI. A M on thl y Organ of Revolutionary M arxisrn THE HERITAGE .•••........ By Max Shachtman HIS PLACE IN HISTORY • • • • •.. By J. R. Johnson SIXTEEN YEARS OF TERROR . • . By Albert Gates TROTSKY'S WRITINGS IN ENGLISH A Bibliography A LETTER TO THE AMERICAN TROTSKYISTS By Leon Trotsky Fifteen Cents Single Copy Subscription Per Year $1.50 r THE NEW INTERNATIONAL ..4 Mon,hly Organ 01 Ref)olutionary Mar",lam Volume VI September, 1940 No.8 (Whole No. 47) Published ~onthly by NEW INTERNATIONAL Publishing Company, 114 West 14th Street, New York, N. Y. Telephone CHelsea 2·9681. One bit of good news this month is the fact that we have Subscription rates: $1.50 per year; bundles, 10c for 5 copies obtained second class mailing privileges for THE NEW INTER and up. Canada and foreign: $1.75 per year; bundles, 12c for 5 NATIONAL. This will help our program in the coming months. and up. Entered as second·class matter July 10, 1940, at the poet office at New York, N.Y. under the act of March 3, 1879. We succeeded in issuing a 32 page number in memory of Leon Trotsky, and we are going to try to continue with the larger Editor: MAX SHACHTMAN magazine. Business Manager: ALBERT GATES • TABLE OF CONTENTS The October issue is already in preparation. As we told you LEON TROTSKY: THE HERITAGE in August a special election would be published. We had orig By Max Shachtman ----------------------------------------- 147 inally planned this for September, but the tragic death of Trot TROTSKY'S PLACE IN HISTORY sky made necessary that postponement. -

No. 181, November 11, 1977

WfJ/iIlE/iS ",IN(J(J,I/i, 25¢ No. 181 :-..==: )(,~:lJ 11 November 1977 ~-- - ~- -;' :;a. ~I"l,e~reAl. ' t~he·"arty,p. of I tile Russian Revolutioll • i 1 ,. f ~ • Sixtieth Anniversary of the ~ '!'--J t·1&~·- Bolshevik =' .~~~~I....... li.~'" E. ~ tt>c~~ t:~~~~ 1!!1.~ Oust tile Stalirlist Revolution ·~~.· ""I~,~. Bureaucracy! G ,j"§"!ill~'I\i.~.-'1... '-... October! the mood of the moment. The Russian against "Soviet social-imperialism"; program is as valid as it was 40 years The 1917 October Revolution was the ago. One ofits most powerfulpresenta question has been and remains the shaping event of our century. The centrists salute Lenin while ignoring his question of the revolution. The Russian life-long struggle for an international tions is the speech, reprinted below, by seizure of state power 60 years ago by James P. CannonJounder ofAmerican Bolsheviks on November 7, 1917, once the revolutionary Russian proletariat, proletarian vanguard as the roadto new and for all, took the question of the Octobers; and the now-reformist S WP Trotskyism, to the New York branch of led by its Bolshevik vanguard, was a the Socialist Workers Party on 15 workers' revolution out of the realm of monumental advance toward world sloughs offdefense of the USSR as an abstraction and gave it flesh and blood impediment to its social-democratic October 1939. Cannon's speech was socialism. Even today-decades after originally reprinted in the February reality. the usurpation ofpolitical power in the appetites. Only the international Spar It was said once of a book-I think it tacist tendency-the legitimate political 1940 New International; we are repu USSR by the Stalinist bureaucratic blishing it from his book, The Struggle was Whitman's "Leaves of Grass" caste whose counterrevolutionary be continuators of Lenin's Bolsheviks and "who touches this book, touches a of Trotsky's Fourth lnternational for a Proletarian Party, which originally trayals block the international exten appeared in 1943. -

Honour List 2018 © International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY), 2018

HONOUR LIST 2018 © International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY), 2018 IBBY Secretariat Nonnenweg 12, Postfach CH-4009 Basel, Switzerland Tel. [int. +4161] 272 29 17 Fax [int. +4161] 272 27 57 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.ibby.org Book selection and documentation: IBBY National Sections Editors: Susan Dewhirst, Liz Page and Luzmaria Stauffenegger Design and Cover: Vischer Vettiger Hartmann, Basel Lithography: VVH, Basel Printing: China Children’s Press and Publication Group (CCPPG) Cover illustration: Motifs from nominated books (Nos. 16, 36, 54, 57, 73, 77, 81, 86, 102, www.ijb.de 104, 108, 109, 125 ) We wish to kindly thank the International Youth Library, Munich for their help with the Bibliographic data and subject headings, and the China Children’s Press and Publication Group for their generous sponsoring of the printing of this catalogue. IBBY Honour List 2018 IBBY Honour List 2018 The IBBY Honour List is a biennial selection of This activity is one of the most effective ways of We use standard British English for the spelling outstanding, recently published children’s books, furthering IBBY’s objective of encouraging inter- foreign names of people and places. Furthermore, honouring writers, illustrators and translators national understanding and cooperation through we have respected the way in which the nomi- from IBBY member countries. children’s literature. nees themselves spell their names in Latin letters. As a general rule, we have written published The 2018 Honour List comprises 191 nomina- An IBBY Honour List has been published every book titles in italics and, whenever possible, tions in 50 different languages from 61 countries. -

Countering NATO Expansion a Case Study of Belarus-Russia Rapprochement

NATO RESEARCH FELLOWSHIP 2001-2003 Final Report Countering NATO Expansion A Case Study of Belarus-Russia Rapprochement PETER SZYSZLO June 2003 NATO RESEARCH FELLOWSHIP INTRODUCTION With the opening of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) to the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, the Alliance’s eastern boundary now comprises a new line of contiguity with the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) as well as another geopolitical entity within—the Union of Belarus and Russia. Whereas the former states find greater security and regional stability in their new political-military arrangement, NATO’s eastward expansion has led Belarus and Russia to reassess strategic imperatives in their western peripheries, partially stemming from their mutual distrust of the Alliance as a former Cold War adversary. Consequently, security for one is perceived as a threat to the other. The decision to enlarge NATO eastward triggered a political-military “response” from the two former Soviet states with defence and security cooperation leading the way. While Belarus’s military strategy and doctrine remain defensive, there is a tendency of perceiving NATO as a potential enemy, and to view the republic’s defensive role as that of protecting the western approaches of the Belarus-Russia Union. Moreover, the Belarusian presidency has not concealed its desire to turn the military alliance with Russia into a powerful and effective deterrent to NATO. While there may not be a threat of a new Cold War on the horizon, there is also little evidence of a consolidated peace. This case study endeavours to conduct a comprehensive assessment on both Belarusian rhetoric and anticipated effects of NATO expansion by examining governmental discourse and official proposals associated with political and military “countermeasures” by analysing the manifestations of Belarus’s rapprochement with the Russian Federation in the spheres of foreign policy and military doctrine. -

Albert Glotzer Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf1t1n989d No online items Register of the Albert Glotzer papers Finding aid prepared by Dale Reed Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2010 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Register of the Albert Glotzer 91006 1 papers Title: Albert Glotzer papers Date (inclusive): 1919-1994 Collection Number: 91006 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 67 manuscript boxes, 6 envelopes(27.7 Linear Feet) Abstract: Correspondence, writings, minutes, internal bulletins and other internal party documents, legal documents, and printed matter, relating to Leon Trotsky, the development of American Trotskyism from 1928 until the split in the Socialist Workers Party in 1940, the development of the Workers Party and its successor, the Independent Socialist League, from that time until its merger with the Socialist Party in 1958, Trotskyism abroad, the Dewey Commission hearings of 1937, legal efforts of the Independent Socialist League to secure its removal from the Attorney General's list of subversive organizations, and the political development of the Socialist Party and its successor, Social Democrats, U.S.A., after 1958. Creator: Glotzer, Albert, 1908-1999 Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives in 1991. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Albert Glotzer papers, [Box no., Folder no. -

El Gran Terror Una Reevaluación

Lea el LIBRO PROHIBIDO por los SOCIALISTAS El Gran Terror Una Reevaluación Robert Conquest Oxford University Press Oxford, Nueva York, Toronto 1990 Traducción al español de Carlos Eduardo Ruiz Prefacio Es un particularmente apropiado momento para colocar ante el público una reevaluación de El Gran Terror, que avasalló a la Unión Soviética en la década de 1930. Primero, nosotros tenemos ahora suficiente información para establecer casi todo eliminando cualquier disputa. Segundo, El Terror, es, en el presente inmediato de la década de 1990, un asunto político y humano en la URSS. Esto quiere decir, es la más asombrosa, la más crítica, y la más importante agenda del mundo de hoy. Mi libro El Gran Terror fue escrito hace veinte años (aunque cierta cantidad de material adicional entró en ediciones publicadas a comienzos de la década de 1970). El breve período de la revelación Krushcheviana había proporcionado suficiente nueva evidencia, en conjunto con la masa de reportes no-oficiales anteriores, para darle a la historia del período detalles considerables y mutuamente confirmatorios. Sin embargo, había mucho que permanecía como deducción, y hubo vacíos ocasionales, o inadecuadamente verificadas probabilidades, que hacían imposible la certidumbre. Durante los años desde entonces, El Gran Terror se mantuvo como el único completo registro histórico del período –como de hecho, lo hace hasta el día de hoy. Fue recibido como tal, no sólo en Occidente sino también en la mayoría de los círculos en la Unión Soviética. Yo rara vez conocí a un funcionario, académico (o emigrado) soviético, que no lo hubiese leído en inglés, o en una edición rusa publicada en Florencia, o en samizdat [1]; tampoco ninguno de ellos cuestiona su exactitud en general, aún si es capaz de corregir o enmendar unos pocos detalles. -

Rühle-Gerstel

PRODUCED 2005 BY UNZ.ORG ELECTRONIC REPRODUCTION PROHIBITED Alice Ruhle-Gerstel No Verses for Trotsky A Diary in Mexico (1937) HEN WE READ in Cuautla in December "United Front", in Dresden around 1930, when I W [1936] that the Cardenas government had wanted to join the Trotskyists, purely for the sake granted Trotsky asylum—and Fritz [Otto Riihle's of being somehow "involved"—without really son-in-law] rang us to confirm the news—we were knowing what the Trotskyists stood for. delighted. In fact we had no specially close Discussions—no, just conversations with Wolfi relationship to Trotsky. Salus in the Cafe Elektra. And the many times I I had various memories, starting with my half- had wanted to—but never did—send Trotsky a heroic, half-sentimental admiration of 1917 when I telegram of sympathy when yet another country had picked up a picture of him—a postcard show- had deported him. And Otto's critical rejection ing him with a stand-up collar and a bushy of his policies and his portrayal of Trotsky as moustache—in a socialist bookshop in the an arrogant, stern, and somewhat theatrical Gumpendorferstrasse in Vienna and pinned it up revolutionary hero. All in all, a pretty confused over my bed. Then that party game in Prague, picture.... Nevertheless, we were very glad. probably in 1919, when my brother signed himself It was so marvellous that Trotsky was coming "Trotsky" in my family album. Our agitation and to Mexico—for him and for us! Suddenly the my bursting into tears when Otto arrived in Vienna ideological differences fell away; all we were aware in October 1927 and his first words to me after of was the togetherness of being exiled in Mexico; months of separation were: "Trotsky's been and we felt very close to him. -

Labor Officials Remain Silent on One-Hour Work Stoppage

Youngstown CIO Backs Kutcher’s t h e PUBLISHEDMILITANT WEEKLY IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE Civil Rights Rally Vol. XX — No. 10 ?67 NEW YORK, N. Y., MONDAY, MARCH 5, 1956 PRICE: 10 Cent« By Shirley Clark FEB. 27 — A civil liberties rally, sponsored by the Kutcher Civil Rights Committee, is being mobilized by united labor, Negro and civil liberties forces in Youngs town Obiio. Scheduled to be heldi^ on Friday, March 9, at 8 P. M. lean Civil Liberties Union, will at the YMCA, Central Branch, speak on "Civil Liberties — Which Labor Officials Remain Silent tlhe Rally promises to be a Way?" And Mate Lee, an active vigorous demonstration for the civil rights leader in Ohio, will growing demand that Kutcher’s speak on “The Negro’s Struggle job be restored to him finally for Freedom.” aifter nearly eight years of strug gle. Kutcher was fired from ihis CALLING FOR SUPPORT job with the Veterans Adminis The CIO Council has asked all tration for his openly proclaimed its affiliated locals to support the On One-Hour Work Stoppage membership in the- Socialist Civil Liberties Rally. The KCRC Workers Party. is planning to distribute announce In addition bo James Ku'tcher, ments to about 20 of the union ALABAMA NEGRO LEADERS INDICTED IN BUS BOYCOTT the now famous legless veteran, locals. The ACLU and an inter Stevenson Needs A1 Shipka, President of the racial committee are also mailing March 28 Set As Day Mahoning County CIO Council, the Rally program tb their mem will speak on “Labor’s Stake in berships. -

Leon Trotsky Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf296n98nm No online items Register of the Trotsky collection, 1917-1995 Finding aid prepared by Hoover Institution Staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Hernán Cortés Hoover Institution Archives 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA, 94305-6010 (650) 723-3563 [email protected] © 1998, 2016 Register of the Trotsky collection, 92032 1 1917-1995 Title: Leon Trotsky Collection Date (inclusive): 1917-1995 Collection Number: 92032 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Archives Language of Material: Mainly in RussianEnglish Physical Description: 47 manuscript boxes, 4 envelopes, 2 phonorecords, 1 framed painting(20.2 linear feet) Abstract: Writings and correspondence of the Russian revolutionary leader Leon Trotsky, including drafts of articles and books, correspondence with John G. Wright and other leaders of the Socialist Workers Party of the United States, and typed copies of correspondence with V. I. Lenin; correspondence and reports of secretaries of Trotsky and leaders of the Socialist Workers Party, relating especially to efforts to safeguard Trotsky and to his assassination; records of the American Committee for the Defense of Leon Trotsky and of the Commission of Inquiry into the Charges Made against Leon Trotsky in the Moscow Trials; correspondence and writings of Nataliia Sedova Trotskaia and of Lev Sedov; and published and unpublished material relating to Trotsky. Assembled from records of the Socialist Workers Party and from papers of Wright and other party leaders. Also includes detailed summaries of correspondence in the Trotsky Papers at Harvard University. Boxes 1-45 also available on microfilm (50 reels). Phonotape cassette dub of sound recordings also available. -

Stalin-Edvard-Radzinsky.Pdf

THE FIRST IN-DEPTH BIOGRAPHY BASED ON EXPLOSIVE NEW DOCUMENTS FROM RUSSIA’S SECRET ARCHIVES EDVARD RADZINSKY TRANSLATED BY H. T. WILLETTS Preface Prologue: The Name Introduction: An Enigmatic Story ONE: SOSO: HIS LIFE AND DEATH 1.The Little Angel 2. Childhood Riddles 3. The End of Soso TWO: KOBA 4. Enigmatic Koba 5. The New Koba 6. A Grand Master’s Games 7. The Great Utopia 8. The Crisis Manager 9. The Birth of Stalin THREE: STALIN: HIS LIFE, HIS DEATH 10. The October Leaders Meet Their End: Lenin 11. The End of the October Leaders 12. The Country at Breaking Point 13. The Dreadful Year 14. The Congress of Victors 15. The Bloodbath Begins 16. “The People of My Wrath” Destroyed 17. The Fall of “The Party’s Favorite” 18. Creation of a New Country 19. Night Life 20. Tending Terror’s Sacred Flame 21. Toward the Great Dream 22. Two Leaders 23. The First Days of War Interlude: A Family in Wartime 24. Onward to Victory 25. The Leader’s Plan 26. The Return of Fear 27. The Apocalypse That Never Was 28. The Last Secret Afterword Selected Bibliography (removed) Index (removed) NOTE The dates used in this book up to February 1918 follow the old-style Julian calendar, which was in use in Russia until that month. In the nineteenth century the Julian calendar lagged twelve days behind the Gregorian calendar used in the West; in the twentieth century, the Julian calendar lagged thirteen days behind. PREFACE I have been thinking about this book all my life. -

KATSNELSON-DISSERTATION.Pdf

Copyright by Anna Katsnelson 2011 The Dissertation Committee for Anna Katsnelson Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: ETHNIC PASSING ACROSS THE JEWISH LITERARY DIASPORA Committee: Seth Wolitz, Supervisor John Hoberman Naomi Lindstrom Elizabeth Richmond-Garza Sonia Roncador ETHNIC PASSING ACROSS THE JEWISH LITERARY DIASPORA by Anna Katsnelson, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2011 Dedication Dedicated to my husband and best friend Eric, my son Lev, and my parents Alex Katsnelson and Dr. Sofya Katsnelson. Acknowledgements I would like to thank my wonderful advisor Professor Emeritus Seth Wolitz, who guided my project from its inception; he was and remains the model of a gifted and inspiring educator. His intuition, support, and insightful suggestions throughout my university career and the course of this project have been invaluable. Through Professor Wolitz’s influential lectures I have grown as a teacher, but through his tireless dedication and instrumental feedback my project gained depth, sharpened its objective and ultimately led me to have a successful defense. Dr. Naomi Lindstrom’s comments and advice from the beginning of this project have been invaluable but her suggestions once the Brazilian chapters were written really led me in the right direction and allowed me to focus the project and clean it up. Professor Lindstrom first suggested that I make my Brazilian chapters on both Elisa and Clarice Lispector, it was this suggestion that prompted the study of other familial and collaborative pairs like Evgenia Ginzburg and Vassily Aksyonov, and George S. -

Russian Nuclear Warhead Dismantlement Rates and Storage Site Capacity: Implications for the Implementation of START II

Nuclear START Russian Nuclear \Varhead Dismantlement Rates and Storage Site Capacity: Implications for the Implementation of START II and De-alerting Initiatives Joshua Handler Woodrow Wilson School Princeton University Princeton, NJ 08544 ph. 609-258-5692 fax. 609-258-3661 [email protected] CEES Report No. AC-99-01 February 1999 Table of Contents 1. Introduction . 1 2. The Storage Space Crunch . 3 a. The Nuclear Weapons Storage Barrel . 6 Stockpile Size . 8 Numbers of Stored Weapons . 11 Nuclear Warhead Dismantlement Rates . 12 Overloaded Storages? . 15 b. The Eliminated-Weapons Storage Barrel . 16 3. Conclusions . 20 a. Stockpile Size, Storage Space, and Dismantlement Rates . 20 b. Impact on Implementation of Current and Future Strategic Arms Control Agreements . 22 c. National- vs. Service-level Storage Space . 23 Nuclear Weapons Transport . 25 d. Implications for U.S. Policy . 27 Transport, Dismantlement and Storage . 27 Security of Warheads in Storages . 28 Fissile Material Container Storage . 29 Transparency . 30 Openness . 30 Appendix A: Dates and Pace of Warhead Withdrawals and Reductions . 34 1. Eastern Europe . 35 2. The Soviet Republics . 39 3. Ukraine, Kazakhstan and Belarus . 43 a. Tactical Weapons . 43 b. Strategic Weapons . 45 (1) Ukraine . 47 (2) Kazakhstan . 49 (3) Belarus . 51 4. Russia . 52 a. Tactical Weapons . 56 b. Strategic Weapons . 59 Appendix B: Stockpile Sizes and Numbers of Warheads Withdrawn . 60 1. Overall Nuclear Weapons Stockpile Estimates . 60 a. Russian information . 60 b. U.S. estimates . 61 2. Numbers of Warheads Consolidated into Russian Storages . 65 a. Overall Estimates of Strategic and Tactical Warheads Returned to Russia . 65 .1 b.