REVIEWS (Composite) REVIEWS (Composite).Qxd 08/09/2020 13:53 Page 90

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of Borderland Research V35 N4 Jul-Aug 1979

VOLUME XXXV, No. 4 Round Robin JULY-AUG 1979 The ck;i, r-:m <©f 1 r........... ;■ 1 ' ' TABLE OF CONTENTS 'THE CLONES OF ENKI By J»R» Jochmans. ......... 1 - 7 THE CLONES FROM GUTER SPACE By Dr. J. Hurtak. ........ 8-10 "WHAT ARE LITTLE ' FIT OF?” By loben: J ■_ h 1 : * . ti Trek. .11 - 13 POWER BEYOND YOUR FONDEST DREAMS By the Yada di Shi’ite. ....... 14 THE DRONES OF THE UNDERGROUND CITY By Ted n . ... 15 - 17 THE KAHUNA MAGICK OF HAWAII From a 1948 Round Robin ..... 18 - 19 RADI» TICS, A TAG 'M n .JN, Part III From Tom Bearden*s "Specula" and from Albert Bender*s "Flying Saucers and the Three Men". ........... 20 - 22 CLIPS, QUOTES & COMMENTS Did a Negative Thought Boomerang?, No There Is No Easy Way To Work the Cabala, The Church and I’.s Fi ■- loctrines, The Importance of Choosing the Right Parents, Saucer Wit Rides Again, Turn To Oux mj i -be Sim For Power, What’s This Polar Flip Business?, California*s Environmental Pointion Agency, Into the Valley Of Shadow and Out Again, The Higher Fifth State Of Consciousness, Measuring tl - ->-ain Herais- pheres, The Mind b.;:: ’ USPA Confer- fence, Can 5X Of the Population Save Us?, Dr. Decker Just Sud<m : oped Over, The U.S. Air Force Stymied By . ■ .lians Again, No Un- holy Alliance With Orica’:- ” m.' , God Will Never Liir i- Us, No More World War'Again, and BSRF Literature ....... 23 - 36 THE JOURNAL OF BORDERLAND RESEARCH BSRF No. 1 Published by Borderland Sciences Research Foundation, Inc-, PO Box 548, Vista, California 92083 USA. -

The London School of Economics and Political Science Making EU

The London School of Economics and Political Science Making EU Foreign Policy towards a ‘Pariah’ State: Consensus on Sanctions in EU Foreign Policy towards Myanmar Arthur Minsat A thesis submitted to the Department of International Relations of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, June 2012 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of the author. I warrant that this authorization does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 97,547 words. Statement of use of third party for editorial help I can confirm that my thesis was copy edited for conventions of language, spelling and grammar by Dr. Joe Hoover. 2 Abstract This thesis seeks to explain why the European Union ratcheted up restrictive measures on Myanmar from 1991 until 2010, despite divergent interests of EU member states and the apparent inability of sanctions to quickly achieve the primary objectives of EU policy. This empirical puzzle applies the ‘sanctions paradox’ to the issue of joint action in the EU. -

Apprentice Strikes in Twentieth Century UK Engineering and Shipbuilding*

Apprentice strikes in twentieth century UK engineering and shipbuilding* Paul Ryan Management Centre King’s College London November 2004 * Earlier versions of this paper were presented to the International Conference on the European History of Vocational Education and Training, University of Florence, the ESRC Seminar on Historical Developments, Aims and Values of VET, University of Westminster, and the annual conference of the British Universities Industrial Relations Association. I would like to thank Alan McKinlay and David Lyddon for their generous assistance, and Lucy Delap, Alan MacFarlane, Brian Peat, David Raffe, Alistair Reid and Keith Snell for comments and suggestions; the Engineering Employers’ Federation and the Department of Education and Skills for access to unpublished information; the staff of the Modern Records Centre, Warwick, the Mitchell Library, Glasgow, the Caird Library, Greenwich, and the Public Record Office, Kew, for assistance with archive materials; and the Nuffield Foundation and King’s College, Cambridge for financial support. 2 Abstract Between 1910 and 1970, apprentices in the engineering and shipbuilding industries launched nine strike movements, concentrated in Scotland and Lancashire. On average, the disputes lasted for more than five weeks, drawing in more than 15,000 young people for nearly two weeks apiece. Although the disputes were in essence unofficial, they complemented sector-wide negotiations by union officials. Two interpretations are considered: a political-social-cultural one, emphasising political motivation and youth socialisation, and an economics-industrial relations one, emphasising collective action and conflicting economic interests. Both interpretations prove relevant, with qualified priority to the economics-IR one. The apprentices’ actions influenced economic outcomes, including pay structures and training incentives, and thereby contributed to the decline of apprenticeship. -

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

Download (515Kb)

European Community No. 26/1984 July 10, 1984 Contact: Ella Krucoff (202) 862-9540 THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT: 1984 ELECTION RESULTS :The newly elected European Parliament - the second to be chosen directly by European voters -- began its five-year term last month with an inaugural session in Strasbourg~ France. The Parliament elected Pierre Pflimlin, a French Christian Democrat, as its new president. Pflimlin, a parliamentarian since 1979, is a former Prime Minister of France and ex-mayor of Strasbourg. Be succeeds Pieter Dankert, a Dutch Socialist, who came in second in the presidential vote this time around. The new assembly quickly exercised one of its major powers -- final say over the European Community budget -- by blocking payment of a L983 budget rebate to the United Kingdom. The rebate had been approved by Community leaders as part of an overall plan to resolve the E.C.'s financial problems. The Parliament froze the rebate after the U.K. opposed a plan for covering a 1984 budget shortfall during a July Council of Ministers meeting. The issue will be discussed again in September by E.C. institutions. Garret FitzGerald, Prime Minister of Ireland, outlined for the Parliament the goals of Ireland's six-month presidency of the E.C. Council. Be urged the representatives to continue working for a more unified Europe in which "free movement of people and goods" is a reality, and he called for more "intensified common action" to fight unemployment. Be said European politicians must work to bolster the public's faith in the E.C., noting that budget problems and inter-governmental "wrangles" have overshadolted the Community's benefits. -

Heroes of Peace Profiles of the Scottish Peace Campaigners Who Opposed the First World War

Heroes of Peace Profiles of the Scottish peace campaigners who opposed the First World War a paper from the Introduction The coming year will see many attempts to interpret the First World War as a ‘just’ war with the emphasis on the heroic sacrifice of troops in the face of an evil enemy. No-one is questioning the bravery or the sacrifice although the introduction of conscription sixteen months after the start of the war meant that many of the men who fought did not do so from choice and once in the armed forces they had to obey orders or be shot. Even many of the volunteers in the early stages of the war signed up on the assumption that it would all be over in a few months with few casualties. We want to ensure that there is an alternative – and we believe more valid – interpretation of the events of a century ago made available to the public. This was a war in which around ten million young men were killed on the battlefield in four years, about 120,000 of them were Scottish. Proportionately Scotland suffered the highest number of war dead apart from Serbia and Turkey. It was described as the ‘war to end wars’ but instead it created the conditions for the rise of Hitler and the Second World War just twenty years later as a result of the very harsh terms imposed on Germany and the determination to humiliate the losing states. It also contributed to some of the current problems in the Middle East since, as part of the war settlement, Britain and France took ownership of large parts of the Ottoman Empire and divided up the territory with no reference to the identities and interests of the people. -

We Can Be Heroes Just for One Day

ASLEFJOURNAL SEPTEMBER 2019 The magazine of the Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers & Firemen We can be heroes just for one day Standing by the wall I will be king & you, you will be queen And the guns shot above our heads For ever and ever And the shame was on the other side. We can beat them... The train drivers ’ Inside: Palestine; Pride; Michael Green; and Tolpuddle 2019 union since 1880 GS Mick Whelan ASLEFJOURNAL SEPTEMBER 2019 Chaos and confusion The magazine of the Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers & Firemen E HAVE never been in the W game of having preferences in contractual negotiations for franchises, even having different standards of Mick: ‘It’s the old cap industrial relations and collar process’ within certain groups. Our issue is, and always has been, with the model. Never has this been clearer than now, when we might have expected 10 a period of calm after Mr Grayling going and Mr 12 Shapps taking over. Alas, that is not the case. Confusion reigns. News The number of questions we have had over what has been announced continues to grow. l Rail fares rise again; and steam train blues 4 Apparently, Southeastern is to be run again as l Railway Workers’ Centenary Service; and 5 the conditions aren’t right; Stagecoach and Arriva Off the Rails: Patrick Flanery; Bev Quist; can take legal action over being excluded. Then Kim Darroch; and Christopher Meyer First Trenitalia wins the former Virgin bid because it meets Williams – a report we have not yet had – Cyril Power’s Tube train pictures on show 6 l and contains element of the old cap and collar l Kevin Lindsay hails a victory in Scotland 7 process that means the franchisee cannot lose. -

Dependent Origination: Seeing the Dharma

Dependent Origination: Seeing the Dharma Week Six: Interconnectedness and Interpenetration Experiential Homework Possibilities The experiential homework is essentially the first exercise we practiced in class involving looking for the boundary between oneself and other than self while experiencing seeing. This is the exercise my dissertation subjects were given for my data collection portion of my dissertation research. It relates directly to the transition from the link of nama-rupa to the link of vinnana, and then sankhara, that I spoke about in my talk this week. Just so that you can begin to have some experiential relationship to my research before I present my dissertation in our last session in two weeks, I’m including the exact instructions as they were given to my participants as well as the daily journal questionnaire they were asked to fill out. Exercises like these are meant not as onetime exercises but for repeated application. Your experience of them will often change and deepen if they are applied regularly over an extended period of time. My subjects used this exercise as part of their daily meditation practice for 15 minutes a day over a period of 10 days. Each day they filled out the questionnaire, their answers to which then became a significant part of my data. See below. Suggested Reading “Subtle Energy” This reading is a selection of excerpts from my dissertation Literature Review regarding the topic of subtle energy. See below. Transcendental Dependent Origination by Bhikkhu Bodhi. This is a sutta selection translated by Bhikkhu Bodhi with his commentary. While the ordinary form of Dependent Origination describes the causes and conditions that lead to suffering, in this version, the Buddha also enumerates the chain of causes and conditions that lead to the end of suffering. -

SLR I15 March April 03.Indd

scottishleftreview comment Issue 15 March/April 2003 A journal of the left in Scotland brought about since the formation of the t is one of those questions that the partial-democrats Scottish Parliament in July 1999 Imock, but it has never been more crucial; what is your vote for? Too much of our political culture in Britain Contents (although this is changing in Scotland) still sees a vote Comment ...............................................................2 as a weapon of last resort. Democracy, for the partial- democrat, is about giving legitimacy to what was going Vote for us ..............................................................4 to happen anyway. If what was going to happen anyway becomes just too much for the public to stomach (or if Bill Butler, Linda Fabiani, Donald Gorrie, Tommy Sheridan, they just tire of the incumbents or, on a rare occasion, Robin Harper are actually enthusiastic about an alternative choice) then End of the affair .....................................................8 they can invoke their right of veto and bring in the next lot. Tommy Sheppard, Dorothy Grace Elder And then it is back to business as before. Three million uses for a second vote ..................11 Blair is the partial-democrat par excellence. There are David Miller two ways in which this is easily recognisable. The first, More parties, more choice?.................................14 and by far the most obvious, is the manner in which he Isobel Lindsay views international democracy. In Blair’s world view, the If voting changed anything...................................16 purpose of the United Nations is not to make a reasoned, debated, democratic decision but to give legitimacy to the Robin McAlpine actions of the powerful. -

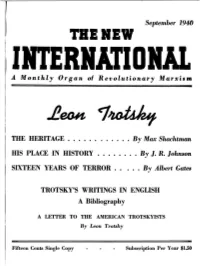

By Leon Trotsky

September 1940 TRIRI. A M on thl y Organ of Revolutionary M arxisrn THE HERITAGE .•••........ By Max Shachtman HIS PLACE IN HISTORY • • • • •.. By J. R. Johnson SIXTEEN YEARS OF TERROR . • . By Albert Gates TROTSKY'S WRITINGS IN ENGLISH A Bibliography A LETTER TO THE AMERICAN TROTSKYISTS By Leon Trotsky Fifteen Cents Single Copy Subscription Per Year $1.50 r THE NEW INTERNATIONAL ..4 Mon,hly Organ 01 Ref)olutionary Mar",lam Volume VI September, 1940 No.8 (Whole No. 47) Published ~onthly by NEW INTERNATIONAL Publishing Company, 114 West 14th Street, New York, N. Y. Telephone CHelsea 2·9681. One bit of good news this month is the fact that we have Subscription rates: $1.50 per year; bundles, 10c for 5 copies obtained second class mailing privileges for THE NEW INTER and up. Canada and foreign: $1.75 per year; bundles, 12c for 5 NATIONAL. This will help our program in the coming months. and up. Entered as second·class matter July 10, 1940, at the poet office at New York, N.Y. under the act of March 3, 1879. We succeeded in issuing a 32 page number in memory of Leon Trotsky, and we are going to try to continue with the larger Editor: MAX SHACHTMAN magazine. Business Manager: ALBERT GATES • TABLE OF CONTENTS The October issue is already in preparation. As we told you LEON TROTSKY: THE HERITAGE in August a special election would be published. We had orig By Max Shachtman ----------------------------------------- 147 inally planned this for September, but the tragic death of Trot TROTSKY'S PLACE IN HISTORY sky made necessary that postponement. -

Cromwellian Anger Was the Passage in 1650 of Repressive Friends'

Cromwelliana The Journal of 2003 'l'ho Crom\\'.Oll Alloooluthm CROMWELLIANA 2003 l'rcoklcnt: Dl' llAlUW CO\l(IA1© l"hD, t'Rl-llmS 1 Editor Jane A. Mills Vice l'l'csidcnts: Right HM Mlchncl l1'oe>t1 l'C Profcssot·JONN MOlUUU.., Dl,llll, F.13A, FlU-IistS Consultant Peter Gaunt Professor lVAN ROOTS, MA, l~S.A, FlU~listS Professor AUSTIN WOOLll'YCH. MA, Dlitt, FBA CONTENTS Professor BLAIR WORDEN, FBA PAT BARNES AGM Lecture 2003. TREWIN COPPLESTON, FRGS By Dr Barry Coward 2 Right Hon FRANK DOBSON, MF Chairman: Dr PETER GAUNT, PhD, FRHistS 350 Years On: Cromwell and the Long Parliament. Honorary Secretary: MICHAEL BYRD By Professor Blair Worden 16 5 Town Farm Close, Pinchbeck, near Spalding, Lincolnshire, PEl 1 3SG Learning the Ropes in 'His Own Fields': Cromwell's Early Sieges in the East Honorary Treasurer: DAVID SMITH Midlands. 3 Bowgrave Copse, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 2NL By Dr Peter Gaunt 27 THE CROMWELL ASSOCIATION was founded in 1935 by the late Rt Hon Writings and Sources VI. Durham University: 'A Pious and laudable work'. By Jane A Mills · Isaac Foot and others to commemorate Oliver Cromwell, the great Puritan 40 statesman, and to encourage the study of the history of his times, his achievements and influence. It is neither political nor sectarian, its aims being The Revolutionary Navy, 1648-1654. essentially historical. The Association seeks to advance its aims in a variety of By Professor Bernard Capp 47 ways, which have included: 'Ancient and Familiar Neighbours': England and Holland on the eve of the a. -

No. 181, November 11, 1977

WfJ/iIlE/iS ",IN(J(J,I/i, 25¢ No. 181 :-..==: )(,~:lJ 11 November 1977 ~-- - ~- -;' :;a. ~I"l,e~reAl. ' t~he·"arty,p. of I tile Russian Revolutioll • i 1 ,. f ~ • Sixtieth Anniversary of the ~ '!'--J t·1&~·- Bolshevik =' .~~~~I....... li.~'" E. ~ tt>c~~ t:~~~~ 1!!1.~ Oust tile Stalirlist Revolution ·~~.· ""I~,~. Bureaucracy! G ,j"§"!ill~'I\i.~.-'1... '-... October! the mood of the moment. The Russian against "Soviet social-imperialism"; program is as valid as it was 40 years The 1917 October Revolution was the ago. One ofits most powerfulpresenta question has been and remains the shaping event of our century. The centrists salute Lenin while ignoring his question of the revolution. The Russian life-long struggle for an international tions is the speech, reprinted below, by seizure of state power 60 years ago by James P. CannonJounder ofAmerican Bolsheviks on November 7, 1917, once the revolutionary Russian proletariat, proletarian vanguard as the roadto new and for all, took the question of the Octobers; and the now-reformist S WP Trotskyism, to the New York branch of led by its Bolshevik vanguard, was a the Socialist Workers Party on 15 workers' revolution out of the realm of monumental advance toward world sloughs offdefense of the USSR as an abstraction and gave it flesh and blood impediment to its social-democratic October 1939. Cannon's speech was socialism. Even today-decades after originally reprinted in the February reality. the usurpation ofpolitical power in the appetites. Only the international Spar It was said once of a book-I think it tacist tendency-the legitimate political 1940 New International; we are repu USSR by the Stalinist bureaucratic blishing it from his book, The Struggle was Whitman's "Leaves of Grass" caste whose counterrevolutionary be continuators of Lenin's Bolsheviks and "who touches this book, touches a of Trotsky's Fourth lnternational for a Proletarian Party, which originally trayals block the international exten appeared in 1943.