The Present Exegetical Study of the Introductory Lines of the San Tzu Ching Hsün Ku Is Based on Three Texts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

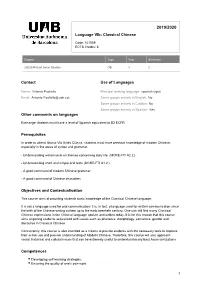

2015/2016 Language Vib: Classical Chinese

Language VIb: Classical Chinese 2015 - 2016 Language VIb: Classical Chinese 2015/2016 Code: 101559 ECTS Credits: 6 Degree Type Year Semester 2500244 East Asian Studies OB 3 2 Contact Use of languages Name: Anne Helene Suárez Girard Principal working language: spanish (spa) Email: [email protected] Some groups entirely in English: No Some groups entirely in Catalan: Yes Some groups entirely in Spanish: Yes Prerequisites The student must have previous knowledge of modern Chinese language, particularly concerning writing and syntax . Understand written texts on everyday topics . ( MCRE - FTI A2.2 . ) Produce written texts on everyday topics . ( MCRE - FTI A2.2 . ) Understand information from short oral texts. ( MCRE - FTI A1.2 . ) Produce short and simple oral texts. ( MCRE - FTI A1.2 . ) Objectives and Contextualisation The function of Xinès VIB: Xinès Clàssic is to provide students the basic knowledge of classical Chinese Language Studies. It is not a language intended for oral communication, but reserved the written since the beginning of Chinese writing Chinese literature until the early twentieth century communication. Even today many expressions and constructions are usual in modern llengua-oral or written-from the classical language. Therefore, this course aims to provide students with knowledge of Fonètica structures morphologically, semantics, gender and discourse in classical Chinese Language Studies. At the same time, Xinès VIB: Xinès Clàssic is designed to provide students with important knowledge to enhance their understanding and use of modern Chinese Language Studies, as well as those already mentioned, are other character socio-historical-cultural they can be extremely useful for understanding many of the cultures of East Asia. -

Journal Abbreviations

256 Journal Abbreviations AM: Asia Major AP: Asian Philosophy AS: Asiatische Studien / Études Asiatiques BIHP: Bulletin of the Institute of History and Philology (Academia Sinica) BMFEA: Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities BSOAS: Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies EC: Early China HJAS: Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies JAAR: Journal of the American Academy of Religion JAOS: Journal of the American Oriental Society JAS: Journal of Asian Studies JBL: Journal of Biblical Literature JCP: Journal of Chinese Philosophy JCR: Journal of Chinese Religions JEAA: Journal of East Asian Archaeology JTS: Journal of Theological Studies MS: Monumenta Serica NT: Novum Testamentum NTS: New Testament Studies OE: Oriens Extremus PEW: Philosophy East and West TP: T’oung Pao WSP: Warring States Papers Frequently Cited Monographs and Series William H Baxter. A Handbook of Old Chinese Phonology. Mouton 1992 BD:MichaelLoewe.ABiographicalDictionaryoftheQin...Brill2000 BDAG: Frederick William Danker. A Greek-English Lexicon...1957; 3ed Chicago 2000 E Bruce Brooks and A Taeko Brooks. The Original Analects. Columbia 1998 CHAC: Michael Loewe et al (ed). Cambridge History of Early China. Cambridge 1999 Chye!nMu". !!!! . !!!!!!!!!!!!!! . 2ed Hong Kong 1956 ECT: Michael Loewe (ed). Early Chinese Texts. SSEC 1993 GSB: Gu#-shr# Bye"n !!!!!! 1926-1941 GSR: Bernhard Karlgren. Grammata Serica Recensa. BMFEA v29 (1957) 1-332 HK: [The Chinese University of Hong Kong ICS concordances] HY: [The Harvard-Yenching concordances] Bernhard Karlgren. [The appropriate gloss or translation in BMFEA] James Legge. [The appropriate volume of James Legge’s Chinese Classics or SBE series] Jv"ng Lya!ng-shu" !!!!!!. !!!!!!!!!!.3v!!!!1984 Ma# Gwo!-ha"n !!!!!!. -

Classical Chinese

2019/2020 Language VIb: Classical Chinese Code: 101559 ECTS Credits: 6 Degree Type Year Semester 2500244 East Asian Studies OB 3 2 Contact Use of Languages Name: Antonio Paoliello Principal working language: spanish (spa) Email: [email protected] Some groups entirely in English: No Some groups entirely in Catalan: No Some groups entirely in Spanish: Yes Other comments on languages Exchange students must have a level of Spanish equivalent to B2 ECFR. Prerequisites In order to attend Idioma VIb Xinès Clàssic, students must have previous knowledge of modern Chinese, especially in the areas of syntax and grammar. - Understanding written texts on themes concerning daily life. (MCRE-FTI A2.2.) - Understanding short and simple oral texts (MCRE-FTI A1.2.) - A good command of modern Chinese grammar - A good command of Chinese characters Objectives and Contextualisation This course aims at providing students basic knowledge of the Classical Chinese language. It is not a language used for oral communication; it is, in fact, a language used for written communication since the birth of the Chinese writing system up to the early twentieth century. One can still find many Classical Chinese expressions in the Chinese language spoken and written today. It is for this reason that this course aims at getting students acquainted with issues such as phonetics, morphology, semantics, gender and discourse in Classical Chinese. Concurrently, this course is also intended as a means to provide students with the necessary tools to improve their active use and passive understanding of Modern Chinese. Therefore, this course will also approach social, historical and cultural issues that can be extremely useful to understand many East Asian civilizations. -

Concise English-Chinese Chinese-English Dictionary Free

FREECONCISE ENGLISH-CHINESE CHINESE-ENGLISH DICTIONARY EBOOK Manser H. Martin | 696 pages | 01 Jan 2011 | Commercial Press,The,China | 9787100059459 | English, Chinese | China Excerpt from A Concise Chinese-English Dictionary for Lovers | Penguin Random House Canada Notable Chinese dictionariespast and present, include:. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Wikipedia list article. Dictionaries of Chinese. List of Concise English-Chinese Chinese-English Dictionary dictionaries. Categories : Chinese dictionaries Lists of reference books. Concise English- Chinese Chinese-English Dictionary categories: Articles with short description Short description is different from Wikidata. Namespaces Article Talk. Views Read Edit View history. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Download as PDF Printable version. Add links. First Chinese dictionary collated in single-sort alphabetical order of pinyin, John DeFrancis. A Chinese-English Dictionary. Herbert Allen Giles ' bestselling dictionary, 2nd ed. A Dictionary of the Chinese Language. A Syllabic Dictionary of the Chinese Language. Small Seal Script orthographic primer, Li Si 's language reform. Chinese Concise English-Chinese Chinese-English Dictionary English Dictionary. Popular modern general-purpose encyclopedic dictionary, 6 editions. Concise Dictionary of Spoken Chinese. Tetsuji Morohashi 's Chinese- Japanese character dictionary, 50, entries. Oldest extant Chinese dictionary, semantic field collationone of the Thirteen Classics. Yang Xiongfirst dictionary of Chinese regional varieties. Le Grand Ricci or Grand dictionnaire Ricci de la langue chinoise,". First orthography dictionary of the regular script. Grammata Serica Recensa. Great Dictionary of Modern Chinese Dialects. Compendium of dictionaries for 42 local varieties of Chinese. Zhang Yi 's supplement to the Erya. Rime dictionary expansion of Qieyunsource for reconstruction of Middle Chinese. -

Etymologische Notizen Zum Wortfeld" Lachen" Und" Weinen" Im

Behr, W (2009). Etymologische Notizen zum Wortfeld "lachen" und "weinen" im Altchinesischen. In: Nitschke, A; Stagl, J; Bauer, D R. Überraschendes Lachen, gefordertes Weinen: Gefühle und Prozesse, Kulturen und Epochen im Vergleich. Wien, Austria, 401-446. Postprint available at: http://www.zora.uzh.ch University of Zurich Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich. Zurich Open Repository and Archive http://www.zora.uzh.ch Originally published at: Nitschke, A; Stagl, J; Bauer, D R 2009. Überraschendes Lachen, gefordertes Weinen: Gefühle und Prozesse, Winterthurerstr. 190 Kulturen und Epochen im Vergleich. Wien, Austria, 401-446. CH-8057 Zurich http://www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2009 Etymologische Notizen zum Wortfeld "lachen" und "weinen" im Altchinesischen Behr, W Behr, W (2009). Etymologische Notizen zum Wortfeld "lachen" und "weinen" im Altchinesischen. In: Nitschke, A; Stagl, J; Bauer, D R. Überraschendes Lachen, gefordertes Weinen: Gefühle und Prozesse, Kulturen und Epochen im Vergleich. Wien, Austria, 401-446. Postprint available at: http://www.zora.uzh.ch Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich. http://www.zora.uzh.ch Originally published at: Nitschke, A; Stagl, J; Bauer, D R 2009. Überraschendes Lachen, gefordertes Weinen: Gefühle und Prozesse, Kulturen und Epochen im Vergleich. Wien, Austria, 401-446. Etymologische Notizen zum Wortfeld „lachen“ und „weinen“ im Altchinesischen* Wolfgang Behr 1. Einleitung Eines der hartnäckigsten Klischees über „das“ Chinesische seit den Anfängen der missionarslinguistischen Beschäftigung mit dieser Spra- che im Europa des 17. Jahrhunderts besagt, dass es seit unvordenkli- chen Zeiten morphologisch isolierend gewesen sei und zudem über Jahrtausende hinweg im Zustand einer geographischen splendid isolation in diachroner Stagnation verharrt habe. -

Baxter-Sagart Old Chinese Reconstruction, Version 1.1 (20 September 2014) William H

Baxter-Sagart Old Chinese reconstruction, version 1.1 (20 September 2014) William H. Baxter (⽩⼀平) and Laurent Sagart (沙加爾) order: by Grammatica serica recensa number The following table presents data for almost 5,000 items with Old Chinese reconstructions in the Baxter-Sagart system. Our reconstruction system and supporting arguments and evidence are presented in our book Old Chinese: a new reconstruction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014). The columns in the table are as follows: GSR the number (with leading zeroes) and letter of the item in Bernhard Karlgren’s Grammata serica recensa (GSR, 1957). Characters not included in GSR are assigned a number corresponding to their phonetic element, followed by a hyphen (e.g., 賭 dǔ ‘to wager’, 0045-, whose phonetic element is GSR 0045a); characters that cannot be assigned to any of the phonetics in GSR are assigned a code “0000-” (e.g., � biān ‘whip’, 0000-) and placed at the beginning of the list. A character may be absent from GSR for several reasons: (1) Karlgren generally excluded characters that did not occur in pre-Qín texts (as far as he knew), although he included some characters from Shuōwén jiězì 《說⽂解字》. (2) He also excluded characters that did occur in pre-Qín documents but had no descendants in the later standard script. (3) He also seems to have excluded characters used only as place names. zi character (traditional form) py standard pronunciation in pīnyīn romanization MC ASCII-friendly Middle Chinese (MC) transcription. This is a minor modification of the notation used in Baxter (1992); for details see Baxter & Sagart (2014:9–20). -

On Peking Archaisms by Hugh M. Stimson Abbreviations

MORE ON PEKING ARCHAISMS BY HUGH M. STIMSON ABBREVIATIONS ' Kg according to Bernhard Karlgren's orthography, as in his Etudes suv la Phonologie chinoise (Leiden, 1915-26); Analytic dictionary, Chinese and Sino-Japanese (Paris, ig23) ; Gramntata serica = Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities I2.I-q.y (I94o); Crammata serica recensa = BMFEA 29.1-332 Compendium of phonetics in Ancient and Archaic Chinese = BMFEA 26.211-367 (1954). MC Middle Chinese = Karlgren's 'Ancient Chinese'. OC Old Chinese = Karlgren's 'Archaic Chinese'. OM Old Mandarin. Pk Modern Standard Mandarin, based on the Peking dialect. ST Sino-Tibetan. BIBLIOGRAPHY C Matthew Chen, "The time dimension: contribution toward a theory of sound change", Project on linguistic analysis : Reports, Second Series, No. 12, CHI-CH63 (1971). CD Yuen Ren Chao and Lien Sheng Yang, Concise dictionary of spoken Chinese, Cambridge, Mass., 1947. D Paul Demiéville, "Archaïsmes de prononciation en chinois vul- gaire", T'oung Pao 40.I-59 (1950). DKJ Morohashi Tetsuji, Dai Kanwa Jiten, Tokyo, 1955-60. GSR Bernhard Karlgren, Grammata serica recensa = BMFEA 29.1-332 (1957). GY Chén Péng-nián, Qiu Yong, and others, Guang yùn, preface dated in accordance with 1008; in Zhou Zu-mò, Guang-yùn jiào-ben, Peking, 1960. HFC Bei-jing Dà-xué Zhong-guó Yu-yán Wén-xué-xì Yu-yán-xué Jiào-yán-shì, ed., Hàn-yu fäng-yán Ci-hui, Peking, 1964. Kd George A. Kennedy, "A study of the particle yen", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 60.1-22,193-207 (1940); citation from T. Y. Li, ed., Selected works of George A. -

Historical Linguistics

HISTORICAL LINGUISTICS NICHOLAS CLEAVELAND BODMAN I. INTRODUCTION The literature on Chinese historical linguistics is already very large, and indeed unti very recently at least, the history of the language and its writing system has been the major focus of attention for scholars writing on the Chinese language. These writings are now becoming more and more voluminous, and many of them deserve more than ever before to be characterized as having real linguistic value, in the modern sense of the term, whereas the earlier writings in this field pertain more to a traditional philological or sinological approach.1 The native Chinese tradition of phonological studies had, in particular, reached a high degree of sophistication during the Ch'ing dynasty. This discipline2 has in fact made a generally happy marriage with modern Western linguistics. In surveying the major developments from the time of the Second World War to the present, I shall attempt to cover the most important current trends in the fields of historical phonology, morphology and syntax in writings dealing with the history of the Chinese language only,3 excepting where I touch upon comparative linguistic studies which would relate Chinese to other linguistic groups. The many works of a purely philological or text-critical nature and those having to do with semantic problems are not dealt with here. Important and numerous as they are, historical studies of lexical items are not treated here unless they are significant in a broader way or deal with matters having some phonological, morphological, or syntactic import. Similarly, I have not attempted any coverage of the large and important 1 The most important studies of the past twenty-five years are listed alphabetically by author in the Selected Bibliography at the end of this chapter. -

Beyond Rhyme: the Development of the Digital Etymological Dictionary of Old Chinese and Examples of Its Use in Textual Analyses from the Western Zhou to the Tang

Beyond Rhyme: The Development of the Digital Etymological Dictionary of Old Chinese and Examples of its Use in Textual Analyses from the Western Zhou to the Tang Jeffrey R. Tharsen, University of Chicago Creel-Luce Conference April 23-25, 2010 I. Introduction and Methodology Chinese readers have known for millennia that the sounds of the language(s) of their forebears were different from their current pronounciations of the characters. Sound glosses (sh ēng xùn 聲訊) in early dictionaries like the Er ya 《爾雅》, Fang yan 《方言》 and Shuowen jiezi 《說文解字》 were the first attempts at transmitting the phonetic values of a graph, complemented in the Western Han 西漢 dynasty by the creation of the dú ruò 讀若 method and in the Eastern Han 東漢 by the fǎnqìe 反切 system to give the pronunciation of at least the initials and finals of a specific graph. Since then, a wide variety of methods have been developed to help give readers a rough approximation of how the original sounds and rhyme schemes in the text may have functioned, including the use of dú y īn 讀音 and yǔ yīn 語音. Most recently, the application of the Western phonological methodology for reconstruction of the sounds of extinct languages, in particular the concepts of the allofam (word family) and etonym (word root) as evidenced through related Sinitic languages and in concert with Chinese xiésh ēng 諧聲 series has become instrumental in the analysis of ancient Chinese phonetics. The methodology outlined in this study represents a logical next step in the development of tools which can be employed to help us understand the tapestry of sounds and how these ancient texts may have been read throughout their early history, by allowing any text to be parsed into its possible phonetic readings and then read, using the International Phonetic Alphabet, in what modern phonologists have reconstructed as most approximating the pronunciations of the Chinese language of various early time periods. -

Writing and Rewriting the Poetry

Writing and Rewriting the Poetry Edward L. Shaughnessy The University of Chicago 12 September 2009 Paper for “International Symposium on Excavated Manuscripts and the Interpretation of the Book of Odes,” The University of Chicago, 12 September 2009 Studies of the Shi jing or Classic of Poetry have long been primarily concerned with how to read the text (or how the text has been read by others), and many of these discussions have contributed greatly to Chinese notions of reading in general. However, there has been rather less attention to how the Poetry may have been written in the first place (or the second or third place). There are several individual poems in the two Ya 雅 sections that explicitly mention the “making” (zuo 作) of the poem within the poem itself, some of these also mentioning the maker by name,1 and there are a few other poems that address unique and identifiable historical events in ways that reflect their making.2 Some of the Song 頌 or Hymns also seem to derive from or comment on particular events at the royal or regional courts, suggesting perhaps that they would have been composed by the contemporary secretaries of the courts.3 However, the more than half of the poems in the Poetry collection that are identified as Feng 風 or Airs are almost all anonymous in their own right, even if later traditions have ascribed them to particular individuals or circumstances, and make little or no mention of any historical context. Other traditions describe these poems as originating among the common people, from whom court officials -

BULLETIN of the MUSEUM of FAR EASTERN ANTIQUITIES (BMFEA) Revised December, 2016. Prices Are Listed in Swedish Crowns, SEK

BULLETIN OF THE MUSEUM OF FAR EASTERN ANTIQUITIES (BMFEA) Revised December, 2016. Prices are listed in Swedish crowns, SEK. Payment by bank transfer. All available items can be ordered from [email protected] , fax: +46-8-5195 5755, www.varldskulturmuseerna.se/ostasiatiskamuseet/ All volumes and separates are paper bound as issued. Titles within parenthesis are no longer in print. Please note that while a complete volume may be sold out, separates might still be available, or vice versa. Subscriptions to the BMFEA are also welcome, currently at 425.00 AVAILABLE, SEK per annum, less VAT for customers outside the European Union. Confirmed subscribers receive an invoice each time a new issue is distributed. * * * BMFEA BACK LIST (BMFEA 1, 1929) The complete issue is sold out. Separates: ANDERSSON, J. G., Origin and Aims of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities.18 p, 2 pl. AVAILABLE, SEK 50:- (CHOU CHAO-HSIANG, Pottery of the Chou Dynasty. Ed. B. Karlgren, with notes by Andersson. 9 p, 7 pl, 20 rubbings). AVAILABLE, SEK 50:- BOUILLARD, G., Note succinte sur l'histoire du territoire de Peking et sur les diverses enceintes de cette ville. 21 p, 4 maps. AVAILABLE, SEK 50:- TING, V. K., Notes on the Language of the Chuang in N. Kuangsi. 4 p. AVAILABLE, SEK 50:- (ANDERSSON, J. G., On Symbolism in the Prehistoric Painted Ceramics of China. 5 p). SOLD OUT (RYDH, H., On Symbolism in Mortuary Ceramics. 50 p, 11 pl, 62 fig.) SOLD OUT ANDERSSON, J. G., Der Weg über die Steppen. 21 p, 1 pl, 2 col. maps, 4 text-fig. -

A Methodological Procedure for the Analysis of the Wenxian Covenant Texts

A METHODOLOGICAL PROCEDURE FOR THE ANALYSIS OF THE WENXIAN COVENANT TEXTS Crispin Williams, Dartmouth College Abstract This article introduces a systematic methodological procedure for the analysis of Chinese palaeographic materials, constructed in this instance for the analysis of the Wenxian covenant texts (Wnxiàn méngsh ᄵᗼᅩ). The covenant texts have been dated to the early fifth century BC and were produced in the state of Jin வ; both the script and language of the covenants present problems of interpretation. The article first briefly introduces the tablets, on which the texts were written, and gives an example of the most commonly found type of covenant. A number of key palaeographic terms used in the description of the methodological procedure are then defined and discussed. These include terms related to characters, their non-standard forms and the components of which they are constructed, as well as terminology associated with transcription. Following this, the methodological procedure adopted for the analysis of the Wenxian texts is set out. The article concludes with the observation that the procedure has proven generally successful in the analysis of the texts under consideration. It also suggests that such a procedure is transferable to the analysis of other palaeographic materials and that an understanding of this methodology can aid the appraisal of transcriptions and annotations of previously published excavated texts. 1. Introduction This article introduces a methodological procedure constructed for the analysis of the Wenxian covenant texts (Wnxiàn méngsh ᄵᗼᅩ), a set of excavated texts currently being prepared for publication.1 Dated to the early fifth century, the texts are usually categorized as examples of Warring States script.