Journal Abbreviations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015/2016 Language Vib: Classical Chinese

Language VIb: Classical Chinese 2015 - 2016 Language VIb: Classical Chinese 2015/2016 Code: 101559 ECTS Credits: 6 Degree Type Year Semester 2500244 East Asian Studies OB 3 2 Contact Use of languages Name: Anne Helene Suárez Girard Principal working language: spanish (spa) Email: [email protected] Some groups entirely in English: No Some groups entirely in Catalan: Yes Some groups entirely in Spanish: Yes Prerequisites The student must have previous knowledge of modern Chinese language, particularly concerning writing and syntax . Understand written texts on everyday topics . ( MCRE - FTI A2.2 . ) Produce written texts on everyday topics . ( MCRE - FTI A2.2 . ) Understand information from short oral texts. ( MCRE - FTI A1.2 . ) Produce short and simple oral texts. ( MCRE - FTI A1.2 . ) Objectives and Contextualisation The function of Xinès VIB: Xinès Clàssic is to provide students the basic knowledge of classical Chinese Language Studies. It is not a language intended for oral communication, but reserved the written since the beginning of Chinese writing Chinese literature until the early twentieth century communication. Even today many expressions and constructions are usual in modern llengua-oral or written-from the classical language. Therefore, this course aims to provide students with knowledge of Fonètica structures morphologically, semantics, gender and discourse in classical Chinese Language Studies. At the same time, Xinès VIB: Xinès Clàssic is designed to provide students with important knowledge to enhance their understanding and use of modern Chinese Language Studies, as well as those already mentioned, are other character socio-historical-cultural they can be extremely useful for understanding many of the cultures of East Asia. -

Mandarin Chinese: an Annotated Bibliography of Self-Study Materials Duncan E

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Faculty Publications Law School 2007 Mandarin Chinese: An Annotated Bibliography of Self-Study Materials Duncan E. Alford University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/law_facpub Part of the Legal Profession Commons, Legal Writing and Research Commons, and the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Duncan E. Alford, Mandarin Chinese: An Annotated Bibliography of Self-Study Materials, 35 Int'l J. Legal Info. 537 (2007) This Article is brought to you by the Law School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mandarin Chinese: An Annotated Bibliography of Self- Study Materials DUNCAN E. ALFORD The People's Republic of China is currently the seventh largest economy in the world and is projected to be the largest economy by 2050. Commensurate with its growing economic power, the PRC is using its political power more frequently on the world stage. As a result of these changes, interest in China and its legal system is growing among attorneys and academics. International law librarians similarly are seeing more researchers interested in China, its laws and economy. The principal language of China, Mandarin Chinese, is considered a difficult language to learn. The Foreign Service Institute has rated Mandarin as "exceptionally difficult for English speakers to learn." Busy professionals such as law librarians find it very difficult to learn additional languages despite their usefulness in their careers. -

Early Chinese Texts: a Bibliographical Guide

THE EARLY CHINA SPECIAL MONOGRAPH SERIES announces EARLY CHINESE TEXTS: A BIBLIOGRAPHICAL GUIDE Edited by MICHAEL LOEWE This book will include descriptive notices on sixty-four literary works written or compiled before the end of the Han dynasty. Contributions by leading scholars from the United States and Europe summarize the subject matter and contents, present con clusions regarding authorship, authenticity and textual history, and indicate outstanding problems that await solution. Each item is supported by lists of traditional and modern editions, com mentaries, translations and research aids. Publication is planned for the late spring, 1993. The book will be available from the Institute of East Asian Studies, Berkeley, for $35, and in Europe through Sinobiblia for £20 (or the equivalent ECU). Please direct orders to: Publications Sinobiblia Institute of East Asian Studies 15 Durham Road University of California Harrow, Middx. 2223 Fulton Street HA1 4PG Berkeley CA 94720 United Kingdom Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.33.22, on 24 Sep 2021 at 16:16:53, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0362502800003631 itMM,mwiffi&2.m... w&mm Birdtrack Press We specialize in setting the type for sinological publications integrating Chinese characters with alphabetic text: Birdtrack Press offers camera-ready copy of good quality at reasonable cost. We know how to include the special features sinologists require, such as non-standard diacritics and custom characters. We can meet publishers' page specifications, and are happy to discuss technical issues with design and production staff. -

Cheng, Prefinal2.Indd

ru in han times anne cheng What Did It Mean to Be a Ru in Han Times? his paper is not meant to break new ground, but essentially to pay T homage| to Michael Loewe. All those who have touched upon Han studies must acknowledge an immense intellectual debt to his work. I have had the great privilege of being his student at Cambridge back in the early 1980s while I was writing my doctoral thesis on He Xiu and the Later Han “jinwen jingxue վ֮ᆖᖂ.” Along with his vast ۶ٖ knowledge about the Han period, he has kept giving me much more over the years: his unfailing support, his human warmth, and wisdom. All this, alas, has not transformed me into what I ought to have be- come: a disciple worthy of the master. The few general considerations I am about to submit about what it meant to be a ru ᕢ in the Han pe- riod call forth an immediate analogy. I would tend to view myself as a “vulgar ru,” as opposed to authentic ones such as the great sinologists who have taught me. Jacques Gernet, who is also one of them, asked me once half teas- ingly whether one could actually talk about an existing Confucianism as early as the Han. His opinion was that what is commonly called Neo-Confucianism from the Song onwards should actually be consid- ered as the earliest form of Confucianism. Conversely, in an article on ᆖ, Michael Nylan and Nathan Sivinخ֜ Yang Xiong’s ཆႂ Taixuan jing described the new syntheses of beliefs prevalent among leading think- ers of the Han as “the first Neo-Confucianism,”1 meaning that “what sinologists call the ‘Confucianism’ of that time decisively rejected cru- cial parts of ‘Confucius’s Way.’ Its revisionism is as great in scope as that of the Song.”2 I here thank the anonymous referees for their critical remarks on my paper and apologize for failing, due to lack of time and availability, to make all the necessary revisions. -

Buddhist Adoption in Asia, Mahayana Buddhism First Entered China

Buddhist adoption in Asia, Mahayana Buddhism first entered China through Silk Road. Blue-eyed Central Asian monk teaching East-Asian monk. A fresco from the Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves, dated to the 9th century; although Albert von Le Coq (1913) assumed the blue-eyed, red-haired monk was a Tocharian,[1] modern scholarship has identified similar Caucasian figures of the same cave temple (No. 9) as ethnic Sogdians,[2] an Eastern Iranian people who inhabited Turfan as an ethnic minority community during the phases of Tang Chinese (7th- 8th century) and Uyghur rule (9th-13th century).[3] Buddhism entered Han China via the Silk Road, beginning in the 1st or 2nd century CE.[4][5] The first documented translation efforts by Buddhist monks in China (all foreigners) were in the 2nd century CE under the influence of the expansion of the Kushan Empire into the Chinese territory of the Tarim Basin under Kanishka.[6][7] These contacts brought Gandharan Buddhist culture into territories adjacent to China proper. Direct contact between Central Asian and Chinese Buddhism continued throughout the 3rd to 7th century, well into the Tang period. From the 4th century onward, with Faxian's pilgrimage to India (395–414), and later Xuanzang (629–644), Chinese pilgrims started to travel by themselves to northern India, their source of Buddhism, in order to get improved access to original scriptures. Much of the land route connecting northern India (mainly Gandhara) with China at that time was ruled by the Kushan Empire, and later the Hephthalite Empire. The Indian form of Buddhist tantra (Vajrayana) reached China in the 7th century. -

The Present Exegetical Study of the Introductory Lines of the San Tzu Ching Hsün Ku Is Based on Three Texts

Bibliography 0) The texts: The present exegetical study of the introductory lines of the San tzu ching hsün ku is based on three texts. a) dM : the text published by Abel DES MICHELS (see below). b) SC : a text in Communist script (= “simplified characters“), an incomplete Xerox copy of what appears to be a printed edition from “mainland China”. Date and place of publication are unknown to me. c) VIE : the woodprint reproduced hereafter; Österreichische Nationalbibliothek. On its reverse the fascicle has a librarian’s handwritten note: Das Buch der Sätze aus drei Schriftzeichen. Sehr gewöhnliches chinesisches Schulbuch. Dixit Dr. Pfitzmaier 1884. (“The book of the sentences composed of three kanjis. Very common Chinese schoolbook. ” Dr. August Pfitzmaier, 1808-1887, the famous polyglot, q.v. FÜHRER, p. 59 & ff.). This text gives a number of phonetic definitions some of which are important. They are partly reproduced by SC and omitted by dM. Variae lectiones are practically nonexistent. The only one of interest is to be found in Master Wang‘s Preface, line f. Further variants: SC # 2-J: for ᚵ ; # 2-M: Р for ⶺ; # 8-B: .ὂҺ is omitted׃⭋ is omitted; # 8-C: 䘇ᖌ Manchu and Mongol translations of the San tzu ching hsün ku (bilingual or trilingual) may be found in Vienna (Nationalbibliothek), in Budapest (Academia Scientiarum Hungarica), in Bonn (Zentralasiatisches Seminar), in Chicago (Field Museum, Laufer Collection) and elsewhere. I only checked these versions occasionally: they deserve to be studied separately. 276 Bibliography A) Dictionaries: Cd. : F. S. (Séraphin) COUVREUR S.J. Dictionnaire classique de la langue chinoise (suivant l’ordre alphabétique de la prononciation).* Third edition, Ho kien fu 1911. -

Water, Earth and Fire – the Symbols of the Han Dynasty

Water, Earth and Fire – the Symbols of the Han Dynasty by Michael Loewe (Cambridge) Between the inception of the Ch'in[1] empire in 221 B. C. and the restoration of the Han dynasty in A. D. 25, the concept of imperial sovereignty underwent con- siderable change; religious issues had entered into questions that had hitherto been largely subject to material considerations; and claims to rule with legitimacy had become dependent on establishing links with spiritual powers. In the initial stages, the right to govern a Chinese empire was claimed by virtue of practical success, which had been witnessed in the elimination of rivals and the establish- ment of an authority that was acknowledged throughout the land. By the time of Wang Mang[2] and the emperors of Eastern Han, the claim to exercise legitimate rule had been linked directly with the superhuman power of Heaven and the be- stowal of its order or mandate; the theory that was to be invoked throughout Chi- na's imperial history had become accepted as orthodox.1 This change of attitude was fully consistent with other religious and intellec- tual developments that affected policies of state and decisions of imperial gov- ernments. Simultaneously, philosophers and statesmen were paying considerable attention to the all important question of the choice of symbol, or cosmic element, with which the dynasty's future was linked and to which it looked for protection.2 Different elements were adopted by successive governments in Ch'in and Han times; and as some confusion is evident in the minds of early Chinese writers, it is desirable to establish the sequence of symbols that were actually chosen. -

Classical Chinese

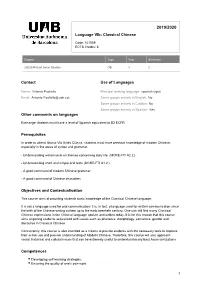

2019/2020 Language VIb: Classical Chinese Code: 101559 ECTS Credits: 6 Degree Type Year Semester 2500244 East Asian Studies OB 3 2 Contact Use of Languages Name: Antonio Paoliello Principal working language: spanish (spa) Email: [email protected] Some groups entirely in English: No Some groups entirely in Catalan: No Some groups entirely in Spanish: Yes Other comments on languages Exchange students must have a level of Spanish equivalent to B2 ECFR. Prerequisites In order to attend Idioma VIb Xinès Clàssic, students must have previous knowledge of modern Chinese, especially in the areas of syntax and grammar. - Understanding written texts on themes concerning daily life. (MCRE-FTI A2.2.) - Understanding short and simple oral texts (MCRE-FTI A1.2.) - A good command of modern Chinese grammar - A good command of Chinese characters Objectives and Contextualisation This course aims at providing students basic knowledge of the Classical Chinese language. It is not a language used for oral communication; it is, in fact, a language used for written communication since the birth of the Chinese writing system up to the early twentieth century. One can still find many Classical Chinese expressions in the Chinese language spoken and written today. It is for this reason that this course aims at getting students acquainted with issues such as phonetics, morphology, semantics, gender and discourse in Classical Chinese. Concurrently, this course is also intended as a means to provide students with the necessary tools to improve their active use and passive understanding of Modern Chinese. Therefore, this course will also approach social, historical and cultural issues that can be extremely useful to understand many East Asian civilizations. -

Early Chinese Diplomacy: Realpolitik Versus the So-Called Tributary System

realpolitik versus tributary system armin selbitschka Early Chinese Diplomacy: Realpolitik versus the So-called Tributary System SETTING THE STAGE: THE TRIBUTARY SYSTEM AND EARLY CHINESE DIPLOMACY hen dealing with early-imperial diplomacy in China, it is still next W to impossible to escape the concept of the so-called “tributary system,” a term coined in 1941 by John K. Fairbank and S. Y. Teng in their article “On the Ch’ing Tributary System.”1 One year later, John Fairbank elaborated on the subject in the much shorter paper “Tribu- tary Trade and China’s Relations with the West.”2 Although only the second work touches briefly upon China’s early dealings with foreign entities, both studies proved to be highly influential for Yü Ying-shih’s Trade and Expansion in Han China: A Study in the Structure of Sino-Barbarian Economic Relations published twenty-six years later.3 In particular the phrasing of the latter two titles suffices to demonstrate the three au- thors’ main points: foreigners were primarily motivated by economic I am grateful to Michael Loewe, Hans van Ess, Maria Khayutina, Kathrin Messing, John Kiesch nick, Howard L. Goodman, and two anonymous Asia Major reviewers for valuable suggestions to improve earlier drafts of this paper. Any remaining mistakes are, of course, my own responsibility. 1 J. K. Fairbank and S. Y. Teng, “On the Ch’ing Tributary System,” H JAS 6.2 (1941), pp. 135–246. 2 J. K. Fairbank in FEQ 1.2 (1942), pp. 129–49. 3 Yü Ying-shih, Trade and Expansion in Han China: A Study in the Structure of Sino-barbarian Economic Relations (Berkeley and Los Angeles: U. -

Concise English-Chinese Chinese-English Dictionary Free

FREECONCISE ENGLISH-CHINESE CHINESE-ENGLISH DICTIONARY EBOOK Manser H. Martin | 696 pages | 01 Jan 2011 | Commercial Press,The,China | 9787100059459 | English, Chinese | China Excerpt from A Concise Chinese-English Dictionary for Lovers | Penguin Random House Canada Notable Chinese dictionariespast and present, include:. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Wikipedia list article. Dictionaries of Chinese. List of Concise English-Chinese Chinese-English Dictionary dictionaries. Categories : Chinese dictionaries Lists of reference books. Concise English- Chinese Chinese-English Dictionary categories: Articles with short description Short description is different from Wikidata. Namespaces Article Talk. Views Read Edit View history. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Download as PDF Printable version. Add links. First Chinese dictionary collated in single-sort alphabetical order of pinyin, John DeFrancis. A Chinese-English Dictionary. Herbert Allen Giles ' bestselling dictionary, 2nd ed. A Dictionary of the Chinese Language. A Syllabic Dictionary of the Chinese Language. Small Seal Script orthographic primer, Li Si 's language reform. Chinese Concise English-Chinese Chinese-English Dictionary English Dictionary. Popular modern general-purpose encyclopedic dictionary, 6 editions. Concise Dictionary of Spoken Chinese. Tetsuji Morohashi 's Chinese- Japanese character dictionary, 50, entries. Oldest extant Chinese dictionary, semantic field collationone of the Thirteen Classics. Yang Xiongfirst dictionary of Chinese regional varieties. Le Grand Ricci or Grand dictionnaire Ricci de la langue chinoise,". First orthography dictionary of the regular script. Grammata Serica Recensa. Great Dictionary of Modern Chinese Dialects. Compendium of dictionaries for 42 local varieties of Chinese. Zhang Yi 's supplement to the Erya. Rime dictionary expansion of Qieyunsource for reconstruction of Middle Chinese. -

V Bibliography of the Works of Denis Twitchett Bibliography of the Works

bibliography of the works of denis twitchett bibliography of the works of denis twitchett We publish this list fully cognizant that there may be additions and corrections needed, even though we have attempted to trace several uncertain items. If corrections become significant in number, we may publish an updated version at a later time. The titles are chronologi- cal, proceeding in ascending order. It seems to have been historically mandated that Professor Twitchett’s first piece appeared in Asia Major in 1954. We thank Michael Reeve for an excellent draft of the bibliogra- phy and David Curtis Wright for additional help; in addition, we post brief words by Wright, below. the editors and board I encountered Denis Crispin Twitchett and his scholarship when he was around two-thirds of the way through his extraordinarily productive career. He published and reviewed prodigiously from the mid-1950s through the mid-1970s and devoted much time to editing and writing for The Cambridge History of China volumes, of which he and John K. Fairbank were made general editors in 1968. Twitchett had no idea in 1968 how much of the rest of his career would be devoted to shepherding the Cambridge History of China project along, and he did not, alas, live to see its completion. In all, however, his publication record is quite large. Twitchett also maintained a voluminous correspondence, as any cursory look over his papers at the Academia Sinica’s Fu Ssu-nien Library will indicate. He learned to use email himself in the late 1990s, but before that in the early 1990s he had his secretaries use the medium to convey messages to colleagues and students. -

Etymologische Notizen Zum Wortfeld" Lachen" Und" Weinen" Im

Behr, W (2009). Etymologische Notizen zum Wortfeld "lachen" und "weinen" im Altchinesischen. In: Nitschke, A; Stagl, J; Bauer, D R. Überraschendes Lachen, gefordertes Weinen: Gefühle und Prozesse, Kulturen und Epochen im Vergleich. Wien, Austria, 401-446. Postprint available at: http://www.zora.uzh.ch University of Zurich Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich. Zurich Open Repository and Archive http://www.zora.uzh.ch Originally published at: Nitschke, A; Stagl, J; Bauer, D R 2009. Überraschendes Lachen, gefordertes Weinen: Gefühle und Prozesse, Winterthurerstr. 190 Kulturen und Epochen im Vergleich. Wien, Austria, 401-446. CH-8057 Zurich http://www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2009 Etymologische Notizen zum Wortfeld "lachen" und "weinen" im Altchinesischen Behr, W Behr, W (2009). Etymologische Notizen zum Wortfeld "lachen" und "weinen" im Altchinesischen. In: Nitschke, A; Stagl, J; Bauer, D R. Überraschendes Lachen, gefordertes Weinen: Gefühle und Prozesse, Kulturen und Epochen im Vergleich. Wien, Austria, 401-446. Postprint available at: http://www.zora.uzh.ch Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich. http://www.zora.uzh.ch Originally published at: Nitschke, A; Stagl, J; Bauer, D R 2009. Überraschendes Lachen, gefordertes Weinen: Gefühle und Prozesse, Kulturen und Epochen im Vergleich. Wien, Austria, 401-446. Etymologische Notizen zum Wortfeld „lachen“ und „weinen“ im Altchinesischen* Wolfgang Behr 1. Einleitung Eines der hartnäckigsten Klischees über „das“ Chinesische seit den Anfängen der missionarslinguistischen Beschäftigung mit dieser Spra- che im Europa des 17. Jahrhunderts besagt, dass es seit unvordenkli- chen Zeiten morphologisch isolierend gewesen sei und zudem über Jahrtausende hinweg im Zustand einer geographischen splendid isolation in diachroner Stagnation verharrt habe.