Caspar Barlaeus – the Wise Merchant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018 Conforming to General Convention 2018 1 Preface Christians have since ancient times honored men and women whose lives represent heroic commitment to Christ and who have borne witness to their faith even at the cost of their lives. Such witnesses, by the grace of God, live in every age. The criteria used in the selection of those to be commemorated in the Episcopal Church are set out below and represent a growing consensus among provinces of the Anglican Communion also engaged in enriching their calendars. What we celebrate in the lives of the saints is the presence of Christ expressing itself in and through particular lives lived in the midst of specific historical circumstances. In the saints we are not dealing primarily with absolutes of perfection but human lives, in all their diversity, open to the motions of the Holy Spirit. Many a holy life, when carefully examined, will reveal flaws or the bias of a particular moment in history or ecclesial perspective. It should encourage us to realize that the saints, like us, are first and foremost redeemed sinners in whom the risen Christ’s words to St. Paul come to fulfillment, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” The “lesser feasts” provide opportunities for optional observance. They are not intended to replace the fundamental celebration of Sunday and major Holy Days. As the Standing Liturgical Commission and the General Convention add or delete names from the calendar, successive editions of this volume will be published, each edition bearing in the title the date of the General Convention to which it is a response. -

St. Augustine and the Doctrine of the Mystical Body of Christ Stanislaus J

ST. AUGUSTINE AND THE DOCTRINE OF THE MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST STANISLAUS J. GRABOWSKI, S.T.D., S.T.M. Catholic University of America N THE present article a study will be made of Saint Augustine's doc I trine of the Mystical Body of Christ. This subject is, as it will be later pointed out, timely and fruitful. It is of unutterable importance for the proper and full conception of the Church. This study may be conveniently divided into four parts: (I) A fuller consideration of the doctrine of the Mystical Body of Christ, as it is found in the works of the great Bishop of Hippo; (II) a brief study of that same doctrine, as it is found in the sources which the Saint utilized; (III) a scrutiny of the place that this doctrine holds in the whole system of his religious thought and of some of its peculiarities; (IV) some consideration of the influence that Saint Augustine exercised on the development of this particular doctrine in theologians and doctrinal systems. THE DOCTRINE St. Augustine gives utterance in many passages, as the occasion de mands, to words, expressions, and sentences from which we are able to infer that the Church of his time was a Church of sacramental rites and a hierarchical order. Further, writing especially against Donatism, he is led Xo portray the Church concretely in its historical, geographical, visible form, characterized by manifest traits through which she may be recognized and discerned from false chuiches. The aspect, however, of the concept of the Church which he cherished most fondly and which he never seems tired of teaching, repeating, emphasizing, and expound ing to his listeners is the Church considered as the Body of Christ.1 1 On St. -

Augustine and the Art of Ruling in the Carolingian Imperial Period

Augustine and the Art of Ruling in the Carolingian Imperial Period This volume is an investigation of how Augustine was received in the Carolingian period, and the elements of his thought which had an impact on Carolingian ideas of ‘state’, rulership and ethics. It focuses on Alcuin of York and Hincmar of Rheims, authors and political advisers to Charlemagne and to Charles the Bald, respectively. It examines how they used Augustinian political thought and ethics, as manifested in the De civitate Dei, to give more weight to their advice. A comparative approach sheds light on the differences between Charlemagne’s reign and that of his grandson. It scrutinizes Alcuin’s and Hincmar’s discussions of empire, rulership and the moral conduct of political agents during which both drew on the De civitate Dei, although each came away with a different understanding. By means of a philological–historical approach, the book offers a deeper reading and treats the Latin texts as political discourses defined by content and language. Sophia Moesch is currently an SNSF-funded postdoctoral fellow at the University of Oxford, working on a project entitled ‘Developing Principles of Good Govern- ance: Latin and Greek Political Advice during the Carolingian and Macedonian Reforms’. She completed her PhD in History at King’s College London. Augustine and the Art of Ruling in the Carolingian Imperial Period Political Discourse in Alcuin of York and Hincmar of Rheims Sophia Moesch First published 2020 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN and by Routledge 52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Published with the support of the Swiss National Science Foundation. -

Holland and the Rise of Political Economy in Seventeenth-Century Europe

Journal of Interdisciplinary History, xl:2 (Autumn, 2009), 215–238. ACCOUNTING FOR GOVERNMENT Jacob Soll Accounting for Government: Holland and the Rise of Political Economy in Seventeenth-Century Europe The Dutch may ascribe their present grandeur to the virtue and frugality of their ancestors as they please, but what made that contemptible spot of the earth so considerable among the powers of Europe has been their political wisdom in postponing everything to merchandise and navigation [and] the unlimited liberty of conscience enjoyed among them. —Bernard de Mandeville, The Fable of the Bees (1714) In the Instructions for the Dauphin (1665), Louis XIV set out a train- ing course for his son. Whereas humanists and great ministers had cited the ancients, Louis cited none. Ever focused on the royal moi, he described how he overcame the troubles of the civil war of the Fronde, noble power, and ªscal problems. This was a modern handbook for a new kind of politics. Notably, Louis exhorted his son never to trust a prime minister, except in questions of ªnance, for which kings needed experts. Sounding like a Dutch stadtholder, Louis explained, “I took the precaution of assigning Colbert . with the title of Intendant, a man in whom I had the highest conªdence, because I knew that he was very dedicated, intelli- gent, and honest; and I have entrusted him then with keeping the register of funds that I have described to you.”1 Jean-Baptiste-Colbert (1619–1683), who had a merchant background, wrote the sections of the Instructions that pertained to ªnance. He advised the young prince to master ªnance through the handling of account books and the “disposition of registers” Jacob Soll is Associate Professor of History, Rutgers University, Camden. -

The Intersection of Art and Ritual in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Visual Culture

Picturing Processions: The Intersection of Art and Ritual in Seventeenth-century Dutch Visual Culture By © 2017 Megan C. Blocksom Submitted to the graduate degree program in Art History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Chair: Dr. Linda Stone-Ferrier Dr. Marni Kessler Dr. Anne D. Hedeman Dr. Stephen Goddard Dr. Diane Fourny Date Defended: November 17, 2017 ii The dissertation committee for Megan C. Blocksom certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Picturing Processions: The Intersection of Art and Ritual in Seventeenth-century Dutch Visual Culture Chair: Dr. Linda Stone-Ferrier Date Approved: November 17, 2017 iii Abstract This study examines representations of religious and secular processions produced in the seventeenth-century Northern Netherlands. Scholars have long regarded representations of early modern processions as valuable sources of knowledge about the rich traditions of European festival culture and urban ceremony. While the literature on this topic is immense, images of processions produced in the seventeenth-century Northern Netherlands have received comparatively limited scholarly analysis. One of the reasons for this gap in the literature has to do with the prevailing perception that Dutch processions, particularly those of a religious nature, ceased to be meaningful following the adoption of Calvinism and the rise of secular authorities. This dissertation seeks to revise this misconception through a series of case studies that collectively represent the diverse and varied roles performed by processional images and the broad range of contexts in which they appeared. Chapter 1 examines Adriaen van Nieulandt’s large-scale painting of a leper procession, which initially had limited viewership in a board room of the Amsterdam Leprozenhuis, but ultimately reached a wide audience through the international dissemination of reproductions in multiple histories of the city. -

Sunday, July 18 9 A.M. – Baptism Class – Pope John

ST. CASPAR CHURCH WAUSEON, OHIO July 18, 2021 Monday, July 19 Nothing scheduled Sunday, July 18 Tuesday, July 20 – St. Apollinaris, Bishop & Martyr 9 a.m. – Baptism Class – Pope John Room 8:30 a.m. for religious vocations 11:30 a.m. – New Parishioner Registration – NW Wednesday, July 21 – St. Lawrence of Brindisi, Priest & Doctor 5 p.m. – Spanish Rosary – South Wing of the Church 8:30 a.m. for all leaders Monday, July 19 Thursday, July 22 – St. Mary Magdalene 7 p.m. – Prayer Group – South Wing 8:30 a.m. for the homeless Friday, July 23 Friday, July 23 – St. Bridget, Religious 6:30 p.m. – Encuentro – North Wing 8:30 a.m. Adolfo Ferriera (1 year) Saturday, July 24 Saturday, July 24 5 p.m. for families 6 p.m. – Rosary – South Wing Chapel Sunday, July 25 – Seventeenth Sunday in Ordinary Time 8 a.m. Lynn Keil Sunday, July 25 10:30 a.m. for St. Caspar parishioners 1 p.m. – Baptism – Church 1 p.m. for an end of abortion 5 p.m. – Spanish Rosary – South Wing Notre Dame Academy Seeks Host Families for Saturday, July 24– 5 p.m. International Students Arriving in August! Musicians: Proclaimer: Sally Kovar Do you want to learn more about another Servers: Ann Spieles & Brady Morr culture? Learn a new language, traditions, and food? Comm. Ministers: Roger & Cathy Drummer Then hosting an international student might be right Ushers: Team #1 (Jean LaFountain, Don Davis, Paul for you! Notre Dame Academy is seeking host Murphy) families for the 2021-22 school year. -

Bittersweet: Sugar, Slavery, and Science in Dutch Suriname

BITTERSWEET: SUGAR, SLAVERY, AND SCIENCE IN DUTCH SURINAME Elizabeth Sutton Pictures of sugar production in the Dutch colony of Suriname are well suited to shed light on the role images played in the parallel rise of empirical science, industrial technology, and modern capitalism. The accumulation of goods paralleled a desire to accumulate knowledge and to catalogue, organize, and visualize the world. This included possessing knowledge in imagery, as well as human and natural resources. This essay argues that representations of sugar production in eighteenth-century paintings and prints emphasized the potential for production and the systematization of mechanized production by picturing mills and labor as capital. DOI: 10.18277/makf.2015.13 ictures of sugar production in the Dutch colony of Suriname are well suited to shed light on the role images played in the parallel rise of empirical science, industrial technology, and modern capitalism.1 Images were important to legitimating and privileging these domains in Western society. The efficiency considered neces- Psary for maximal profit necessitated close attention to the science of agriculture and the processing of raw materials, in addition to the exploitation of labor. The accumulation of goods paralleled a desire to accumulate knowledge and to catalogue, organize, and visualize the world. Scientific rationalism and positivism corresponded with mercantile imperatives to create an epistemology that privileged knowledge about the natural world in order to control its resources. Prints of sugar production from the seventeenth century provided a prototype of representation that emphasized botanical description and practical diagrams of necessary apparatuses. This focus on the means of production was continued and condensed into representations of productive capacity and mechanical efficiency in later eighteenth-century images. -

* Diploma Lecture Series 2012 Absolutism to Enlightenment

Diploma Lecture Series 2012 Absolutism to enlightenment: European art and culture 1665-1765 Jan van Huysum: the rise and strange demise of the baroque flower piece Richard Beresford 21 / 22 March 2012 Introduction: At his death in 1749 Jan van Huysum was celebrated as the greatest of all flower painters. His biographer Jan van Gool stated that Van Huysum had ‘soared beyond all his predecessors and out of sight’. The pastellist Jean-Etienne Liotard regarded him as having perfected the oil painter’s art. Such was contemporary appreciation of his works that it is thought he was the best paid of any painter in Europe in the 18th century. Van Huysum’s reputation, however, was soon to decline. The Van Eyckian perfection of his technique would be dismissed by a generation learning to appreciate the aesthetic of impressionism. His artistic standing was then blighted by the onset of modernist taste. The 1920s and 30s saw his works removed from public display in public galleries, including both the Rijksmuseum and the Mauritshuis. The critic Just Havelaar was not the only one who wanted to ‘sweep all that flowery rubbish into the garbage’. Echoes of the same sentiment survive even today. It was not until 2006 that the artist received his first serious re-evaluation in the form of a major retrospective exhibition. If we wish to appreciate Van Huysum it is no good looking at his work through the filter an early 20th-century aesthetic prejudice. The purpose of this lecture is to place the artist’s achievement in its true cultural and artistic context. -

In This Week's Bulletin

CATHOLIC PARISH Diocese of Cleveland May 10, 2015 | Sixth Sunday of Easter IN THIS WEEK’S BULLETIN Parish Directory page 2 Women’s Guild Mother/Daughter Banquet Page 6 Loving God, Beyond We thank you for the love of the mothers you have given us, Driving with Dignity whose love is so precious that it can never be measured, Page 8 whose patience seems to have no end. May we see your loving hand behind them and guiding them. We pray for those mothers who fear they will run out of love or time or patience. We ask you to bless them with your own special love. We ask this in the name of Jesus, our brother. Amen. Saint Ambrose Catholic Parish | 929 Pearl Road, Brunswick, OH 44212 Phone | 330.460.7300 Fax |330.220.1748 Web | www.StAmbrose.us Sunday, May 10 | Mother’s Day THIS WEEK MARK YOUR CALENDARS 8:00 am-12:00 pm KofC Mother’s Day Breakfast (HH) 9:00-10:00 am Children’s Liturgy of the Word (CC) 10:30-11:30 am Children’s Liturgy of the Word (CC) 4:00-5:00 pm pm Cub Scouts (LCJN) Monday, May 11 May Crowning 9:00 am-5:00 pm Eucharistic Adoration (CC) Join Us! 6:00-8:00 pm Divorce Care for Kids (S) 6:00-8:00 pm Divorce Care (S) Tuesday | May 19, 2015 6:30-8:30 pm Scripture Study (LCMK) Time: 7:00pm 7:00-8:30 pm JH PSR Parent Meeting (LCJN) Procession to St. Ambrose Church 7:00-8:30 pm Youth & Young Adult Ministry (LCFM) Reception to follow in Hilkert Hall 7:00-9:00 pm Catholic Works of Mercy (LCMT) Tuesday, May 12 9:00-11:00 am Sarah’s Circle (LCMK) Saint Ambrose Directory 9:30 –11:30 am Ecumenical Women’s Breakfast (PCLMT) Here’s another 11:00 am-12:00 pm Music Ministry | New Life Choir (C) 6:00-8:00 pm CYO Volleyball (HHG) opportunity to have 7:00-8:00 pm Overeaters Anonymous (LCMT) your family picture 7:00-8:00 pm Worship Commission (HH) taken for our Parish 7:00-9:00 pm DBSA (LCJN) Directory! 7:00-9:00 pm Pastoral Council (PLCJP) 7:00-9:00 pm Knights of Columbus (LCFM) Photo Sessions will be held in the Lehner Center on: Wednesday, May 13 9:00-10:00 am Yoga (HH) Wednesday, May 13: 2-9pm 9:30-11:00 am Scripture Study (LCLK) Thursday, May 14: 2-9pm 1:00-2:00 pm Fr. -

The Dutch School of Painting

Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924073798336 CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 924 073 798 336 THE FINE-ART LIBRARY. EDITED BY JOHN C. L. SPARKES, Principal of the National Art Training School, South Kensington - Museum, THE Dutch School Painting. ye rl ENRY HA YARD. TRANSLATED HV G. POWELL. CASSELL & COMPANY, Limited: LONDON, PARIS, NEW YORK ,C- MELBOURNE. 1885. CONTENTS. -•o*— ClIAr. I'AGE I. Dutch Painting : Its Origin and Character . i II. The First Period i8 III. The Period of Transition 41 IV. The Grand Ki'ocii 61 V. Historical and Portrait Painters ... 68 VI. Painters of Genre, Interiors, Conversations, Societies, and Popular and Rustic Scenes . 117 VI [. Landscape Painters 190 VIII. Marine Painters 249 IX. Painters of Still Life 259 X. The Decline ... 274 The Dutch School of Painting. CHAPTER I. DUTCH PAINTING : ITS ORIGIN AND CHARACTER. The artistic energy of a great nation is not a mere accident, of which we can neither determine the cause nor foresee the result. It is, on the contrary, the resultant of the genius and character of the people ; the reflection of the social conditions under which it was called into being ; and the product of the civilisation to which it owes its birth. All the force and activity of a race appear to be concentrated in its Art ; enterprise aids its growth ; appreciation ensures its development ; and as Art is always grandest when national prosperity is at its height, so it is pre-eminently by its Art that we can estimate the capabilities of a people. -

The Vanitas in the Works of Maria Van Oosterwijck & Marian Drew

The Vanitas In The Works Of Maria Van Oosterwijck & Marian Drew Both Maria Van Oosterwijck and Marian Drew have produced work that has been described as the Vanitas. Drew does so as a conscious reference to the historic Dutch genre, bringing it into a contemporary Australian context. Conversely, Van Oosterwijck was actively embedded in the original Vanitas still-life movement as it was developed in 17th century Netherlands. An exploration into the works of Maria Van Oosterwijck and Marian Drew will compare differences in their communication of the Vanitas, due to variations in time periods, geographic context, intended audience and medium. Born in 1630, Maria Van Oosterwijck was a Dutch still-life painter. The daughter of a protestant preacher, she studied under renowned still-life painter Jan Davidsz de Heem from a young age, but Quickly developed an independent style. Her work was highly sort after amongst the European bourgeoisie, and sold to monarchs including Queen Mary, Emperor Leopold and King Louis XIV. Van Oosterwijck painted in the Vanitas genre, and was heavily influenced by Caravaggio’s intense chiaroscuro techniQue, as well as the trompe l’oiel realism popular in most Northern BaroQue painting (Vigué 2003). Marian Drew is a contemporary Australian photographic artist. She is known for her experimentations within the field of photography, notably the light painting techniQue she employs to create a deep chiaroscuro effect. This techniQue also produces an almost painterly effect in the final images, which she prints onto large- scale cotton paper. In Drew’s Australiana/Still Life series, she photographed native road kill next to household items and flora, in the style of Dutch Vanitas and game- painting genres. -

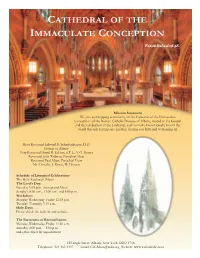

Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception

CATHEDRAL OF THE IMMACULATE CONCEPTION Established 1848 Mission Statement We, the worshipping community of the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Albany, rooted in the Gospel and the celebration of the Eucharist, seek to make known God’s love in the world through serving one another, sharing our faith and welcoming all. Most Reverend Edward B. Scharfenberger, D.D. Bishop of Albany Very Reverend David R. LeFort, S.T.L., V.G. Rector Reverend John Tallman, Parochial Vicar Reverend Paul Mijas, Parochial Vicar Mr. Timothy J. Kosto, II, Deacon Schedule of Liturgical Celebrations The Holy Eucharist (Mass) The Lord’s Day: Saturday 5:15 p.m. (anticipated Mass) Sunday’s 9:00 a.m., 11:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m. Weekdays: Monday-Wednesday-Friday 12:15 p.m. Tuesday-Thursday 7:15 a.m. Holy Days: Please check the bulletin and website. The Sacrament of Reconciliation: Monday-Wednesday-Friday 11:30 a.m. Saturday 4:00 p.m. – 5:00 p.m. and other times by appointment 125 Eagle Street Albany, New York 12202-1718 Telephone: 518-463-4447 Email: [email protected] Website: www.cathedralic.com CATHEDRAL OF THE IMMACULATE CONCEPTION ALBANY Solemnity of the Epiphany of the Lord On the Sunday of the Epiphany of the Lord, we hear about gifts in the gospel reading. The image of gift is an appropriate one since to- day, on Epiphany Sunday, we acknowledge and celebrate the gift of God’s saving grace offered to everyone in the birth of his Son Je- sus.