Bittersweet: Sugar, Slavery, and Science in Dutch Suriname

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Holland and the Rise of Political Economy in Seventeenth-Century Europe

Journal of Interdisciplinary History, xl:2 (Autumn, 2009), 215–238. ACCOUNTING FOR GOVERNMENT Jacob Soll Accounting for Government: Holland and the Rise of Political Economy in Seventeenth-Century Europe The Dutch may ascribe their present grandeur to the virtue and frugality of their ancestors as they please, but what made that contemptible spot of the earth so considerable among the powers of Europe has been their political wisdom in postponing everything to merchandise and navigation [and] the unlimited liberty of conscience enjoyed among them. —Bernard de Mandeville, The Fable of the Bees (1714) In the Instructions for the Dauphin (1665), Louis XIV set out a train- ing course for his son. Whereas humanists and great ministers had cited the ancients, Louis cited none. Ever focused on the royal moi, he described how he overcame the troubles of the civil war of the Fronde, noble power, and ªscal problems. This was a modern handbook for a new kind of politics. Notably, Louis exhorted his son never to trust a prime minister, except in questions of ªnance, for which kings needed experts. Sounding like a Dutch stadtholder, Louis explained, “I took the precaution of assigning Colbert . with the title of Intendant, a man in whom I had the highest conªdence, because I knew that he was very dedicated, intelli- gent, and honest; and I have entrusted him then with keeping the register of funds that I have described to you.”1 Jean-Baptiste-Colbert (1619–1683), who had a merchant background, wrote the sections of the Instructions that pertained to ªnance. He advised the young prince to master ªnance through the handling of account books and the “disposition of registers” Jacob Soll is Associate Professor of History, Rutgers University, Camden. -

The Intersection of Art and Ritual in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Visual Culture

Picturing Processions: The Intersection of Art and Ritual in Seventeenth-century Dutch Visual Culture By © 2017 Megan C. Blocksom Submitted to the graduate degree program in Art History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Chair: Dr. Linda Stone-Ferrier Dr. Marni Kessler Dr. Anne D. Hedeman Dr. Stephen Goddard Dr. Diane Fourny Date Defended: November 17, 2017 ii The dissertation committee for Megan C. Blocksom certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Picturing Processions: The Intersection of Art and Ritual in Seventeenth-century Dutch Visual Culture Chair: Dr. Linda Stone-Ferrier Date Approved: November 17, 2017 iii Abstract This study examines representations of religious and secular processions produced in the seventeenth-century Northern Netherlands. Scholars have long regarded representations of early modern processions as valuable sources of knowledge about the rich traditions of European festival culture and urban ceremony. While the literature on this topic is immense, images of processions produced in the seventeenth-century Northern Netherlands have received comparatively limited scholarly analysis. One of the reasons for this gap in the literature has to do with the prevailing perception that Dutch processions, particularly those of a religious nature, ceased to be meaningful following the adoption of Calvinism and the rise of secular authorities. This dissertation seeks to revise this misconception through a series of case studies that collectively represent the diverse and varied roles performed by processional images and the broad range of contexts in which they appeared. Chapter 1 examines Adriaen van Nieulandt’s large-scale painting of a leper procession, which initially had limited viewership in a board room of the Amsterdam Leprozenhuis, but ultimately reached a wide audience through the international dissemination of reproductions in multiple histories of the city. -

Download PDF Van Tekst

OSO. Tijdschrift voor Surinaamse taalkunde, letterkunde en geschiedenis. Jaargang 12 bron OSO. Tijdschrift voor Surinaamse taalkunde, letterkunde en geschiedenis. Jaargang 12. Stichting Instituut ter Bevordering van de Surinamistiek, [Nijmegen] 1993 Zie voor verantwoording: https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_oso001199301_01/colofon.php Let op: werken die korter dan 140 jaar geleden verschenen zijn, kunnen auteursrechtelijk beschermd zijn. Afbeeldingen omslag De afbeelding op de voorzijde van de omslag is een tekening van het huis Zeelandia 7, afkomstig uit C.L. Temminck Grol, De architektuur van Suriname, 1667-1930. Zutphen: Walburg Pers, 1973. Op de achterkant is de bekende lukuman Quassie geportretteerd naar de gravure van William Blake in Stedman's Narrative of a Five Years Expedition Against the Revolted Negroes in Surinam (1796). In dit nummer van OSO is een artikel over Quassie opgenomen. OSO. Tijdschrift voor Surinaamse taalkunde, letterkunde en geschiedenis. Jaargang 12 1 OSO tijdschrift voor Surinaamse taalkunde letterkunde, cultuur en geschiedenis Inhoudsopgave en index Jaargang 6-11 (1987-1992) Artikelen Agerkop, Terry 1989 Orale tradities: een inleiding, 8 (2): 135-136. Arends, Jacques 1987 De historische ontwikkeling van de comparatiefconstructie in het Sranan als ‘post-creolisering’, 8 (2): 201-217. Baldewsingh, R. 1989 Orale literatuur van de Hindostanen, 8 (2): 167-170. Beeldsnijder, Ruud 1991 Op de onderste trede. Over vrije negers en arme blanken in Suriname 1730-1750, 10 (1): 7-30. Beet, Chris de 1992 Een staat in een staat: Een vergelijking tussen de Surinaamse en Jamaicaanse Marrons, 11 (2): 186-193. Bies, Renate de 1990 Woordenboek van het Surinaams-Nederlands: Woordenboek of inventaris? (discussie), 9 (1): 85-87. -

Estudos Botânicos No Brasil Nassoviano: O Herbário De Marcgrave E Suas Contribuições Para a Difusão Do Conhecimento

ESTUDOS BOTÂNICOS NO BRASIL NASSOVIANO: O HERBÁRIO DE MARCGRAVE E SUAS CONTRIBUIÇÕES PARA A DIFUSÃO DO CONHECIMENTO Botanical studies in Nassovian Brazil: Marcgrave's herbarium and its contributions to the dissemination of knowledge Bárbara Martins Lopes1 Roniere dos Santos Fenner2 Maria do Rocio Fontoura Teixeira3 Resumo: O presente artigo pretende revisitar o contexto histórico dos estudos botânicos, no período holandês, no século XVII, em Pernambuco, feitos especialmente por George Marcgrave, e a importância do herbário de sua autoria. Como procedimentos metodológicos, utilizou-se a pesquisa descritiva e documental, com coleta de dados a partir da documentação do acervo da Biblioteca do Instituto Ricardo Brennand, da coleção da Revista do Instituto Arqueológico e Histórico de Pernambuco, da Revista do Museu Paulista, da Biblioteca Digital de Teses e Dissertações da Capes, do Google Acadêmico e do acervo da Academia Pernambucana de Ciência Agronômica. Os resultados levaram a refletir acerca da prática científica do botânico George Marcgrave, cujos estudos continuam importantes, com destaque para o herbário por ele organizado, pioneiro por se tratar da primeira coleção de objetos naturais com finalidade científica, bem como sua relevância para o ensino de ciências na atualidade. Palavras-chave: Estudos botânicos. Herbário. Ciência. Abstract: This article aims to revisit the historical context of botanical studies, in the Dutch period, in the 17th century, in Pernambuco, made especially by George Marcgrave, and the importance of herbarium. As methodological procedures, descriptive and documentary research was used, with data collection from the documentation of the Ricardo Brennand Institute Library, the collection of the Revista do Instituto Arqueológico e Histórico de Pernambuco, the Revista do Museu Paulista, the Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations by Capes, Google Scholar and the collection of the Pernambuco Academy of Agricultural Science. -

Itinerario Creating Confusion in the Colonies: Jews, Citizenship, and the Dutch and British Atlantics

Itinerario http://journals.cambridge.org/ITI Additional services for Itinerario: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Creating Confusion in the Colonies: Jews, Citizenship, and the Dutch and British Atlantics Jessica Roitman Itinerario / Volume 36 / Issue 02 / August 2012, pp 55 90 DOI: 10.1017/S0165115312000575, Published online: Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0165115312000575 How to cite this article: Jessica Roitman (2012). Creating Confusion in the Colonies: Jews, Citizenship, and the Dutch and British Atlantics. Itinerario, 36, pp 5590 doi:10.1017/S0165115312000575 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/ITI, IP address: 132.229.193.5 on 02 Nov 2012 55 Creating Confusion in the Colonies Jews, Citizenship, and the Dutch and British Atlantics JESSICA ROITMAN* Jews in most of early modern Europe struggled to assert their rights within legal frameworks that presumed them to be intrinsically different—aliens—from the (Christian) population around them no matter where they had been born, how they dressed and behaved, or what language they spoke. This struggle played itself out on various fronts, not the least of which was in the Jewish assertion of the right to become more than aliens—to become citizens or subjects—of the territories in which they lived. Citizenship, in its various forms, was a structural representation of belonging. Moreover, citizenship conferred tangible rights. As such, being a recog- nised citizen (or subject) had not only great symbolic, but also great economic, importance. This recognition of belonging was needed for, among other things, Jewish par- ticipation in the settlement and economic exploitation of the Dutch and British Atlantic overseas’ possessions. -

De Militair Geneeskundige Dienst Vroeger En Nu

De Militair Geneeskundige Dienst vroeger en nu door J. KARBAAT, Majoor-Arts, Commandant Afdeling Geneeskundige Dienst van de Troepenmacht in Suriname Waarom na de reeds verschenen hoofdstukken In de instructie van Crijnssen staat wel het over de Troepenmacht in Suriname, nu nog iets een en ander vermeld over de voeding, het over een bepaald onderdeel van de Troepen- drinkwater en de hygiëne van de soldaten en macht, zult u zich afvragen. Het antwoord hier- matrozen, maar niets over de geneeskundige op is niet zo moeilijk te geven. In de eerste verzorging. plaats neemt de MGD in de geschiedenis van Uit een sterkte-opgave van de Troepenmacht Suriname een zeer bijzonder plaats in, omdat het door kapitein P. Versterre in 1675 weten wij, dat Militair Hospitaal (dat qua instelling reeds gedu- er in dat jaar een chirurgijn, Meester Damaert, rende 200 jaar bestaat) gedurende bijna 100 bij de troepen aanwezig was. In 1679 is er een jaren de enige ziekeninrichting in Suriname was. opper-chirurgijn, een chirurgijn en bovendien Het pionierswerk op het gebied van curatieve en sedert 1678 een apotheker bij de troepen. Uit preventieve geneeskunde in Suriname is vooral een financiële verantwoording van gouverneur door militaire artsen verricht. In de tweede J. Heinsius in 1679 blijkt, dat hij 200 pond sui- plaats omdat ook nu nog de MGD in Suriname ker d.i. ƒ 20 per maand aan het ziekenhuis qua te verzorgen categorieën personen een veel betaalde voor geneeskundige hulp aan soldaten. uitgebreider arbeidsveld heeft dan de MGD in Hieruit blijkt dat er in dat jaar reeds een soort Nederland. -

Paramaribo As Dutch and Atlantic Nodal Point, 1650–1795

Paramaribo as Dutch and Atlantic Nodal Point, 1650–1795 Karwan Fatah-Black Introduction The Sociëteit van Suriname (Suriname Company, 1683–1795) aimed to turn Suriname into a plantation colony to produce tropical products for Dutch mer- chants, and simultaneously provide a market for finished products and stimu- late the shipping industry.1 To maximize profits for the Republic the charter of the colony banned merchants from outside the Republic from connecting to the colony’s markets. The strict mercantilist vision of the Dutch on how the tropical plantation colony should benefit the metropolis failed to materialize, and many non-Dutch traders serviced the colony’s markets.2 The significant breaches in the mercantilist plans of the Dutch signify the limits of metropoli- tan control over the colonial project. This chapter takes ship movements to and from Paramaribo as a very basic indication for breaches in the mercantilist plans of the Dutch: the more non- Dutch ships serviced Suriname relative to the number of Dutch ships, the less successful the Suriname Company was in realizing its “walled garden” concept of the colony. While Suriname had three European villages (Torarica, Jodensavanne and Paramaribo) in the seventeenth century, Paramaribo became its sole urban core in the eighteenth century. This centralization and * The research done for this chapter was first presented in a paper at the European Social Science and History Conference 2010 in Ghent and figures prominently in the PhD disserta- tion Suriname and the Atlantic World, 1650–1800 defended on 1 October 2013 at Leiden University. 1 Octroy ofte fondamentele conditien, onder de welcke haer Hoogh. -

Remnants of the Early Dutch in Guyana 1616-1815 Nova Zeelandia (New Zeeland

Remnants Of The Early Dutch in Guyana 1616-1815 By Dmitri Allicock Coat of arms -Flag of the Dutch West Indian Company- 1798 Map of Essequibo and Demerara Nova Zeelandia (New Zeeland} Guyana is the only English-speaking country in South America, but English has been the official language for less than half the time Europeans occupied the country. The Dutch language was the main medium of communication for 232 years, from the time a group of Dutchmen sailed up the Pomeroon River and settled there, to 1812 when English replaced Dutch as the language used in the Court of Policy (Parliament). To this day, hundreds of villages have retained their original Dutch names like Uitvlugt, Vergenoegen and Zeeburg. Some present-day Guyanese have names like Westmaas, Van Lange and Meertens. No Guyanese citizen or visitor can escape visible and other reminders of our Dutch predecessors. The ruins of a brick fort can still be seen on a little island where the Essequibo, Mazaruni and Cuyuni rivers meet. The original fort was a wooden structure built around 1600 by some Dutch traders who called it Kyk-over-al or "See-over-all" because it provided a commanding view of the three rivers. From 1627 the fort was controlled by the Dutch West India Company, a Holland-based organization which was vested with the power to establish colonies and which monopolized Dutch trade in the New World. The Company appointed Adrianetz Groenewegel as its first Commander to administer Kyk-over-al. The wooden fort was replaced in the 1630s by a brick structure which also served as an administrative centre. -

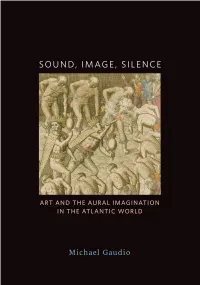

Sound, Image, Silence: Art and the Aural Imagination in the Atlantic World

Sound, Image, Silence Gaudio.indd 1 30/08/2019 10:48:14 AM Gaudio.indd 2 30/08/2019 10:48:16 AM Sound, Image, Silence Art and the Aural Imagination in the Atlantic World Michael Gaudio UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA PRESS MINNEAPOLIS • LONDON Gaudio.indd 3 30/08/2019 10:48:16 AM This book is freely available in an open access edition thanks to TOME (Toward an Open Monograph System)—a collaboration of the Association of American Universities, the Association of University Presses, and the Association of Research Libraries—and the generous support of the College of Liberal Arts at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities. Learn more at openmonographs.org. The publication of this book was supported by an Imagine Fund grant for the Arts, Design, and Humanities, an annual award from the University of Minnesota’s Provost Office. A different version of chapter 3 was previously published as “Magical Pictures, or, Observations on Lightning and Thunder, Occasion’d by a Portrait of Dr. Franklin,” in Picturing, ed. Rachael Ziady DeLue, Terra Foundation Essays 1 (Paris and Chicago: Terra Foundation for American Art, 2016; distributed by the University of Chicago Press). A different version of chapter 4 was previously published as “At the Mouth of the Cave: Listening to Thomas Cole’s Kaaterskill Falls,” Art History 33, no. 3 (June 2010): 448– 65. Copyright 2019 by the Regents of the University of Minnesota Sound, Image, Silence: Art and the Aural Imagination in the Atlantic World is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0): https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. -

Interpretative Ingredients: Formulating Art and Natural History in Early Modern Brazil

Interpretative ingredients: formulating art and natural history in early modern Brazil Amy Buono Introduction In this article I look at two early modern texts that pertain to the natural history of Brazil and its usage for medicinal purposes. These texts present an informative contrast in terms of information density and organization, raising important methodological considerations about the ways that inventories and catalogues become sources for colonial scholarship in general and art history in particular. Willem Piso and Georg Marcgraf’s Natural History of Brazil was first published in Latin by Franciscus Hackius in Leiden and Lodewijk Elzevir in Amsterdam in 1648. Known to scholars as the first published natural history of Brazil and a pioneering work on tropical medicine, this text was, like many early modern scientific projects, a collaborative endeavor and, in this particular case, a product of Prince Johan Maurits of Nassau’s Dutch colonial enterprise in northern Brazil between 1630-54. Authored by the Dutch physician Willem Piso and the German naturalist Georg Marcgraf, the book was edited by the Dutch geographer Joannes de Laet, produced under commission from Johan Maurits, and likely illustrated by the court painter Albert Eckhout, along with other unknown artists commissioned for the Maurits expedition.1 Its title page has become emblematic for art historians and historians of science alike as a pictorial entry point into the vast world of botanical, zoological, medicinal, astronomical, and ethnographic knowledge of seventeenth-century Brazil (Fig. 1). 2 Special thanks to Anne Helmreich and Francesco Freddolini for the invitation to contribute to this volume, as well as for their careful commentary. -

The West Indian Web Improvising Colonial Survival in Essequibo and Demerara, 1750-1800

The West Indian Web Improvising colonial survival in Essequibo and Demerara, 1750-1800 Bram Hoonhout Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Florence, 22 February 2017 European University Institute Department of History and Civilization The West Indian Web Improvising colonial survival in Essequibo and Demerara, 1750-1800 Bram Hoonhout Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Examining Board Prof. dr. Jorge Flores (EUI) Prof. dr. Regina Grafe (EUI) Prof. dr. Cátia Antunes (Leiden University) Prof. dr. Gert Oostindie, KITLV/Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies © Bram Hoonhout, 2017 No part of this thesis may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without prior permission of the author Researcher declaration to accompany the submission of written work Department of History and Civilization - Doctoral Programme I Bram Hoonhoutcertify that I am the author of the work The West Indian web. Improvising colonial survival in Essequibo and Demerara, 1750-1800 I have presented for examination for the Ph.D. at the European University Institute. I also certify that this is solely my own original work, other than where I have clearly indicated, in this declaration and in the thesis, that it is the work of others. I warrant that I have obtained all the permissions required for using any material from other copyrighted publications. I certify that this work complies with the Code of Ethics in Academic Research issued by the European University Institute (IUE 332/2/10 (CA 297). -

Country Report of Suriname*

UNITED NATIONS E/CONF.103/CRP.1 STATISTICS DIVISION Tenth United Nations Regional Cartographic Conference for the Americas New York, 19-23, August 2013 Item 6(b) of the provisional agenda Country Reports Country report of Suriname* * Prepared by Mr. Hein Raghoebar M.Sc. Introduction Suriname participates since 2009 (formerly in 1986) active in the UNGEGN , SDI , GGIM and UN Spider in Zwitserland . Participations in conferences aims , capacity building and institutional strengthening. This report provides an overview of the status of the Spatial Data Infrastructure of Suriname , status of the Geodesy System of Suriname ( the Global Geospatial Information Management) climate change related disasters in Suriname and the Standardization of the Geographical Names of Suriname for the UNGEGN . 1.Start National Surinamese Spatial Data Infrastructure as a Bridge Between the Society and Modern Digital Technolgy . The proposal is made to Country the Director of the UNDP in Suriname ( march 2013) in what way the project: Start National Spatial Data Infrastructure as a Bridge Between the Surinamese Society and Modern Digital Technolgy can be supported. This project is the result of the Ninth Regional Carthographic Conferences for the America's in New – York 10 – 14 August 2009. At this Conference I was on behalf of the Ministry of Education, the representative of Suriname and a model of the Spatial Data Infrastructure for Suriname was presented . The proposal is done to the UNDP in Suriname to support this project in cooperation with the UN Spatial Data Infrastructure and the General Bureau Of Statistics in Suriname . The design of this institute should ensured the coördination by a national advice council, a council for subsystems and a theme council.