3118 CE 3916 Cover.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hungary's Policy Towards Its Kin Minorities

Hungary’s policy towards its kin minorities: The effects of Hungary’s recent legislative measures on the human rights situation of persons belonging to its kin minorities Óscar Alberto Lema Bouza Supervisor: Prof. Zsolt Körtvélyesi Second Semester University: Eötvös Loránd Tudományegyetem, Budapest, Hungary Academic Year 2012/2013 Óscar A. Lema Bouza Abstract Abstract: This thesis focuses on the recent legislative measures introduced by Hungary aimed at kin minorities in the neighbouring countries. Considering as relevant the ones with the largest Hungarian minorities (i.e. Croatia, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia and Ukraine), the thesis starts by presenting the background to the controversy, looking at the history, demographics and politics of the relevant states. After introducing the human rights standards contained in international and national legal instruments for the protection of minorities, the thesis looks at the reasons behind the enactment of the laws. To do so the politically dominant concept of Hungarian nation is examined. Finally, the author looks at the legal and political restrictions these measures face from the perspective of international law and the reactions of the affected countries, respectively. The research shows the strong dependency between the measures and the political conception of the nation, and points out the lack of amelioration of the human rights situation of ethnic Hungarians in the said countries. The reason given for this is the little effects produced on them by the measures adopted by Hungary and the potentially prejudicial nature of the reaction by the home states. The author advocates for a deeper cooperation between Hungary and the home states. Keywords: citizenship, ethnic preference, Fundamental Law, home state, human rights, Hungary, kin state, minorities, nation, Nationality Law, preferential treatment,Status Law. -

World War I Concept Learning Outline Objectives

AP European History: Period 4.1 Teacher’s Edition World War I Concept Learning Outline Objectives I. Long-term causes of World War I 4.1.I.A INT-9 A. Rival alliances: Triple Alliance vs. Triple Entente SP-6/17/18 1. 1871: The balance of power of Europe was upset by the decisive Prussian victory in the Franco-Prussian War and the creation of the German Empire. a. Bismarck thereafter feared French revenge and negotiated treaties to isolate France. b. Bismarck also feared Russia, especially after the Congress of Berlin in 1878 when Russia blamed Germany for not gaining territory in the Balkans. 2. In 1879, the Dual Alliance emerged: Germany and Austria a. Bismarck sought to thwart Russian expansion. b. The Dual Alliance was based on German support for Austria in its struggle with Russia over expansion in the Balkans. c. This became a major feature of European diplomacy until the end of World War I. 3. Triple Alliance, 1881: Italy joined Germany and Austria Italy sought support for its imperialistic ambitions in the Mediterranean and Africa. 4. Russian-German Reinsurance Treaty, 1887 a. It promised the neutrality of both Germany and Russia if either country went to war with another country. b. Kaiser Wilhelm II refused to renew the reinsurance treaty after removing Bismarck in 1890. This can be seen as a huge diplomatic blunder; Russia wanted to renew it but now had no assurances it was safe from a German invasion. France courted Russia; the two became allies. Germany, now out of necessity, developed closer ties to Austria. -

Routledge Dictionary of Cultural References in Modern French

About the Table of Contents of this eBook. The Table of Contents in this eBook may be off by 1 digit. To correctly navigate chapters, use the bookmark links in the bookmarks panel. The Routledge Dictionary of Cultural References in Modern French The Routledge Dictionary of Cultural References in Modern French reveals the hidden cultural dimension of contemporary French, as used in the press, going beyond the limited and purely lexical approach of traditional bilingual dictionaries. Even foreign learners of French who possess a good level of French often have difficulty in fully understanding French articles, not because of any linguistic shortcomings on their part but because of their inadequate knowledge of the cultural references. This cultural dictionary of French provides the reader with clear and concise expla- nations of the crucial cultural dimension behind the most frequently used words and phrases found in the contemporary French press. This vital background information, gathered here in this innovative and entertaining dictionary, will allow readers to go beyond a superficial understanding of the French press and the French language in general, to see the hidden yet implied cultural significance that is so transparent to the native speaker. Key features: a broad range of cultural references from the historical and literary to the popular and classical, with an in-depth analysis of punning mechanisms. over 3,000 cultural references explained a three-level indicator of frequency over 600 questions to test knowledge before and after reading. The Routledge Dictionary of Cultural References in Modern French is the ideal refer- ence for all undergraduate and postgraduate students of French seeking to enhance their understanding of the French language. -

Plague Mortality in the Seventeenth- Century Low Countries

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/291971008 Was Plague an Exclusively Urban Phenomenon? Plague Mortality in the Seventeenth- Century Low Countries Article in Journal of Interdisciplinary History · August 2016 DOI: 10.1162/JINH_a_00975 CITATIONS READS 0 40 1 author: Daniel Curtis Leiden University 27 PUBLICATIONS 42 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Coordinating for Life. Success and failure of Western European societies in coping with rural hazards and disasters, 1300-1800 View project All content following this page was uploaded by Daniel Curtis on 05 August 2016. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Journal of Interdisciplinary History, XLVII:2 (Autumn, 2016), 139–170. Daniel R. Curtis Was Plague an Exclusively Urban Phenomenon? Plague Mortality in the Seventeenth-Century Low Countries Much current scholarship argues that in early mod- ern northwestern Europe, plagues not only were less severe than the seventeenth-century plagues that ravaged Italy; they were also far less territorially pervasive—remaining mainly in the cities and not spreading easily into the countryside. Such a view connects to a long historiography about early modern plague in northwestern Europe that largely establishes the disease as an urban phenomenon, a nar- rative that is still dominant. This view adds further weight to the “urban graveyards” notion that depicts early modern cities as death traps. From this perspective, extreme rural cases of plague, such as the famous examples of Colyton (Devon) in 1645/6 or Eyam (Derbyshire) in 1665/6 in England, look exceptional, unrepresentative of general epidemiolog- ical trends. -

A TRANSYLVANIAN INTERLUDE on 11 June 1848 Dumitru Brătianu Had

A TRANSYLVANIAN INTERLUDE On 11 June 1848 Dumitru Brătianu had received his accreditation as diplomatic agent in troubled Austria-Hungary, as the first diplomatic representative of modern Romania.221 Until then, Romanian interests abroad had been represented by officials of the Ottoman suzerain power. He travelled via Vienna, where the situation was confused after the collapse of the interim government led by Karl Ludwig von Fic- quelmont, and reached Pest in late June. Since March, under popular pressure, the Habsburg monarchy appeared to have imploded. Vienna as the official centre of power in the Empire was now challenged by Central European “staging-points in the multilateral contestation” during the events of 1848–49:222 Milan, Buda-Pest,223 Prague, Lemberg, Cracow, Timişoara, Braşov, Blaj and Cluj – to mention just a few of the cities engulfed by the protests – were all bursting with revolu- tionary ferment, political and territorial demands and potential multi- ethnic strife. Only one element in the confusing political landscape of 1848–49 remained stable: the now beleaguered Habsburg dynasty and the principle of dynastic loyalty as the pivotal centre of an otherwise explosive multi-national conundrum. After March and especially after the enactment of the April Laws by the Hungarian Diet, the new Hungarian regime had been operat- ing on the basis of a virtual, if brittle, parliamentary sovereignty and autonomy from Austria. A reformist Hungarian government led by Lajos Batthyány comprised the liberal István Széchenyi, the ‘roman- tic hero’ Lajos Kossuth and the ‘man of the future’, Ferenc Deák.224 Embedded within, and extending beyond, the complex network of constitutional, political, economic and military difficulties facing the empire was the thorny nationalities question. -

English/020730-PETAR- 001.Htm 17

HNP DISCUSSION PAPER Public Disclosure Authorized Economics of Tobacco Control Paper No. 18 The Tobacco Epidemic in South-East Europe About this series... Consequences and Policy Responses This series is produced by the Health, Nutrition, and Population Family (HNP) of the World Bank’s Human Development Network. The papers in this series aim to provide a vehicle for publishing preliminary and unpolished results on HNP topics to encourage discussion and Public Disclosure Authorized debate. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the author(s) and should not be attributed in any manner to the World Bank, to its affiliated organizations or to members of its Board of Executive Directors or the countries they represent. Citation and the use of material presented in this series should take into Ivana Bozicevic, Anna Gilmore and Stipe Oreskovic account this provisional character. For free copies of papers in this series please contact the individual authors whose name appears on the paper. Enquiries about the series and submissions should be made directly to the Editor in Chief Alexander S. Preker ([email protected]) or HNP Advisory Service ([email protected], tel 202 473-2256, fax 202 522-3234). For more information, see also www.worldbank.org/hnppublications. The Economics of Tobacco Control sub-series is produced jointly with the Tobacco Free Initiative of the World Health Organization. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the authors and should not be attributed in any Public Disclosure Authorized manner to the World Health Organization or to the World Bank, their affiliated organizations or members of their Executive Boards or the countries they represent. -

Section Iv. Interdisciplinary Studies and Linguistics Удк 821.14

Сетевой научно-практический журнал ТТАУЧНЫЙ 64 СЕРИЯ Вопросы теоретической и прикладной лингвистики РЕЗУЛЬТАТ SECTION IV. INTERDISCIPLINARY STUDIES AND LINGUISTICS УДК 821.14 PENELOPE DELTA, Malapani A. RECENTLY DISCOVERED WRITER Athina Malapani Teacher of Classical & Modern Greek Philology, PhD student, MA in Classics National & Kapodistrian University of Athens 26 Mesogeion, Korydallos, 18 121 Athens, Greece E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] STRACT he aim of this article is to present a Greek writer, Penelope Delta. This writer has re Tcently come up in the field of the studies of the Greek literature and, although there are neither many translations of her works in foreign languages nor many theses or disser tations, she was chosen for the great interest for her works. Her books have been read by many generations, so she is considered a classical writer of Modern Greek Literature. The way she uses the Greek language, the unique characters of her heroes that make any child or adolescent identified with them, the understood organization of her material are only a few of the main characteristics and advantages of her texts. It is also of high importance the fact that her books can be read by adults, as they can provide human values, such as love, hope, enjoyment of life, the educational significance of playing, the innocence of the infancy, the adventurous adolescence, even the unemployment, the value of work and justice. Thus, the educative importance of her texts was the main reason for writing this article. As for the structure of the article, at first, it presents a brief biography of the writer. -

'A Reign of Terror'

‘A Reign of Terror’ CUP Rule in Diyarbekir Province, 1913-1923 Uğur Ü. Üngör University of Amsterdam, Department of History Master’s thesis ‘Holocaust and Genocide Studies’ June 2005 ‘A Reign of Terror’ CUP Rule in Diyarbekir Province, 1913-1923 Uğur Ü. Üngör University of Amsterdam Department of History Master’s thesis ‘Holocaust and Genocide Studies’ Supervisors: Prof. Johannes Houwink ten Cate, Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies Dr. Karel Berkhoff, Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies June 2005 2 Contents Preface 4 Introduction 6 1 ‘Turkey for the Turks’, 1913-1914 10 1.1 Crises in the Ottoman Empire 10 1.2 ‘Nationalization’ of the population 17 1.3 Diyarbekir province before World War I 21 1.4 Social relations between the groups 26 2 Persecution of Christian communities, 1915 33 2.1 Mobilization and war 33 2.2 The ‘reign of terror’ begins 39 2.3 ‘Burn, destroy, kill’ 48 2.4 Center and periphery 63 2.5 Widening and narrowing scopes of persecution 73 3 Deportations of Kurds and settlement of Muslims, 1916-1917 78 3.1 Deportations of Kurds, 1916 81 3.2 Settlement of Muslims, 1917 92 3.3 The aftermath of the war, 1918 95 3.4 The Kemalists take control, 1919-1923 101 4 Conclusion 110 Bibliography 116 Appendix 1: DH.ŞFR 64/39 130 Appendix 2: DH.ŞFR 87/40 132 Appendix 3: DH.ŞFR 86/45 134 Appendix 4: Family tree of Y.A. 136 Maps 138 3 Preface A little less than two decades ago, in my childhood, I became fascinated with violence, whether it was children bullying each other in school, fathers beating up their daughters for sneaking out on a date, or the omnipresent racism that I did not understand at the time. -

Relevant News and Research 7.19 Interventions for Particular Groups

Relevant news and research 7.19 Interventions for particular groups Last updated August 2021 Research: ................................................................................................................................................. 3 7.19.1 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples .................................................................... 7 7.19.2 Smoking cessation among low-income groups ................................................................... 8 7.19.3 Homeless people .................................................................................................................. 16 7.19.4 Smoking cessation for single parents ................................................................................. 19 7.19.5 Serious health conditions .................................................................................................... 19 7.19.5.1 Surgical patients .............................................................................................................. 25 7.19.5.2 Cardiovascular disease .................................................................................................... 28 7.19.5.3 Respiratory diseases ....................................................................................................... 35 7.19.5.4 Cancer ............................................................................................................................. 42 7.19.5.5 Diabetes ......................................................................................................................... -

Mautner, Karl.Toc.Pdf

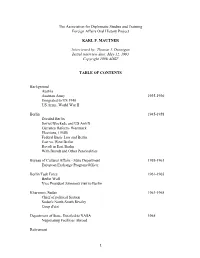

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project KARL F. MAUTNER Interviewed by: Thomas J. Dunnigan Initial interview date: May 12, 1993 opyright 1998 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Austria Austrian Army 1 35-1 36 Emigrated to US 1 40 US Army, World War II Berlin 1 45-1 5, Divided Berlin Soviet Blockade and US Airlift .urrency Reform- Westmark Elections, 01 4,1 Federal Basic 2a3 and Berlin East vs. West Berlin Revolt in East Berlin With Brandt and Other Personalities Bureau of .ultural Affairs - State Department 1 5,-1 61 European E5change Program Officer Berlin Task Force 1 61-1 65 Berlin Wall 6ice President 7ohnson8s visit to Berlin 9hartoum, Sudan 1 63-1 65 .hief of political Section Sudan8s North-South Rivalry .oup d8etat Department of State, Detailed to NASA 1 65 Negotiating Facilities Abroad Retirement 1 General .omments of .areer INTERVIEW %: Karl, my first (uestion to you is, give me your background. I understand that you were born in Austria and that you were engaged in what I would call political work from your early days and that you were active in opposition to the Na,is. ould you tell us something about that- MAUTNER: Well, that is an oversimplification. I 3as born on the 1st of February 1 15 in 6ienna and 3orked there, 3ent to school there, 3as a very poor student, and joined the Austrian army in 1 35 for a year. In 1 36 I got a job as accountant in a printing firm. I certainly couldn8t call myself an active opposition participant after the Anschluss. -

April 2007 � Liebe Leserinnen Und Leser, Neu Auf Der Potsdamer

Die Stadtteilzeitung Ihre Zeitung für Schöneberg - Friedenau - Steglitz Zeitung für bürgerschaftliches Engagement und Stadtteilkultur Ausgabe Nr. 40 - April 2007 www.stadtteilzeitung-schoeneberg.de L Liebe Leserinnen und Leser, Neu auf der Potsdamer Ick sitze inner Küche... Immerhin haben sich doch einige Ring frei für die von Ihnen an den alten Spruch von den Klopsen noch erinnert - Schöneberger! darunter sogar eine Neuberliner (Friedenauer) deutsch-französi- Jetzt geht's Berg auf für Kin- sche Familie! Versprochen ist der, Jugendliche, Erwachsene versprochen, hier ist er: und Senioren aus Schöne- Ick sitze da und esse Klops berg! Schnell Umziehen, Auf- Mit eenmal kloppt's wärmen und dann ab in den Ick kieke, staune, wund're mir Ring 'ne Runde Boxen… Uff eenmal isse uff, die Tür! Nanu, denk ick, ick denk nanu Vor kurzem, am 22. Februar, Jetzt isse uff, erst war se zu? eröffnete in der Potsdamer Ick jehe raus und kieke Straße 152 der Boxclub "Wir und wer steht draußen: icke! aktiv. Boxsport & mehr.". Es ist ein soziales Kiezprojekt und Wen wundert's, dass es diverse gleichzeitig ein neuer Treffpunkt Versionen davon gibt? Wir ha- für sportliche Schöneberger. Auf ben sozusagen eine mittlere ge- ca. 500 Quadratmetern werden wählt, und Elfriede Knöttke unterschiedliche Kurse für Jung freut sich über die Grüße und ist und Alt angeboten. Ehrenamt- ganz glücklich, denn jetzt hat sie Die General-Pape-Straße beginnt (oder endet) am neuen Bahnhof Südkreuz Foto: Thomas Protz lich organisiert und für die ihre Wette gewonnen und ihr Nutzer kostenlos. Es wird sicher Günter muß eine Woche lang L jeder was für seinen "Sportge- abwaschen! Ein Areal mit Überraschungen: v. -

1Daskalov R Tchavdar M Ed En

Entangled Histories of the Balkans Balkan Studies Library Editor-in-Chief Zoran Milutinović, University College London Editorial Board Gordon N. Bardos, Columbia University Alex Drace-Francis, University of Amsterdam Jasna Dragović-Soso, Goldsmiths, University of London Christian Voss, Humboldt University, Berlin Advisory Board Marie-Janine Calic, University of Munich Lenard J. Cohen, Simon Fraser University Radmila Gorup, Columbia University Robert M. Hayden, University of Pittsburgh Robert Hodel, Hamburg University Anna Krasteva, New Bulgarian University Galin Tihanov, Queen Mary, University of London Maria Todorova, University of Illinois Andrew Wachtel, Northwestern University VOLUME 9 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/bsl Entangled Histories of the Balkans Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies Edited by Roumen Daskalov and Tchavdar Marinov LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 Cover Illustration: Top left: Krste Misirkov (1874–1926), philologist and publicist, founder of Macedo- nian national ideology and the Macedonian standard language. Photographer unknown. Top right: Rigas Feraios (1757–1798), Greek political thinker and revolutionary, ideologist of the Greek Enlightenment. Portrait by Andreas Kriezis (1816–1880), Benaki Museum, Athens. Bottom left: Vuk Karadžić (1787–1864), philologist, ethnographer and linguist, reformer of the Serbian language and founder of Serbo-Croatian. 1865, lithography by Josef Kriehuber. Bottom right: Şemseddin Sami Frashëri (1850–1904), Albanian writer and scholar, ideologist of Albanian and of modern Turkish nationalism, with his wife Emine. Photo around 1900, photo- grapher unknown. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Entangled histories of the Balkans / edited by Roumen Daskalov and Tchavdar Marinov. pages cm — (Balkan studies library ; Volume 9) Includes bibliographical references and index.