Copyright by Jennifer Rose Nájera 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Javier Juarez LA FERIA Insurance Advisor 317 S

WEEK OF JANUARY 18, 2012 THROUGH JANUARY 24, 2012 Rudy Garza Funerals, Inc. Packages starting at $2995 with casket Javier Juarez LA FERIA Insurance Advisor 317 S. MAIN Ph. (956) 514-4997 Fax (956) 514-4950 (956) 797-3122 50 N. Vermont, Ste. C 800-425-8202 Mercedes, Tx 78570 Complete Auto Collision Repair Facility Family Owned and Operated by [email protected] 3400 W Expressway 83 PH: 956.797.2525 The Rudy Garza Family La Feria, TX 78559 www.collisionstop.com Auto • Home • Life • Business • Health Free Insurance Estimates Our Family Serving your Family Your Community Newspaper, Serving the Heart of the Rio Grande Valley VOLUME 89 NUMBER 03 LFISD Trustees Recognized for Service Texans benefi t every lessly give of themselves The board members day from the tireless to ensure that decisions serving La Feria Indepen- work and countless hours directly affecting our lo- dent School District are: dedicated by a group of cal schools are made by Mr. Juan Briones, Presi- more than 7,300 men and representatives of this dent, Mr. Alan Moore, women in communities community. In these Vice President, Ms. across the state. These challenging times, they Gloria Casas, Secretary/ public servants are elect- face diffi cult choices and Treasurer, David Bazald- ed to serve by local con- shoulder critical respon- ua, Pancho Cobarrubias, stituents and receive no sibilities. Their ultimate and Javier Loredo. compensation for their goal is always focused Students representing see page 7 efforts. These men and on the future success of each campus will honor women are the school every student enrolled in and recognize Board board members of Texas. -

Baseball Tries for LSC Title Repeat This Weekend the 2015 Lone Star at 6 P.M

Javelina Baseball Goes For LSC Championship Friday & Saturday Nolan Ryan Field VOLUME XV, NO. 39 KINGSVILLE, TEXAS 78363 APRIL 29, 2015 Baseball Tries For LSC Title Repeat This Weekend The 2015 Lone Star at 6 p.m. Friday at Nolan Ryan and entered the contest with a 26- Conference baseball champion will Field and the squads play a 20 record. be determined this weekend and doubleheader beginning at 1 p.m. Clint Andrews, senior third the race between the top three Saturday. baseman from Sugar Land contenders couldn’t be closer. In the earlier series between (Clements), leads the Javelina Defending champion Texas the teams in Stephenville, Tarleton hitting with a .355 average. He A&M-Kingsville and West Texas won three of the four games. has 11 doubles, five triples and a A&M are tied for the lead with 20- The Javelinas had a non- home run. 12 records and Angelo State is conference game with nationally Brayton Carlson, junior one-game back with a 19-13 ranked St. Mary’s Tuesday night (Continued on Page 2) record. The Javelinas will host Tarleton State in a three-game series while West Texas A&M will host Cameron in three games and Angelo State will host Eastern New Mexico in a three-game series. The Javelinas and Texans will meet in a nine-inning single game Lone Star Conference Baseball Standings (Conference Only) Team W L Pct. A&M-Kingsville 20 12 .625 Softball Seniors West Texas A&M 20 12 .625 Three softball players made their final appearances as Javelinas last Angelo State 19 13 .594 weekend. -

1 the Matz Family Has Played an Important Role in Both Harlingen and Cameron County History. the Following Items Document Some

The Matz Family has played an important role in both Harlingen and Cameron County history. The following items document some of its contributions. Presentation About E.O. and Eleanor Matz To Harlingen Historical Preservation Society General Public Meeting Harlingen Public Library November 11, 2005 By James R. Matz 1 I’d like to begin by commending Mary – you and everybody else who is associated with the Harlingen Historical Preservation Society. What you do is something that is so really very important. I had a chance to visit with Rafael for a little bit while we were setting things up. That you are able to attract people like Rafael to become members of your group I think is really great. I also would like to congratulate you folks for what you did at the Harlingen Museum. We became aware of the Dia de los Muertos “the Day of the Dead” exhibits from Mary Lou. The exhibits were outstanding. I just hope that each year more and more people will come and have a chance to see those because it’s obvious that an awful lot time and effort went into what was done. I would like to mention that we have some friends of ours here today, Joan and Rod Olson. They spend four or five months up north where it’s a little bit cooler in the summer and then come down here in the winter time just like the ducks and the geese. So, we’re glad you’re here as well as Lynn Lerberg, their daughter. That having been said, I guess what I’d like to do today is talk a little bit about both Mom and Dad. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Chicana/o Movement and the Catholic Church Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6nk7304p Author Flores, David Jesus Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Chicana/o Movement and the Catholic Church: Católicos por la Raza, PADRES, Las Hermanas A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Chicana and Chicano Studies by David Jesus Flores 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS The Chicana/o Movement and the Catholic Church Católicos por la Raza, PADRES, Las Hermanas by David Jesus Flores Master of Arts in Chicana and Chicano Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor Robert Chao Romero, Chair The role of religion is largely missing from the historical narrative of the Chicana/o power movements of the late 1960’s and early 1970’s. Whereas historians have documented the political, educational, and social changes that resulted from the Chicana/o movement, very few have examined the role of religion. This thesis highlights the intersection of religion and the Chicana/o movement, specifically as it pertained to the Catholic Church. I examine three faith- based organizations founded during the Chicana/o movement and explore their resistance and challenge to the church’s longstanding institutional racism. I argue that the Catholic Church, like other institutions of power challenged during the late 1960’s, experienced its own Chicana/o movement and the field of Chicana/o studies should recognize this important piece of history. -

Many Stars Come from Texas

MANY STARS COME FROM TEXAS. t h e T erry fo un d atio n MESSAGE FROM THE FOUNDER he Terry Foundation is nearing its sixteenth anniversary and what began modestly in 1986 is now the largest Tprivate source of scholarships for University of Texas and Texas A&M University. This April, the universities selected 350 outstanding Texas high school seniors as interview finalists for Terry Scholarships. After the interviews were completed, a record 165 new 2002 Terry Scholars were named. We are indebted to the 57 Scholar Alumni who joined the members of our Board of Directors in serving on eleven interview panels to select the new Scholars. These freshmen Scholars will join their fellow upperclass Scholars next fall in College Station and Austin as part of a total anticipated 550 Scholars: the largest group of Terry Scholars ever enrolled at one time. The spring of 2002 also brought graduation to 71 Terry Scholars, many of whom graduated with honors and are moving on to further their education in graduate studies or Howard L. Terry join the workforce. We also mark 2002 by paying tribute to one of the Foundations most dedicated advocates. Coach Darrell K. Royal retired from the Foundation board after fourteen years of outstanding leadership and service. A friend for many years, Darrell was instrumental in the formation of the Terry Foundation and served on the Board of Directors since its inception. We will miss his seasoned wisdom, his keen wit, and his discerning ability to judge character: all traits that contributed to his success as a coach and recruiter and helped him guide the University of Texas football team to three national championships. -

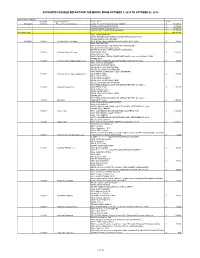

Accounts Payable Report for the Month from October 1, 2018 to October 26, 2018

ACCOUNTS PAYABLE REPORT FOR THE MONTH FROM OCTOBER 1, 2018 TO OCTOBER 26, 2018 Sum of Invoice Amount . Check No Check Payable To Invoice Desc Total 10/1/2018 1133682 Premier Pension Solutions Dental--Premier Pension Solutions--306043 $ 63,537.32 Premier Pension Solutions-306043 $ 4,694.29 Premier Pension Solutions--306043 $ 62,503.89 Vision-Premier Pension Solutions-306043 $ 11,726.02 10/1/2018 Total $ 142,461.52 WHO: DHS BASKETBALL WHAT: OFF-SEASON WORKOUT GEAR WHEN: AUGUST 2018 WHERE: DONNA HIGH SCHOOL 10/3/2018 1133683 All Valley Screen Printing WHY: BASKETBALL WORKOUT GEAR VOUCHER # 15286 $ 625.50 WHO: DHS D'ETTES WHAT: FRIDAY PRACTICE WEAR AND TEAM POLOS WHEN: 2018-2019 SCHOOL YEAR WHERE: DHS WHY: KEEP DANCERS UNIFORMED 1133684 All Valley Screen Printing VOUCHER # 15264 $ 1,323.86 WHO: DHS D'ETTES WHAT: FOOTBALL FRIDAY SPIRIT SHIRT WHEN: 2018-2019 SCHOOL YEAR WHERE: DHS 1133685 All Valley Victory Sports Apparel, Inc WHY: MAKE DANCERS LOOK UNIFORMED VOUCHER # 15284 $ 975.00 WHO: DHS COLORGUARD WHAT: FRIDAY SPIRIT WEAR WHEN: 2018 FOOTBALL SEASON WHERE: DHS AND RGV STADIUMS WHY: MAKE COLORGUARD LOOK UNIFORMED 1133686 All Valley Victory Sports Apparel, Inc VOUCHER # 15308 $ 366.00 WHO: DHS D'ETTES WHAT: DANCE MAKEUP WHEN: 2018-2019 SCHOOL YEAR WHERE: DHS AND RGV STADIUM WHY: MAKE DANCERS LOOK UNIFORMED AND PART OF FEES 1133687 ColorOn Beauty, LLC VOUCHER # 15309 $ 572.00 WHO: DHS D'ETTES WHAT: CAPRI PANTS WHEN: 2018-2019 SCHOOL YEAR WHERE: DHS WHY: MAKE DANCERS LOOK UNIFORMED AND PART OF FEES 1133688 Danzgear VOUCHER # 15327 $ 1,003.20 PACE PURCHASING COOP # P00170 WHO: DHS LIBRARY WHAT: CONCESSION STAND SUPPLIES WHEN: SEPTEMBER 12, 2018 WHERE: DHS LIBRARY 1133689 Sam's Club WHY: CONCESSION STAND SUPPLIES VOUCHER # 15301 $ 1,626.04 PACE PURCHASING COOP # P00170 WHO: DHS LIBRARY WHAT: CONCESSION STAND SUPPLIES WHEN: SEPTEMBER 26, 2018 WHERE: DHS LIBRARY 1133690 Sam's Club WHY: CONCESSION STAND SUPPLIES VOUCHER # 15311 $ 1,636.14 Who: Maria Alicia Gonzalez What: Training When: September, 2018 Where: PRS. -

La Feria I.S.D. Athletic Hand Book 2018-2019

La Feria I.S.D. Athletic Hand Book 2018-2019 1 La Feria I.S.D. Athletic Hand Book 2019-2020 Approved 8/19/19 Table of Contents Sports Available at La Feria High School and William B. Green Jr. High School 3 The Parent’s Role 4 Athletics Communication Form 5 UIL Behavior Expectations of Spectators 6 Guidelines for entering the La Feria Athletic Program 7 Team Selection Criteria 7 Athletic Eligibility 8 Academic Eligibility 8 & 9 Athletic/Academic Conflict Form (see appendix A) 9 Student Absences 9 Student-Athlete Expectations 9 & 10 Participation Eligibility 10 Playing Time 10 Resignation of Sport (see appendix B) 10 Multiple Sport Athletes 10 Transportation (see appendix C) 11 Equipment 11 Locker Room 11 Injuries 11 Athletic Behavior Contract 12 Acknowledgement / Signature Page 16 2 La Feria I.S.D. Athletic Hand Book 2019-2020 Approved 8/19/19 UIL SPORTS OFFERED BY LA FERIA ISD ATHLETICS High School (9-12) Football Volleyball Boys & Girls - Cross Country Boys & Girls - Basketball Boys & Girls - Soccer Boys & Girls - Track Baseball Softball Boys & Girls - Golf Boys & Girls – Tennis Jr. High (7th & 8th) Football Volleyball Boys & Girls - Cross Country Boys & Girls - Basketball Boys & Girls - Track Boys & Girls - Golf Boys & Girls – Tennis Softball Baseball Please note that length of seasons for junior high and high school sports are based on UIL rules. Preparation of practice schedules and times are based on coaching staff, schedule constraints and facility availability. Athletic periods are offered at both the junior high and high school. 3 La Feria I.S.D. Athletic Hand Book 2019-2020 Approved 8/19/19 La Feria ISD Athletics The Parent’s Role As a parent of an interscholastic athlete at La Feria ISD, we want your experience to be exciting, fun, and memorable. -

Poniesbeat the Arena Lighting Ceachlng of a League

* t ..r-- rrrrrr , .r 11, r f r r r r r rr rrr-ffrr-r rrrrrrrf r f.————.. The BROWNSVILLE HERALD SPORTS SECTION msm | rrf rui r, j r r r-fr>Tf rrf rtrrr rrrrr"irr rrrrrrrrrr r rtf s rrrrrrr rtfitrt VALLEY COI Sub-Committee on ! FORMER BROWNSVILLE PLAYER UP WITH GIANTS U. S. Racketeers PLAN TO PUT j Ball League Finds Downing Cubans TO AID A. & M. MIAMI BEACH. Fla.. Feb. 23.—{A*) MIAMI FIGHT ' —Effort.- of Cuban tennis star* to; Favorable stop American players In the anu- Hidalgo Beach-Cuba tournament, a! Miami ■ 4 ■ —, — I ORGANIZATION failed today. One match in the ON OVER AIR O N Boston and Bob Wells, the men s double was halted when dusk further committee appointed by the base- prevented playing. HERALD TO A Cuban star. Miss niseis Com- held Holmes of La Feria ball meeting In Brownsville mallcnga. advanced to finals of the Garden Said last Tuesday mght, by Chairman MEGAPHONE ladies’ singles In the Miami Beach Planning And Reid Are New Guy Trent, to put forth their efforts term! stoumament which also Is To Purchase MIAMI BOUT here. She will meet Mias Giants; to organize Hidalgo county towns under way Eleanor Cottman. of Baltimore, to- Members of to those of Camaron In Battlers Hold Best Aggie join county, The Herald’s "fight party” of morrow. a Valley Class D league, spent at which time Wednesday night, American women made a clean Athletic Staff Thursday and Friday in the upper the will Workouts Yet Stribllng-shsrkev fight of their with the 6-4. -

17Th Annualannual

LA FERIA, TEXAS McHenry700 South TichenorParker Road • LaMuseum Feria, Texas 78559 Project (Private Residence) 17th17th AnnualAnnual 1 Event Program &Visitor’s Guide 2010 3516 East Expressway 83, Suite A Weslaco, Texas 78596 26 1 La Feria,Texas Event Program &Visitor’s Guide 2010 City of La Feria City of La Feria 115 East Commercial Avenue 115 East Commercial Avenue La Feria, Texas 78559 La Feria, Texas 78559 (956) 797-2261 (956) 797-2261 February 2010 February 2010 Greetings, Greetings, Welcome one and all to our 17th annual Fiesta de La Feria. This is when our town The La Feria community just finished one of the best years in its history (2009) despite comes together to celebrate another successful year. Everyone is invited to enjoy great the reeling effects of Hurricane Dolly and the economic meltdown. The visionary food, music, shows, and the unique culture here in south Texas. There are many community building efforts are moving at a fast pace and the positive results can be planned events that range from a Grito contest to a good old-fashioned pie baking seen throughout the community. The compassionate, hardworking residents, dedicated competition. This year’s event gets started at 9:00 AM on Saturday, February 27, 2010. leadership, committed volunteers and employees, and, yes, the blessings from the almighty, are the perfect ingredients for the success we enjoy. Although several La Feria has made some new and welcome changes for its citizens and visitors. I construction and improvement projects have been completed, plans are being pursued extend my invitation for you to try walking the 1 ½ mile walking trail at our new La to undertake more projects, maximizing grant opportunities to benefit the community. -

January January 1 Day of Prayer for Peace Pray for Peace in Our Hearts, Our Homes, Our Communities, Our Country and Our World

January January 1 Day of Prayer for Peace Pray for peace in our hearts, our homes, our communities, our country and our world. Mary of Nazareth: God Bearer. Each of us is asked to bear the peace and love of Christ to the world. January 2 Sadie Alexander (b.1/2/1898 d.11/1/1989) Sadie Alexander was the first black woman to receive a Ph.D. in economics in the United States (1921) and the first woman to earn a law degree from the University of Pennsylvania Law School. She was the first black woman to practice law in Pennsylvania. January 3 Bella Abzug (b.7/24/1920 d.3/31/1998) Bella Abzug was a leading liberal activist and politician, especially known for her advocacy for women’s rights. She graduated from Columbia University’s law school, and became involved the antinuclear peace movement. In the 1960s, she helped organize the Women’s Strike for Peace and the National Women’s Political Caucus. Bella wanted to have a greater impact, so she ran for and won a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives from New York. As a member of congress, she continued to advocate for women’s rights and the withdrawal of troops from Vietnam. Bella Abzug left Congress in 1977, but continued to lend her efforts toward many causes, including the establishment the Women’s Environmental Development Organization. January 4 St. Elizabeth Ann Seaton (b.8/2/1774 d.1/4/1821) Elizabeth Ann Seton, S.C. was the first native-born citizen of the United States canonized by the Roman Catholic Church (September 14, 1975). -

Faculty Handbook

FACULTY HANDBOOK 2020-2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS DISCLAIMER ...................................................................................................... 7 COLLEGE ORGANIZATION ................................................................................. 8 A Brief History of Texas Southmost College ................................................ 8 Mission and Vision of the College .............................................................. 10 Vision Statement ........................................................................................... 10 Mission Statement ......................................................................................... 10 Role and Scope of the College ....................................................................... 10 Values .......................................................................................................... 11 Strategic Goals.............................................................................................. 11 Strategic Priorities ......................................................................................... 11 Board of Trustees ....................................................................................... 12 Accreditation .............................................................................................. 18 State Regulatory Agency ........................................................................... 18 College Administration .............................................................................. 18 -

Accounts Payable Monthly Report from May 25, 2019 To

ACCOUNTS PAYABLE MONTHLY REPORT FROM MAY 25, 2019 TO JUNE 26, 2019 Sum of Invoice Amount Check Dt Check No Check Payable To Invoice Desc Total Who: Child Nutrition Program What: Petty cash When: 2019 summer school Where: Cafeteria Cashier/point of sales Why: to be used for change for a la carte sales for snack 5/28/2019 1141811 GONZALES, PEDRO bar sales $ 150.00 1141811 Total $ 150.00 (WHAT) FULL SHEET CAKE FOR 5TH GRADE STUDENT INCENTIVE (WHO)5TH GRADE TEACHERS - CONCEPCION CHAVEZ, PATRICIA SALAZAR, LYDIA GONZALEZ, ANA LOA, MICHELLE ALCALA (WHERE)ELOY G. SALAZAR ELEMENTARY (WHEN) THURSDAY, MAY 23, 2019 (WHY)INCENTIVE FOR 5TH 1141812 HEB Grocery Company LP GRADE STU $ 37.98 WHAT: 1/2 SHEET CAKE WHEN: MAY 24, 2019 WHERE: OCHOA CAFETERIA WHO: OCHOA KINDER STUDENTS WHY: KINDER GRADUATION CEREMONY $ 37.98 WHAT: EOTY DISTINGUISHED ACHIEVMENT WHO: ZULIA PEDROZA WHEN: MAY 22,2019 WHERE: WA TODD MS WHY: STUDENT RECOGNITION AWARD RECEPTION P0017 $ 103.28 What: Items for Hot Dogs When: May 24, 2019 Where: J.W. Caceres Elem. Who: Pre-K thru 5th Grade Why: EOY field day P.A.C.E. 00170 H.E.B. Crunch Variety Pack Chips 32 ct. $ 258.96 WHAT: REFRESHMENTS FOR BANQUET WHEN: MAY 21, 2019 WHERE: T. PRICE ELEM. SCHOOL WHO: FOR 5TH GRADE STUDENTS WHY: REFRESHMENTS FOR ASSEMBLY FOR 5TH GRADE END OF THE YEAR BANQUET $ 75.96 What: Student Rewards and Supplies When: May 24, 2019 Where: J.W. Caceres Elem. Who: Pre-K thru 5th Grade Students Why: EOY Celebration - Field Day P.A.C.E.