PDF: Westin Motorsports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Porsche Type List

The Porsche Type List When Professor Ferdinand Porsche started his business, the company established a numeric record of projects known as the Type List. As has been reported many times in the past, the list began with Type 7 so that Wanderer-Werke AG did not realize they were the company’s first customer. Of course, as a result, Porsche’s famous car, the 356 as defined on the Type List, was actually Porsche’s 350th design project. In reviewing the Porsche Type List enclosed on this website, you might notice several interesting aspects. First, although there is a strong chronological alignment of Type numbers, it is certainly not perfect. No official explanation exists as to why this occurs. It is possible that Type numbers were originally treated only as an informal configuration and data management tool and today’s rigorous examination of Porsche history is but an aberration of 20/20 hindsight. Secondly, you might also notice that there were variations on Type List numbers that were probably made rather spontaneously. For example, consider the Type 60 with its many “K” variations to designate different body styles. Also consider how the Type 356 was initially a tube frame chassis then changed to a sheet metal chassis with the annotation 356/2 but the /2 later reused to describe different body/engine offerings. Then there were the variants on the 356 annotated as 356 SL, 356A, 356B, and 356C designations and in parallel there were the 356 T1 through 356 T7 designations. Not to mention, of course, the trademark infringement threat that caused the Type 901 to be externally re-designated as the 911. -

Karl E. Ludvigsen Papers, 1905-2011. Archival Collection 26

Karl E. Ludvigsen papers, 1905-2011. Archival Collection 26 Karl E. Ludvigsen papers, 1905-2011. Archival Collection 26 Miles Collier Collections Page 1 of 203 Karl E. Ludvigsen papers, 1905-2011. Archival Collection 26 Title: Karl E. Ludvigsen papers, 1905-2011. Creator: Ludvigsen, Karl E. Call Number: Archival Collection 26 Quantity: 931 cubic feet (514 flat archival boxes, 98 clamshell boxes, 29 filing cabinets, 18 record center cartons, 15 glass plate boxes, 8 oversize boxes). Abstract: The Karl E. Ludvigsen papers 1905-2011 contain his extensive research files, photographs, and prints on a wide variety of automotive topics. The papers reflect the complexity and breadth of Ludvigsen’s work as an author, researcher, and consultant. Approximately 70,000 of his photographic negatives have been digitized and are available on the Revs Digital Library. Thousands of undigitized prints in several series are also available but the copyright of the prints is unclear for many of the images. Ludvigsen’s research files are divided into two series: Subjects and Marques, each focusing on technical aspects, and were clipped or copied from newspapers, trade publications, and manufacturer’s literature, but there are occasional blueprints and photographs. Some of the files include Ludvigsen’s consulting research and the records of his Ludvigsen Library. Scope and Content Note: The Karl E. Ludvigsen papers are organized into eight series. The series largely reflects Ludvigsen’s original filing structure for paper and photographic materials. Series 1. Subject Files [11 filing cabinets and 18 record center cartons] The Subject Files contain documents compiled by Ludvigsen on a wide variety of automotive topics, and are in general alphabetical order. -

A Passion for Porsche a Passion for Porsche

PRSRT STD U.S. Postage PAID FUEL FOR THE MOTORING LIFESTYLE Milwaukee, WI Permit #4523 VOLUME 3: ISSUE 4 | WINTER 2008 a PaSSION for PORSChE LEgENdaRy sports CaRS with a gERMaN aCCENT P.O. Box 87 | Traverse City, MI | 49685 PUBLISHER’S LETTER EDITORIAL STAFF It's hard not to play Executive Publisher MCKEEL HAGERTY favorites when your Associate Publisher JONATHAN A. STEIN first car is a 1967 Managing Editor LORI BREMERKAMP Porsche 911S. Executive Editor JERRY BURTON Copy Editors SHEILA WALSH DETTLOFF, BOB ELLIS Designer MOLLY JEAN Associate Creative Director KRIS BLUMREIch Art Production Manager JOE FERRARO Creative Director LAURA ROGERS Editorial Director DAN GRANTHAM PUBLISHING STAFF Managing Director JEREMY MORRIS Director of Publishing ANGELO ACORD Publication Manager DANIELLE POISSANT Project Manager SCOTT STANISLAV Account Coordinator NIK ARINI Production Manager KATHY COSGRO CONTRIBUTORS CARL BOMSTEAD KEN GROSS ROB SASS JOHN L. STEIN MARCO TRENELLO Questions about the magazine? Call 866-922-9401 or e-mail us Porsche Play at [email protected]. ADVERTISING STAFF I CONFESS TO being a Porsche guy through and through, and not just because my first car was National Sales Manager a 1967 911S. The only two car magazines that came to my house growing up were Road & Track TOM KREMPEL, 586-558-4502 and Porsche Panorama — because we were Porsche Club of America members. [email protected] To me, Porsches have always represented the perfect mix of utilitarian performance and East Coast Sales Office TOM KREMPEL, 586-558-4502 “mostly” understated style. The fact that so much drivability could come from cars with relatively [email protected] little horsepower has always made me think of them as underdogs — even though their racing Central Sales Office history has often proven just the opposite. -

Maxhoffmaninterview.1308361657

Sterling silver 356 occupies a place of honor in Hoffman's Palm Beach home. It was a gift from Ferry Porsche in honor of Hoffman's racing success in 1952. AConversation with MAXHOFFMAN Maximilian E. Hoffman pioneered the marketing biography of Hoffman for Automobile Quarterly. of Porsches in America. He did the same for "About Max Edwin Hoffman there is no shortage of Mercedes-Benz, BMW, Volkswagen, A/fa Romeo, opinions, ofpoints of view. But no one says that he is Lancia, Fiat, Jaguar, and a host of lesser European not interesting. So harsh and intense is the concen makes. From his Frank Lloyd Wright designed trated blue light that Hoffman focuses on his affairs showroom on Park A venue in New York, Hoffman that many cannot stand the glare. Such men are introduced the United States to exotic foreign respected, but not loved, and so it is with Max Hoff automobiles and at the same time persuaded Euro man. " pean manufacturers to design special models and op Hoffman was born near Vienna, Austria, on No tions for the American market. The going was not vember 12, 1904, the son of a wealthy bicycle factory always easy on either side of the Atlantic, but with the owner. From childhood on he was surrounded by patience and persistence of a skilled negotiator and motorcycles and automobiles, racing both with some single-minded determination, Hoffman prevailed. It success as a young man. As he says, he has seen the en is not an exaggeration to suggest that Max Hoffman is tire development of the automobile. -

Registry Template

VolkswagenDas werk American Inspiration When Hitler directed Porsche to develop a people’s car he identified several performance characteristics as well as a cost requirement of less than 1,000 Reichmarks (RM). The latter made for an ambitious undertaking. The profes- sor had only a few months earlier declared in writing that his design for a people’s car could be realistically achieved for a cost around 1,500 RM; 50% more than Hitler allowed. History shows that price was a constant sticking point in developing the Volkswagen. It was not suffi- cient that the car had to be as bare bones as pos- sible. It would also have to be built at a level of efficiency unachievable in Germany at the time. The German car industry was quite aware of the imbalance in automobile cost between Volkswagen AG Corporate History Department) Volkswagen themselves and the world’s leading carmakers. The plant that made the car t is well known to most 356 owners that To put the cost into perspective, a German would their cars incorporated much of the have to work 800 hours to afford the Volkswa- that made the Porsche possible IItechnology originally created for the gen while in the United States, a person only Volkswagen. In fact, it is very likely that the first needed to work 250 hours to buy the cheapest sports car to wear the Porsche name would not Chevrolet. Wages in the United States were ap- have gone into production in Stuttgart without proximately three times those in Germany but support from the entire Volkswagen domain: en- the Reichsverband der Automobilindustrie By Phil Carney gineering, manufacturing, and the Beetle’s sales (RDA) also showed that German car production organization. -

Automobile Quarterly Index

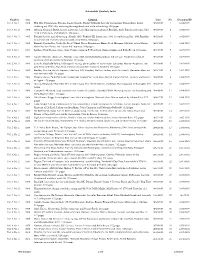

Automobile Quarterly Index Number Year Contents Date No. DocumentID Vol. 1 No. 1 1962 Phil Hill, Pininfarina's Ferraris, Luigi Chinetti, Barney Oldfield, Lincoln Continental, Duesenberg, Leslie 1962:03:01 1 1962.03.01 Saalburg art, 1750 Alfa, motoring thoroughbreds and art in advertising. 108 pages. Vol. 1 No. 2 1962 Sebring, Ormond Beach, luxury motorcars, Lord Montagu's museum at Beaulieu, early French motorcars, New 1962:06:01 2 1962.06.01 York to Paris races and Montaut. 108 pages. Vol. 1 No. 3 1962 Packard history and advertising, Abarth, GM's Firebird III, dream cars, 1963 Corvette Sting Ray, 1904 Franklin 1962:09:01 3 1962.09.01 race, Cord and Harrah's Museum with art portfolio. 108 pages. Vol. 1 No. 4 1962 Renault; Painter Roy Nockolds; Front Wheel Drive; Pininfarina; Henry Ford Museum; Old 999; Aston Martin; 1962:12:01 4 1962.12.01 fiction by Ken Purdy: the "Green Pill" mystery. 108 pages. Vol. 2 No. 1 1963 LeMans, Ford Racing, Stutz, Char-Volant, Clarence P. Hornburg, three-wheelers and Rolls-Royce. 116 pages. 1963:03:01 5 1963.03.01 Vol. 2 No. 2 1963 Stanley Steamer, steam cars, Hershey swap meet, the Duesenberg Special, the GT Car, Walter Gotschke art 1963:06:01 6 1963.06.01 portfolio, duPont and tire technology. 126 pages. Vol. 2 No. 3 1963 Lincoln, Ralph De Palma, Indianapolis racing, photo gallery of Indy racers, Lancaster, Haynes-Apperson, the 1963:09:01 7 1963.09.01 Jack Frost collection, Fiat, Ford, turbine cars and the London to Brighton 120 pages. -

Porsche: Excellence Was Expected

www.porscheroadandrace.com Porsche: Excellence Was Expected Published: 20th November 2019 By: Glen Smale Online version: https://www.porscheroadandrace.com/porsche-excellence-was-expected/ Porsche: Excellence was Expected by Karl Ludvigsen – © Bentley Publishers For many years, Excellence Was Expected, the book on Porsche’s models, motorsport, company history and much more, has been regarded as the final word on the subject. That accolade was well justified because the author, Karl Ludvigsen, has been working in the automotive world all his life, as author and historian, co-author, editor, consultant and as an executive with GM, Fiat and Ford. www.porscheroadandrace.com Karl Ludvigsen examines the latest edition of Porsche: Excellence was Expected – © Bentley Publishers During the sixty years that he has worked in these fields, he has written or co-authored some five dozen books, and needless to say, they are all about cars and the motor industry, Karl’s life-long passion. His writing skills have not just been limited to one marque, or one aspect of motoring, they have included model histories, motorsport, driver biographies, the automotive industry, and photography. Some of the marques he has written on include: Porsche, Mercedes-Benz, Opel, Maserati, Ferrari, Chevrolet Corvette, Ford GT40, Volkswagen, Cunningham, Chaparral and more. Karl Ludvigsen has received many awards for his writing and been recognised by the motor industry for his contribution to research www.porscheroadandrace.com and commentary in Europe and the USA over many decades. In 2002, the Society of Automotive Historians bestowed on him its highest accolade, that of ‘Friend of Automotive History’. [the_ad id=”11938″] www.porscheroadandrace.com Porsche: Excellence was Expected by Karl Ludvigsen – © Bentley Publishers www.porscheroadandrace.com All of this vast automotive experience has placed the author in an ideal position to conduct relevant research, and to build a valuable network of contacts around the world. -

Journalism Awards

automotiveheritageawards 2019 Journalism Awards Our journalism competition honors writers, editors, videographers and others who produce stories focused on automotive history, culture and aesthetics. Entries are from print, web, audio, video, any combination or any other platform. It’s the story-telling we honor. Categories • Best Heritage Car Culture Story • Best Automotive Heritage Travel or Adventure Story • Best Automotive Heritage Personality Profile • Best Heritage Marque-Specific Story • Best Heritage Facility Story – Plant, Museum, Race Track, etc. • Best Heritage Motorsport Story • Best Heritage Restoration or Repair Story • Best Heritage Blog or Column – based on 5 examples • Best Automotive Heritage Book • Best Heritage Audio or Video Story Judging Statement In our second year, with nearly double 2018’s entries, we doubled our number of highly experienced and respected auto journalist/editor judges. And with entries closing on May 31, we had a full month to get our judging completed before results had to be reported by June 30. As before, entries were judged on numerical scales—not vs. each other—for originality of approach, use of language, accuracy/thoroughness, clarity and quality of writing, and the totals of those scores determined awards (if any) earned by each. Again, the quality of entries was high with 16 Gold, 8 Silver, 9 Bronze and 7 “Best in Category” awards earned, the latter for those judged the best Gold Award winners in categories with at least two entries. Sincere gratitude to our distinguished team of judges: Ron Ahrens, John Biel, Paul Brian, Peter Brock, Rich Ceppos, Jill Ciminillo, John Davis, Matt DeLorenzo, Joe DeMatio, Brian Douglas, Lauren Fix, Ken Gross, Charlie Henry, Michael Jordan, John Lamm, Todd Lassa, Preston Lerner, Frank Markus, Mitch McCullough, Jack Nerad, Tony Quiroga, Kim Reynolds, Aaron Robinson, Art St. -

Karl Eric Ludvigsen Erhält Den »Goldenen Kolben 2016«

Pressemitteilung www.f-kubik.de Bremen, im Dezember 2015 Das Forum für Fahrzeuggeschichte F-kubik ehrt auch 2016 eine Persönlichkeit für deren besondere Verdienste um die Fahrzeuggeschichte: Karl Eric Ludvigsen erhält den »Goldenen Kolben 2016« Seit 2006 würdigt jedes Jahr auf der Bremen Classic Motorshow das „Forum für Fahrzeuggeschichte“, kurz F-kubik, eine Persönlichkeit für ihren besonderen Einsatz, authentische Fahrzeuggeschichte in ihrer Vielfalt zu recherchieren, zu dokumentieren und in der Öffentlichkeit zu präsentieren mit dem »Goldenen Kolben«. Die Auszeichnung, eine Urkunde mit einem poliertem Motorkolben, erhält im Februar 2016 der international renommierte Autor Karl Eric Ludvigsen. Mit Ludvigsen ehrt F-kubik eine Persönlichkeit ganz besonderer Reputation. Der »Goldene Kolben« ist jedoch bei weitem nicht die erste Auszeichnung, die dem Amerikaner skandinavischer Abstammung, Jahrgang 1934, zuerkannt wird. Ludvigsen ist in vergangener Zeit in vielen Ländern für seine Werke ausgezeichnet worden – in Deutschland allerdings noch nie. Das wird jetzt nachgeholt. Schließlich ist Ludvigsen auf dem deutschsprachigen Büchermarkt seit 35 Jahren ebenfalls mit einigen erfolgreichen Titeln präsent. Ludvigsen wuchs rund 100 Meilen westlich von Detroit in der Autostadt Kalamazoo, Michigan/ USA, auf, studierte Maschinenbau am Massachusetts Institute of Technology sowie Industriedesign am Pratt Institute. Er erlangte zahlreiche Verdienste um Sicherheit im Automobilwesen, etwa als Gründer der Motor Racing Safety Society. Bei General Motors arbeitete er als Konstrukteur, bevor er zu Fiat Motors of North America ging und dort als Vice President unter anderem verantwortlich war für das Ferrari-Marketing in ganz Nordamerika. Ab 1980 war Ludvigsen – jetzt mit Wohnsitz in England – Vice President bei Ford of Europe, wobei er für Ford die Motorsportaktivitäten in ganz Europa leitete. -

Catalogue 2019/2020

CATALOGUE 2019/2020 Top-quality books by the finest authors CONTACT DETAILS WHAT THE REVIEWERS SAY SALES ENQUIRIES ABOUT EVRO’S BOOKS UK TRADE SALES/DISTRIBUTION Orca Book Services [email protected] +44 (0) 1235 465521 UK AND EUROPE SALES REPRESENTATION Star Book Sales [email protected] +44 (0) 1404 515050 NORTH AMERICAN TRADE SALES/DISTRIBUTION Quarto Publishing Group USA [email protected] John Barnard’s biography, published by Evro in June 2018, reveals a career packed with innovation, including the first carbon-fibre composite +1 860 245 5222 chassis (McLaren) and the first semi-automatic gearbox (Ferrari). EVRO PUBLISHING THE PERFECT CAR THE BIOGRAPHY OF JOHN BARNARD CHAIRMAN ‘John Barnard’s biography is an instant classic, Eric Verdon-Roe and a must-read for anyone with a passion for [email protected] +44 (0) 7831 898332 open-wheel racing... utterly absorbing.’ David Malsher, motorsport.com PUBLISHING DIRECTOR Mark Hughes JIM CLARK [email protected] THE BEST OF THE BEST +44 (0) 7769 642373 ‘The double world champion’s story — personal and sporting — is recounted in great detail and PUBLIC RELATIONS (UK) production standards, as ever with Evro, are from Eventageous PR (Rebecca Leppard) the top drawer… Essential, in a word.’ [email protected] Motor Sport +44 (0) 7749 852481 HOBBO PUBLIC RELATIONS (USA) THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF DAVID HOBBS Judy Stropus [email protected] ‘The problem with most racing driver biographies +1 203 243 2438 is that they often fail to -

Spring 2015 Catalog

Hudson, Wisconsin Spring 2015 Catalog NEW BOOKS! And a new address: we've moved! 2017 O'Neil Rd, Hudson, WI. www.enthusiastbooks.com Enthusiast Books is on the move! After nearly twenty years in a converted roller-rink, we are moving our office/book- store just up the street to 2017 O'Neil Road where we'll continue to showcase a full selection of our own titles, plus the 1000's of used or hard-to-find transportation books of TEWarthAutobooks.biz, and the hundreds of selected titles we stock from other notable transportation publishers. Our store is open Monday through Friday, 9am-3pm. We guarantee hours of browsing enjoyment for the enthusiast! Don't forget to bookmark our website: www.enthusiastbooks.com We have in our warehouse the largest selection of transportation books under one roof anywhere in the world! Enthusiastbooks. com is a division of Iconografix, specialist book publishers since 1992. We publish a number of books each year and have hundreds of transportation-related books from other publishers around the world. We have automotive books, racing books, truck books, books about buses, construction equipment, snowmobiles, ships, farm tractors, trains, motorcycles, RVs, DVDs and more! A little something for everyone, and they make wonderful gifts. In addition, T.E. Warth Esq Automotive Books is located in the same warehouse with out-of-print, hard-to-find, or shopworn books. If you can't find it here, you might find it there. Check out www.tewarthautobooks.biz. Back by popular demand! We are glad to re-introduce many of our previously Back in Print out-of-print titles. -

Published and Distributed RACING and EUROPEAN Car Books

Published and Distributed RACING and EUROPEAN Car Books 2012-2013 Auto Racing NEW Ali/Wings Along for the Ride Autocourse 2011-2012 Motorbooks Workshop Their Design and Application to Racing Cars A Collection of Stories from the Fast The World’s Leading Grand Prix Annual Autocross Performance Enrico Benzing and Furious World of Stock Car Racing Simon Arron Handbook 9.5 x 10.6 in, 280 pages, PB Larry Woody 9 x 12 in, 360 pages, HC Richard Newton 100 + b/w photos 5.5 x 8.25 in, 208 pages, HC 400+ color photos 8.25 x 10.625 in, 160 pages, PB 200187 AE • ISBN: 978-8-87911-539-1 color photos 200435 AE • ISBN: 978-1-90533-461-2 346 color photos $69.95 US/$76.95 CAN 137597 A • ISBN: 978-1-58261-696-4 $59.95 US/$65.00 CAN 144201 AP • ISBN: 978-0-7603-2788-3 $19.95 US $25.95 US/£16.99 UK/$31.95 CAN Barney Hall’s Tales From Ludvigsen Library Series Ludvigsen Library Series The Official Bigoraphy of Trackside BMW Racing Cars Chaparral Cliff Allison Ben White Type 328 to Le Mans V12 Can-Am Racing Cars from Texas From the Fells to Ferrari 5.75 x 8.5 in, 192 pages, HC Karl Ludvigsen Karl Ludvigsen Graham Gauld and Dan Gurney color photos 10.25 x 8.5 in, 128 pages, PB 10.25 x 8.5 in, 128 pages, PB 8.25 x 10 in, 144 pages, HC 144776 AE • ISBN: 978-1-59670-007-9 122 b/w photos color photos 105 color & b/w photos $19.95 US 145950 AE • ISBN: 978-1-58388-201-6 134631 AE • ISBN: 978-1-58388-066-1 146514 AE • ISBN: 978-1-84584-150-8 $29.95 US/$33.95 CAN $39.95 US/$43.99 CAN $22.95 US/$24.99 CAN Colin Chapman Competition Car Competition Car SpeedPro Series Inside