Juan Manuel Fangio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Racing Is Life. Anything Before Or After Is Just Waiting.'

Steve McQueen’s 1963 Ferrari 250 GT Berlinetta Lusso recently went under the hammer at Christie’s in Monterey, offering another reminder of a man whose motoring exploits mirrored some of his most famous onscreen performances. Christopher Kanal pays tribute to a legendary car driven by a screen icon. Thegetaway n 16 August 2007, Steve McQueen’s 1963 Ferrari 250 GT Berlinetta McQueen was also an avid racing enthusiast, performing many of his Lusso went under the hammer at Christies. This remarkable car was own stunts, and at one time considered becoming a professional racing Obought by an anonymous owner, who placed his bid by phone, for driver. Two weeks after breaking an ankle in one bike race, he and co-driver a cool $2.31 million – nearly twice the estimated pre-sale price. The auction Peter Revson raced a Porsche 908/02 in the 12 Hours of Sebring, winning drew 800 people to the Monterey Jet Center in California and attracted their engine class and finishing second to Mario Andretti’s Ferrari by a spirited bidding according to Christie’s Rik Pike. margin of just 23 seconds. So begins another chapter in the life of one of McQueen’s favourite cars, which he drove for nearly a decade. McQueen’s Lusso inspires an almost fetish- like fascination, created from a potent blend of McQueen mythology and an ‘racing IS LIFE. insatiable desire for limited-edition 12-cylinder Ferraris. McQueen is dead 27 years but his iconic status has never been more assured. The Lusso is widely ANYTHING BEFORE acknowledged as Ferrari’s greatest aesthetic and engineering achievement. -

Hitlers GP in England.Pdf

HITLER’S GRAND PRIX IN ENGLAND HITLER’S GRAND PRIX IN ENGLAND Donington 1937 and 1938 Christopher Hilton FOREWORD BY TOM WHEATCROFT Haynes Publishing Contents Introduction and acknowledgements 6 Foreword by Tom Wheatcroft 9 1. From a distance 11 2. Friends - and enemies 30 3. The master’s last win 36 4. Life - and death 72 5. Each dangerous day 90 6. Crisis 121 7. High noon 137 8. The day before yesterday 166 Notes 175 Images 191 Introduction and acknowledgements POLITICS AND SPORT are by definition incompatible, and they're combustible when mixed. The 1930s proved that: the Winter Olympics in Germany in 1936, when the President of the International Olympic Committee threatened to cancel the Games unless the anti-semitic posters were all taken down now, whatever Adolf Hitler decrees; the 1936 Summer Games in Berlin and Hitler's look of utter disgust when Jesse Owens, a negro, won the 100 metres; the World Heavyweight title fight in 1938 between Joe Louis, a negro, and Germany's Max Schmeling which carried racial undertones and overtones. The fight lasted 2 minutes 4 seconds, and in that time Louis knocked Schmeling down four times. They say that some of Schmeling's teeth were found embedded in Louis's glove... Motor racing, a dangerous but genteel activity in the 1920s and early 1930s, was touched by this, too, and touched hard. The combustible mixture produced two Grand Prix races at Donington Park, in 1937 and 1938, which were just as dramatic, just as sinister and just as full of foreboding. This is the full story of those races. -

February 2019 Issue No

February 2019 Issue No. 333 The Journal of The Vintage Sports Car Club of Western Australia (Inc.) Vintage Metal www.vsccwa.com.au 2018 Vintage Stampede Plus: Dad’s Army Christmas Function Doug Todd and the Ballot V8 The Brothers Stanga and the Mille Miglia Book Review: The Singer Story February General Meeting – Monday 4th February 2019 Vintage Sports Car Club of WA (Inc.) ABN 49 845 981 838 Telephone: 0400 813 141 PO Box 1127, GWELUP WA 6018 Email: [email protected] Office Bearers and Officials 2018/19 President: Vacant Treasurer: Graeme Robson mobile: 0407 197 519 Email: [email protected] Secretary: David Moir mobile: 0400 813 141 Email: [email protected] Administrative Officer: Sheryl Swarbrick mob: 0416 025 667 Email: [email protected] Membership/entries correspondence to Sheryl at: PO Box 7277, SPEARWOOD WA 6063 Club Management Committee: Michael Broughton Mobile: 0418 921 544 Email: [email protected] Brian Eyre Mobile: 0409 105 602 Email: [email protected] Ron Fabry Ph: (08) 9457 9179 Email: [email protected] Ed Farrar Mobile: 0409 311 366 Email: [email protected] Mark Jones Ph: (08) 9387 3897 Email: [email protected] Len Kidd Mobile: 0422 797 461 Email: [email protected] Ivan Okey Mobile: 0447 267 938 Email: yekornavi@y ahoo.com.au Competition Secretary: Vacant Dads Army: Ron Fabry Ph: (08) 9457 9179 Email: [email protected] Regalia Officer: Ivan Okey - Mob: 0447 267 938 Email: [email protected] Bar Manager: Graeme Whitehead - 0412 919 370 Membership/Entries Registrar: Sheryl Swarbrick — Email: -

Your Essential Guide to Le Mans 2011

Your essential guide to Le Mans 2011 Go and experience GT racing at the best race track in the world! Nurburgring 24 Hours 23rd - 26th June 2011 • Exclusive trackside camping • From £209.00 per person (based on two people in a car) Including channel crossings, four nights camping, general entrance ticket, including access to the paddock, grid walk and all open grandstands To book or for more information please call us now on 0844 873 0203 www.traveldestinations.co.uk Contents Welcome 02 Before you leave home and driving in France 03 Routes to the circuit from the channel ports 04 Equipment check-list and must-take items 12 On-Circuit camping description and directions 13 Off-Circuit camping and accommodation description and directions 16 The Travel Destinations trackside campsite at Porsche Curves 19 The Travel Destinations Flexotel Village at Antares Sud 22 Friday at Le Mans 25 Circuit and campsites map 26 Grandstands map 28 Points of interest map 29 Bars and restaurants 30 01 Useful local information 31 Where to watch the action 32 2011 race schedule 33 Le Mans 2011 Challengers 34 Teams and car entry list 36 Le Mans 24 Hours previous winners 38 Car comparisons 40 Dailysportscar.com join forces with Travel Destinations 42 Behind the scenes with Radio Le Mans at the 2010 Le Mans 24 Hours 44 On-Circuit assistance helpline 46 Emergency telephone numbers 47 Welcome to the Travel Destinations essential guide to Le Mans 02 24 Hours 2011 Travel Destinations is the UK’s leading tour operator for the Le Mans 24 Hours race and Le Mans Classic. -

Alo-Decals-Availability-And-Prices-2020-06-1.Pdf

https://alodecals.wordpress.com/ Contact and orders: [email protected] Availability and prices, as of June 1st, 2020 Disponibilité et prix, au 1er juin 2020 N.B. Indicated prices do not include shipping and handling (see below for details). All prices are for 1/43 decal sets; contact us for other scales. Our catalogue is normally updated every month. The latest copy can be downloaded at https://alodecals.wordpress.com/catalogue/. N.B. Les prix indiqués n’incluent pas les frais de port (voir ci-dessous pour les détails). Ils sont applicables à des jeux de décalcomanies à l’échelle 1:43 ; nous contacter pour toute autre échelle. Notre catalogue est normalement mis à jour chaque mois. La plus récente copie peut être téléchargée à l’adresse https://alodecals.wordpress.com/catalogue/. Shipping and handling as of July 15, 2019 Frais de port au 15 juillet 2019 1 to 3 sets / 1 à 3 jeux 4,90 € 4 to 9 sets / 4 à 9 jeux 7,90 € 10 to 16 sets / 10 à 16 jeux 12,90 € 17 sets and above / 17 jeux et plus Contact us / Nous consulter AC COBRA Ref. 08364010 1962 Riverside 3 Hours #98 Krause 4.99€ Ref. 06206010 1963 Canadian Grand Prix #50 Miles 5.99€ Ref. 06206020 1963 Canadian Grand Prix #54 Wietzes 5.99€ Ref. 08323010 1963 Nassau Trophy Race #49 Butler 3.99€ Ref. 06150030 1963 Sebring 12 Hours #11 Maggiacomo-Jopp 4.99€ Ref. 06124010 1964 Sebring 12 Hours #16 Noseda-Stevens 5.99€ Ref. 08311010 1965 Nürburgring 1000 Kms #52 Sparrow-McLaren 5.99€ Ref. -

Audi Repeats Last Year's Sebring Victory Quotes After the Race

Sebring, 18 March 2001 Audi repeats last year’s Sebring victory Audi had a successful dress rehersal for the 24 Hour Race at Le Mans: For the second time in a row Team Audi Sport North America took a 1-2 victory at the 12 Hours of Sebring (USA). Michele Alboreto, Laurent Aiello and Rinaldo Capello finished the race just 0.482s ahead of their team mates and last year’s winners Frank Biela, Tom Kristensen and Emanuele Pirro. The Audi customer teams of Champion and Johansson even made it the first 1-2-3-4 victory of Audi in the American Le Mans Series (ALMS) finishing 3rd and 4th. In front of a record crowd of 168,000 spectators, the two Infineon Audi R8s were setting the pace from the start on a track which is famous for being very demanding. The two customer R8s, however, stayed close making the pace among the leaders extremely fast. The two Infineon Audi R8s were fighting for victory for the whole twelve hour distance. Despite the enormous strain, the cars did not suffer from any severe difficulties. The Infineon Audi R8 #1 just had its front brake discs replaced shortly after half distance, the companion car had two pit stops because of a malfunction in the engine’s electrics. For the Audi crew the dress rehersal for Le Mans, however, is not completely over: On Monday and Tuesday the torture of another full 12- hour-distance is on the schedule for one of the two successful Infineon Audi R8s. Quotes after the race Laurent Aiello (#1): “It was a very tough race. -

In Safe Hands How the Fia Is Enlisting Support for Road Safety at the Highest Levels

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF THE FIA: Q1 2016 ISSUE #14 HEAD FIRST RACING TO EXTREMES How racing driver head From icy wastes to baking protection could be deserts, AUTO examines how revolutionised thanks to motor sport conquers all pioneering FIA research P22 climates and conditions P54 THE HARD WAY WINNING WAYS Double FIA World Touring Car Formula One legend Sir Jackie champion José Maria Lopez on Stewart reveals his secrets for his long road to glory and the continued success on and off challenges ahead P36 the race track P66 P32 IN SAFE HANDS HOW THE FIA IS ENLISTING SUPPORT FOR ROAD SAFETY AT THE HIGHEST LEVELS ISSUE #14 THE FIA The Fédération Internationale ALLIED FOR SAFETY de l’Automobile is the governing body of world motor sport and the federation of the world’s One of the keys to bringing the fight leading motoring organisations. Founded in 1904, it brings for road safety to global attention is INTERNATIONAL together 236 national motoring JOURNAL OF THE FIA and sporting organisations from enlisting support at the highest levels. over 135 countries, representing Editorial Board: millions of motorists worldwide. In this regard, I recently had the opportunity In motor sport, it administers JEAN TODT, OLIVIER FISCH the rules and regulations for all to engage with some of the world’s most GERARD SAILLANT, international four-wheel sport, influential decision-makers, making them SAUL BILLINGSLEY including the FIA Formula One Editor-in-chief: LUCA COLAJANNI World Championship and FIA aware of the pressing need to tackle the World Rally Championship. Executive Editor: MARC CUTLER global road safety pandemic. -

Panhard Gilco Colli 1952

Panhard Gilco Colli 1952 Gallerij +32 (0)53 63 12 33 www.marreyt.com [email protected] What a pleasure to be able to present you with another delicious ex- Merk Panhard Mille Miglia sportscar. How else than delicious should I qualify this 1952 Panhard Gilco with Colli "disco volante" aluminium body ? This Model Gilco Colli chassis n° 008145 started life as a barchetta coachbuilt by Allemano. As part of the Ital-France team from Panhard importer Gastone Bouwjaar 1952 Crepaldi, pilot and co-pilot Marchese-Palvarini participated with this barchetta at the 1952 Mille Miglia (startnumber: 2343) and not only won the 750 cc category but also classifying a very honourable 67-th OA. After this succesful Mille Miglia, Crepaldi decided to have chassis 008145 rebodied into a berlinetta aerodynamica by Colli exactly in the same style as the famous "disco volante" Alfa Romeos which were entrusted to Fangio, Kling and Sanesi for the 1953 Mille Miglia. Only 2 Panhards were coachbuilt by Colli in "disco volante" style. In this new configuration, still part of the Ital-France team, chassis number 008145, now registered 207363 MI, was participating at the 1953 Mille Miglia with starting number 2214 now with pilot/co-pilot Girardi-Marcani. After passing Rome, leading once again the 750 category and having covered 3/4 of the race, unfortunately the cranckshaft broke. This berlinetta "disco volante" had nevertheless made a great impression on other participants and onlookers at the side of the road, by demonstrating with panache excellent punch and incredible speed (reaching a top of 175 Km/h) partly thanks to the excellent aerodynamics. -

Bernd Rosemeyer

Sidepodchat – Bernd Rosemeyer Christine: This is show three of five, where Steven Roy turns his written words into an audio extravaganza. These posts were originally published at the beginning of the year on Sidepodcast.com but they are definitely worth a second airing. Steven: Bernd Rosemeyer. Some drivers slide under the door of grand prix racing unnoticed and after serving a respectable apprenticeship get promoted into top drives. Some, like Kimi Räikkönen, fly through the junior formulae so quickly that they can only be granted a license to compete on a probationary basis. One man never drove a race car of any description before he drove a grand prix car and died a legend less than 3 years after his debut with his entire motor racing career lasting less than 1,000 days. Bernd Rosemeyer was born in Lingen, Lower Saxony, Germany on October 14th 1909. His father owned a garage and it was here that his fascination with cars and motor bikes began. The more I learn about Rosemeyer the more he seems like a previous incarnation of Gilles Villeneuve. Like Gilles he had what appeared to be super-natural car control. Like Gilles he seemed to have no fear and like Gilles he didn’t stick rigidly to the law on the road. At the age of 11 he borrowed his father’s car to take some friends for a drive and when at the age of 16 he received his driving license it was quickly removed after the police took a dim view to some of his stunt riding on his motor bike. -

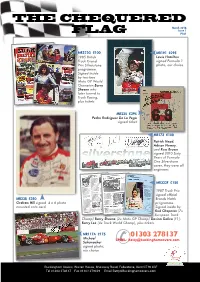

The Chequered Flag

THE CHEQUERED March 2016 Issue 1 FLAG F101 MR322G £100 MR191 £295 1985 British Lewis Hamilton Truck Grand signed Formula 1 Prix Silverstone photo, our choice programme. Signed inside by two-time Moto GP World Champion Barry Sheene who later turned to Truck Racing, plus tickets MR225 £295 Pedro Rodriguez De La Vega signed ticket MR273 £100 Patrick Head, Adrian Newey, and Ross Brawn signed 2010 Sixty Years of Formula One Silverstone cover, they were all engineers MR322F £150 1987 Truck Prix signed official MR238 £350 Brands Hatch Graham Hill signed 4 x 6 photo programme. mounted onto card Signed inside by Rod Chapman (7x European Truck Champ) Barry Sheene (2x Moto GP Champ) Davina Galica (F1), Barry Lee (4x Truck World Champ), plus tickets MR117A £175 01303 278137 Michael EMAIL: [email protected] Schumacher signed photo, our choice Buckingham Covers, Warren House, Shearway Road, Folkestone, Kent CT19 4BF 1 Tel 01303 278137 Fax 01303 279429 Email [email protected] SIGNED SILVERSTONE 2010 - 60 YEARS OF F1 Occassionally going round fairs you would find an odd Silverstone Motor Racing cover with a great signature on, but never more than one or two and always hard to find. They were only ever on sale at the circuit, and were sold to raise funds for things going on in Silverstone Village. Being sold on the circuit gave them access to some very hard to find signatures, as you can see from this initial selection. MR261 £30 MR262 £25 MR77C £45 Father and son drivers Sir Jackie Jody Scheckter, South African Damon Hill, British Racing Driver, and Paul Stewart. -

The Last Road Race

The Last Road Race ‘A very human story - and a good yarn too - that comes to life with interviews with the surviving drivers’ Observer X RICHARD W ILLIAMS Richard Williams is the chief sports writer for the Guardian and the bestselling author of The Death o f Ayrton Senna and Enzo Ferrari: A Life. By Richard Williams The Last Road Race The Death of Ayrton Senna Racers Enzo Ferrari: A Life The View from the High Board THE LAST ROAD RACE THE 1957 PESCARA GRAND PRIX Richard Williams Photographs by Bernard Cahier A PHOENIX PAPERBACK First published in Great Britain in 2004 by Weidenfeld & Nicolson This paperback edition published in 2005 by Phoenix, an imprint of Orion Books Ltd, Orion House, 5 Upper St Martin's Lane, London WC2H 9EA 10 987654321 Copyright © 2004 Richard Williams The right of Richard Williams to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 0 75381 851 5 Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives, pic www.orionbooks.co.uk Contents 1 Arriving 1 2 History 11 3 Moss 24 4 The Road 36 5 Brooks 44 6 Red 58 7 Green 75 8 Salvadori 88 9 Practice 100 10 The Race 107 11 Home 121 12 Then 131 The Entry 137 The Starting Grid 138 The Results 139 Published Sources 140 Acknowledgements 142 Index 143 'I thought it was fantastic. -

Contents Welcome to the World of Racing Orld of Racing

NO. 383 FEBRUARY 2014 Contents Welcome To The World Of Racing Events...................................2 uring this month, I have managed to find a bit of spare time Diary Dates..........................6 Don a Monday evening and after numerous promises to fellow Messages From Margate......7 NSCC member, Chris Gregory I managed to pop along to his local Ninco News........................13 club, Croydon Scalextric Club to give this racing thing a try. Forza Slot.it........................15 Well after my third visit I can say what a great way to spend an Carrera Corner..................19 evening and also a bit of cash! Having been in the winning team at Bits and Pieces....................21 Ramsgate for two years in a row (and no it was a not a fix Mark!) I Chopper’s Woodyard.........23 thought perhaps I could stand shoulder to shoulder in this keen and Swindon Swapmeet...........29 competitive environment.... well actually no I can’t I have so far been Racer Report.....................36 comprehensively beaten virtually every race, coming fourth out of Micro Scalextric History....38 four, although last week I did somehow manage to win a race using Ebay Watch........................41 the club cars? Members Adverts...............44 Peter Simpson, who is also one of the members will be writing Dear NSCC.......................45 a piece soon on the Croydon Club, but in the meantime can I suggest if you have never tried club racing give it a go, if the members are anything like the Croydon mob, it will be a lot of fun and you’ll be made