Note to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mazsalacas Novada Pašvaldības Domes Lēmumu Nr.9.22

APSTIPRINĀTS ar 2020. gada 17. jūnija Mazsalacas novada pašvaldības domes lēmumu Nr.9.22. MAZSALACAS NOVADA PAŠVALDĪBAS 2019. gada publiskais pārskats 1. attēls. Mazsalacas novads no putna lidojuma Mazsalacas novada pašvaldība Pērnavas iela 4, Mazsalaca, Mazsalacas novads, LV-4215 Reģ.Nr. 90009114167; e-pasts: [email protected] Tālr. 25446604; mājas lapa: www.mazsalaca.lv SATURS 1. PAMATINFORMĀCIJA PAR MAZSALACAS NOVADU ......................................... 4 1.1. Mazsalacas novada ģerbonis ............................................................................................ 5 1.2. Mazsalacas novada logo .................................................................................................. 5 1.3. Iedzīvotāji ........................................................................................................................ 5 1.4. Bezdarba līmenis .............................................................................................................. 7 1.5. Ekonomiskais raksturojums ............................................................................................. 8 2. MAZSALACAS NOVADA PAŠVALDĪBAS DARBĪBAS RAKSTUROJUMS ......... 9 2.1. Struktūra ........................................................................................................................... 9 2.2. Pašvaldības iestāžu darbs ............................................................................................... 13 3. MAZSALACAS NOVADA PAŠVALDĪBAS BUDŽETS ......................................... -

ECFG-Latvia-2021R.Pdf

About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success (Photo: A Latvian musician plays a popular folk instrument - the dūdas (bagpipe), photo courtesy of Culture Grams, ProQuest). The guide consists of 2 parts: ECFG Part 1 “Culture General” provides the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment with a focus on the Baltic States. Part 2 “Culture Specific” describes unique cultural features of Latvia Latvian society. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your deployment location. This section is designed to complement other pre-deployment training (Photo: A US jumpmaster inspects a Latvian paratrooper during International Jump Week hosted by Special Operations Command Europe). For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact the AFCLC Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the express permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources. GENERAL CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. -

The Baltic Republics

FINNISH DEFENCE STUDIES THE BALTIC REPUBLICS A Strategic Survey Erkki Nordberg National Defence College Helsinki 1994 Finnish Defence Studies is published under the auspices of the National Defence College, and the contributions reflect the fields of research and teaching of the College. Finnish Defence Studies will occasionally feature documentation on Finnish Security Policy. Views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily imply endorsement by the National Defence College. Editor: Kalevi Ruhala Editorial Assistant: Matti Hongisto Editorial Board: Chairman Prof. Mikko Viitasalo, National Defence College Dr. Pauli Järvenpää, Ministry of Defence Col. Antti Numminen, General Headquarters Dr., Lt.Col. (ret.) Pekka Visuri, Finnish Institute of International Affairs Dr. Matti Vuorio, Scientific Committee for National Defence Published by NATIONAL DEFENCE COLLEGE P.O. Box 266 FIN - 00171 Helsinki FINLAND FINNISH DEFENCE STUDIES 6 THE BALTIC REPUBLICS A Strategic Survey Erkki Nordberg National Defence College Helsinki 1992 ISBN 951-25-0709-9 ISSN 0788-5571 © Copyright 1994: National Defence College All rights reserved Painatuskeskus Oy Pasilan pikapaino Helsinki 1994 Preface Until the end of the First World War, the Baltic region was understood as a geographical area comprising the coastal strip of the Baltic Sea from the Gulf of Danzig to the Gulf of Finland. In the years between the two World Wars the concept became more political in nature: after Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania obtained their independence in 1918 the region gradually became understood as the geographical entity made up of these three republics. Although the Baltic region is geographically fairly homogeneous, each of the newly restored republics possesses unique geographical and strategic features. -

Youth Policies in Latvia

Youth Wiki national description Youth policies in Latvia 2019 The Youth Wiki is Europe's online encyclopaedia in the area of national youth policies. The platform is a comprehensive database of national structures, policies and actions supporting young people. For the updated version of this national description, please visit https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/en/youthwiki 1 Youth 2 Youth policies in Latvia – 2019 Youth Wiki Latvia ................................................................................................................. 7 1. Youth Policy Governance................................................................................................................. 9 1.1 Target population of youth policy ............................................................................................. 9 1.2 National youth law .................................................................................................................... 9 1.3 National youth strategy ........................................................................................................... 11 1.4 Youth policy decision-making .................................................................................................. 12 1.5 Cross-sectoral approach with other ministries ....................................................................... 13 1.6 Evidence-based youth policy ................................................................................................... 14 1.7 Funding youth policy .............................................................................................................. -

Health Systems in Transition

61575 Latvia HiT_2_WEB.pdf 1 03/03/2020 09:55 Vol. 21 No. 4 2019 Vol. Health Systems in Transition Vol. 21 No. 4 2019 Health Systems in Transition: in Transition: Health Systems C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Latvia Latvia Health system review Daiga Behmane Alina Dudele Anita Villerusa Janis Misins The Observatory is a partnership, hosted by WHO/Europe, which includes other international organizations (the European Commission, the World Bank); national and regional governments (Austria, Belgium, Finland, Kristine Klavina Ireland, Norway, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the Veneto Region of Italy); other health system organizations (the French National Union of Health Insurance Funds (UNCAM), the Dzintars Mozgis Health Foundation); and academia (the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) and the Giada Scarpetti London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM)). The Observatory has a secretariat in Brussels and it has hubs in London at LSE and LSHTM) and at the Berlin University of Technology. HiTs are in-depth profiles of health systems and policies, produced using a standardized approach that allows comparison across countries. They provide facts, figures and analysis and highlight reform initiatives in progress. Print ISSN 1817-6119 Web ISSN 1817-6127 61575 Latvia HiT_2_WEB.pdf 2 03/03/2020 09:55 Giada Scarpetti (Editor), and Ewout van Ginneken (Series editor) were responsible for this HiT Editorial Board Series editors Reinhard Busse, Berlin University of Technology, Germany Josep Figueras, European -

All Latvia Cemetery List-Final-By First Name#2

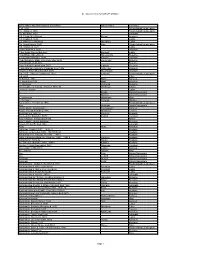

All Latvia Cemetery List by First Name Given Name and Grave Marker Information Family Name Cemetery ? d. 1904 Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava ? b. Itshak d. 1863 Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava ? b. Abraham 1900 Jekabpils ? B. Chaim Meir Potash Potash Kraslava ? B. Eliazar d. 5632 Ludza ? B. Haim Zev Shuvakov Shuvakov Ludza ? b. Itshak Katz d. 1850 Katz Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava ? B. Shalom d. 5634 Ludza ? bar Abraham d. 5662 Varaklani ? Bar David Shmuel Bombart Bombart Ludza ? bar Efraim Shmethovits Shmethovits Rezekne ? Bar Haim Kafman d. 5680 Kafman Varaklani ? bar Menahem Mane Zomerman died 5693 Zomerman Rezekne ? bar Menahem Mendel Rezekne ? bar Yehuda Lapinski died 5677 Lapinski Rezekne ? Bat Abraham Telts wife of Lipman Liver 1906 Telts Liver Kraslava ? bat ben Tzion Shvarbrand d. 5674 Shvarbrand Varaklani ? d. 1875 Pinchus Judelson d. 1923 Judelson Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava ? d. 5608 Pilten ?? Bloch d. 1931 Bloch Karsava ?? Nagli died 5679 Nagli Rezekne ?? Vechman Vechman Rezekne ??? daughter of Yehuda Hirshman 7870-30 Hirshman Saldus ?meret b. Eliazar Ludza A. Broido Dvinsk/Daugavpils A. Blostein Dvinsk/Daugavpils A. Hirschman Hirschman Rīga A. Perlman Perlman Windau Aaron Zev b. Yehiskiel d. 1910 Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava Aba Ostrinsky Dvinsk/Daugavpils Aba b. Moshe Skorobogat? Skorobogat? Karsava Aba b. Yehuda Hirshberg 1916 Hirshberg Tukums Aba Koblentz 1891-30 Koblentz Krustpils Aba Leib bar Ziskind d. 5678 Ziskind Varaklani Aba Yehuda b. Shrago died 1880 Riebini Aba Yehuda Leib bar Abraham Rezekne Abarihel?? bar Eli died 1866 Jekabpils Abay Abay Kraslava Abba bar Jehuda 1925? 1890-22 Krustpils Abba bar Jehuda died 1925 film#1890-23 Krustpils Abba Haim ben Yehuda Leib 1885 1886-1 Krustpils Abba Jehuda bar Mordehaj Hakohen 1899? 1890-9 hacohen Krustpils Abba Ravdin 1889-32 Ravdin Krustpils Abe bar Josef Kaitzner 1960 1883-1 Kaitzner Krustpils Abe bat Feivish Shpungin d. -

Jūrmalas Pilsētas Domes Tūrismu Veicinoši Pasākumi Tūrisma Statistika Sadalījums Pa Valstīm Baltijas Valstu Tūristu Skaita Salīdzinājums 2012.–2015

Jūrmalas pilsētas domes tūrismu veicinoši pasākumi Tūrisma statistika Sadalījums pa valstīm Baltijas valstu tūristu skaita salīdzinājums 2012.–2015. gads NVS valstu tūristu skaita salīdzinājums 2012.–2015. gads Skandināvijas valstu un Vācijas tūristu skaita salīdzinājums 2012.–2015. gads Igaunija •Izstāde Tourest TAVA stendā/ 13.-15. februāris •Brošūra «Jūrmala 2015» igauņu valodā •Reklāmas lapa A4 Postimees laikrakstā/ 14. marts •Reklāmraksts Postimees pielikumā «Aktīvā atpūta Latvijā»/ maijs •Igaunijas glancēto sieviešu un vīriešu žurnālu pārstāvju uzņemšana/ maijs •Igaunijas TV uzņemšana Jūrmalā/ 12.-16. jūnijs •Reklāmas lapa A4 Postimees laikrakstā/ rudens •Newspaper Postimees (Igaunijā) •Žurnāls HELLO (Igaunijā) •Žurnāls ARTER (Igaunijā) •Supplement Puhkus Latis (Igaunijā) Newspaper Postimees Külastage meid Tallinn Tartu Pärnu Riga Vilnius Meil on hea meel tervitada iga külalist ja me kutsume kõiki avastama Jūrmalat kogu selle mitmekesisuses: tutvuma ajaloo, rikka kultuurielu ja eri puhkevõimalustega; nautima merd, tuult, Tere tulemast päikest ja loodust. Jūrmala on kohtumispaik, koht, kust leida inspiratsiooni ja kuhu on ikka ja jälle hea tagasi tulla. Tere tulemast meie Jūrmalasse! külalislahkesse linna! Vaatetorn ja pere kurada, Putukarada, Männirada ja Taime- Rand rabarada. Pärast suuri rekonstrueerimis- rada. Radade juurde on rajatud avarad töid avati taas Kemeri raba laudtee, millel puhkepark Dzintari’s www.tourism.jurmala.lv vaateplatvormid, turvalised ja mugavad saab nüüd teha imelise jalutuskäigu puu- Rand on varustatud riietuskabiinide -

Circular Economy and Bioeconomy Interaction Development As Future for Rural Regions. Case Study of Aizkraukle Region in Latvia

Environmental and Climate Technologies 2019, vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 129–146 doi: 10.2478/rtuect-2019-0084 https://content.sciendo.com Circular Economy and Bioeconomy Interaction Development as Future for Rural Regions. Case Study of Aizkraukle Region in Latvia Indra MUIZNIECE1*, Lauma ZIHARE2, Jelena PUBULE3, Dagnija BLUMBERGA4 1–4Institute of Energy Systems and Environment, Riga Technical University, Azenes iela 12/1, Riga, LV-1048, Latvia Abstract – In order to enforce the concepts of bioeconomy and the circular economy, the use of a bottom-up approach at the national level has been proposed: to start at the level of a small region, encourage its development, considering its specific capacities and resources, rather than applying generalized assumptions at a national or international level. Therefore, this study has been carried out with an aim to develop a methodology for the assessment of small rural areas in the context of the circular economy and bioeconomy, in order to advance the development of these regions in an effective way, using the existing bioresources comprehensively. The methodology is based on the identification of existing and potential bioeconomy flows (land and its use, bioresources, human resources, employment and business), the identification of the strengths of their interaction and compare these with the situation at the regional and national levels in order to identify the specific region's current situation in the bioeconomy and identify more forward-looking directions for development. Several methods are integrated and interlinked in the methodology – indicator analysis, correlation and regression analysis, and heat map tables. The methodology is approbated on one case study – Aizkraukle region – a small rural region in Latvia. -

From Tribe to Nation a Brief History of Latvia

From Tribe to Nation A Brief History of Latvia 1 Cover photo: Popular People of Latvia are very proud of their history. It demonstration on is a history of the birth and development of the Dome Square, 1989 idea of an independent nation, and a consequent struggle to attain it, maintain it, and renew it. Above: A Zeppelin above Rīga in 1930 Albeit important, Latvian history is not entirely unique. The changes which swept through the ter- Below: Participants ritory of Latvia over the last two dozen centuries of the XXV Nationwide were tied to the ever changing map of Europe, Song and Dance and the shifting balance of power. From the Viking Celebration in 2013 conquests and German Crusades, to the recent World Wars, the territory of Latvia, strategically lo- cated on the Baltic Sea between the Scandinavian region and Russia, was very much part of these events, and shared their impact especially closely with its Baltic neighbours. What is unique and also attests to the importance of history in Latvia today, is how the growth and development of a nation, initially as a mere idea, permeated all these events through the centuries up to Latvian independence in 1918. In this brief history of Latvia you can read how Latvia grew from tribe to nation, how its history intertwined with changes throughout Europe, and how through them, or perhaps despite them, Lat- via came to be a country with such a proud and distinct national identity 2 1 3 Incredible Historical Landmarks Left: People of The Baltic Way – this was one of the most crea- Latvia united in the tive non-violent protest activities in history. -

Cartella Stampa 2017

CARTELLA STAMPA 2017 INDICE INTRODUZIONE 4 CATALOGNA, DESTINAZIONE DI QUALITÀ 8 ATTRAZIONI TURISTICHE 11 ALLOGGI TURISTICI 14 MARCHI TURISTICI 17 Costa Brava 18 Costa Barcelona 20 Barcelona 22 Costa Daurada 24 Terres de l’Ebre 26 Pirineus 28 Terres de Lleida 30 Val d’Aran 32 Paisatges Barcelona 34 ESPERIENZE TURISTICHE 36 Attività in spazi naturali e rurali 38 Catalogna accessibile 41 Sport 44 Enoturismo 46 Gastronomia 48 Grandi icone e grandi itinerari 50 Trekking e cicloturismo 52 Turismo medico e di salute 54 Premium 55 Turismo d'affari 56 Vacanze in famiglia 58 NOVITÀ 2017 60 INDIRIZZI UTILI 74 INTRODUZIONE La Catalogna è un paese mediterraneo, con una storia millenaria, una cultura e una lingua proprie ed un rilevante patrimonio monumentale e paesaggistico. Abitanti. 7,5 milioni Superficie. 32.107 km2 Territorio. La geografia catalana presenta paesaggi molto vari: - I 580 chilometri di costa mediterranea includono la Costa Brava, Costa Barcelo- na, Barcelona, la Costa Daurada e Terres de l’Ebre. - I Pirenei catalani, con vette che arrivano fino ai 3.000 metri, caratterizzano la zona settentrionale del Paese. Spicca in particolar modo la Val d’Aran, una valle orientata verso l’Atlantico che ha conservato una cultura, una lingua – l’aranese – e istituzioni di governo proprie. - Tanto la capitale catalana, Barcellona, come i tre capoluoghi provinciali, Girona, Tarragona e Lleida vantano molteplici attrazioni. Nel resto della Catalogna, tro- viamo numerosi centri di spiccato carattere e dotati di un notevole patrimonio: città antiche ristrutturate, edifici che spaziano dal romanico al modernismo ed un ampio ventaglio di musei invitano a visitarle. -

Sightseeing in Aizpute

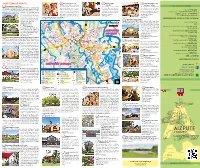

SIGHTSEEING IN AIZPUTE 9 Valda Jēriņa Dolls room 14 Weavers’ Studio 20 Centre of workshops and The exposition shows a collection “Kamolītis” residences “SERDE” WWW.VISITAIZPUTE.LV 1 Livonian Order Castle Ruins of dolls created by national theatre The workshop offers its visitors This set of historical buildings, with th The Livonian Order built the fortifications in the 13 century. In the actress Valda Jēriņa. There are more to see the process of different its creative ambience, welcomes – 113, 112 113, – Ambulance th 15 century, a residential house was built at its eastern wall, with than 500 thematically dressed dolls canvas being woven in the looms you to enjoy a variety of cultural – (+371) 26475143 (+371) – police municipal county Aizpute cellars and a gallery; thus the fortifications were turned into a castle. in the collection: dolls in national according to ancient methods tourism opportunities, art and – 110, 112, (+371) 63448192 (+371) 112, 110, – It served as a border fortification at police State costumes, school uniforms, theatrical and using traditional ornaments. cultural events (open in summer). the cross point of the territories of – 112 – and fantasy costumes. There is a Katoļu iela 1, Aizpute, Atmodas iela 9, Aizpute, departament Rescue and Fire the Livonian Order and the Bishop children’s playroom next to the (+371) 22847115 (+371) 29817180, of Courland (Latvian: Kurzeme). exhibition halls. Book your visit in advance. www.serde.lv EMERGENCY OF CASES IN CALL TO WHERE The river Tebra was the border: the Katoļu iela 1, Aizpute, (+371) 28617307 Bishopric on the right bank and the 21 “IDEJU MĀJA” (IDEA HOUSE) (+371) 25125190 (+371) Phone: Livonian Order on the left. -

The Saeima (Parliament) Election

/pub/public/30067.html Legislation / The Saeima Election Law Unofficial translation Modified by amendments adopted till 14 July 2014 As in force on 19 July 2014 The Saeima has adopted and the President of State has proclaimed the following law: The Saeima Election Law Chapter I GENERAL PROVISIONS 1. Citizens of Latvia who have reached the age of 18 by election day have the right to vote. (As amended by the 6 February 2014 Law) 2.(Deleted by the 6 February 2014 Law). 3. A person has the right to vote in any constituency. 4. Any citizen of Latvia who has reached the age of 21 before election day may be elected to the Saeima unless one or more of the restrictions specified in Article 5 of this Law apply. 5. Persons are not to be included in the lists of candidates and are not eligible to be elected to the Saeima if they: 1) have been placed under statutory trusteeship by the court; 2) are serving a court sentence in a penitentiary; 3) have been convicted of an intentionally committed criminal offence except in cases when persons have been rehabilitated or their conviction has been expunged or vacated; 4) have committed a criminal offence set forth in the Criminal Law in a state of mental incapacity or a state of diminished mental capacity or who, after committing a criminal offence, have developed a mental disorder and thus are incapable of taking or controlling a conscious action and as a result have been subjected to compulsory medical measures, or whose cases have been dismissed without applying such compulsory medical measures; 5) belong