The Making of Meo Marginality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SYNOPSIS of DEBATE ______(Proceedings Other Than Questions and Answers) ______Friday, March 19, 2021 / Phalguna 28, 1942 (Saka) ______OBSERVATION by the CHAIR 1

RAJYA SABHA _______ SYNOPSIS OF DEBATE _______ (Proceedings other than Questions and Answers) _______ Friday, March 19, 2021 / Phalguna 28, 1942 (Saka) _______ OBSERVATION BY THE CHAIR 1. MR. CHAIRMAN: Hon. Members, I have an appeal to make in view of the reports coming from certain States that the virus pandemic is spreading. So, I only appeal to all the Members of Parliament who are here, who are there in their respective fields to be extra careful. I know that you are all public representatives, You can't live in isolation. At the same time while dealing with people, meeting them or going to your constituency or other areas, be careful. Strictly follow the advice given by the Healthy Ministry, Home Ministry, Central Government as well as the guidelines issued by the State Governments concerned from time to time and see to it that they are followed. My appeal is not only to you, but also to the people in general. The Members of Parliament should take interest to see that the people are guided properly. We are seeing that though the severity has come down, but the cases are spreading here and there. It is because the people in their respective areas are not following discipline. This is a very, very important aspect. We should not allow the situation to deteriorate. We are all happy, the world is happy, the country is happy, people are happy. We have been able to contain it, and we were hoping that we would totally succeed. Meanwhile, these ___________________________________________________ This Synopsis is not an authoritative record of the proceedings of the Rajya Sabha. -

BAYANA the First Lavishly Illustrated and Comprehensive Record of the Historic Bayana Region

BAYANA The first lavishly illustrated and comprehensive record of the historic Bayana region Bayana in Rajasthan, and its monuments, challenge the perceived but established view of the development of Muslim architecture and urban form in India. At the end of the 12th century, early conquerors took the mighty Hindu fort, building the first Muslim city below on virgin ground. They later reconfigured the fort and constructed another town within it. These two towns were the centre of an autonomous region during the 15th and 16th centuries. Going beyond a simple study of the historic, architectural and archaeological remains, this book takes on the wider issues of how far the artistic traditions of Bayana, which developed independently from those of Delhi, later influenced north Indian architecture. It shows how these traditions were the forerunners of the Mughal architectural style, which drew many of its features from innovations developed first in Bayana. Key Features • The first comprehensive account of this historic region • Offers a broad reinvestigation of North Indian Muslim architecture through a case study of a desert fortress MEHRDAD SHOKOOHY • Includes detailed maps of the sites: Bayana Town, the Garden City of NATALIE H. SHOKOOHY Sikandra and the Vijayamandargarh or Tahangar Fort with detailed survey of its fortifications and its elaborate gate systems • Features photographs and measured surveys of 140 monuments and epigraphic records from the 13th to the end of the 16th century – including mosques, minarets, waterworks, domestic dwellings, mansions, ‘īdgāhs (prayer walls) and funerary edifices • Introduces historic outlying towns and their monuments in the region such as Barambad, Dholpur, Khanwa and Nagar-Sikri (later to become Fathpur Sikri) • Demonstrates Bayana’s cultural and historic importance in spite of its present obscurity and neglect BAYANA • Adds to the record of India’s disappearing historic heritage in the wake of modernisation. -

Exhibitions Director Archives Dept

Phone:2561412 rdi I I r 431, SECTOR 2. PANCHKULA-134 112 ; j K.L.Zakir HUA/2006-07/ Secretary Dafeci:")/.^ Subject:-1 Seminar on the "Role of Mewat in the Freedom Struggle'i. Dearlpo ! I The Haryana Urdu Akademi, in collaboration with the District Administration Mewat, proposes to organize a Seminar on the "Role of Mewat in the Freedom Struggle" in the 1st or 2^^ week of November,2006 at Nuh. It is a very important Seminar and everyone has appreciated this proposal. A special meeting was organized a couple of weeks back ,at Nuh. A list ojf the experts/Scholars/persons associated with the families of the freedom fighters was tentatively prepared in that meeting, who could be aiv requ 3Sted to present their papers in the Seminar. Your name is also in this list. therefore, request you to please intimate the title of the paper which you ^ould like to present in the Seminar. The Seminar is expected to be inaugurated by His Excellency the Governor of Haryana on the first day of the Seminar. On the Second day, papers will be presented by the scholars/experts/others and in tlie valedictory session, on the second day, a report of the Seminar will be presented along with the recommendations. I request you to see the possibility of putting up an exhibition during the Seminar at Nuh, in the Y.M.D. College, which would also be inaugurated by His Excellency on the first day and it would remain open for the students of the college ,other educational intuitions and general public, on the second day. -

Chronicles of Rajputana: the Valour, Sacrifices and Uprightness of Rajputs

Quest Journals Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Science Volume 9 ~ Issue 8 (2021)pp: 15-39 ISSN(Online):2321-9467 www.questjournals.org Research Paper Chronicles of Rajputana: the Valour, Sacrifices and uprightness of Rajputs Suman Lakhani ABSTRACT Many famous kings and emperors have ruled over Rajasthan. Rajasthan has seen the grandeur of the Rajputs, the gallantry of the Mughals, and the extravagance of Jat monarchs. None the less history of Rajasthan has been shaped and molded to fit one typical school of thought but it holds deep secrets and amazing stories of splendors of the past wrapped in various shades of mysteries stories. This paper is an attempt to try and unearth the mysteries of the land of princes. KEYWORDS: Rajput, Sesodias,Rajputana, Clans, Rana, Arabs, Akbar, Maratha Received 18 July, 2021; Revised: 01 August, 2021; Accepted 03 August, 2021 © The author(s) 2021. Published with open access at www.questjournals.org Chronicles of Rajputana: The Valour, Sacrifices and uprightness of Rajputs We are at a fork in the road in India that we have traveled for the past 150 years; and if we are to make true divination of the goal, whether on the right hand or the left, where our searching arrows are winged, nothing could be more useful to us than a close study of the character and history of those who have held supreme power over the country before us, - the waifs.(Sarkar: 1960) Only the Rajputs are discussed in this paper, which is based on Miss Gabrielle Festing's "From the Land of the Princes" and Colonel James Tod's "Annals of Rajasthan." Miss Festing's book does for Rajasthan's impassioned national traditions and dynastic records what Charles Kingsley and the Rev. -

Module 1A: Uttar Pradesh History

Module 1a: Uttar Pradesh History Uttar Pradesh State Information India.. The Gangetic Plain occupies three quarters of the state. The entire Capital : Lucknow state, except for the northern region, has a tropical monsoon climate. In the Districts :70 plains, January temperatures range from 12.5°C-17.5°C and May records Languages: Hindi, Urdu, English 27.5°-32.5°C, with a maximum of 45°C. Rainfall varies from 1,000-2,000 mm in Introduction to Uttar Pradesh the east to 600-1,000 mm in the west. Uttar Pradesh has multicultural, multiracial, fabulous wealth of nature- Brief History of Uttar Pradesh hills, valleys, rivers, forests, and vast plains. Viewed as the largest tourist The epics of Hinduism, the Ramayana destination in India, Uttar Pradesh and the Mahabharata, were written in boasts of 35 million domestic tourists. Uttar Pradesh. Uttar Pradesh also had More than half of the foreign tourists, the glory of being home to Lord Buddha. who visit India every year, make it a It has now been established that point to visit this state of Taj and Ganga. Gautama Buddha spent most of his life Agra itself receives around one million in eastern Uttar Pradesh, wandering foreign tourists a year coupled with from place to place preaching his around twenty million domestic tourists. sermons. The empire of Chandra Gupta Uttar Pradesh is studded with places of Maurya extended nearly over the whole tourist attractions across a wide of Uttar Pradesh. Edicts of this period spectrum of interest to people of diverse have been found at Allahabad and interests. -

Gender and Migration: Negotiating Rights a Women's Movement

CENTRE FOR WOMEN’S DEVELOPMENT STUDIES NEW DELHI Final Technical Report of the Project on Gender and Migration: Negotiating Rights A Women’s Movement Perspective IDRC Grant No. 103978-001 Research Institution: Centre for Women's Development Studies 25 Bhai Vir Singh Marg, New Delhi, India Project Area: India Date January 2012 Supported by: 1 CENTRAL RESEARCH TEAM Project Director Dr. Indu Agnihotri Asst. Project Director Ms. Indrani Mazumdar Dr. Neetha N. Research Associates Ms. Taneesha Devi Mohan Ms. Shruti Chaudhry Administrative Assistance Mr. Nandan Pillai 2 CONTENTS 1 ABSTRACT & KEY WORDS 2 FINAL TECHNICAL REPORT 3 BACKGROUND AND CONCEPT NOTES FOR REGIONAL CONSULTATIONS 4 REGIONAL CONSULTATION REPORTS 5 QUESTIONNAIRES & CODE SHEETS 6 RESEARCH TEAM PAPERS & NOTES 3 ABSTRACT The new knowledge on the experience of women and internal migration in India that has been generated by this research project covers a vast terrain. A consultation process across seven regions has generated a rich resource of papers/presentations that map the gendered migration patterns in different parts of India. The project has devised a new method for assessing women’s work/employment situation in the country through separation of paid and unpaid work in the official macro-data, which has in turn allowed for a construction of a picture of female labour migration, that was hitherto camouflaged by the dominance of marriage migration in the official data. A meso-level survey covering more than 5000 migrants and their households across 20 states in India has demonstrated that migration has led to the concentration of women in a relatively narrow range of occupations/industries. -

7 Battles of Mughal Army

Battles of Mughal Army Module - II Military History of Medieval India 7 BATTLES OF MUGHAL ARMY Note In the previous lesson, you studied the factors that encouraged Babur to invade India, composition of the Mughal Army and their war equipment and weapons. You also learnt that the Mughal artillery was a new weapon of war and terrifying to the enemies. The gunpowder played a vital role in winning battles and in the establishment and expansion of the Mughal empire. In this lesson, you will study the three important battles fought by Babur which laid a solid foundation of the Mughal rule in India. Panipat (a town in Haryana) has been described as the pivot of Indian history for 300 years. And its story begins in the first great battle that took place in 1526. The victory at Panipat, significant as it was, did not allow Babur the luxury to sit back and savour the moment for long. For there were other enemies such as that of Rana Sanga, the powerful ruler of Mewar to be subdued in land called Hindustan. After capturing Delhi, Babur lived for only four more years. His son Humayun and grandson Akbar continued the consolidation of Mughal power after his death. Although Mughal influence reached its political peak during Akbar's time, the foundation was laid by Akbar's grandfather. Objectives After studing this lesson you will be able to: explain the first battle of Panipat and battle field tactics of the Mughals and discuss the power-struggle that existed during the early years of the Mughal Dynasty. -

Bareilly Zone CSC List

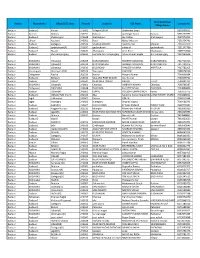

S Grampanchayat N District Block Name Village/CSC name Pincode Location VLE Name Contact No Village Name o Badaun Budaun2 Kisrua 243601 Village KISRUA Shailendra Singh 5835005612 Badaun Gunnor Babrala 243751 Babrala Ajit Singh Yadav Babrala 5836237097 Badaun Budaun1 shahavajpur 243638 shahavajpur Jay Kishan shahavajpur 7037970292 Badaun Ujhani Nausera 243601 Rural Mukul Maurya 7351054741 Badaun Budaun Dataganj 243631 VILLEGE MARORI Ajeet Kumar Marauri 7351070370 Badaun Budaun2 qadarchowk(R) 243637 qadarchowk sifate ali qadarchowk 7351147786 Badaun Budaun1 Bisauli 243632 dhanupura Amir Khan Dhanupura 7409212060 Badaun Budaun shri narayanganj 243639 mohalla shri narayanganj Ashok Kumar Gupta shri narayanganj 7417290516 Badaun BUDAUN1 Ujhani(U) 243639 NARAYANGANJ SHOBHIT AGRAWAL NARAYANGANJ 7417721016 Badaun BUDAUN1 Ujhani(U) 243639 NARAYANGANJ SHOBHIT AGRAWAL NARAYANGANJ 7417721016 Badaun BUDAUN1 Ujhani(U) 243639 BILSI ROAD PRADEEP MISHRA AHIRTOLA 7417782205 Badaun Vazeerganj Wazirganj (NP) 202526 Wazirganj YASH PAL 7499478130 Badaun Dahgawan Nadha 202523 Nadha Mayank Kumar 7500006864 Badaun Budaun2 Bichpuri 243631 VILL AND POST MIAUN Atul Kumar 7500379752 Badaun Budaun Ushait 243641 NEAR IDEA TOWER DHRUV Ushait 7500401211 Badaun BUDAUN1 Ujhani(R) 243601 Chandau AMBRISH KUMAR Chandau 7500766387 Badaun Dahgawan DANDARA 243638 DANDARA KULDEEP SINGH DANDARA 7534890000 Badaun Budaun Ujhani(R) 243601 KURAU YOGESH KUMAR SINGH Kurau 7535079775 Badaun Budaun2 Udhaiti Patti Sharki 202524 Bilsi Sandeep Kumar ShankhdharUGHAITI PATTI SHARKI 7535868001 -

The Architecture of Fatehpur Sikri

THE ARCHITECTURE OF FATEHPUR SIKRI Dissertation Submitted for the Degree of M. Phil. BY SHIVANI SINGH Under the Supervision of DR. J. V. SINGH AGRE CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) MAY, 1995 DS2558 ,i.k *i' ••J-jfM/fjp ^6"68 V :^;j^^»^ 1 6 FEB W(> ;»^ j IvJ /\ S.'D c;v^•c r/vu ' x/ ^-* 3 f«d In Coflnp«< CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY TELEPHONE : 5546 DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH, U.P. M«r 31, 1995 Thl« Is to certify that tiM M.Phil 4iM«rt«tion •Btitlad* *Arca>lt<ictar« of FstrtaHir aikri* miikm±ttmd by Mrs. Shlvonl ftlagti 1» Iwr odgi&al woxk and is soitsbls for sulMiiisslon. T (J«g^ Vlr Slagh Agrs) >8h«x«s* • ****•**********."C*** ******* TO MY PARENTS ** **lr*******T*************** ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I wish to express my profound gratitude to my supervisor Dr. J.V, Singh Agre for his unstinted guid ance, valuable suggestions and critical analysis of the present study. I am also grateful to- a) The Chairman, Department of Histoiry, A,i-i.u., Aligarh, b) The ICHR for providing me financial assistance and c) Staff of the Research Seminar, Department of History, A.M.U., Aligarh. I am deeply thankful to my husband Rajeev for his cooperation and constant encouragement in conpleting the present work. I take my responsibility for any mistak. CW-- ^^'~ (SHIVANI SINGH) ALIGARH May'9 5, 3a C O N T E NTS PAGE NO. List of plates i List of Ground Plan iii Introduction 1 Chapter-I t HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 2 Chapter-II: MAIN BUILDINGS INSIDE THE FORT 17 Chapter-Ill; BUILDINGS OUTSIDE THE FORT 45 Chapter-IV; WEST INDIAN ( RAJPUTANA AND GUJARAT ) ARCHITECTURAL INFLUENCE ON THE BUIL DINGS OF FATEHPUR SIKRI. -

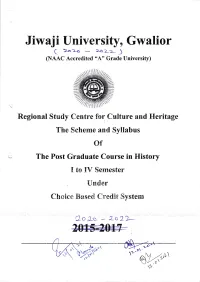

M.A. History (Cbcs) 2020-22

a. Jiwaj i Uxriversi ty, Gwalior e 26 )-o '-'o z-z- ) (NAAC Accredited'0,4," Grade University) Regional Study Centre for Culture amd lleritage The Schenne and Syllabus of ;.. The Post Graduate Course in History tr to IV Sernester Umder Chmice Bl&sesE Cnedi{ Systemr 2o Lt - 2o 2)- i".'"t'ffi'*t rV ffi(IIisrorg v rumrumg - ", rqtS, credjts for each rype-,rE&mnury-..-...-.- u@; 0- |, /l ./ D\ AV ,",,"ffi*, >A' s\r---,,r rr'ot I ^ ZoT\ I \' Resional Studv Centre For Culture & Heritase Jiwaii Universitv. Gwalior Scheme for the Choice Based Credit Svstem. 2015 -2017 M.A. l't Semester (Historv) Sub. Subject Name Credits Code 101 Concept of Historiography (Core) 4 102 l8s Century World (Core) 4 103 Political History of Medieval India (Core) 4 (1320 to 1526 AD) 104 Women in Indian History (Core) 4 105 Seminar I 106 Assignment 1 Total Valid Credits 18 107 Comprehensive Vive -Voce (Virtual Credit) 4 Total Credits = 22 #,€ s-= , V o- SV,, A)' t,'ot m t\' Resional Study Centre For Culture & Heritaee Jiwaii Universitv. Gwalior Scheme for the Choice Based Credit Svstem. 2015 -2017 Sub. Subject Name Credits Code Concept 201 of Historiography (Core) 1 4 202 19" Century World (Core) Y 4 203 Political History of Modem India (Core) 4 (1740 to I 805 AD) 204 History of Marathas (Core) 4 (1627 to 1761 A.D.) Seminar 20s 1 Assignment 206 1 Total Valid Credits 18 207 Comprehensive Vive -Voce (Virtual Credit) 4 Total Credits = 22 (.'{" \ &\ )v,/ 0\i,:, A1' \)., \'r' s6't g,^q .s' , Sub. -

12 the Mughal Empire and Its Successors

ISBN 978-92-3-103876-1 Political history 12 THE MUGHAL EMPIRE AND ITS SUCCESSORS* M. Athar Ali Contents Political history ..................................... 302 The imperial structure .................................. 310 The social and economic framework .......................... 313 High culture ....................................... 315 State and religion .................................... 316 Decline of the empire (1707–1857) ........................... 319 Kashmir, Punjab and Sind under the Mughals and their successors .......... 320 Political history THE MUGHAL EMPIRES FIRST PHASE (1526–40) At the beginning of the sixteenth century India was divided into a number of regional states. Within the area included in Central Asia for the purposes of this volume1 were found the independent principality of Kashmir, the Langah¯ kingdom of Multan (southern Punjab) and the kingdom of Sind under the Jams.¯ Punjab, with its capital at Lahore, was a province of the Lodi empire, which under Sultan¯ Sikandar (1489–1517) extended from the Indus to Bihar. The newly founded city of Agra was the sultan’s capital, while Delhi was in a * See Map 6, p. 930. 1 The term ‘Central Asia’ is used here in the broader sense given to it for the series to which this volume belongs and includes Kashmir and the Indus plains (Punjab and Sind). 302 ISBN 978-92-3-103876-1 Political history state of decay. A large part of the ruling class in the Lodi sultanate consisted of Afghan immigrants, though there was considerable accommodation with local elements. When Zah¯ıru’dd¯ın Muhammad Babur¯ (1483–1530), the Timurid prince celebrated for his memoirs,2 fled from his ancestral principality of Ferghana, he established himself in Kabul in 1504. -

Fairs & Festivals, Part VII-B, Vol-XIV, Rajasthan

PRG. 172 B (N) 1,000 CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME XIV .RAJASTHAN PART VII-B FAIRS & FESTIVALS c. S. GUPTA OF THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE Superintendent of Census Operations, Rajasthan 1966 PREFACE Men are by their nature fond of festivals and as social beings they are also fond of congregating, gathe ring together and celebrating occasions jointly. Festivals thus culminate in fairs. Some fairs and festivals are mythological and are based on ancient traditional stories of gods and goddesses while others commemorate the memories of some illustrious pers<?ns of distinguished bravery or. persons with super-human powers who are now reverenced and idealised and who are mentioned in the folk lore, heroic verses, where their exploits are celebrated and in devotional songs sung in their praise. Fairs and festivals have always. been important parts of our social fabric and culture. While the orthodox celebrates all or most of them the common man usually cares only for the important ones. In the pages that follow an attempt is made to present notes on some selected fairs and festivals which are particularly of local importance and are characteristically Rajasthani in their character and content. Some matter which forms the appendices to this book will be found interesting. Lt. Col. Tod's fascinating account of the festivals of Mewar will take the reader to some one hundred fifty years ago. Reproductions of material printed in the old Gazetteers from time to time give an idea about the celebrations of various fairs and festivals in the erstwhile princely States. Sarva Sbri G.