Identifying Backwardness of Mewat Region in Haryana- a Block Level

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District Wise Skill Gap Study for the State of Haryana.Pdf

District wise skill gap study for the State of Haryana Contents 1 Report Structure 4 2 Acknowledgement 5 3 Study Objectives 6 4 Approach and Methodology 7 5 Growth of Human Capital in Haryana 16 6 Labour Force Distribution in the State 45 7 Estimated labour force composition in 2017 & 2022 48 8 Migration Situation in the State 51 9 Incremental Manpower Requirements 53 10 Human Resource Development 61 11 Skill Training through Government Endowments 69 12 Estimated Training Capacity Gap in Haryana 71 13 Youth Aspirations in Haryana 74 14 Institutional Challenges in Skill Development 78 15 Workforce Related Issues faced by the industry 80 16 Institutional Recommendations for Skill Development in the State 81 17 District Wise Skill Gap Assessment 87 17.1. Skill Gap Assessment of Ambala District 87 17.2. Skill Gap Assessment of Bhiwani District 101 17.3. Skill Gap Assessment of Fatehabad District 115 17.4. Skill Gap Assessment of Faridabad District 129 2 17.5. Skill Gap Assessment of Gurgaon District 143 17.6. Skill Gap Assessment of Hisar District 158 17.7. Skill Gap Assessment of Jhajjar District 172 17.8. Skill Gap Assessment of Jind District 186 17.9. Skill Gap Assessment of Kaithal District 199 17.10. Skill Gap Assessment of Karnal District 213 17.11. Skill Gap Assessment of Kurukshetra District 227 17.12. Skill Gap Assessment of Mahendragarh District 242 17.13. Skill Gap Assessment of Mewat District 255 17.14. Skill Gap Assessment of Palwal District 268 17.15. Skill Gap Assessment of Panchkula District 280 17.16. -

Exhibitions Director Archives Dept

Phone:2561412 rdi I I r 431, SECTOR 2. PANCHKULA-134 112 ; j K.L.Zakir HUA/2006-07/ Secretary Dafeci:")/.^ Subject:-1 Seminar on the "Role of Mewat in the Freedom Struggle'i. Dearlpo ! I The Haryana Urdu Akademi, in collaboration with the District Administration Mewat, proposes to organize a Seminar on the "Role of Mewat in the Freedom Struggle" in the 1st or 2^^ week of November,2006 at Nuh. It is a very important Seminar and everyone has appreciated this proposal. A special meeting was organized a couple of weeks back ,at Nuh. A list ojf the experts/Scholars/persons associated with the families of the freedom fighters was tentatively prepared in that meeting, who could be aiv requ 3Sted to present their papers in the Seminar. Your name is also in this list. therefore, request you to please intimate the title of the paper which you ^ould like to present in the Seminar. The Seminar is expected to be inaugurated by His Excellency the Governor of Haryana on the first day of the Seminar. On the Second day, papers will be presented by the scholars/experts/others and in tlie valedictory session, on the second day, a report of the Seminar will be presented along with the recommendations. I request you to see the possibility of putting up an exhibition during the Seminar at Nuh, in the Y.M.D. College, which would also be inaugurated by His Excellency on the first day and it would remain open for the students of the college ,other educational intuitions and general public, on the second day. -

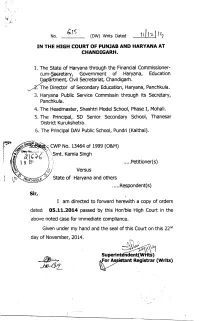

For Assistant Registrar (Writs) -4

s: No. (DW) Writs Dated It11`2-1(1.2 IN THE HIGH COURT OF PUN3AB AND HARYANA AT CHANDIGARH. 1. The State of Haryana through the Financial Commissioner- cum-S- etary, Government of Haryana, Education D•artment, Civil Secretariat, Chandigarh. The Director of Secondary Education, Haryana, Panchkula. Haryana Public Service Commissin through its Secretary, Panchkula. The Headmaster, Shashtri Model School, Phase I, Mohali. The Principal, SD Senior. Secondary School, Thanesar District Kurukshetra. The Principal DAV Public School, Pundri (Kaithal). CWP No. 13464 of 1999 (O&M) Smt. Kamla Singh Petitioner(s) Versus State of Haryana and others Respondent(s) Sir, I am directed to forward herewith a copy of orders dated 05.11.2014 passed by this Hon'ble High Court in the above noted case for immediate compliance. Given under my hand and the seal of this Court on this 22nd day of November, 2014. \\VI Superintendent(W its) For Assistant Registrar (Writs) -4- IN THE HIGH COURT FOR THE STATES OP PUNJAB AND HARYANA AT CHANDIGARH. ti C.W.P.NO ? of 1999. :;mt.. Kamla Singh daughter of Shri Phool Singh, resident of y P 0 Nangal Chaudhary, Tehsil and District Mohindergarh. _Petitioner. versus The State of Haryana through the Financial Commissioner cum Secretary to Govt. of Haryana, Education Department, Civil Secretariat, Sector 17, Chandigarh. 2.. The Director Secondary Education, Haryana, 30 bays building, Sector 17-C, Chandigarh. 3. Haryana Public Service Commission through its Secretary, S.C.O.No, 64-65, Sector 17-A, Chandi- garh. l; 4 Smt. Surnan Devi, Senior Lecturer, D.I.E.T., Palwal, District Kurukshetra. -

Gender and Migration: Negotiating Rights a Women's Movement

CENTRE FOR WOMEN’S DEVELOPMENT STUDIES NEW DELHI Final Technical Report of the Project on Gender and Migration: Negotiating Rights A Women’s Movement Perspective IDRC Grant No. 103978-001 Research Institution: Centre for Women's Development Studies 25 Bhai Vir Singh Marg, New Delhi, India Project Area: India Date January 2012 Supported by: 1 CENTRAL RESEARCH TEAM Project Director Dr. Indu Agnihotri Asst. Project Director Ms. Indrani Mazumdar Dr. Neetha N. Research Associates Ms. Taneesha Devi Mohan Ms. Shruti Chaudhry Administrative Assistance Mr. Nandan Pillai 2 CONTENTS 1 ABSTRACT & KEY WORDS 2 FINAL TECHNICAL REPORT 3 BACKGROUND AND CONCEPT NOTES FOR REGIONAL CONSULTATIONS 4 REGIONAL CONSULTATION REPORTS 5 QUESTIONNAIRES & CODE SHEETS 6 RESEARCH TEAM PAPERS & NOTES 3 ABSTRACT The new knowledge on the experience of women and internal migration in India that has been generated by this research project covers a vast terrain. A consultation process across seven regions has generated a rich resource of papers/presentations that map the gendered migration patterns in different parts of India. The project has devised a new method for assessing women’s work/employment situation in the country through separation of paid and unpaid work in the official macro-data, which has in turn allowed for a construction of a picture of female labour migration, that was hitherto camouflaged by the dominance of marriage migration in the official data. A meso-level survey covering more than 5000 migrants and their households across 20 states in India has demonstrated that migration has led to the concentration of women in a relatively narrow range of occupations/industries. -

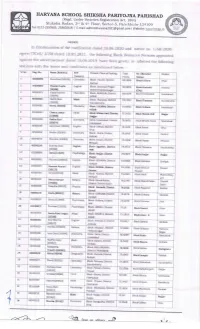

Re-Allocation Orders of Brps Appointed Vide

ORDER In Continuation of the notification clated 25.06.2020 ancl notice no. ll6g-2020- egove/lTCell/ 2350 dated 18'05.202I, the following Block Resource persons appointed against the aclvertisement datecl 15.06.2019 have been given/ re- allottecl the following stations with the terms ancl conditions as rrientioned below :- Sr no. Reg. No, Name No] [Roll BRP Present Place of Posting Total Re- Allocated District (Subiect) Po ints Station 1 80s00090 Renu Rani [50246] Chemistry Block Pundri, District 82.3904 Block Uklana Hisar Kaithal 2 90300003 Sheetal Gupta English Block Saraswati Nagar, 80.5491 Block Ambala-l Ambala [30388] District Yamunanagar (citv) 3 80500379 Vijeta Kumari Chemistry Block AGROHA, District 80.0159 Block Fatehabad Fate ha b ad [50287] HISAR 4 80200521 Kavita Devi Math Block Thanesar, District 19.7555 Block Thanesar Ku ru kshetra [20s0sl Kurukashetra 5 80500082 Neetu [50044] Chemistry Block UKLAN& District 79.0958 Block Tohana Fateha b ad HISAR 6 80100534 Chetna Jathol Hnd Block Matan Hail, District 17.2672 Block Matan Hail Jhajjar [10488] Jhajjar 7 80500239 Rekha Rani Chemistry Block Fatehabad, District 76.9072 Block Bhattu Kalan Fate hab ad Iso274l Fatehab ad 8 80300187 Aarti Devi [30042] Engl ish Block Odhan, Dlstrict 76.s692 Block Rania Sirsa Sirsa 9 80s00265 Shalini Is0294] Chemistry Block Guhla, District 76.O107 Block Siwan Kaithal Kaith al 10 80500243 Manisha [500891 Chemistry Block Siwani, District 75.3908 Block Siwani Bhiwani Bhiwani 11 80300199 Sushma Devi English Block Jagadhri, District t 5.3571 Elock Thanesar -

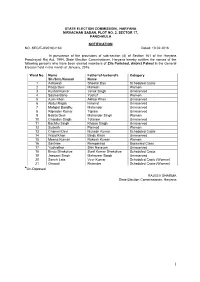

State Election Commission, Haryana Nirvachan Sadan, Plot No

STATE ELECTION COMMISSION, HARYANA NIRVACHAN SADAN, PLOT NO. 2, SECTOR 17, PANCHKULA NOTIFICATION NO. SEC/E-II/2016/2163 Dated: 10.02.2016 In pursuance of the provisions of sub-section (4) of Section 161 of the Haryana Panchayati Raj Act, 1994, State Election Commissioner, Haryana hereby notifies the names of the following persons who have been elected members of Zila Parishad, district Palwal in the General Election held in the month of January, 2016. Ward No. Name Father's/Husband's Category Sh./Smt./Kumari Name 1 Ashawati Sheetal Das Scheduled Caste 2 Pooja Devi Mahesh Women 3 Kushal Kumar Janak Singh Unreserved 4 Sayma Bano Yushuf Women 5 Azim Khan Akhtar Khan Unreserved 6 Abdul Rajjak Himmat Unreserved 7 Mahipal Bandhu Mahender Unreserved 8 Rajender Kumar Tejram Unreserved 9 Babita Devi Mahander Singh Women 10 Chandan Singh Totaram Unreserved 11 Bachhu Singh Khajan Singh Unreserved 12 Sudesh Parmod Women 13 Chameli Devi Mukesh Kumar Scheduled Caste 14 Wajid Khan Bindu Khan Unreserved 15 Meena Kumari Rakesh Kumar Women 16 Santram Ramparsad Backward Class 17 Yudhisther Shiv Narayan Unreserved 18 Bindu Dhakoliya Sunil Kumar Dhakoliya Scheduled Caste 19 Jaswant Singh Mahaveer Singh Unreserved 20 Saneh Lata Veer Kumar Scheduled Caste (Women) 21 Omwati Rajender Scheduled Caste (Women) *Un-Opposed RAJEEV SHARMA State Election Commissioner, Haryana 1 STATE ELECTION COMMISSION, HARYANA NIRVACHAN SADAN, PLOT NO. 2, SECTOR 17, PANCHKULA NOTIFICATION NO. SEC/E-II/2016/2164 Dated: 10.02.2016 In pursuance of the provisions of sub-section (4) of Section 161 of the Haryana Panchayati Raj Act, 1994, State Election Commissioner, Haryana hereby notifies the names of the following persons who have been elected members of Panchayat Samiti Hassanpur, district Palwal in the General Election held in the month of January, 2016. -

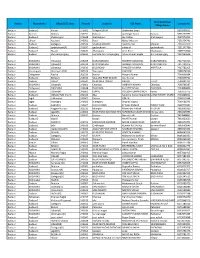

Bareilly Zone CSC List

S Grampanchayat N District Block Name Village/CSC name Pincode Location VLE Name Contact No Village Name o Badaun Budaun2 Kisrua 243601 Village KISRUA Shailendra Singh 5835005612 Badaun Gunnor Babrala 243751 Babrala Ajit Singh Yadav Babrala 5836237097 Badaun Budaun1 shahavajpur 243638 shahavajpur Jay Kishan shahavajpur 7037970292 Badaun Ujhani Nausera 243601 Rural Mukul Maurya 7351054741 Badaun Budaun Dataganj 243631 VILLEGE MARORI Ajeet Kumar Marauri 7351070370 Badaun Budaun2 qadarchowk(R) 243637 qadarchowk sifate ali qadarchowk 7351147786 Badaun Budaun1 Bisauli 243632 dhanupura Amir Khan Dhanupura 7409212060 Badaun Budaun shri narayanganj 243639 mohalla shri narayanganj Ashok Kumar Gupta shri narayanganj 7417290516 Badaun BUDAUN1 Ujhani(U) 243639 NARAYANGANJ SHOBHIT AGRAWAL NARAYANGANJ 7417721016 Badaun BUDAUN1 Ujhani(U) 243639 NARAYANGANJ SHOBHIT AGRAWAL NARAYANGANJ 7417721016 Badaun BUDAUN1 Ujhani(U) 243639 BILSI ROAD PRADEEP MISHRA AHIRTOLA 7417782205 Badaun Vazeerganj Wazirganj (NP) 202526 Wazirganj YASH PAL 7499478130 Badaun Dahgawan Nadha 202523 Nadha Mayank Kumar 7500006864 Badaun Budaun2 Bichpuri 243631 VILL AND POST MIAUN Atul Kumar 7500379752 Badaun Budaun Ushait 243641 NEAR IDEA TOWER DHRUV Ushait 7500401211 Badaun BUDAUN1 Ujhani(R) 243601 Chandau AMBRISH KUMAR Chandau 7500766387 Badaun Dahgawan DANDARA 243638 DANDARA KULDEEP SINGH DANDARA 7534890000 Badaun Budaun Ujhani(R) 243601 KURAU YOGESH KUMAR SINGH Kurau 7535079775 Badaun Budaun2 Udhaiti Patti Sharki 202524 Bilsi Sandeep Kumar ShankhdharUGHAITI PATTI SHARKI 7535868001 -

Executive Summary Block and Village Development Plan, Palwal, Haryana

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Block and Village Development Plan for Palwal, Haryana, 2031 The block and village development plan for Palwal 2031 as a Studio exercise has been taken up in second semester to prepare a sub-regional plan of substantial geographical size having a rural and urban composition. The analysis was carried out in four phases: pre-study, literature survey and identification of villages, field survey comprising of qualitative and quantitative data collection, data analysis data and identification of issues and potentials, followed by formulation of policies and proposals. The study has integrated sectoral and spatial planning approach. Various sectors such as regional setting, demography, economy, traffic and transportation, housing, infrastructure, environment, disaster management, governance and finance are studied. The spatial approach is achieved by dealing with each sector, their spatial distribution and areal differentiation. The interrelationship between each sector and the spatial pattern of development is analyzed. Palwal district being part of National Capital Region (N.C.R.) and Haryana sub-region is proposed as a regional centre in 2021. It serves as a potential region for economic development in Palwal as well as adjoining districts. Moreover, the Dedicated Freight Corridor (D.F.C.) alignment along with Kundli Manesar Palwal (K.M.P.) and Kundli Ghaziabad Palwal (K.G.P.) expressway is passing through Palwal, giving a boost to economic development of the district. This development shall trickle down to rural region for balanced regional development. Hence, a plan is required for inducing uniform development over the space. iii Regional Connectivity: Figure 1: Regional Connectivity of Palwal Block Palwal District is strategically located with respect to the whole NCR and is well connected by both Road and rail network. -

Download This PDF File

ISSN: 2347-7474 International Journal Advances in Social Science and Humanities Available online at: www.ijassh.com RESEARCH ARTICLE Indian Politics Moves from Party Oriented towards Personality Oriented: A Case of Gurgaon Parliamentary Constituency for Upcoming Election 2014 Pratap Singh1, Ashwani Kumar2*, Anil1 1Department of Geography, MD University, Rohtak, India. 2 Department of Geography, Gaur Brahman P.G. College, Rohtak, India. Abstract In Indian politics we see a paradigm shift in recent time. The long existing party oriented politics is facing the stiff competition from personality-oriented politics. The same situation we see in Gurgaon parliamentary constituency in Haryana. Here sitting congress MP Stalwart Rao Inderjeet is contesting on a BJP ticket. He is very famous and a leader of high stature. In a country where the word politician is akin to abuse, he is one of the rare few that command respect. Unlike other politicians, people vote for him, and praise him because of his work. This time the huge traction towards BJP's candidate Rao Inderjeet is not just based on Congress' misgovernance in the state but also because of his personality. His style of functioning as a down-to-earth organisational man will enable him to override not only anti-incumbency but also factionalism. Introduction In Indian politics we see a paradigm shift in About 17 lakh voters will decide the fate of 23 recent time. The long existing party oriented candidates in the fray. Like many other states in politics is facing the stiff competition from India, here too the Narendra Modi wave seems to personality-oriented politics. -

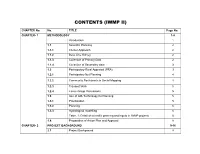

Contents (Iwmp Ii)

CONTENTS (IWMP II) CHAPTER No. No. TITLE Page No. CHAPTER- 1 METHODOLOGY 1-8 Introduction 1 1.1 Scientific Planning 2 1.1.1 Cluster Approach 2 1.1.2 Base Line Survey 2 1.1.3 Collection of Primary Data 2 1.1.4 Collection of Secondary data 3 1.2 Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA) 3 1.2.1 Participatory Net Planning 4 1.2.2 Community Participants in Social Mapping 4 1.2.3 Transect Walk 5 1.2.4 Focus Group Discussions 5 1.3 Use of GIS Technology for Planning 5 1.3.1 Prioritization 5 1.3.2 Planning 6 1.3.3 Hydrological modelling 6 Table. 1: Detail of scientific planning and inputs in IWMP projects 6 1.4 Preparation of Action Plan and Approval 8 CHAPTER- 2 PROJECT BACKGROUND 9-16 2.1 Project Background 9 CHAPTER No. No. TITLE Page No. Table. 1: Basic Project Information 9 2.2 Need of Watershed Development Programme 10 Table. 2: Criteria and Weight Age for Selection of Watershed 11 Table. 3: Weight-age of the Project 13 Table. 4: Watershed Information 14 2.3 Other ongoing Development Projects / Schemes in the project villages 14 Table. 5: Ongoing Developmental Programs in the Project Area 14 Table. 6: Previous Watershed Programme in the Project Area (if any) 16 CHAPTER- 3 BASIC INFORMATION OF THE PROJECT AREA 17-43 Geography And Geo-hydrology 17 3.1 Land Use Pattern 17 Table 1. Land use pattern 17 3.2 Soil and Topography 18 Table 2. Soil type and Topography 18 3.2.1 Flood And Drought Condition 19 Table 3. -

Fairs & Festivals, Part VII-B, Vol-XIV, Rajasthan

PRG. 172 B (N) 1,000 CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME XIV .RAJASTHAN PART VII-B FAIRS & FESTIVALS c. S. GUPTA OF THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE Superintendent of Census Operations, Rajasthan 1966 PREFACE Men are by their nature fond of festivals and as social beings they are also fond of congregating, gathe ring together and celebrating occasions jointly. Festivals thus culminate in fairs. Some fairs and festivals are mythological and are based on ancient traditional stories of gods and goddesses while others commemorate the memories of some illustrious pers<?ns of distinguished bravery or. persons with super-human powers who are now reverenced and idealised and who are mentioned in the folk lore, heroic verses, where their exploits are celebrated and in devotional songs sung in their praise. Fairs and festivals have always. been important parts of our social fabric and culture. While the orthodox celebrates all or most of them the common man usually cares only for the important ones. In the pages that follow an attempt is made to present notes on some selected fairs and festivals which are particularly of local importance and are characteristically Rajasthani in their character and content. Some matter which forms the appendices to this book will be found interesting. Lt. Col. Tod's fascinating account of the festivals of Mewar will take the reader to some one hundred fifty years ago. Reproductions of material printed in the old Gazetteers from time to time give an idea about the celebrations of various fairs and festivals in the erstwhile princely States. Sarva Sbri G. -

States, Scrs & Districts in India

States, SCRs & districts in India 1 www.azresearch.in SCRs overview – by states State / UT SCRs Andaman Andamans AP Andhra, Rayalseema Arunachal Pradesh Arunachal Pradesh Assam Cachar, Brahmaputra Bihar Bhojpur, Maithila, Magadh Chattisgarh Chattisgarh Daman & Diu Saurashtra, GujratPlains Goa Kannada Gujrat Kutch, Surashtra, Plains, Bhilistan Haryana Mewat, Haryana Himachal Himachal Kishtwar & Jammu, Kashmir Valley, J & K Ladakh & Balistan Jharkand Jharkand Karnataka Karnatak, Mysore & Malnad, Kannada Kerala Malabar, Kerala Coastal, Lakshadweep Laccadives 2 www.azresearch.in SCRs overview – by states State / UT SCRs Konkan, Marathwada, Desh, Vidharbha, Maharastra Khandesh Manipur Manipur Meghalaya Meghalaya Mizoram Mizoram Bundelkhand, Baghelkhand, Malwa, MP Bhilistan, Dandekernia Nagaland Nagaland Dandekernia, Chattisgarh, Kalinga, Orissa Orissa Hills & Plateau Punjab Bisht Doab, North Punjab Maru Pradesh, Jaipur, Mewar, Mewat, Rajasthan Bhilistan Sikkim Darjeeling Tamil Nadu Kongunad, Coramandel Tripura Tripura Oudh, Rohelkhand, Braj, Bhojpur, UP Bundelkhand Uttarakhand Uttarakhand West Bengal Ganga Delta, Darjeeling 3 www.azresearch.in SCRs – of India State SCR District Name Barmer (B) Jalor (B) Jaisalmer (B) Nagaur (B) Rajasthan Maru Pradesh Churu (B) Pali Bikaner Jodhpur (B) Ganganagar Sikar (B) Jhunjhunun (B) Sawai Madhopur Rajasthan Jaipur Tonk (B) Ajmer Jaipur Banswara (B) Sirohi (B) Udaipur (B) Rajasthan Mewar Jhalawar (B) Chittaurgarh Bhilwara (B) Bundi 4 www.azresearch.in SCRs – of India State SCR District Name Rajasthan Mewar Kota Alwar (B) Rajasthan Mewat Bharatpur Haryana Gurgaon Rohtak Bhiwani Mahendragarh Jind Hisar Haryana Haryana Sonipat Faridabad Sirsa Ambala Karnal Kurukshetra Chamoli (B) Tehri Garhwal (B) Almora (B) Uttar Kashi (B) U.P. Uttarakhand Garhwal (B) Pithoragarh (B) Nainital (B) Dehra Dun (B) Budaun (B) Muzaffarnagar Bareilly U.P. Rohelkahand Shahjahanpur (B) Rampur (B) Moradabad (B) 5 www.azresearch.in SCRs – of India State SCR District Name Bijnor Pilibhit (B) U.P.