Gender and Migration: Negotiating Rights a Women's Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exhibitions Director Archives Dept

Phone:2561412 rdi I I r 431, SECTOR 2. PANCHKULA-134 112 ; j K.L.Zakir HUA/2006-07/ Secretary Dafeci:")/.^ Subject:-1 Seminar on the "Role of Mewat in the Freedom Struggle'i. Dearlpo ! I The Haryana Urdu Akademi, in collaboration with the District Administration Mewat, proposes to organize a Seminar on the "Role of Mewat in the Freedom Struggle" in the 1st or 2^^ week of November,2006 at Nuh. It is a very important Seminar and everyone has appreciated this proposal. A special meeting was organized a couple of weeks back ,at Nuh. A list ojf the experts/Scholars/persons associated with the families of the freedom fighters was tentatively prepared in that meeting, who could be aiv requ 3Sted to present their papers in the Seminar. Your name is also in this list. therefore, request you to please intimate the title of the paper which you ^ould like to present in the Seminar. The Seminar is expected to be inaugurated by His Excellency the Governor of Haryana on the first day of the Seminar. On the Second day, papers will be presented by the scholars/experts/others and in tlie valedictory session, on the second day, a report of the Seminar will be presented along with the recommendations. I request you to see the possibility of putting up an exhibition during the Seminar at Nuh, in the Y.M.D. College, which would also be inaugurated by His Excellency on the first day and it would remain open for the students of the college ,other educational intuitions and general public, on the second day. -

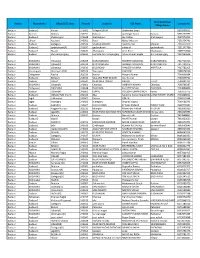

Bareilly Zone CSC List

S Grampanchayat N District Block Name Village/CSC name Pincode Location VLE Name Contact No Village Name o Badaun Budaun2 Kisrua 243601 Village KISRUA Shailendra Singh 5835005612 Badaun Gunnor Babrala 243751 Babrala Ajit Singh Yadav Babrala 5836237097 Badaun Budaun1 shahavajpur 243638 shahavajpur Jay Kishan shahavajpur 7037970292 Badaun Ujhani Nausera 243601 Rural Mukul Maurya 7351054741 Badaun Budaun Dataganj 243631 VILLEGE MARORI Ajeet Kumar Marauri 7351070370 Badaun Budaun2 qadarchowk(R) 243637 qadarchowk sifate ali qadarchowk 7351147786 Badaun Budaun1 Bisauli 243632 dhanupura Amir Khan Dhanupura 7409212060 Badaun Budaun shri narayanganj 243639 mohalla shri narayanganj Ashok Kumar Gupta shri narayanganj 7417290516 Badaun BUDAUN1 Ujhani(U) 243639 NARAYANGANJ SHOBHIT AGRAWAL NARAYANGANJ 7417721016 Badaun BUDAUN1 Ujhani(U) 243639 NARAYANGANJ SHOBHIT AGRAWAL NARAYANGANJ 7417721016 Badaun BUDAUN1 Ujhani(U) 243639 BILSI ROAD PRADEEP MISHRA AHIRTOLA 7417782205 Badaun Vazeerganj Wazirganj (NP) 202526 Wazirganj YASH PAL 7499478130 Badaun Dahgawan Nadha 202523 Nadha Mayank Kumar 7500006864 Badaun Budaun2 Bichpuri 243631 VILL AND POST MIAUN Atul Kumar 7500379752 Badaun Budaun Ushait 243641 NEAR IDEA TOWER DHRUV Ushait 7500401211 Badaun BUDAUN1 Ujhani(R) 243601 Chandau AMBRISH KUMAR Chandau 7500766387 Badaun Dahgawan DANDARA 243638 DANDARA KULDEEP SINGH DANDARA 7534890000 Badaun Budaun Ujhani(R) 243601 KURAU YOGESH KUMAR SINGH Kurau 7535079775 Badaun Budaun2 Udhaiti Patti Sharki 202524 Bilsi Sandeep Kumar ShankhdharUGHAITI PATTI SHARKI 7535868001 -

Fairs & Festivals, Part VII-B, Vol-XIV, Rajasthan

PRG. 172 B (N) 1,000 CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME XIV .RAJASTHAN PART VII-B FAIRS & FESTIVALS c. S. GUPTA OF THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE Superintendent of Census Operations, Rajasthan 1966 PREFACE Men are by their nature fond of festivals and as social beings they are also fond of congregating, gathe ring together and celebrating occasions jointly. Festivals thus culminate in fairs. Some fairs and festivals are mythological and are based on ancient traditional stories of gods and goddesses while others commemorate the memories of some illustrious pers<?ns of distinguished bravery or. persons with super-human powers who are now reverenced and idealised and who are mentioned in the folk lore, heroic verses, where their exploits are celebrated and in devotional songs sung in their praise. Fairs and festivals have always. been important parts of our social fabric and culture. While the orthodox celebrates all or most of them the common man usually cares only for the important ones. In the pages that follow an attempt is made to present notes on some selected fairs and festivals which are particularly of local importance and are characteristically Rajasthani in their character and content. Some matter which forms the appendices to this book will be found interesting. Lt. Col. Tod's fascinating account of the festivals of Mewar will take the reader to some one hundred fifty years ago. Reproductions of material printed in the old Gazetteers from time to time give an idea about the celebrations of various fairs and festivals in the erstwhile princely States. Sarva Sbri G. -

States, Scrs & Districts in India

States, SCRs & districts in India 1 www.azresearch.in SCRs overview – by states State / UT SCRs Andaman Andamans AP Andhra, Rayalseema Arunachal Pradesh Arunachal Pradesh Assam Cachar, Brahmaputra Bihar Bhojpur, Maithila, Magadh Chattisgarh Chattisgarh Daman & Diu Saurashtra, GujratPlains Goa Kannada Gujrat Kutch, Surashtra, Plains, Bhilistan Haryana Mewat, Haryana Himachal Himachal Kishtwar & Jammu, Kashmir Valley, J & K Ladakh & Balistan Jharkand Jharkand Karnataka Karnatak, Mysore & Malnad, Kannada Kerala Malabar, Kerala Coastal, Lakshadweep Laccadives 2 www.azresearch.in SCRs overview – by states State / UT SCRs Konkan, Marathwada, Desh, Vidharbha, Maharastra Khandesh Manipur Manipur Meghalaya Meghalaya Mizoram Mizoram Bundelkhand, Baghelkhand, Malwa, MP Bhilistan, Dandekernia Nagaland Nagaland Dandekernia, Chattisgarh, Kalinga, Orissa Orissa Hills & Plateau Punjab Bisht Doab, North Punjab Maru Pradesh, Jaipur, Mewar, Mewat, Rajasthan Bhilistan Sikkim Darjeeling Tamil Nadu Kongunad, Coramandel Tripura Tripura Oudh, Rohelkhand, Braj, Bhojpur, UP Bundelkhand Uttarakhand Uttarakhand West Bengal Ganga Delta, Darjeeling 3 www.azresearch.in SCRs – of India State SCR District Name Barmer (B) Jalor (B) Jaisalmer (B) Nagaur (B) Rajasthan Maru Pradesh Churu (B) Pali Bikaner Jodhpur (B) Ganganagar Sikar (B) Jhunjhunun (B) Sawai Madhopur Rajasthan Jaipur Tonk (B) Ajmer Jaipur Banswara (B) Sirohi (B) Udaipur (B) Rajasthan Mewar Jhalawar (B) Chittaurgarh Bhilwara (B) Bundi 4 www.azresearch.in SCRs – of India State SCR District Name Rajasthan Mewar Kota Alwar (B) Rajasthan Mewat Bharatpur Haryana Gurgaon Rohtak Bhiwani Mahendragarh Jind Hisar Haryana Haryana Sonipat Faridabad Sirsa Ambala Karnal Kurukshetra Chamoli (B) Tehri Garhwal (B) Almora (B) Uttar Kashi (B) U.P. Uttarakhand Garhwal (B) Pithoragarh (B) Nainital (B) Dehra Dun (B) Budaun (B) Muzaffarnagar Bareilly U.P. Rohelkahand Shahjahanpur (B) Rampur (B) Moradabad (B) 5 www.azresearch.in SCRs – of India State SCR District Name Bijnor Pilibhit (B) U.P. -

442937 1 En Bookbackmatter 225..243

Appendix: How to Obtain Satellite Data from Bhuvan Bhuvan is an Indian Geo-platform (http:// • Click on ‘Metadata’ button for metadata of bhuvan.nrsc.gov.in) developed by the National the corresponding tile. Remote Sensing Centre (NRSC), Indian Space • Click on ‘Download’ button to download the Research Organisation (ISRO). This portal tiles. Login is required for downloading the tiles. allows the users to select and download the • Number of tiles for download has been fixed to geospatial data free of cost based on various data 10 tiles/day for Cartosat-DEM, AWiFs data and search mechanisms like bounding box, tiles 16 tiles/day for LISS-III data. Other tiles can be (1° Â 1° and 15′ Â 15′), interactive drawing and saved in backlog list for future reference. Survey of India mapsheet number on 1:250,000 for AWiFS Ortho and CartoDEM and 1:50,000 United States Geological Survey (USGS) has for LISS-III Ortho scale for India only. Users can two portals to search and download various download Elevation data of CartoDEM-1arc geospatial database at no cost. USGS Earth- second, Resourcesat-1:AWiFs data(56 m) and Explorer (EE) (http://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/)isa LISS-III(24 m) of Indian region from Indian complete search and order tool for aerial photos, Remote sensing Satellite (IRS). normalized dif- elevation data and satellite products distributed by ference vegetation index (NDVI) global cover- the USGS. USGS Global Visualization Viewer age, CartoDem version 3R1 available for South (GloVis) (https://glovis.usgs.gov/) is another portal Asian Association for Regional Cooperation that provides all Landsat 8 OLI/TIRS, Landsat 7 (SAARC) countries and climate product for the ETM+, Landsat 4/5 TM, Landsat 1–5MSS,EO-1 North Indian Ocean. -

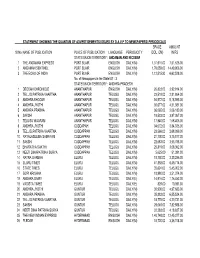

Statement Showing the Quantum of Advertisements

STATEMENT SHOWING THE QUANTUM OF ADVERTISEMENTS ISSUED BY D.A.V.P TO NEWSPAPERS/ PERIODICALS SPACE AMOUNT Sl No NAME OF PUBLICATION PLACE OF PUBLICATION LANGUAGE PERIODICITY (COL .CM) IN RS STATE/UNION TERRITORY : ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 1 THE ANDAMAN EXPRESS PORT BLAIR ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1,31,916.00 7,51,625.00 2 ANDAMAN SENTINEL PORT BLAIR ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1,76,059.00 14,49,906.00 3 THE ECHO OF INDIA PORT BLAIR ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1,12,515.90 6,62,528.00 No. of Newspapers in the State/UT : 3 STATE/UNION TERRITORY : ANDHRA PRADESH 1 DECCAN CHRONICLE ANANTHAPUR ENGLISH DAILY(M) 26,823.00 3,92,914.00 2 TEL.J.D.PATRIKA VAARTHA ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 23,519.00 2,81,864.00 3 ANDHRA BHOOMI ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 54,572.00 5,18,595.00 4 ANDHRA JYOTHI ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 30,677.00 4,31,381.00 5 ANDHRA PRABHA ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 36,065.00 2,06,189.00 6 SAKSHI ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 18,533.00 3,87,367.00 7 TELUGU WAARAM ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 17,940.00 1,68,405.00 8 ANDHRA JYOTHI CUDDAPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 34,072.00 3,84,335.00 9 TEL.J.D.PATRIKA VAARTHA CUDDAPPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 23,566.00 2,68,399.00 10 RAYALASEEMA SAMAYAM CUDDAPPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 21,700.00 3,75,877.00 11 SAKSHI CUDDAPPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 22,683.00 3,95,788.00 12 BHARATHA SAKTHI CUDDAPPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 25,819.00 3,08,362.00 13 NEETI DINAPATRIKA SURYA CUDDAPPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 5,625.00 51,391.00 14 RATNA GARBHA ELURU TELUGU DAILY(M) 18,750.00 3,33,285.00 15 ELURU TIMES ELURU TELUGU DAILY(M) 41,858.00 6,49,774.00 16 STATE TIMES ELURU TELUGU DAILY(M) 35,624.00 -

Annual Report 2012-2013

Annual Report 2012-2013 Annual Report 2012-2013 Empowering women to drive village development INSTITUTE OF RURAL RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT (An initiative of S M Sehgal Foundation) i Annual Report 2012-2013 Contents Message from the Chairman / 1 Policy, Governance and Advocacy /3 Capacity Building / 5 Natural Resource Management / 7 Rural Research / 11 Communications / 13 Resource Mobilization and Partnerships / 15 Crop Improvement / 17 Knowledge Initiatives / 19 Financials / 20 Board and Trustees / 22 Our Team / 24 Interns and Volunteers / 20 ii Annual Report 2012-2013 Message from the Chairman Empowering women to drive village development In today’s rapidly evolving India, rural areas are still marked by enduring poverty, diminishing natural resources, and slow sociocultural progress. IRRAD partners with rural communities to build brighter futures by designing and implementing models in areas vital to village development: water management, small-scale agriculture, and good local governance. At the heart of such endeavors—indeed, at the heart of the families, the farms, the very villages themselves—are the women of rural India. Women are uniquely positioned to drive village development, as they focus on the daily necessities central to the well-being of their families and communities. In this annual report, we feature women’s contributions in planning and monitoring of government programs in their villages and the successes of women farmers. The key to the success and sustainability of rural development initiatives is strong governance at the local level. In 2012-13, we expanded our Good Governance Now initiative to over 400 villages in Mewat district, Haryana, to empower rural citizens to take the lead in the development of their villages. -

The Radiophone Project

The Radiophone Project Technology and Storytelling, Together Changing Rural Children’s Lives “The girls never used to go to school because their job was to herd the cows. After the Radiophone program, the community came together and appointed one person to herd everybody’s cows so that the girls can go to school. I call it cowpooling!” The Radiophone Project An initiative of “Cow-pooling” so that girls can go to school, is one community’s creative response to the dual concerns of female education and keeping the cattle safe. It is also emblematic BACKGROUND of the success of the Radiophone Project, which brings educational content to children and communities that might otherwise have none. Sesame Workshop India’s Galli Galli Sim Sim made its debut on TV in 2006. Each year more than 18 million children watch it regularly on national cable channels - The Galli Galli Sim Sim (GGSS) Radiophone Project, a signature children’s program delivered Pogo and Cartoon Network and national public broadcaster, Doordarshan. GGSS, like its over radio and telephone, is the latest expansion of the Indian adaptation of the popular local Sesame Street counterparts all over the globe, uses the power of media to help children’s show Sesame Street. With its proven education model, GGSS is increasing its reach children reach their highest potential and prepare them for school and for life. and base to include hitherto underserved rural populations. We develop and distribute high-quality and engaging content through television, radio, community radio (CR), print, digital and outreach, to reach children aged zero-eight. -

Identifying Backwardness of Mewat Region in Haryana- a Block Level

Identifying Backwardness of Mewat Region in Haryana: A Block-Level Analysis Study sponsored by: Research Division, NITI Ayog, Government of India Study conducted by: S M Sehgal Foundation, Gurgaon June 2015 DISCLAIMER: “The Institution has received the grants-in-aid under the SER Scheme of the NITI Aayog to produce the document. NITI Aayog is not responsible for findings or opinions expressed in the document prepared. This responsibility rests with the institution”. Table of Contents………………….……………...……………………...………….….……2 List of Tables…………………………………….……………………………….…………..3 List of Figures…………………………………………………………………….………….4 List of Appendix…………………………………………………………………….………..4 Research Team…………………………………………………………………….………...5 Acknowledgement ………………………………………………………………….….…….5 Executive Summary..……………………….……………………………………..…………6 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 11-17 1.1 Background 11 1.2 Objective of the study 12 1.3 Methodology and tools 12 1.4 Structure of the study 15 CHAPTER II LITERATURE REVIEW 18-23 CHAPTER III MULTI-DIMENSIONAL DEVELOPMENT IN MEWAT AND OTHER 24-68 DISTRICTS IN HARYANA: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS 3.1 Mewat: The socio-cultural ethos 24 3.2 Status of development in Mewat: A comparative and temporal analysis 25 3.3 State of development: An intra-state comparison 26 3.3.1 Demographics 27 3.3.2 Standard of Living 31 3.3.3 Education 39 3.3.4 Health 44 3.3.5 Livestock and agriculture 48 3.3.6 Public services and infrastructure 56 3.3.7 Ranking of districts in Haryana 60 3.4 Temporal Transition in Mewat (2001- 2011) 61 3.4.1 Demographic -

MEWAT: a Region That Is Turning Almost Exclusively Muslim at the Core

MEWAT: A region that is turning almost exclusively Muslim at the core Mewat—comprising the newly created Mewat district of Haryana, the adjoining Hathin tahsil of Palwal and several contiguous tahsils of Alwar and Bharatpur districts of Rajasthan—is the homeland of Meo Muslims. They form nearly 50 percent of the population of this region; their presence is above 70 percent in several tahsils and reaches 85 percent in a couple of them. Their growth in all of these tahsils has been very high during the last four decades for which we have compiled the data. Thus, in the five tahsils of the region that fall in Haryana, and which together accommodate more than a million Muslims in 2011, their share in the population has risen from 62 percent in 1971 to 75 percent now. In Pahari tahsil of Bharatpur, their proportion has grown even faster, rising from 63 percent in 1991 to 73 percent in 2011. Every tahsil in the region has experienced a similarly high growth in the presence of Muslims in this period. Unlike the Muslims of Malerkotla in Punjab, who had the protection of the Sikhs around them, the Meos of Mewat had been in active conflict with the Hindus in the decades leading to the Partition, largely because of the spread of the fundamentalist Tablighi movement among them since the last decades of the nineteenth century. There was much disturbance in the region during the Partition and many were displaced from their homes. However, most of them returned after the unrest subsided. They thus retained their dominance in the region. -

Portrait of Population Haryana

CENSUS OF INDIA 1981 A PORTRAIT OF POPULATION HARYANA Draft by S. R. Puri Research Officer Edited by R.K. Aggarwal Deputy Director DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS HARYANA. CHANDIGARH ." I I I tI'- HARVANA ADMINISTRATIVE DIVISIONS 1981 IOUNDARY, DIIT",C1 aoUNb.IUItY, TAHIoIL .,....UCAflrTAl l~HSlL HEAI)QUARTERii -I" • •If- - .. ... 106 0 Ie • 10 .. '" DtsTRICT HEADQUARTERS Nil ALHt TAMIIL HEADQUARTERS . : WHEJlI1M1 DiSTRiCt / T.UtSIL IrIAMI DIFFEIt, FROM ITt HEAOQUAtn'lIIII' 10 6 0 ,. :0 ... 1'mW NAM!. Ttl! 'OR_R "'!"fAD WITHIN .RACKET•• W '**'" I I I ...- .. ..... .. " --..... _-_ _- __ - GANESH After Takia Banwa Faqir Pinjore CONTENTS P"ge FOREWORD v FREFACE vii CHAPTER I Introduction CHAPTER II How many are we? II CHAPTER III Village dwellers and town dwellers 25 CHAPTER IV Are the number of men and women balanc~d? 44 CHAPTER V How many of us can read and write? 50 CHAPTER VI ' , L,anguages we speak 74 CHAPTER VII ' , Religion we follow 78 CHAPTER VIII Scheduled castes and scheduled tribes 89 CHAPTER IX . , How many of us work? 104 CHAPTER X Fertility levels and trends 120 CHAPTER XI " Movement of people 149 CHAPTER XII Summary IW MAPS AND DIAGRAMS Maps 1 Administrative divisions, 1981 Frontispiece 2 Density of population, 1981 Facing page 21 3 Sex ratio, 1981 50 4 Growth of literacy, 1971-81 66 (iii) 5 Main workers, marginal workers and non-workers in total population, 1981 108 II Diagrams 1 Density of population by states, 1981 12 2 Trends in population, 1901-1981 23 3 Percentage of population by size class of villages by districts, 1981 34 4 Urban population by districts, 1971 and 1981 37 5 Towns by size of population, 1981 41 6 Sex ratio, 1901-81 45 7 Population by age-groups, 1981 55 8 Percentage of literacy by states, 1981 61 9 Percentage distribution of population by major religions, 1981 81 10 Distribution of workers, 1981 112 (iv) FOREWORD The Indian Census is now more than hundred years of age. -

To Download Document for More Info

I N D E X Sr. CONTENTS Page No. No. 1. Preface iii 2. History of Backward Classes Movement in Haryana 1–3 3. Acknowledgements 4 4. Identification of Backwards 5 5. Determination of Backward Classes 6–7 6. Central Backward Commission 8–19 7. State Commissions and their recommendations 20–26 8 Constitution of Harayana Backward Classes Commission 27 9 Detail of representations submitted to the Commission 28–28A 10 Format and criteria for determining social, educational, economical 29–35 Backwardness. 11 Estimated Sharing & Breakup of the Sample 36–41 12 Visit by the Commission of various District Headquarters in Haryana to 42–68 hear and ascertain public view 13. Survey Report of Maharishi Dayanand University, Rohtak 69–113 14. Consideration for grant of Reservation 114–148 15. Recommendations of the Commission 149–151 PREFACE A great secular country on the world map is known by different names like ‘India’, ‘Bharat’, ‘Hindustan’, ‘Jambu Deepay Bharat Khandey’. The land of this country is also called as ‘Dev Bhoomi’. Its history is ancient and this land gave birth to great Saints, Scholars, Reformers, and Artisans etc. This country conveyed the message of ‘co-existence’, all over the world. The sword of ‘non-violence’ used by Mahatma Gandhi ‘The Father of the Nation’ to get India free from British Rule is praised all over the world. History is the witness that its rich heritage and hard labour of the people of this country had made this country as ‘Sone ki Chiriya’ which attracted the invaders to rob/ruin and to rule over this country.