Cultivation of Indigo in Medieval India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SYNOPSIS of DEBATE ______(Proceedings Other Than Questions and Answers) ______Friday, March 19, 2021 / Phalguna 28, 1942 (Saka) ______OBSERVATION by the CHAIR 1

RAJYA SABHA _______ SYNOPSIS OF DEBATE _______ (Proceedings other than Questions and Answers) _______ Friday, March 19, 2021 / Phalguna 28, 1942 (Saka) _______ OBSERVATION BY THE CHAIR 1. MR. CHAIRMAN: Hon. Members, I have an appeal to make in view of the reports coming from certain States that the virus pandemic is spreading. So, I only appeal to all the Members of Parliament who are here, who are there in their respective fields to be extra careful. I know that you are all public representatives, You can't live in isolation. At the same time while dealing with people, meeting them or going to your constituency or other areas, be careful. Strictly follow the advice given by the Healthy Ministry, Home Ministry, Central Government as well as the guidelines issued by the State Governments concerned from time to time and see to it that they are followed. My appeal is not only to you, but also to the people in general. The Members of Parliament should take interest to see that the people are guided properly. We are seeing that though the severity has come down, but the cases are spreading here and there. It is because the people in their respective areas are not following discipline. This is a very, very important aspect. We should not allow the situation to deteriorate. We are all happy, the world is happy, the country is happy, people are happy. We have been able to contain it, and we were hoping that we would totally succeed. Meanwhile, these ___________________________________________________ This Synopsis is not an authoritative record of the proceedings of the Rajya Sabha. -

BAYANA the First Lavishly Illustrated and Comprehensive Record of the Historic Bayana Region

BAYANA The first lavishly illustrated and comprehensive record of the historic Bayana region Bayana in Rajasthan, and its monuments, challenge the perceived but established view of the development of Muslim architecture and urban form in India. At the end of the 12th century, early conquerors took the mighty Hindu fort, building the first Muslim city below on virgin ground. They later reconfigured the fort and constructed another town within it. These two towns were the centre of an autonomous region during the 15th and 16th centuries. Going beyond a simple study of the historic, architectural and archaeological remains, this book takes on the wider issues of how far the artistic traditions of Bayana, which developed independently from those of Delhi, later influenced north Indian architecture. It shows how these traditions were the forerunners of the Mughal architectural style, which drew many of its features from innovations developed first in Bayana. Key Features • The first comprehensive account of this historic region • Offers a broad reinvestigation of North Indian Muslim architecture through a case study of a desert fortress MEHRDAD SHOKOOHY • Includes detailed maps of the sites: Bayana Town, the Garden City of NATALIE H. SHOKOOHY Sikandra and the Vijayamandargarh or Tahangar Fort with detailed survey of its fortifications and its elaborate gate systems • Features photographs and measured surveys of 140 monuments and epigraphic records from the 13th to the end of the 16th century – including mosques, minarets, waterworks, domestic dwellings, mansions, ‘īdgāhs (prayer walls) and funerary edifices • Introduces historic outlying towns and their monuments in the region such as Barambad, Dholpur, Khanwa and Nagar-Sikri (later to become Fathpur Sikri) • Demonstrates Bayana’s cultural and historic importance in spite of its present obscurity and neglect BAYANA • Adds to the record of India’s disappearing historic heritage in the wake of modernisation. -

Chronicles of Rajputana: the Valour, Sacrifices and Uprightness of Rajputs

Quest Journals Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Science Volume 9 ~ Issue 8 (2021)pp: 15-39 ISSN(Online):2321-9467 www.questjournals.org Research Paper Chronicles of Rajputana: the Valour, Sacrifices and uprightness of Rajputs Suman Lakhani ABSTRACT Many famous kings and emperors have ruled over Rajasthan. Rajasthan has seen the grandeur of the Rajputs, the gallantry of the Mughals, and the extravagance of Jat monarchs. None the less history of Rajasthan has been shaped and molded to fit one typical school of thought but it holds deep secrets and amazing stories of splendors of the past wrapped in various shades of mysteries stories. This paper is an attempt to try and unearth the mysteries of the land of princes. KEYWORDS: Rajput, Sesodias,Rajputana, Clans, Rana, Arabs, Akbar, Maratha Received 18 July, 2021; Revised: 01 August, 2021; Accepted 03 August, 2021 © The author(s) 2021. Published with open access at www.questjournals.org Chronicles of Rajputana: The Valour, Sacrifices and uprightness of Rajputs We are at a fork in the road in India that we have traveled for the past 150 years; and if we are to make true divination of the goal, whether on the right hand or the left, where our searching arrows are winged, nothing could be more useful to us than a close study of the character and history of those who have held supreme power over the country before us, - the waifs.(Sarkar: 1960) Only the Rajputs are discussed in this paper, which is based on Miss Gabrielle Festing's "From the Land of the Princes" and Colonel James Tod's "Annals of Rajasthan." Miss Festing's book does for Rajasthan's impassioned national traditions and dynastic records what Charles Kingsley and the Rev. -

Module 1A: Uttar Pradesh History

Module 1a: Uttar Pradesh History Uttar Pradesh State Information India.. The Gangetic Plain occupies three quarters of the state. The entire Capital : Lucknow state, except for the northern region, has a tropical monsoon climate. In the Districts :70 plains, January temperatures range from 12.5°C-17.5°C and May records Languages: Hindi, Urdu, English 27.5°-32.5°C, with a maximum of 45°C. Rainfall varies from 1,000-2,000 mm in Introduction to Uttar Pradesh the east to 600-1,000 mm in the west. Uttar Pradesh has multicultural, multiracial, fabulous wealth of nature- Brief History of Uttar Pradesh hills, valleys, rivers, forests, and vast plains. Viewed as the largest tourist The epics of Hinduism, the Ramayana destination in India, Uttar Pradesh and the Mahabharata, were written in boasts of 35 million domestic tourists. Uttar Pradesh. Uttar Pradesh also had More than half of the foreign tourists, the glory of being home to Lord Buddha. who visit India every year, make it a It has now been established that point to visit this state of Taj and Ganga. Gautama Buddha spent most of his life Agra itself receives around one million in eastern Uttar Pradesh, wandering foreign tourists a year coupled with from place to place preaching his around twenty million domestic tourists. sermons. The empire of Chandra Gupta Uttar Pradesh is studded with places of Maurya extended nearly over the whole tourist attractions across a wide of Uttar Pradesh. Edicts of this period spectrum of interest to people of diverse have been found at Allahabad and interests. -

7 Battles of Mughal Army

Battles of Mughal Army Module - II Military History of Medieval India 7 BATTLES OF MUGHAL ARMY Note In the previous lesson, you studied the factors that encouraged Babur to invade India, composition of the Mughal Army and their war equipment and weapons. You also learnt that the Mughal artillery was a new weapon of war and terrifying to the enemies. The gunpowder played a vital role in winning battles and in the establishment and expansion of the Mughal empire. In this lesson, you will study the three important battles fought by Babur which laid a solid foundation of the Mughal rule in India. Panipat (a town in Haryana) has been described as the pivot of Indian history for 300 years. And its story begins in the first great battle that took place in 1526. The victory at Panipat, significant as it was, did not allow Babur the luxury to sit back and savour the moment for long. For there were other enemies such as that of Rana Sanga, the powerful ruler of Mewar to be subdued in land called Hindustan. After capturing Delhi, Babur lived for only four more years. His son Humayun and grandson Akbar continued the consolidation of Mughal power after his death. Although Mughal influence reached its political peak during Akbar's time, the foundation was laid by Akbar's grandfather. Objectives After studing this lesson you will be able to: explain the first battle of Panipat and battle field tactics of the Mughals and discuss the power-struggle that existed during the early years of the Mughal Dynasty. -

The Architecture of Fatehpur Sikri

THE ARCHITECTURE OF FATEHPUR SIKRI Dissertation Submitted for the Degree of M. Phil. BY SHIVANI SINGH Under the Supervision of DR. J. V. SINGH AGRE CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) MAY, 1995 DS2558 ,i.k *i' ••J-jfM/fjp ^6"68 V :^;j^^»^ 1 6 FEB W(> ;»^ j IvJ /\ S.'D c;v^•c r/vu ' x/ ^-* 3 f«d In Coflnp«< CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY TELEPHONE : 5546 DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH, U.P. M«r 31, 1995 Thl« Is to certify that tiM M.Phil 4iM«rt«tion •Btitlad* *Arca>lt<ictar« of FstrtaHir aikri* miikm±ttmd by Mrs. Shlvonl ftlagti 1» Iwr odgi&al woxk and is soitsbls for sulMiiisslon. T (J«g^ Vlr Slagh Agrs) >8h«x«s* • ****•**********."C*** ******* TO MY PARENTS ** **lr*******T*************** ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I wish to express my profound gratitude to my supervisor Dr. J.V, Singh Agre for his unstinted guid ance, valuable suggestions and critical analysis of the present study. I am also grateful to- a) The Chairman, Department of Histoiry, A,i-i.u., Aligarh, b) The ICHR for providing me financial assistance and c) Staff of the Research Seminar, Department of History, A.M.U., Aligarh. I am deeply thankful to my husband Rajeev for his cooperation and constant encouragement in conpleting the present work. I take my responsibility for any mistak. CW-- ^^'~ (SHIVANI SINGH) ALIGARH May'9 5, 3a C O N T E NTS PAGE NO. List of plates i List of Ground Plan iii Introduction 1 Chapter-I t HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 2 Chapter-II: MAIN BUILDINGS INSIDE THE FORT 17 Chapter-Ill; BUILDINGS OUTSIDE THE FORT 45 Chapter-IV; WEST INDIAN ( RAJPUTANA AND GUJARAT ) ARCHITECTURAL INFLUENCE ON THE BUIL DINGS OF FATEHPUR SIKRI. -

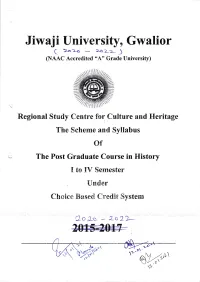

M.A. History (Cbcs) 2020-22

a. Jiwaj i Uxriversi ty, Gwalior e 26 )-o '-'o z-z- ) (NAAC Accredited'0,4," Grade University) Regional Study Centre for Culture amd lleritage The Schenne and Syllabus of ;.. The Post Graduate Course in History tr to IV Sernester Umder Chmice Bl&sesE Cnedi{ Systemr 2o Lt - 2o 2)- i".'"t'ffi'*t rV ffi(IIisrorg v rumrumg - ", rqtS, credjts for each rype-,rE&mnury-..-...-.- u@; 0- |, /l ./ D\ AV ,",,"ffi*, >A' s\r---,,r rr'ot I ^ ZoT\ I \' Resional Studv Centre For Culture & Heritase Jiwaii Universitv. Gwalior Scheme for the Choice Based Credit Svstem. 2015 -2017 M.A. l't Semester (Historv) Sub. Subject Name Credits Code 101 Concept of Historiography (Core) 4 102 l8s Century World (Core) 4 103 Political History of Medieval India (Core) 4 (1320 to 1526 AD) 104 Women in Indian History (Core) 4 105 Seminar I 106 Assignment 1 Total Valid Credits 18 107 Comprehensive Vive -Voce (Virtual Credit) 4 Total Credits = 22 #,€ s-= , V o- SV,, A)' t,'ot m t\' Resional Study Centre For Culture & Heritaee Jiwaii Universitv. Gwalior Scheme for the Choice Based Credit Svstem. 2015 -2017 Sub. Subject Name Credits Code Concept 201 of Historiography (Core) 1 4 202 19" Century World (Core) Y 4 203 Political History of Modem India (Core) 4 (1740 to I 805 AD) 204 History of Marathas (Core) 4 (1627 to 1761 A.D.) Seminar 20s 1 Assignment 206 1 Total Valid Credits 18 207 Comprehensive Vive -Voce (Virtual Credit) 4 Total Credits = 22 (.'{" \ &\ )v,/ 0\i,:, A1' \)., \'r' s6't g,^q .s' , Sub. -

12 the Mughal Empire and Its Successors

ISBN 978-92-3-103876-1 Political history 12 THE MUGHAL EMPIRE AND ITS SUCCESSORS* M. Athar Ali Contents Political history ..................................... 302 The imperial structure .................................. 310 The social and economic framework .......................... 313 High culture ....................................... 315 State and religion .................................... 316 Decline of the empire (1707–1857) ........................... 319 Kashmir, Punjab and Sind under the Mughals and their successors .......... 320 Political history THE MUGHAL EMPIRES FIRST PHASE (1526–40) At the beginning of the sixteenth century India was divided into a number of regional states. Within the area included in Central Asia for the purposes of this volume1 were found the independent principality of Kashmir, the Langah¯ kingdom of Multan (southern Punjab) and the kingdom of Sind under the Jams.¯ Punjab, with its capital at Lahore, was a province of the Lodi empire, which under Sultan¯ Sikandar (1489–1517) extended from the Indus to Bihar. The newly founded city of Agra was the sultan’s capital, while Delhi was in a * See Map 6, p. 930. 1 The term ‘Central Asia’ is used here in the broader sense given to it for the series to which this volume belongs and includes Kashmir and the Indus plains (Punjab and Sind). 302 ISBN 978-92-3-103876-1 Political history state of decay. A large part of the ruling class in the Lodi sultanate consisted of Afghan immigrants, though there was considerable accommodation with local elements. When Zah¯ıru’dd¯ın Muhammad Babur¯ (1483–1530), the Timurid prince celebrated for his memoirs,2 fled from his ancestral principality of Ferghana, he established himself in Kabul in 1504. -

Inclusive Revitalisation of Historic Towns and Cities

GOVERNMENT OF RAJASTHAN Public Disclosure Authorized INCLUSIVE REVITALISATION OF HISTORIC TOWNS AND CITIES Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized STRATEGIC FRAMEWORK FOR RAJASTHAN STATE HERITAGE PROGRAMME 2018 National Institute of Urban Affairs Public Disclosure Authorized All the recorded data and photographs remains the property of NIUA & The World Bank and cannot be used or replicated without prior written approval. Year of Publishing: 2018 Publisher NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF URBAN AFFAIRS, NEW DELHI Disclaimer While every effort has been made to ensure the correctness of data/ information used in this report, neither the authors nor NIUA accept any legal liability for the accuracy or inferences drawn from the material contained therein or for any consequences arising from the use of this material. No part of this report may be reproduced in any form (electronic or mechanical) without prior permission from NIUA and The World Bank. Depiction of boundaries shown in the maps are not authoritative. The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on these maps do not imply official endorsement or acceptance. These maps are prepared for visual and cartographic representation of tabular data. Contact National Institute of Urban Affairs 1st and 2nd floor Core 4B, India Habitat Centre, Lodhi Road, New Delhi 110003 India Website: www.niua.org INCLUSIVE REVITALISATION OF HISTORIC TOWNS AND CITIES STRATEGIC FRAMEWORK FOR RAJASTHAN STATE HERITAGE PROGRAMME 2018 GOVERNMENT OF RAJASTHAN National Institute of Urban Affairs Message I am happy to learn that Department of Local Self Government, Government of Rajasthan has initiated "Rajasthan State Heritage Programme" with technical assistance from the World Bank, Cities Alliance and National Institute of Urban Affairs. -

Unpaid Unclaimed Master 2008-2013

DFM FOODS LIMITED DETAILS OF UNPAID/UNCLAIMED DIVIDEND 2011 - 12 First Name Middle Name Last Name Father/Husband First Father/Husband Father/Husband Last Name Address Country State District PINCode Folio Number of Securities Investment Type Amount Due(in Proposed Date of transfer Name Middle Name Rs.) to IEPF (DD-MON-YYYY) SUTAN SINGH YADAV SH RAM AVTARSINGHYADAV F-361 Nanak Pura N Delhi INDIA Delhi 110021 00000091 Amount for 250.00 03-OCT-2019 Unclaimed and Unpaid Dividend RAJ KUMAR SHARMA SIYA RAM SHARMA H No 366 Sec 8 Vidhyadhar INDIA Rajasthan 302003 00000092 Amount for 500.00 03-OCT-2019 Nagar Jaipur Unclaimed and Unpaid Dividend NARESH KUMAR PATHAK S N PATHAK 58/d Block Kidwai Nagar Kanpur INDIA Uttar Pradesh 208011 00000094 Amount for 500.00 03-OCT-2019 Unclaimed and Unpaid Dividend JAMIR CHAND RANA RAM SINGH RANA H.no. 163, Gali No.-10 P O INDIA Delhi 110042 00000115 Amount for 500.00 03-OCT-2019 Samaipur Swaroop Nagar Delhi Unclaimed and Unpaid Dividend ANIL MARWAHA KASTURILAL NA 27 Pocket 5 Sec 2 Rohini Delhi INDIA Delhi 110085 00000116 Amount for 250.00 03-OCT-2019 Unclaimed and Unpaid Dividend AJAY MALHOTRA BHAGAT RMA GUPTA Jawala Flour Mills 33 Rama INDIA Delhi 110015 00000159 Amount for 500.00 03-OCT-2019 Road N Delhi Unclaimed and Unpaid Dividend JAGDISH PRASAD SAINI MANGAL SINGH SAINI 4057 Gali School Wali Pahari INDIA Delhi 110006 00000175 Amount for 500.00 03-OCT-2019 Dhiraj Delh Unclaimed and Unpaid Dividend KAMENDER SINGH DAL CHAND SINGH Jawala Flour Mills 33 Shivaji INDIA Delhi 110015 00000213 Amount for 500.00 03-OCT-2019 -

(B.Sc.) SUBJECT MILITARY STUDIES OR DEFENCE and STRATEGIC

DR. BHIM RAO AMBEDKAR UNIVERSITY, AGRA . BACHELOR OF SCIENCE (B.Sc.) (THREE YEAR DEGREE COURSE) SUBJECT MILITARY STUDIES OR DEFENCE AND STRATEGIC STUDIES PAGE 1 DR. BHIM RAO AMBEDKAR UNIVERSITY, AGRA . B.Sc. (DEFENCE AND STRATEGIC STUDIES) The entire curriculum is to be divided into four units and each question paper will have: 1. First question – compulsory- Comprising of TEN Short Answer Questions (1 to X) covering the entire curriculum. This question will carry 40% marks of the total marks. 2. The rest of the question paper will be divided into Four Units, comprising of Two questions in each unit. Therefore, the total number of question in each paper shall be NINE. 3. Student will have to attempt one question from each unit. 4. All these (Four) questions will be of equal marks and will carry 60% marks of the total marks. 5. The minimum passing marks in each paper shall be 33% of the total marks. The candidate has to pass theory and practical separately. Total passing percentage (aggregate) to obtain the degree shall be 36%. 6. In the part I and II, there shall be two theory papers and one practical. Maximum marks shall be 35/50 for B.A. and B.Sc. respectively. For practical, it shall be 30/50 marks for BA and B.Sc. respectively. 7. In Part III there shall be three theory papers and one practical maximum marks shall be 35/50 for B.A. and B.Sc. respectively. For Practical, its shall be 45/75 marks for B.A. and B.Sc. -

Abu Road Agar Malwa Agra

ABU ROAD SHOE MARKET SANJAY PLACE (BE HIND DOC TOR SOAP BUILD ING)-282002 ALOK RINKAL & AS SO CI ATES 018770C ALOK MITTAL 411774 1 ABU ROAD RINKAL MITTAL 411955 1 A J S R & AS SO CI ATES 020881C ATUL GOYAL 534034 1 A J P & AS SO CI ATES 137050W MOHIT AGARWAL 408406 1 7 INDRA COL ONY SHOP NO 4 UP PER GROUND FLOOR MAYANK JINDAL 421932 1 BHOGIPURA KAVITA COM PLEX * RAJESH KUMAR SINGH 424068 1 SHAHGANJ-282010 788/1 SECTOR-7 OPP BUS STAND Also at NEW DELHI AVAS VIKAS COLONY SIROHI-307026 SIKANDRA-282007 Head Of fice at MUMBAI Also at SECTOR 4 - A/156 ALOK VRITIK & CO 010344C EWS AVAS VIKAS COLONY 15 NEHRU NAGAR-282002 BODLA-282007 A P SANZGIRI & CO 116293W Head Of fice at MEERUT Also at A-30 RIICO COL ONY-307026 VIL LAGE LOKHARERA Head Of fice at MUMBAI POST RUNKATA-282007 AMBIKA PRASAD SHARMA & CO 007127C AMBIKA PRASAD SHARMA 072542 1 SURBHI JAIN 423003 1 022256C AGARWAL A R & AS SO CI ATES A K HAJELA & CO 000901C 6 NEHRU NAGAR-282002 * RAKESH AGRAWAL 176586 1 HAJELA ADITYA KUMAR 070377 1 * RONAK AGARWAL 433088 1 HAJELA AMAR KANT 070380 1 F 4 FIRST FLOOR ROOM NO 9 2ND FLOOR DEV COMPLEX RAJENDRA MARKET ANAND RAJENDRA & CO 324092E AMBAJI ROAD-307026 HOS PI TAL ROAD-282003 C/O ANIL KUMAR JAIN Also at AHMEDABAD 39/77 NEW IDGAH COL ONY SIROHI NEAR DEVIKAMANDIR UTTAR PRADESH-282001 Head Of fice at KOLKATA ADIWISE M K & AS SO CI ATES 007180N 3/29 PRATAP PURA-282001 CHOUDHARY AMIT & AS SO CI ATES 020192C Head Of fice at JHAJJAR AMIT CHOUDHARY 427238 1 * DHARMENDRA KUMAR SHARMA 429301 1 ANCHAL JAIN & AS SO CI ATES 017959C KANISHKA SHARMA 433597 1