Agra-Fathpur Sikri-Shahjahanabad*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SYNOPSIS of DEBATE ______(Proceedings Other Than Questions and Answers) ______Friday, March 19, 2021 / Phalguna 28, 1942 (Saka) ______OBSERVATION by the CHAIR 1

RAJYA SABHA _______ SYNOPSIS OF DEBATE _______ (Proceedings other than Questions and Answers) _______ Friday, March 19, 2021 / Phalguna 28, 1942 (Saka) _______ OBSERVATION BY THE CHAIR 1. MR. CHAIRMAN: Hon. Members, I have an appeal to make in view of the reports coming from certain States that the virus pandemic is spreading. So, I only appeal to all the Members of Parliament who are here, who are there in their respective fields to be extra careful. I know that you are all public representatives, You can't live in isolation. At the same time while dealing with people, meeting them or going to your constituency or other areas, be careful. Strictly follow the advice given by the Healthy Ministry, Home Ministry, Central Government as well as the guidelines issued by the State Governments concerned from time to time and see to it that they are followed. My appeal is not only to you, but also to the people in general. The Members of Parliament should take interest to see that the people are guided properly. We are seeing that though the severity has come down, but the cases are spreading here and there. It is because the people in their respective areas are not following discipline. This is a very, very important aspect. We should not allow the situation to deteriorate. We are all happy, the world is happy, the country is happy, people are happy. We have been able to contain it, and we were hoping that we would totally succeed. Meanwhile, these ___________________________________________________ This Synopsis is not an authoritative record of the proceedings of the Rajya Sabha. -

History of Mughal Architecture Vol.1

GOVERI\ll\/IEI\iT OF iP^DIA H B Central Archaeological Library Archaeological Survey of India JANPATH, NEW DELHI. Accession No. c. K '7^' ' 3 3 'I Call No. GI'^ f HISTORY OF MHGIIAL ARci n ri-:cTTRr: ISBN 0-3^1-02650-X First Published in India 1982 © R Nath All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any former by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photo- copying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publishers JacViet & inside design; Yashodamohan Colour Plates Printed byD. K. Fine Arts Press, New Delhi Publishers Shakti Malik Abhinav Publications E-37, Hauz Khas, New Delhi-1 10016 Printers Hans Raj Gupta & Sons Anand Parbat New Delhi-110005 A B H i N A V abhiNQv pubLicoiioNs PubtiC AlioNS HISTORY Ol' MUGHAL VOL.l R NATH fibril ' -•.% hwit -~ <T»rt»:i3a TO BABUR The King and the Prince of Gardens whose advent in India marks the dawn of one of the most glorious epochs of Indian History; The Poet and the Aesthete who possessed an extraordinary aesthetic outlook of life which in due course became one of the distinctive characteristics of Mughal Culture; and The Dervish: “Darvishan-ra agar neh az khwaishanem; Lek az dil-o-jan mautqid aishanem; Dur-ast makoi shahi az dervaisti; Shahim vali bandah darvaishanem.” Babur Preface This is first volume of the A-wolume series: HISTORY OF MUGHAL ARCHITECTURE. It aspires to make a stylistic study of the monu- ments (mosques, tombs, gardens, palaces and other buildings) of Babur and Humayun and also includes those which were built at Delhi during the first two decades of Akbar’s reign but did not belong to his style (a list of principal buildings included in the study is given). -

BAYANA the First Lavishly Illustrated and Comprehensive Record of the Historic Bayana Region

BAYANA The first lavishly illustrated and comprehensive record of the historic Bayana region Bayana in Rajasthan, and its monuments, challenge the perceived but established view of the development of Muslim architecture and urban form in India. At the end of the 12th century, early conquerors took the mighty Hindu fort, building the first Muslim city below on virgin ground. They later reconfigured the fort and constructed another town within it. These two towns were the centre of an autonomous region during the 15th and 16th centuries. Going beyond a simple study of the historic, architectural and archaeological remains, this book takes on the wider issues of how far the artistic traditions of Bayana, which developed independently from those of Delhi, later influenced north Indian architecture. It shows how these traditions were the forerunners of the Mughal architectural style, which drew many of its features from innovations developed first in Bayana. Key Features • The first comprehensive account of this historic region • Offers a broad reinvestigation of North Indian Muslim architecture through a case study of a desert fortress MEHRDAD SHOKOOHY • Includes detailed maps of the sites: Bayana Town, the Garden City of NATALIE H. SHOKOOHY Sikandra and the Vijayamandargarh or Tahangar Fort with detailed survey of its fortifications and its elaborate gate systems • Features photographs and measured surveys of 140 monuments and epigraphic records from the 13th to the end of the 16th century – including mosques, minarets, waterworks, domestic dwellings, mansions, ‘īdgāhs (prayer walls) and funerary edifices • Introduces historic outlying towns and their monuments in the region such as Barambad, Dholpur, Khanwa and Nagar-Sikri (later to become Fathpur Sikri) • Demonstrates Bayana’s cultural and historic importance in spite of its present obscurity and neglect BAYANA • Adds to the record of India’s disappearing historic heritage in the wake of modernisation. -

The Role of Poetry Readings in Dispelling the Notion That Urdu Is a Muslim Language

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 4, No. 10; August 2014 The Role of Poetry Readings in Dispelling the Notion that Urdu is a Muslim Language Hiba Mirza G-1, Maharani Bagh New Delhi – 110 065 India Abstract Looking at the grim scenario of the future of Urdu in India, and its overwhelming identification with a particular community (i.e., Muslims) have indeed contributed in creating a narrow image of sectarian interests. However, the concern of the intellectuals about its declining trend, seems to be melting, if we take the case of Mushaira (poetic symposium). Through interviews with both the organisers and the attendees of Delhi Mushairas I collected a serious of impressions that speak to the role of a Mushaira in advancing a cosmopolitan, rather than a communal image of Urdu. Uniting people through poetry, mushairas temporarily dissolve differences of caste, creed and religion. Keywords: Urdu, Narrow image, declining, communal, cosmopolitan Urdu hai mera naam, main Khusro ki paheli Main Meer ki humraaz hun, Ghalib ki saheli My name is Urdu and I am Khusro’s riddle I am Meer’s confidante and Ghalib’s friend Kyun mujhko banate ho ta’assub ka nishana, Maine to kabhi khudko musalma’an nahin maana Why have you made me a target of bigotry? I have never thought myself a Muslim Dekha tha kabhi maine bhi khushiyon ka zamaana Apne hi watan mein hun magar aaj akeli I too have seen an era of happiness But today I am an orphan in my own country - Iqbal Ashar - (Translation by Rana Safvi) 1.0 Introduction India is a pluralistic society. -

ANSWERED ON:23.08.2007 HISTORICAL PLACES in up Verma Shri Bhanu Pratap Singh

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA CULTURE LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:1586 ANSWERED ON:23.08.2007 HISTORICAL PLACES IN UP Verma Shri Bhanu Pratap Singh Will the Minister of CULTURE be pleased to state: (a) the details of Centrally protected monuments in Uttar Pradesh (UP) at present; (b) the agency responsible for the maintenance of these places; (c) the amount spent on the maintenance of these monuments during the last three years; and (d) the details of revenue earned from these monuments during each of the last three years? Answer MINISTER FOR TOURISM AND CULTURE (SHRIMATI AMBIKA SONI) (a)&(b) There are 742 monuments/sites declared as of national importance in the Uttar Pradesh (U.P.) as per list at Annexure. Archaeological Survey of India looks after their proper upkeep, maintenance, conservation and preservation. (c) The expenditure incurred on conservation, preservation, maintenance and environmental development of these centrally protected monuments during the last three years is as under: Rupees in Lakhs Year Total 2004-05 1392.48 2005-06 331.14 2006-07 1300.36 (d) The details of revenue earned from these monuments during the last three years are as under: Rupees in Lakhs Year Total 2004-05 2526.33 2005-06 2619.92 2006-07 2956.46 ANNEXURE ANNEXURE REFERRED TO IN REPLY TO PART (a)&(b) OF THE LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTIO NO.1586 FOR 23.8.2007 LIST OF CENTRALLY PROTECTED MONUMENTS IN UTTAR PRADESH Agra Circle Name of monument/site Locality District 1. Agra Fort Including Akbari Mahal Agra Agra Anguri Bagh Baoli of the Diwan-i-Am Quadrangle. -

(Cemp) for Taj Trapezium Zone (Ttz) Area

FINAL REPORT COMPREHENSIVE ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT PLAN (CEMP) FOR TAJ TRAPEZIUM ZONE (TTZ) AREA Sponsor Agra Development Authority (ADA) AGRA CSIR-National Environmental Engineering Research Institute (NEERI), Nehru Marg, Nagpur - 440 020 (India December, 2013 Table of Contents S.No. Contents Page No. Chapter 1 1.0 Introduction 1.1 1.1 Taj Trapezium Zone (TTZ), Agra – Status and Chronology 1.1 of Events 1.2 Hon’ble Supreme Court Orders (Air Pollution Control) 1.4 1.3 Present Study 1.4 1.3.1 Study Area 1.5 1.3.2 Scope of the Work 1.5 1.3.3 Study Methodology and Report 1.6 Chapter 2 2.0 Air Environment 2.1 2.1 Present Status of Air Environment In TTZ Area 2.1 2.1.1 Air Quality Status Of Agra City 2.1 2.1.1.1 Analysis of Air Quality Data (CPCB) 2.2 2.1.1.2 Annual Variation In AQ Levels 2.3 2.1.1.3 Analysis of Air Quality Data (UPPCB) 2.5 2.1.1.4 Analysis of Air Quality Data (ASI) 2.5 2.1.1.5 Monthly Mean Values At Uppcb Monitoring Stations (2011) 2.6 2.1.1.6+ Monthly Variation In Air Quality Data Measured Using 2.6 Continuous Analyzer 2.1.2 Air Quality Status of Firozabad City 2.8 2.1.3 Air Quality Status of Mathura City 2.9 2.1.4 Air Quality Status of Bharatpur City 2.11 2.2 Meteorology of The Region 2.13 2.2.1 Analysis of Meteorological Data 2.13 2.3 Sources of Air Pollution In TTZ Area 2.13 2.3.1 Industrial Sources 2.13 2.3.2 Vehicular Sources 2.15 2.3.2.1 Traffic Count at Important Locations 2.17 2.3.3 Status Of DG Sets in TTZ Area 2.20 2.3.3.1 Status of DG Sets in Agra 2.20 2.3.3.2 Status of DG Sets in Firozabad 2.21 2.3.3.3 Status of DG Sets in Mathura 2.22 2.4 Air Quality Management Plans 2.23 2.4.1 Summary of Air Quality Of Taj Mahal and in TTZ Area 2.23 2.4.2 Measures taken in Past for Improvement in Air Quality of TTZ 2.24 2.4.3 Road Networks and Traffic Management 2.25 2.4.4 Vehicle Inspection And Maintenance Related Aspects 2.25 Table of Contents (Contd.) S.No. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" X 9" black and w h itephotographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Accessing the World'sUMI Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8824569 The architecture of Firuz Shah Tughluq McKibben, William Jeffrey, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1988 Copyright ©1988 by McKibben, William Jeflfrey. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 PLEASE NOTE: In all cases this material has been filmed in the best possible way from the available copy. -

Chronicles of Rajputana: the Valour, Sacrifices and Uprightness of Rajputs

Quest Journals Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Science Volume 9 ~ Issue 8 (2021)pp: 15-39 ISSN(Online):2321-9467 www.questjournals.org Research Paper Chronicles of Rajputana: the Valour, Sacrifices and uprightness of Rajputs Suman Lakhani ABSTRACT Many famous kings and emperors have ruled over Rajasthan. Rajasthan has seen the grandeur of the Rajputs, the gallantry of the Mughals, and the extravagance of Jat monarchs. None the less history of Rajasthan has been shaped and molded to fit one typical school of thought but it holds deep secrets and amazing stories of splendors of the past wrapped in various shades of mysteries stories. This paper is an attempt to try and unearth the mysteries of the land of princes. KEYWORDS: Rajput, Sesodias,Rajputana, Clans, Rana, Arabs, Akbar, Maratha Received 18 July, 2021; Revised: 01 August, 2021; Accepted 03 August, 2021 © The author(s) 2021. Published with open access at www.questjournals.org Chronicles of Rajputana: The Valour, Sacrifices and uprightness of Rajputs We are at a fork in the road in India that we have traveled for the past 150 years; and if we are to make true divination of the goal, whether on the right hand or the left, where our searching arrows are winged, nothing could be more useful to us than a close study of the character and history of those who have held supreme power over the country before us, - the waifs.(Sarkar: 1960) Only the Rajputs are discussed in this paper, which is based on Miss Gabrielle Festing's "From the Land of the Princes" and Colonel James Tod's "Annals of Rajasthan." Miss Festing's book does for Rajasthan's impassioned national traditions and dynastic records what Charles Kingsley and the Rev. -

Jahanpanah Part of the Sarai Shahji Village As a Place for Travellers to Stay

CORONATION PARK 3. SARAI SHAHJI MAHAL 5. KHARBUZE KA GUMBAD a walk around The Sarai Shahji Mahal is best approached from the main Geetanjali This is an interesting, yet bizarre little structure, Road that cuts through Malviya Nagar rather than from the Begumpur located within the premises of a Montessori village. The mahal (palace) and many surrounding buildings were school in the residential neighbourhood of Jahanpanah part of the Sarai Shahji village as a place for travellers to stay. Of the Delhi Metro Sadhana Enclave in Malviya Nagar. It is essentially Route 6 two Mughal buildings, the fi rst is a rectangular building with a large a small pavilion structure and gets its name from Civil Ho Ho Bus Route courtyard in the centre that houses several graves. Towards the west, is the tiny dome, carved out of solid stone and Lines a three-bay dalan (colonnaded verandah) with pyramidal roofs, which placed at its very top, that has the appearance of Heritage Route was once a mosque. a half-sliced melon. It is believed that Sheikh The other building is a slightly more elaborate apartment in the Kabir-ud-din Auliya, buried in the Lal form of a tower. The single room is entered through a set of three Gumbad spent his days under this doorways set within a large arch. The noticeable feature here is a dome and the night in the cave located SHAHJAHANABAD Red Fort balcony-like projection over the doorway which is supported by below it. The building has been dated carved red sandstone brackets. -

India Architecture Guide 2017

WHAT Architect WHERE Notes Zone 1: Zanskar Geologically, the Zanskar Range is part of the Tethys Himalaya, an approximately 100-km-wide synclinorium. Buddhism regained its influence Lungnak Valley over Zanskar in the 8th century when Tibet was also converted to this ***** Zanskar Desert ཟངས་དཀར་ religion. Between the 10th and 11th centuries, two Royal Houses were founded in Zanskar, and the monasteries of Karsha and Phugtal were built. Don't miss the Phugtal Monastery in south-east Zanskar. Zone 2: Punjab Built in 1577 as the holiest Gurdwara of Sikhism. The fifth Sikh Guru, Golden Temple Rd, Guru Arjan, designed the Harmandir Sahib (Golden Temple) to be built in Atta Mandi, Katra the centre of this holy tank. The construction of Harmandir Sahib was intended to build a place of worship for men and women from all walks *** Golden Temple Guru Ram Das Ahluwalia, Amritsar, Punjab 143006, India of life and all religions to come and worship God equally. The four entrances (representing the four directions) to get into the Harmandir ਹਰਿਮੰਦਿ ਸਾਰਹਬ Sahib also symbolise the openness of the Sikhs towards all people and religions. Mon-Sun (3-22) Near Qila Built in 2011 as a museum of Sikhism, a monotheistic religion originated Anandgarh Sahib, in the Punjab region. Sikhism emphasizes simran (meditation on the Sri Dasmesh words of the Guru Granth Sahib), that can be expressed musically *** Virasat-e-Khalsa Moshe Safdie Academy Road through kirtan or internally through Nam Japo (repeat God's name) as ਰਿਿਾਸਤ-ਏ-ਖਾਲਸਾ a means to feel God's presence. -

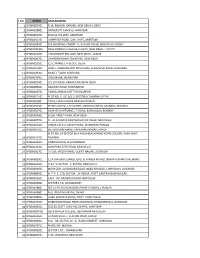

Atms RE CALIBRATED 09.12.2016

S NO ATMID ATM ADDRESS 1 SPSBA007501 E-16, RAJOURI GARDEN, NEW DELHI-110027 2 SPSBA028801 UNIVERSITY,CAMPUS, AMRITSAR 3 SPSBA003101 KHALSA COLLEGE, AMRITSAR 4 SPSBA010201 LAWRENCE ROAD, CIVIL LINES, AMRITSAR 5 SPSBA048701 D-6 SHOPPING CENTRE 11, VASANT VIHAR, NEW DELHI-110057 6 SPSBA090302 DESH BANDHU COLLEGE, KALKAJI, NEW DELHI - 110 019 7 SPSBA061201 7 SIDHARATH ENCLAVE, NEW DELHI -110014 8 SPSBA000701 CHANDNICHOWK FOUNTAIN, NEW DELHI 9 SPSBA056501 C.S.C MARKET, A-BLOCK, DELHI 10 SPSBA015901 SUNET LUDHIANA OPP MILK PLANT,FEROZEPUR ROAD, LUDHIANA 11 SPSBA029301 MODEL TOWN LUDHIANA 12 SPSBA076401 GTB NAGAR, JALANDHAR 13 SPSBA001901 5/1 D.B.ROAD, PAHAR GANJ,NEW DELHI 14 SPSBA000901 RAILWAY ROAD, HOSHIARPUR 15 SPSBA010701 TANDA URMAR DISTT HOSHIARPUR 16 SPSBA072201 PLOT NO: 2, LSC NO: 3, SECTOR-6, DWARKA, DELHI 17 SPSBA053801 195-B, LOHIA NAGAR NEW GHAZIABAD 18 SPSBA052301 FITWEL HOUSE, L B S MARG, VIKHROLI (WEST), MUMBAI, MUMBAI 19 SPSBA064701 MOHAR APARTMENT,L.T.ROAD, BORIVILI(W), BOMBAY 20 SPSBA087801 B-136, PREET VIHAR, NEW DELHI 21 SPSBA087701 D - 31 ACHARYA NIKETAN,MAYUR VIHAR, NEW DELHI 22 SPSBA061301 URBAN ESTATE GARAH ROAD, JALANDHAR PUNJAB 23 SPSBA087101 B55 GAUTAM MARG, HANUMAN NAGAR, JAIPUR PLOT NO. 14 SECTOR 26-A PALM BEACH ROAD KOPRI COLONY, VASHI NAVI 24 SPSBA046701 MUMBAI 25 SPSBA030001 LINKING ROAD, KHAR BOMBAY 26 SPSBA032301 JANGPURA EXTENTION, NEW DELHI 27 SPSBA091701 3 / 536, VIVEK KHAND, GOMTI NAGAR, LUCKNOW 28 SPSBA088301 12 A JAIPURIA SUNRISE GREEN, AHINSA KHAND, INDIRA PURAM GHAZIABAD 29 SPSBA091201 H-32 / 6 SECTOR - 3, ROHINI, NEW DLEHI 30 SPSBA091601 80/19-20/1 GURDWARA ROAD, NAKA HINDOLA, CHAR BAGH, LUCKNOW 31 SPSBA086501 N. -

D:\Journals & Copyright\Notions

Notions Vol. IX, No.2, 2018 ISSN:(P) 0976-5247, (e) 2395-7239 Impact Factor 6.449 (SJIF) UGC Journal No. 42859 A Document on Peace and Protest in the Pages Stained With Blood By Indira Goswami T Vanitha 11/132 Pudhu Nager, Hudco Colony, Tirupur Abstract : Indira Goswamy popularly known as MamoniRaisomGoswami an icon of Assamese Literature presents the contrasting effects of peace as well as protest in her novel pages stained with blood.It was written in Reference to this paper Assamese and later translated by Pradip Acharya in English. should be made as follows: Actually Goswamy desired to write a book on Delhi with its pride and pomp. She settled in a small cooped up flat in T Vanitha, Sather nagar, Delhi. She came across a few Sikh people who helped her in one way or other. She had learnt various anecdotes about the Moghal and the British rulers. Some A Document on Peace were tell- tale stories and some were records of the past. She and Protest in the Pages even visited whores colony to collect sources for her material. Stained With Blood By Where ever she went she showed courtesy to her fellow human Indira Goswami, beings and tried to help them in all possible ways. The novel is an out pour of her bitter memories during the anti -Sikh Notions 2018, Vol. IX, Riots caused by the assassination of Smt. Indira Gandhi No.2, pp. 23-33, when she was the prime minister of India. Neither the Article No. 5 politicians nor the administers bothered much about the communal calamities.