Land Price Diffusion Across Borders the Case of Germany.Pdf —

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

01-04 Titel Innen Und Inhalt.Indd

Vogelmonitoring in Sachsen-Anhalt 2014 Herausgegeben durch das Landesamt für Umweltschutz Sachsen-Anhalt Staatliche Vogelschutzwarte in Zusammenarbeit mit dem Ornithologenverband Sachsen-Anhalt (OSA) e.V. 1 2 Vogelmonitoring in Sachsen-Anhalt 2014 Berichte des Landesamtes für Umweltschutz Sachsen-Anhalt, Halle Heft 5/2015 1. Monitoring seltener Brutvogelarten Stefan Fischer und Gunthard Dornbusch: Bestandssituation ausgewählter Brutvogelarten in Sachsen-Anhalt – Jahresbericht 2014 5 2. Monitoring Greifvögel und Eulen André Staar, Gunthard Dornbusch, Stefan Fischer & Andreas Hochbaum: Entwicklung von Bestand und Reproduktion von Mäusebussard (Buteo buteo), Rotmilan (Milvus milvus) und Schwarzmilan (Milvus migrans) im Naturschutzgebiet Steckby-Lödderitzer Forst / Untersuchungsgebiet Steckby von 1991 bis 2015 43 3. Wasservogel- und Gänsemonitoring Martin Schulze: Die Wasservogelzählung in Sachsen-Anhalt 2014/15 55 4. Bestände Stefan Fischer & Gunthard Dornbusch: Bestand und Bestandsentwicklung der Brutvögel Sachsen-Anhalts – Stand 2010 71 Sven Trautmann, Stefan Fischer & Bettina Gerlach: Ermittlung der Zielwerte nach der Delphi-Methode für den LIKI-Indikator „Artenvielfalt und Landschafts- qualität“ in Sachsen-Anhalt 2015 81 3 4 Bestandssituation ausgewählter Berichte des Landesamtes für Umweltschutz Sachsen-Anhalt Brutvogelarten in Sachsen-Anhalt Halle, Heft 5/2015: 5–41 – Jahresbericht 2014 Stefan Fischer & Gunthard Dornbusch Einleitung Insbesondere bitten wir die Melder bei der Zuord- nung von Beobachtungen zu einzelnen Gebieten Vogeldaten -

Bergbaufolgelandschaft „Harzer Seeland“

® Landmarke 14 Geopunkt 4 Bergbaufolgelandschaft „Harzer Seeland“ HEUTE Wasser überspült sie, Bäume bedecken sie: Die Zeugnisse des einstmals noch heute im Namen. 1828 wurde Braunkohle bei Aschersleben entdeckt. Mio. Jahre größten Tagebaus Mitteldeutschlands liegen heute eher im Verborgenen. Es setzte ein reger Bergbau ein. Der Abbau erfolgte zunächst ausschließ- ) Quartär 2,6 Hier, am Nordufer des Concordia Sees, blicken wir auf eine Landschaft, die lich im Tiefbau, ab 1856 im Tagebau der Grube Concordia Nachterstedt. sich bis heute im Wandel befindet. Der ursprüngliche See entstand durch das Hier kam auch der erste Eimerkettenbagger Deutschlands zum Einsatz. Tie- Tertiär Abschmelzen des Eises der letzten Eiszeit und verlandete später. 1446 ver- fe Einschnitte in die Erdoberfläche (bis 80 m Tiefe) und die Aufschüttung anlasste der Bischof von Halberstadt die Flutung des Sumpfgebietes. Schnell von Hochhalden (bis 20 m Höhe) folgten. Sogar Ortschaften mussten dem Erdneuzeit (Känozoikum 65 siedelten sich Fische und Wasservögel an. Fischerei wurde ein wichtiger Er- Braunkohleabbau weichen: Nachterstedt und Königsaue waren betroffen. werbszweig. Im Ergebnis des Westfälischen Friedens fiel das Fürstbistum Die Menschen wurden dorthin umgesiedelt, wo sich heute die Ortslagen be- Halberstadt 1648 an die Kurfürsten von Brandenburg. Nach fortschreitender finden. 1991 endete die Kohleförderung. Die Flutung des Tagebaurestlochs Kreide erneuter Verlandung ließ FRIEDRICH I. († 1713), König von Preußen, das Gebiet Nachterstedt begann 1996; es entstand der heutige Concordia See. Die mit Anfang des 18. Jh. komplett trocken legen um neues Land für die zunehmen- Bäumen bestandenen Hochhalden werden als Abenteuerspielplatz und Bür- 142 de Bevölkerung zu gewinnen. Friedrichsaue und Königsaue tragen den König gerpark genutzt. Jura Europäische Geoparke Königslutter 28 200 ® Erdmittelalter (Mesozoikum) 20 Oschersleben 27 Trias 18 14 Goslar Halberstadt 3 2 8 1 Quedlinburg 251 4 Osterode a.H. -

Stadt Aschersleben Markt 1 06449 Aschersleben Fon 03473-985-0

LOKALE ENTWICKLUNGS- STRATEGIE DER LEADER-AKTIONSGRUPPE WETTBEWERBSBEITRAG ZUR AUSWAHL VON CLLD / LEADER SUBREGIONEN LOKALE ENTWICKLUNGSSTRATEGIE CLLD/ LEADER I LAG Aschersleben_Seeland I Fassung 19.03.2015 I Seite 1 LOKALE ENTWICKLUNGS- Strategie DER LEADER-AKTIONSGRUPPE Impressum September 2016 Innerhalb der Lokale Entwicklungsstrategie „Aschersleben-Seeland“ wurden 2016 Klarstellung und Ergänzungen vorgenommen. Die Lokale Aktionsgruppe „Aschersleben-Seeland“ beschloss die Anpassungen des Projektbe- wertungsbogens, der Zielnomenklatur, des Handlungsfeldzieles 3 innerhalb des Handlungsfeldes 2 sowie die Ergänzung von Teilzielen und entsprechender Indikatoren. Auftraggeber: LAG Aschersleben-Seeland vertreten durch: Stadt Aschersleben Markt 1 06449 Aschersleben fon 03473-985-0 www.aschersleben.de Ansprechpartner: Herr Schaffhauser fon 03473-958-613 [email protected] Konzeptionelle Redaktion und Begleitung: WENZEL & DREHMANN P_E_M GmbH Jüdenstraße 31 06667 Weißenfels www.wenzel-drehmann.de [email protected] fon 03443-28 43 LOKALE ENTWICKLUNGSSTRATEGIE CLLD/LEADER | LAG Aschersleben-Seeland | Ergänzung vom 19.09.16 | Inhalt 1. Vorbemerkung 5 1.1. Anlass und Ziel der Lokalen Entwicklungsstrategie 5 1.2. Methodik der Erarbeitung der LES 5 1.3. Vorgaben übergeordneter Planung/ aktueller Entwicklungsstrategien 6 2. Gebietsspezifische Analyse 8 2.1. Sozioökonomische Analyse der Region Aschersleben-Seeland 8 2.1.1. Größe, Abgrenzung und Lage des Aktionsgebietes 8 2.1.2. Gebiete mit besonderem Schutzstatus 9 2.1.3. Raum- und Siedlungsstruktur 10 2.1.4. Bevölkerungsbestand und Bevölkerungsentwicklungen 10 2.1.5. Wirtschaftlich Rahmenbedingungen 12 2.1.6. Daseinsvorsorge – soziale Standortfaktoren 14 2.1.7. Entwicklung der Infrastruktur 15 2.1.8. Tourismus – touristische Standortfaktoren 16 2.1.9. Naturraum 17 2.1.10. Identifikationskraft/ Kooperationen/ Netzwerke1 8 2.2. SWOT-Analyse 18 2.2.1. -

Heartland of German History

Travel DesTinaTion saxony-anhalT HEARTLAND OF GERMAN HISTORY The sky paThs MAGICAL MOMENTS OF THE MILLENNIA UNESCo WORLD HERITAGE AS FAR AS THE EYE CAN SEE www.saxony-anhalt-tourism.eu 6 good reasons to visit Saxony-Anhalt! for fans of Romanesque art and Romance for treasure hunters naumburg Cathedral The nebra sky Disk for lateral thinkers for strollers luther sites in lutherstadt Wittenberg Garden kingdom Dessau-Wörlitz for knights of the pedal for lovers of fresh air elbe Cycle route Bode Gorge in the harz mountains The Luisium park in www.saxony-anhalt-tourism.eu the Garden Kingdom Dessau-Wörlitz Heartland of German History 1 contents Saxony-Anhalt concise 6 Fascination Middle Ages: “Romanesque Road” The Nabra Original venues of medieval life Sky Disk 31 A romantic journey with the Harz 7 Pomp and Myth narrow-gauge railway is a must for everyone. Showpieces of the Romanesque Road 10 “Mona Lisa” of Saxony-Anhalt walks “Sky Path” INForMaTive Saxony-Anhalt’s contribution to the history of innovation of mankind holiday destination saxony- anhalt. Find out what’s on 14 Treasures of garden art offer here. On the way to paradise - Garden Dreams Saxony-Anhalt Of course, these aren’t the only interesting towns and destinations in Saxony-Anhalt! It’s worth taking a look 18 Baroque music is Central German at www.saxony-anhalt-tourism.eu. 8 800 years of music history is worth lending an ear to We would be happy to help you with any questions or requests regarding Until the discovery of planning your trip. Just call, fax or the Nebra Sky Disk in 22 On the road in the land of Luther send an e-mail and we will be ready to the south of Saxony- provide any assistance you need. -

Halle - Könnern - 330 Bernburg

Trassenanmeldung Fpl 2022 Aschersleben - Halberstadt - Goslar Halle - Könnern - 330 Bernburg RE4 Halle - Goslar, RE21 Magdeburg - Goslar, RE24 Halle - Halberstadt, RB47 Halle - Bernburg Zug RE RE RE RB RE RB RB RE RB RB RE RE RE 75702 75704 75704 75A38 75748 80412 80532 7570A 80414 8041A 75722 75750 75708 4 4 4 44 21 47 47 4 47 47 24 21 4 von Bernburg Magde- burg Halle (Saale) Hbf. ... = 3.45 ... ... ... C 5.06 B 5.06 5.25 B 6.10 C 6.11 6.39 ... 7.49 Halle Steintorbrücke ... > ... ... ... ; 5.10 ; 5.10 > ;? > > ... > Halle Dessauer Brücke ... > ... ... ... ; 5.12 ; 5.12 > ;? > > ... > Halle Zoo ... > ... ... ... ; 5.14 ; 5.14 > ;? > > ... > Halle Wohnstadt Nord ... > ... ... ... ; 5.16 ; 5.16 > ;? > > ... > o ... ;? ... ... ... ; 5.18 ; 5.18 ? ; 6.17 ; 6.17 6.44 ... ? Halle-Trotha ... ;? ... ... ... ; 5.18 ; 5.18 ? ; 6.18 ; 6.18 6.45 ... ? Teicha ... ;? ... ... ... ; 5.22 ; 5.22 ? ; 6.22 ; 6.22 6.48 ... ? Wallwitz (Saalkreis) ... ;? ... ... ... ; 5.26 ; 5.26 ? ; 6.30 ; 6.30 6.56 ... ? Nauendorf (Saalkreis) ... ;? ... ... ... ; 5.30 ; 5.30 ? ;? ;? 7.00 ... ? Domnitz (Saalkreis) ... ;? ... ... ... ; 5.34 ; 5.34 ? ;? ;? 7.04 ... ? Könnern o ... ; 4.04 ... ... ... ; 5.38 ; 5.38 5.48 ; 6.39 ; 6.39 7.09 ... 8.08 Könnern ... > ... ... ... ; 5.40 ; 5.40 > ; 6.41 ; 6.41 > ... > Baalberge ... > ... ... ... ; 5.59 ; 5.57 > ; 6.58 ; 6.58 > ... > Bernburg-Roschwitz ... > ... ... ... ; 6.03 ; 6.01 > ; 7.02 ; 7.02 > ... > Bernburg Hbf. o ... > ... ... ... C 6.06 B 6.04 > B 7.05 C 7.05 > ... > Könnern ... ; 4.05 ... ... ... ... ... 5.51 ... ... 7.10 ... 8.10 Belleben ... ; 4.12 ... ... ... ... ... 5.59 ... ... 7.18 ... 8.17 o ... ; 4.17 ... ... ... ... ... 6.04 .. -

Angebote Im Bereich Der Frühen Hilfen Im Salzlandkreis Anlage Nach Sozialräumen Und Zielgruppen

Angebote im Bereich der Frühen Hilfen im Salzlandkreis Anlage nach Sozialräumen und Zielgruppen Bereich Aschersleben Zielgruppe Bezeichnung Inhalt Ort der Termin/Dauer Träger Durchführung Schwangere Hebammensprechstunde - Aufklärung zur Geburt Aschersleben Montag, Freitag AMEOS Frauenklinik und Geburtsplanung - Ausfüllen der Aufklä- AMEOS- Frauenklinik zw. 9.00 und 13.00 Aschersleben rungsbögen Uhr - Kreißsaalanmedung ca. 1 ½ Stunden - CTG - bei Bedarf Arztgespräch (Risikopatienten) Schwangere Informationsabende zur - Kreißsaal- und Aschersleben Dauer ca. 2 Stunden AMEOS Frauenklinik Geburt Stationsführung AMEOS- Frauenklinik Aschersleben - Klärung aller anstehenden Fragen zur Schwangerschaft und Geburt Schwangere und Geburtsvorbereitung und Informationen rund um Aschersleben keine festen Termine AMEOS Frauenklinik Wöchnerinnen Wochenbettbetreuung Schwangerschaft, Geburt, AMEOS- Frauenklinik Aschersleben Wochenbett im Rahmen von und/oder Praxisräume In Zusammenarbeit mit Kursen und Einzelberatungen der am Klinikum den freiberuflich tätigen freiberuflich tätigen Hebammen Hebammen: - Dagmar Kaminski (Hecklingen) - Katrin Herrmann (ASL) - Martina Zedler (ASL) - Simone Hille (ASL) Schwangere Frauen Familienhebamme - Anleitung altersgerechte im Haushalt der Eltern unterschiedlich Familienhebamme in besonderen Ernährung, Pflege und Ines Schäfer Lebenssituationen Förderung OT Neundorf 1 Mutter mit Kind von 0 Ascherslebener Str. 3 – 1 Jahr - Beobachtung der 39418 Staßfurt körperlichen und emotionalen Entwicklung des Kindes - Unterstützung , Beratung -

VGS-410 Eisleben-Hettstedt-Aschersleben Gültig Ab: 23.08.2020

VGS-410 Eisleben-Hettstedt-Aschersleben gültig ab: 23.08.2020 Montag-Freitag Fahrtnummer 404 410 412 414 408 416 420 422 426 428 430 432 436 Verkehrbeschränkungen S S Anmerkungen Ankunft aus Sangerhausen 5.20 6.30 7.26 7.26 8.25 9.28 10.25 11.28 12.25 13.28 14.26 Ankunft aus Halle 5.25 6.14 6.14 7.04 7.33 8.31 9.33 10.31 11.33 12.31 13.33 14.31 Eisleben, Bf., Bst. 5 5.38 6.16 6.38 7.31 7.38 8.38 9.38 10.38 11.38 12.58 13.38 14.38 Eisleben, Rathenaustr. 5.39 6.17 6.39 7.32 7.39 8.39 9.39 10.39 11.39 12.59 13.39 14.39 Eisleben, Landwehr 5.41 6.19 6.41 7.34 7.41 8.41 9.41 10.41 11.41 13.01 13.41 14.41 Eisleben, Mansfelder Hof 5.42 6.20 6.42 7.35 7.42 8.42 9.42 10.42 11.42 13.02 13.42 14.42 Eisleben, Plan/Zentrum 5.43 6.21 6.43 7.36 7.43 8.43 9.43 10.43 11.43 13.03 13.43 14.43 Eisleben, Busbf., Bst. 3 5.45 6.23 6.45 7.38 7.45 8.45 9.45 10.45 11.45 13.05 13.45 14.45 Eisleben, Friedhof 5.48 6.25 6.48 7.40 7.48 8.48 9.48 10.48 11.48 13.08 13.48 14.48 Eisleben, Magdeburger Str. -

Laying Down Detailed Rules for Certain Special Cases Regarding the Definition of Sheepmeat and Goatmeat Producers and Producer Groups

7. 8 . 91 Official Journal of the European Communities NO L 219/ 15 COMMISSION REGULATION (EEC) No 2385/91 of 6 August 1991 laying down detailed rules for certain special cases regarding the definition of sheepmeat and goatmeat producers and producer groups THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, declaration signed by all the members and by means of certain provisions on penalties intended to ensure that the group assumes liability for declarations submitted ; Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community, Whereas, for the purposes of applying the abovemen tioned limits, rules should also be laid down for appor tioning livestock in the case of groups where the animals Having regard to Council Regulation (EEC) No 3013/89 belonging to each member cannot be identified ; whereas of 25 September 1989 on the common organization of the formula for apportionment applicable, in the case of the market in sheepmeat and goatmeat ('), as last disbanding, to the group's assets is suitable for the amended by Regulation (EEC) No 1741 /91 (2), and in purpose ; particular Article 5 (9) thereof, Whereas, in order to prevent the limits in question from Having regard to Council Regulation (EEC) No 3493/90 being circumvented, the concept of group should exclude of 27 November 1990 laying down general rules for the any form of association featuring a lack of independence grant of premiums to sheepmeat and goatmeat produc of or real participation by the members ; ers (3), and in particular Articles 1 and 2 (4), Whereas Regulation -

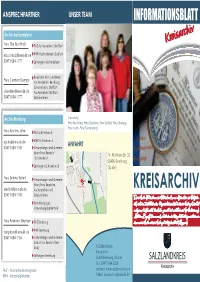

Informationsblatt

ANSPRECHPARTNER UNSER TEAM INFORMATIONSBLATT Archiv Aschersleben Frau Elke Buchholz FAZ Aschersleben, Staßfurt [email protected] KMK Aschersleben,Staßfurt 03471 684-1177 Zeitungen Aschersleben Bauakten der Landkreise Frau Carmen Stumpp Aschersleben, Bernburg, Schönebeck, Staßfurt [email protected] Aschersleben-Staßfurt 03471 684-1177 Salzlandkreis Archiv Bernburg (von links): Frau Buchholz, Frau Stephan, Frau Seifert, Frau Stumpp, Frau Jahn, Frau Fürstenberg. Frau Andrea Jahn FAZ Schönebeck KMK Schönebeck [email protected] ANFAHRT 03471 684-1169 Verwaltungs- und Gemein- B dearchive Bereich a a l berge Th.-Müntzer-Str. 32 Schönebeck 06406 Bernburg r Kre an Zeitungen Schönebeck omas-M n Th - i S s t s (Saale) r T . h tra .-Mü -Peus-S n rich ß in t e e H z e Frau Sabine Seifert r-S Verwaltungs- und Gemein- traße Ba e alb erg r C dearchive Bereiche Kreisarchiv ha u s [email protected] s Aschersleben und e ße e tra 03471 684-1160 Salzlandkreis s t h ac Sammlungsgut, h c Verwaltungsbibliothek S Frau Ramona Stephan FAZ Bernburg [email protected] KMK Bernburg 03471 684-1164 Verwaltungs- und Gemein- dearchive Bereich Bern- burg © Salzlandkreis Kreisarchiv Zeitungen Bernburg 06400 Bernburg (Saale) SALZLANDKREIS Fax: 03471 684-2828 Kreisarchiv FAZ - Facharbeiterzeugnisse Internet: www.salzlandkreis.de KMK - Kreismeldekartei E-Mail: [email protected] Altmarkkreis ÜBER UNS Salzwedel Stendal WERDEN AUCH SIE NUTZER WAS WIR FÜR SIE TUN KÖNNEN IN UNSEREM ARCHIV Börde Bereitstellung von Anschriften geschlosse- Das Kreisarchiv des Salz- Jerichower Land landkreises entstand mit Magdeburg ner Betriebe vor und nach 1990, sowie Salzland tandort Bernburg,g Thomas-Müntzer-Str.32 Unterstützung bei der Suche nach deren Harz S Dessau/ Wittenberg der letzten Verwaltungs- Roßlau Anhalt-Bitterfeld Unterlagen. -

Bekanntmachung Des Kreiswahlleiters Über Die Zugelassenen Wahlvorschläge Und Die Zugelassene Wahlvorschlagsverbindung Für Die Kreistagswahl Am 26

Bekanntmachung des Kreiswahlleiters über die zugelassenen Wahlvorschläge und die zugelassene Wahlvorschlagsverbindung für die Kreistagswahl am 26. Mai 2019 im Salzlandkreis KWL-SLK 03/19 vom 21. März 2019 Gemäß § 28 Absatz 7 Kommunalwahlgesetz des Landes Sachsen-Anhalt (KWG LSA) in Verbindung mit § 36 Absatz 1 Kommunalwahlordnung des Landes Sachsen-Anhalt (KWO LSA) gebe ich hiermit bekannt, dass der Kreiswahlausschuss des Salzlandkreises in seiner Sitzung am 20. März 2019 für die sieben Wahlbereiche im Wahlgebiet jeweils die nachfolgend aufgeführten Wahlvorschläge zugelassen hat. I. Zugelassene Wahlvorschläge für die Kreistagswahl im Salzlandkreis Wahlbereich 1 Wahlvorschlag 1 Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands (CDU) Nachname Vorname Beruf Geburtsjahr Wohnort 1 Dr. Planert Maik Hochschullehrer, Jurist 1974 Aschersleben 2 Schigulski Heike Beamtin im gehobenen Dienst 1973 Aschersleben 3 Dahl Alexandra Studienkreis 1981 Aschersleben 4 Falke Norbert Lehrer 1956 Aschersleben 5 Krause Walter Instandhaltungsmechaniker 1956 Aschersleben OT Winningen 6 Peter Christoph Lehrer an Sekundarschulen 1987 Aschersleben 7 Schmith Andreas Diplomhistoriker 1961 Aschersleben 8 Schulze Ernst- Sparkassendirektor a. D. 1954 Aschersleben Joachim 9 Schwemmer Martin Kaufmann 1966 Aschersleben Wahlvorschlag 2 Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) Nachname Vorname Beruf Geburtsjahr Wohnort 1 Rausch Daniel CNC-Programmierer 1963 Staßfurt OT Glöthe 2 Krebs Michael Strafvollzugsbeamter im 1973 Aschersleben Ruhestand Wahlvorschlag 3 DIE LINKE. (LINKE.) Nachname -

Sachsen/Sachsen-Anhalt/Thüringen Resources at the IGS Library

Sachsen/Sachsen-Anhalt/Thüringen Resources at the IGS Library Online (General) Ahnenforschung.org “Regional Research” — http://forum.genealogy.net Middle Germany Genealogical Assoc. (German) — http://www.amf-verein.de Gazeteer to Maps of the DDR — https://archive.org/details/gazetteertoams1200unit Mailing Lists (for all German regions, plus German-speaking areas in Europe) — http://list.genealogy.net/mm/listinfo/ Periodicals (General) Mitteldeutsche Familienkunde: Band I-IV, Jahrgang 1.-16. 1960-1975 bound vols. Band V-VII, Jahrgang 17.-24. 1976-1983 complete Band VII, Jahrgang 25. 1984, Hefte 1, 3, 4. Band VIII, Jahrgang 26.-28. 1985-1987 complete Library Finding Aids (General) list of Middle German Ortsfamilienbücher from the AMF e.V. website — note: see the searchable file in the “Saxony Finding Aids” folder on computer #1’s desktop. SACHSEN (SAC) Online FamilySearch Wiki page on Saxony — http://tinyurl.com/odcttbx Genwiki Sachsen page — http://wiki-de.genealogy.net/Sachsen Saxony & Saxony Roots ML’s — http://www.germanyroots.com/start.php?lan=en Leipzig Genealogical Society — http://www.lgg-leipzig.de Saxony research links (German) — http://wiki-de.genealogy.net/Sachsen/Linkliste Archive of Saxony — http://www.archiv.sachsen.de German Genealogy Central Office (German) — http://www.archiv.sachsen.de/6319.htm Digital Historical Place Index (German) — http://hov.isgv.de Private Dresden research page — http://www.ahnenforschung-hanke.de/index.php Private Chemnitz area research page — http://stammbaum.bernhard-schulze.de City books of Dresden -

Halle (Saale) Goslar – Halberstadt – Aschersleben Bernburg

330 Jan. Dez. oder Nov. Halle (S.) Halle Okt. Starker Nahverkehr Nahverkehr Starker Sachsen-Anhalt in www.insa.de Tel. 0391 5363180 0391 Tel. RB 44 Sep. Jeder Mensch hat Ziele. Wir bringen Sie hin. Könnern Aug. 24 HBX RE Jul. Jun. 21 oder RE RB 50 Mai in Sachsen-Anhalt in 0800 ABELLIO 0800 223 5546 (kostenfrei; 24h erreichbar) 01803 000 111 4 Aschersleben Apr. [email protected] Abellio Rail Mitteldeutschland GmbH Postfach 1116 04417 Markranstädt Kundenservice Starker Nahverkehr in Sachsen-Anhalt www.insa.de oder Tel. 0391 5363180 RE Tel. 0391 5363180 0391 Tel. Starker Starker Nahverkehr in Sachsen- Anhalt Nahverkehr Starker Sachsen-Anhalt in www.insa.de RB 47 Bernburg Mrz. gültig: 15.12.2019 - 12.12.2020 Halberstadt Feb. Hotline: Fax: E-Mail: Serviceadresse: www.abellio.de Starker Nahverkehr Starker Mit Unterstützung von: Goslar Herausgeber: Abellio Rail Mitteldeutschland GmbH, Magdeburger Straße 51, 06112 Halle Jan. Bernburg/Goslar – Halle (Saale) @ Wo erfahren Sie alles zu Wo Fahrplanabweichungen und Störungen? Wir informieren Sie im Internet unter www.abellio.de/mitteldeutschland über die aktuelle Verkehrslage und über Störungen. Bei kurzfristigen Störungen achten Sie auch auf die Ansagen unserer Kundenbetreuer in den Zügen oder auf die Informationen an den Bahnsteigen. Dez. Sie haben noch Fragen Sie haben noch Fragen oder Anregungen? 1 2 3 Kursbuch der Deutschen Bahn 2020 Bernburg www.bahn.de/kursbuch Könnern – Halle (Saale) Aschersleben - Halberstadt - Goslar Goslar – Halberstadt330 Halle - Könnern– Aschersleben o