Understanding Enigmatic Life of Solitude of Goan Devadasis Through Dekhni Songs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3 World Literature in a Poem the Case of Herberto Helder1

3 World Literature in a Poem The Case of Herberto Helder1 Helena C. Buescu It is arguable that, if world literature is also a mode of reading, as David Damrosch states, there may be special cases in which the choice of works to be read and/or to be translated has to be accounted for as a poetic gesture towards a planetary literary awareness. In such instances, the sense of literary estrangement is part of the reading process, and the project of its non- domestication (perhaps a stronger way to draw on Lawrence Venuti’s notion of foreignization) is very much at the centre of the hermeneutical process. In what follows I will be dealing with an interesting case of translation (or some- thing akin to it), from the point of view of a poet. It is not only that it is a poet who translates poems by others. It is also, as we shall see, that he translates them as a poet, that is, as part of his own poetic stance. What is (and what isn’t) a literary translation? That is the question that lies at the heart of this endeavour. As we shall see, it is also a case in which, through translation, cultural diversity and provenance are transformed into a clearly distinguished work: translating is a mode of reading, but it is also a mode of shifting socio- logical and aesthetic functions and procedures. This is why we may be able to say that world literature is not solely a mode of reading, but a mode that deals with the constant invention of reading—by reshaping the centre and the peripheries of literary systems, and by thus proposing ever-changing forms of actually reading texts that seemed to have been already read. -

A Commercial Study of TIATR As a Form of Entertainment in Goa (India

A Commercial Study of TIATR as a form of Entertainment in Goa (India): An Empirical Analysis Dr.Juao Costa Associate Professor, Rosary College of Commerce and Arts, Navelim, Salcete, Goa. 403707. Abstract: Introduction: The state of Goa is rich in culture; heritage and art The state of Goa is rich in culture; heritage and art especially performing art in Goa is a unique feature of especially performing art in Goa is a unique feature of the state. Though all these forms fall under the wide the state. Though all these forms fall under the wide classification of dance, dramas and music yet the classification of dance, dramas and music yet the dance in Goa has a distinct Goan flavour and can be dance in Goa has a distinct Goan flavour and can be easily be distinguished from those of the other states. easily be distinguished from those of the other states. The most significant part about the performing arts in The most significant part about the performing arts in Goa is the fact that each of them colorfully illustrates Goa is the fact that each of them colourfully illustrates the unity in diversity of Goan heritage. Goan rich the unity in diversity of Goan heritage. Goan rich cultural heritage comprises of dance, folksongs, music cultural heritage comprises of dance, folksongs, music and folk tales rich in the content and variety. Goans are and folk tales rich in the content and variety. Goans are born music lovers. Goans are very fond of theatre and born music lovers. Goans are very fond of theatre and acting. -

Jennings on the Trail of Pessoa Or Dimensions of Poetical Music

Jennings on the Trail of Pessoa or dimensions of poetical music Pedro Marques* Keywords Fernando Pessoa, Hubert Jennings, Roy Campbell, Peter Rickart, translation, versification, musicality, The thing that hurts and wrings, What grieves me is not, What saddens me is not. Abstract Here we present two unpublished essays by Hubert Jennings about the challenges of translating the poetry of Fernando Pessoa: the first one of them, brief and fragmentary, is analyzed in the introduction; the second, longer and also covering issues besides translation, is presented in the postscript. Having as a starting point the Pessoan poem “O que me doe” and three translations compared by Hubert Jennings, this presentation examines some aspects of poetic musicality in the Portuguese language: verse measurement, stress dynamics, rhymes, anaphors, and parallelisms. The introduction also discusses how much the English versions of the poem, which are presented by Jennings, recreate (or not) the musical-poetic dimensions of the original text. Palavras-chave Fernando Pessoa, Hubert Jennings, Roy Campbell, Peter Rickart, tradução, versificação, musicalidade, O que me doe, O que me dói. Resumo Reproduzem-se aqui dois ensaios inéditos de Hubert Jennings sobre os desafios de se traduzir a poesia de Fernando Pessoa: o primeiro deles, breve e fragmentário, é analisado numa introdução; o segundo, mais longo e versando também sobre questões alheias à tradução, é apresentado em postscriptum. A partir do poema pessoano “O que me dói” e de três traduções comparadas por Hubert Jennings, esta apresentação enfoca alguns aspectos da música poética em língua portuguesa: medida do verso, dinâmica dos acentos, rimas, anáforas e paralelismos. -

Folk Theatre in Goa: a Critical Study of Select Forms Thesis

FOLK THEATRE IN GOA: A CRITICAL STUDY OF SELECT FORMS THESIS Submitted to GOA UNIVERSITY For the Award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Ms. Tanvi Shridhar Kamat Bambolkar Under the Guidance of Dr. (Mrs.) K. J. Budkuley Professor of English (Retd.), Goa University. January 2018 CERTIFICATE As required under the University Ordinance, OA-19.8 (viii), I hereby certify that the thesis entitled, Folk Theatre in Goa: A Critical Study of Select Forms, submitted by Ms. Tanvi Shridhar Kamat Bambolkar for the Award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English has been completed under my guidance. The thesis is the record of the research work conducted by the candidate during the period of her study and has not previously formed the basis for the award of any Degree, Diploma, Associateship, Fellowship or other similar titles to her by this or any other University. Dr. (Mrs.) K.J.Budkuley Professor of English (Retd.), Goa University. Date: i DECLARATION As required under the University Ordinance OA-19.8 (v), I hereby declare that the thesis entitled, Folk Theatre in Goa: A Critical Study of Select Forms, is the outcome of my own research undertaken under the guidance of Dr. (Mrs.) K.J.Budkuley, Professor of English (Retd.),Goa University. All the sources used in the course of this work have been duly acknowledged in the thesis. This work has not previously formed the basis of any award of Degree, Diploma, Associateship, Fellowship or other similar titles to me, by this or any other University. Ms. -

Browl\ CO-DIRECTORESIEDITORS Onesimo Teot6nio Almeida, Brown University George Monteiro, Brown University

,. GAVEA -BROWl\ CO-DIRECTORESIEDITORS Onesimo Teot6nio Almeida, Brown University George Monteiro, Brown University EDITOR EXECUTIVOIMANAGING EDITOR Alice R. Clemente, Brown University CONSELHO CONSULTIVOIADVISORY BOARD Francisco Cota Fagundes, Univ. Mass., Amherst Manuel da Costa Fontes, Kent State University Jose Martins Garcia, Universidade dos Afores Gerald Moser, Penn. State University Mario J. B. Raposo, Universidade de Lisboa Leonor Simas-Almeida, Brown University Nelson H. Vieira, Brown University Frederick Williams, Univ. Callf., Santa Barbara Gdvea-Brown is published annually by Gavea-Brown Publications, sponsored by the Department of Portuguese and Brazilian Studies, Brown University. Manuscripts on Portuguese-American letters and/or studies are welcome, as well as original creative writing. All submissions should be accompanied by a self-addressed stamped envelope to: Editor, Gdvea-Brown Department of Portuguese and Brazilian Studies Box 0, Brown University Providence, RI. 02912 Cover by Rogerio Silva ~ GAVEA-BROWl' Revista Bilingue de Letras e Estudos Luso-Americanos A Bilingual Journal ofPortuguese-American Letters and Studies VoIs. XVII-XVIII Jan.1996-Dec.1997 SUMARIo/CONTENTS ArtigoslEssays THE MAINSTREAMING OF PORTUGUESE CULTURE: A SYMPOSIUM Persons, Poems, and Other Things Portuguese in American Literature ........................................................ 03 George Monteiro Cinematic Portrayals of Portuguese- Americans ....................................................................... 25 Geoffrey L. Gomes -

Goa University Glimpses of the 22Nd Annual Convocation 24-11-2009

XXVTH ANNUAL REPORT 2009-2010 asaicT ioo%-io%o GOA UNIVERSITY GLIMPSES OF THE 22ND ANNUAL CONVOCATION 24-11-2009 Smt. Pratibha Devisingh Patil, Hon ble President of India, arrives at Hon'ble President of India, with Dr. S. S. Sidhu, Governor of Goa the Convocation venue. & Chancellor, Goa University, Shri D. V. Kamat, Chief Minister of Goa, and members of the Executive Council of Goa University. Smt. Pratibha Devisingh Patil, Hon'ble President of India, A section of the audience. addresses the Convocation. GOA UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT 2009-10 XXV ANNUAL REPORT June 2009- May 2010 GOA UNIVERSITY TALEIGAO PLATEAU GOA 403 206 GOA UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT 2009-10 GOA UNIVERSITY CHANCELLOR H. E. Dr. S. S. Sidhu VICE-CHANCELLOR Prof. Dileep N. Deobagkar REGISTRAR Dr. M. M. Sangodkar GOA UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT 2009-10 CONTENTS Pg, No. Pg. No. PREFACE 4 PART 3; ACHIEVEMENTS OF UNIVERSITY FACULTY INTRODUCTION 5 A: Seminars Organised 58 PART 1: UNIVERSITY AUTHORITIES AND BODIES B: Papers Presented 61 1.1 Members of Executive Council 6 C; ' Research Publications 72 D: Articles in Books 78 1.2 Members of University Court 6 E: Book Reviews 80 1.3 Members of Academic Council 8 F: Books/Monographs Published 80 1.4 Members of Planning Board 9 G. Sponsored Consultancy 81 1.5 Members of Finance Committee 9 Ph.D. Awardees 82 1.6 Deans of Faculties 10 List of the Rankers (PG) 84 1.7 Officers of the University 10 PART 4: GENERAL ADMINISTRATION 1.8 Other Bodies/Associations and their 11 Composition General Information 85 Computerisation of University Functions 85 Part 2: UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENTS/ Conduct of Examinations 85 CENTRES / PROGRAMMES Library 85 2.1 Faculty of Languages & Literature 13 Sports 87 2.2 Faculty of Social Sciences 24 Directorate of Students’ Welfare & 88 2.3 Faculty of Natural Sciences 31 Cultural Affairs 2.4 Faculty of Life Sciences & Environment 39 U.G.C. -

Goa Government Of

IReg. No. GR/RNP/GOAl3ZI I RNINo.GOAENG/2002/6410 I Panaji. 27th January, 2005 (Magha 7, 1926) SERIES III N~ .. 44 OFFICIAL GAZETTE r GOVERNMENT OF GOA GOVERNMENT OF GOA Registration of Tourist Trade Act, 1982, is. hereby • cancelled as the said Tourist Taxi -has been converted Department of Tourism into a private vehicle with effect from 20-12-2002, Directorate of Tourism bearing No. GA-Ol/R-3879. Panaji, 7th December, 2004.- The Director of Order Tourism & Prescribed Authority, A. C. Pereira. No. 5/S(4-694)/2004-DT/2124 The Registration of Tourist· Thxi No. GA-02/V-2123 Or.der belonging to Shri Filipe Pereira, H. No. 286, Benaulim, No. 5/S(4-1501)/2004'DT/2158 Salcete Goa, ':'nder the Goa Registration of Tourist Trade Act, 1982, entered in register NO ... 15 at page The Registration of Tourist Thxi No. GA-02/U-3237 No.5 is hereby cancelled as the said Tourist Thxi has belonging to Shri Anthony M. Fernandes, H. No. 516, been conyerted into a ·private vehicle with effect from Curilo, Majorda, Salcete Goa, under the Goa 28-06-2004, bearing No. GA-08/A-2707. Registration of Tourist Trade Act, 1982, entered in register No. 21 at page No. 87 is hereby cancelled as Panaji, 7th December, 2004.-,. The Director. of the said Tourist Taxi has' been converted into a Tourism & Prescribed'Authority, A. C. Pereira. private vehicle with effect from 10-07-2004, bearing No. GA-Ol/C-7877. Panaji, 7th December, 2004.- The Director of Order Tourism & Prescribed Authority, A. -

Directorate of Planning Statistics and Evaluation

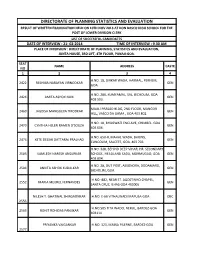

DIRECTORATE OF PLANNING STATISTICS AND EVALUATION RESULT OF WRITTEN EXAMINATION HELD ON 10TH NOV 2013 AT DON BASCO HIGH SCHOOL FOR THE POST OF LOWER DIVISION CLERK LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES DATE OF INTERVIEW : 21- 02-2014 TIME OF INTERVIEW : 9.30 AM PLACE OF INTERVIEW : DIRECTORATE OF PLANNING, STATISTICS AND EVALUATION, JUNTA HOUSE, 3RD LIFT, 4TH FLOOR, PANAJI-GOA. SEAT NAME ADDRESS CASTE NO 1 2 3 4 H.NO. 18, GIRKAR WADA, HARMAL, PERNEM, 2422 RESHMA NARAYAN VIRNODKAR GEN GOA. H.NO. 286, KUMYAMAL, SAL, BICHOLIM, GOA 2424 AMITA ASHOK NAIK GEN 403 503. MAULI PRASAD BLDG, 2ND FLOOR, MANGOR 2460 JAGDISH MANGUEXA TIRODKAR GEN HILL, VASCO DA GAMA , GOA 403 802. H.NO. 18, BHAGWATI ENCLAVE, CHIMBEL, GOA 2470 CYNTHIA HELEN RAMEN D'SOUZA GEN 403 006. H.NO. 650-II, MAHAL WADA, BHIUNS, 2474 XETE DESSAI DATTARAJ PRALHAD GEN CUNCOLIM, SALCETE, GOA. 403 703. H.NO. 328, BEHIND DEEP VIHAR, HR. SECONDARY 2503 KAMLESH NARESH ANSURKAR SCHOOL, HEADLAND SADA, MORMUGAO, GOA GEN 403 804. H.NO. 28, OUT POST, ASSONORA, DODAMARG, 2504 ANKITA ASHOK KUDALKAR GEN BICHOLIM, GOA. H.NO.-882, NEAR ST. AGOSTINHO CHAPEL, 2552 MARIA MEUREL FERNANDES GEN SANTA CRUZ, ILHAS-GOA 403005 NILESH T. GHATWAL SHIRGAONKAR H.NO. E-66 VITHALWADI MAPUSA-GOA OBC 2556 H.NO.505 TITA WADO, NERUL, BARDEZ-GOA 2563 ROHIT ROHIDAS PANJIKAR GEN 403114 PRIYANKA VAIGANKAR H.NO. 323, MAINA PILERNE, BARDEZ-GOA GEN 2577 H.NO. 85/A, MASTIMOL, CANACONA GOA 2587 RINA M. KIRLOSKAR GEN 403702 2589 RAJESH A. PRABHU DESAI H.NO. 508, MALVEMOL-COLA, CANACONA- GOA GEN JAIRAM COMPLEX, A-1 BLDG. -

General Body Minutes 28-06-2018

MINUTES OF THE GENERAL BODY MEETING OF THE BOARD CONVENED ON 28/06/2018 AT 10.00 A.M. IN THE CONFERENCE HALL OF THE DIRECTORATE OF EDUCATION, PORVORIM- GOA The following Members attended the meeting:- 1. Shri. Ramkrishna Samant – Chairman 15. Shri. Hemant Madhusudan Kamat 2. Dr. Uday Gaunkar- Vice Chairman 16. Shri. Conrad C. Mendes 3. Director of Skill Development & 17. Shri. Shashikant K. Punaji Entrepreneurship 18. Shri. Pandurang J. Prabhudessai 4. Director, State Council of Educational 19. Shri. Sanjay Naik Research & Training. 20. Shri. Oscar A. A. Da Costa 5. Dr. Satish Hari Prabhu Keluskar 21. Shri. Mahesh Pandhari Bhagat 6. Prof. Vrushali Mandrekar 22. Smt. Miriam Ann Duarte 7. Dr. Nandkumar M. Kamat 23. Shri. Gopal Prabhu 8. Shri. Ramdas V. Kelkar 24. Shri. Parshuram N Gawade 9. Shri. Walter A. S. Cabral 25. Shri. Devanand S. Satarkar 10. Dr. Celsa Pinto 26. Shri. Dilesh Gadekar 11. Shri. Damodar Guna Phadte 27. Smt. Maria B. D. A. Pereira 12. Shri. Sudan Fati Naik Gaonkar 28. Shri. Nagendra D. Kore 13. Smt. Maria Gorette Alphonso Shri. Bhagirath G. Shetye - 14. Shri. Joseph J. V. R. Coutinho Secretary Leave of absence was granted to following Members as per their request:- 1. Hon. MLA Shri. Nilesh Cabral 2. Director of School Education 3. Dr. Allan Abreo Joseph 4. Dr. Sadanand Hinde 5. Shri. Mahesh Vengurlekar The following members did not attend the meeting:- 1. Hon. MLA. Shri. Dayanand Sopte 2. Director of Higher Education 3. Director of Technical Education 4. Director of Sports & Youth Affairs 5. Director of Art and Culture 6. -

The Case of Goa, India

109 ■ Article ■ The Formation of Local Public Spheres in a Multilingual Society: The Case of Goa, India ● Kyoko Matsukawa 1. Introduction It was Jurgen Habermas, in his Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere [1991(1989)], who drew our attention to the relationship between the media and the public sphere. Habermas argued that the public sphere originated from the rational- critical discourse among the reading public of newspapers in the eighteenth century. He further claimed that the expansion of powerful mass media in the nineteenth cen- tury transformed citizens into passive consumers of manipulated public opinions and this situation continues today [Calhoun 1993; Hanada 1996]. Habermas's description of historical changes in the public sphere summarized above is based on his analysis of Europe and seems to come from an assumption that the mass media developed linearly into the present form. However, when this propo- sition is applied to a multicultural and multilingual society like India, diverse forms of media and their distribution among people should be taken into consideration. In other words, the media assumed their own course of historical evolution not only at the national level, but also at the local level. This perspective of focusing on the "lo- cal" should be introduced to the analysis of the public sphere (or rather "public spheres") in India. In doing so, the question of the power of language and its relation to culture comes to the fore. 松 川 恭 子Kyoko Matsukawa, Faculty of Sociology, Nara University. Subject: Cultural Anthropology. Articles: "Konkani and 'Goan Identity' in Post-colonial Goa, India", in Journal of the Japa- nese Association for South Asian Studies 14 (2002), pp.121-144. -

Identitarian Spaces of the Goan Diasporic Communities

Identitarian Spaces of the Goan Diasporic Communities Thesis Submitted to Goa University For the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In English by Ms. Leanora Madeira née Pereira Under the Guidance of Prof. Nina Caldeira Department of English Goa University, Taleigao Plateau, Goa. India-403206 August, 2020 CERTIFICATE I hereby certify that the thesis entitled “Identitarian Spaces of Goan Diasporic Communities” submitted by Ms. Leanora Pereira for the award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English, has been completed under my supervision. The thesis is a record of the research work conducted by the candidate during the period of her study and has not previously formed the basis for the award of any degree, diploma or certificate of this or any other University. Prof. Nina Caldeira, Department of English, Goa University. ii Declaration As required under the Ordinance OB 9A.9(v), I hereby declare that this thesis titled Identitarian Spaces of the Goan Diasporic Communities is the outcome of my own research undertaken under the guidance of Professor Dr. Nina Caldeira, Department of English, Goa University. All the sources used in the course of this work have been duly acknowledged in this thesis. This work has not previously formed the basis of any award of Degree, Diploma, Associateship, Fellowship or any other titles awarded to me by this or any other university. Ms. Leanora Pereira Madeira Research Student Department of English Goa University, Taleigao Plateau, Goa. India-403206 Date: August 2020 iii Acknowledgement The path God creates for each one of us is unique. I bow my head to the Almighty acknowledging him as the Alpha and the Omega and Lord of the Universe. -

District Census Handbook, North Goa

CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 SERIES 6 GOA DISTRICT CENSUS HAND BOOK PART XII-A AND XII-B VILLAGE AND TOWN DIRECTORY AND VILLAGE AND TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT NORTH GOA DISTRICT S. RAJENDRAN DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS, GOA 1991 CENSUS PUBLICATIONS OF GOA ( All the Census Publications of this State will bear Series No.6) Central Government Publications Part Administration Report. Part I-A Administration Report-Enumeration. (For Official use only). Part I-B Administration Report-Tabulation. Part II General Population Tables Part II-A General Population Tables-A- Series. Part II-B Primary Census Abstract. Part III General Economic Tables Part III-A B-Series tables '(B-1 to B-5, B-l0, B-II, B-13 to B -18 and B-20) Part III-B B-Series tables (B-2, B-3, B-6 to B-9, B-12 to B·24) Part IV Social and Cultural Tables Part IV-A C-Series tables (Tables C-'l to C--6, C-8) Part IV -B C.-Series tables (Table C-7, C-9, C-lO) Part V Migration Tables Part V-A D-Series tables (Tables D-l to D-ll, D-13, D-15 to D- 17) Part V-B D- Series tables (D - 12, D - 14) Part VI Fertility Tables F-Series tables (F-l to F-18) Part VII Tables on Houses and Household Amenities H-Series tables (H-I to H-6) Part VIII Special Tables on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled SC and ST series tables Tribes (SC-I to SC -14, ST -I to ST - 17) Part IX Town Directory, Survey report on towns and Vil Part IX-A Town Directory lages Part IX-B Survey Report on selected towns Part IX-C Survey Report on selected villages Part X Ethnographic notes and special studies on Sched uled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Part XI Census Atlas Publications of the Government of Goa Part XII District Census Handbook- one volume for each Part XII-A Village and Town Directory district Part XII-B Village and Town-wise Primary Census Abstract GOA A ADMINISTRATIVE DIVISIONS' 1991 ~.