¡Vamonos Pa'l Chuco!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entertainmentpage 19 Technique • Friday, October 19, 2007 • 19

ENTERTAINMENTpage 19 Technique • Friday, October 19, 2007 • 19 FLOUNDERING VOLLEY TECH HOSTS MODEL UN Tech’s women’s volleyball team lost Students from Southeastern high ENTERTAINMENT Tuesday to undefeated Clemson. Th eir schools came to attend the 9th annual Page 33 Page 11 Technique • Friday, October 19, 2007 record has dropped to 5-4. Model UN Conference. Fall gets cool with fun festivals Food festival serves it up Atlanta unmasks Echo By Hahnming Lee By Hahnming Lee & Jarrett Oakley Sports Editor Sports Editor/Contributing Writer Taste of Atlanta attracted thousands to sample some of Atlanta’s Th is past weekend saw the inaugural run of a new music festival best food this past weekend at Atlantic Station. Starting Oct. 13, based in Atlanta: the Echo Project, which aimed to inform and this special two-day event hosted several of the most popular promote ecologically friendly advice and knowledge about the and acclaimed restaurants in the area, giving them a chance human footprint that’s destroying the environment. to show off their food to the public. Stands were Some 15,000 green-conscious patrons showed set up on the sidewalks of Atlantic Station, with up to see 80-plus bands on this fi rst of at least 10 chefs and waiters preparing signature dishes for annual music festival extravaganzas Oct. 12-14, people roaming the street. set on the beautiful 350-plus acres of Bouckaert Customers purchased entrance tickets and food Farm just 20 minutes south of Atlanta. coupons for the event that could be spent at vari- Along with a myriad of sponsors and vendors ous stands at their discretion. -

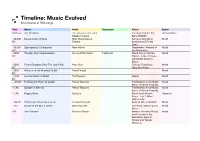

Timeline: Music Evolved the Universe in 500 Songs

Timeline: Music Evolved the universe in 500 songs Year Name Artist Composer Album Genre 13.8 bya The Big Bang The Universe feat. John The Sound of the Big Unclassifiable Gleason Cramer Bang (WMAP) ~40,000 Nyangumarta Singing Male Nyangumarta Songs of Aboriginal World BC Singers Australia and Torres Strait ~40,000 Spontaneous Combustion Mark Atkins Dreamtime - Masters of World BC` the Didgeridoo ~5000 Thunder Drum Improvisation Drums of the World Traditional World Drums: African, World BC Samba, Taiko, Chinese and Middle Eastern Music ~5000 Pearls Dropping Onto The Jade Plate Anna Guo Chinese Traditional World BC Yang-Qin Music ~2800 HAt-a m rw nw tA sxmxt-ib aAt Peter Pringle World BC ~1400 Hurrian Hymn to Nikkal Tim Rayborn Qadim World BC ~128 BC First Delphic Hymn to Apollo Petros Tabouris The Hellenic Art of Music: World Music of Greek Antiquity ~0 AD Epitaph of Seikilos Petros Tabouris The Hellenic Art of Music: World Music of Greek Antiquity ~0 AD Magna Mater Synaulia Music from Ancient Classical Rome - Vol. 1 Wind Instruments ~ 30 AD Chahargan: Daramad-e Avval Arshad Tahmasbi Radif of Mirza Abdollah World ~??? Music for the Buma Dance Baka Pygmies Cameroon: Baka Pygmy World Music 100 The Overseer Solomon Siboni Ballads, Wedding Songs, World and Piyyutim of the Sephardic Jews of Tetuan and Tangier, Morocco Timeline: Music Evolved 2 500 AD Deep Singing Monk With Singing Bowl, Buddhist Monks of Maitri Spiritual Music of Tibet World Cymbals and Ganta Vihar Monastery ~500 AD Marilli (Yeji) Ghanian Traditional Ghana Ancient World Singers -

Still Runnin' with the Devil

Music.Gear.Style. No.74 October 2015 Van Halen Live Still Runnin’ With the Devil NEW ALBUMS from the Dead Weather, Kurt Vile, Patty Griffin, Metric, the Weeknd, Iron Maiden, Slayer, Protomartyr, Mike Reed, and More THE GENIUS OF THE LATEST MILES DAVIS ARCHIVAL COLLECTION FOO FIGHTERS AND CHEAP TRICK ROCK WRIGLEY FIELD GERMAN EXCELLENCE: AMG’s Giro Turntable AMERICAN STYLE: Fern & Roby’s Compact Integrated Amp LONG-TERM LOVE: Rega’s Aria Phono BRITISH BRILLIANCE: The ProAc Tablette Anniversary Fun Toys from Apple, IKEA, and More! WCT_TONE_Dec2014.indd 1 6/10/15 3:31 PM Listen to Your Speakers In A New Way Don’t let your existing wired loudspeakers miss out on high-resolution streaming audio. Paradigm’s new PW AMP delivers 200-Watts of Ultra Class-D power and lets you wirelessly stream high-resolution audio to existing loudspeakers over your home Wi-Fi network. Set-up is simple, app control is easy, and your options are unlimited. Go wireless, with Paradigm-level performance. Exclusive Anthem Room Correction (ARC™) technology uses a digital microphone with advanced DSP algorithms to correct for room distortions in any space. You’ll actually hear the difference ARC makes. ™ PW600 Wireless Freedom. Paradigm Performance. PW800™ A Better Audio Experience. PWLINK ™ PWAMP™ Stream music to any Paradigm Premium Wireless Series product using your Android, PC or iOS device. Only Paradigm delivers wireless performance that is truly on par with traditional non-streaming audio systems. ARC ™ Digital Microphone Room Correction Technology Visit paradigm.com for more info. tone style Meteor M2 Powered 87 Speakers Vintage Look, Portable Sound 11. -

TCU Daily Skiff Creases

SPORTS OPINION Junior linebacker Josh Goolcby has had In America lies under siege from within as the Bush administra- battle injuries to get on the field. Page 10 tion increases the restraints on civil liberties. Page 3 FEATURE Gallery staying 'Afloat' TCU DAILYh SKIFF Art in the Metroplex exhibits 36 juried works JL ^**^ ^^ In its 10()' year of service to Texas Christian Universityty chosen from over 500 entries from local artists at the University Gallery. Page 5 Vol. KM) • [»» je 9 • Fort Worth. Texas wu w.skiff.tcu.edu Thursday, September 12. 2002 Endowment down because of economic factors Two chairwomen set history, have TCU's endowment has shrunk has cut away about 15 percent of tuition and fees, interest off en- 15 percent since March 2000. TCU's endowment since March dowments and gifts from private Endowment Values (fiscal year end) donors. She said the university work to be done Since interest off the endow- 2000 and left the administration 1000 without many options for new in- can also ask departments to real- ment supplies a quarter of the „ 900 This is the first year the Faculty Senate and come. locate money. university's operating budget, S 800 Staff Assembly have been chaired by women the squeeze may pressure the Carol "Right now we are sensitive to moving it at the same time. from one pro % 700^ university to increase tuition and Campbell, the fad that families ore Joe- vice chan- gram to fund reallocate money from one aca- ing the same (financial) cellor of another. m S00 ■•"' BY AMY JOHNSON demic department to another. -

Vodafone Paredes De Coura 2017

DOSSIER DE IMPRENSA VODAFONE PAREDES DE COURA 2017 Vodafone Paredes de Coura Ritmos Edição 2017 Biblioteca Digital Vodafone Vozes da Escrita Vodafone Music Sessions Acções Vodafone Vodafone FM Fest Cool Down Palco Jazz Relva Sobe à Vila Cartaz 2017 Programação por Dias Biografias Contactos 2017 © RITMOS, LDA VODAFONE PAREDES DE COURA 2017 VODAFONE O Vodafone Paredes de Coura está de regresso às margens do Taboão para celebrar a 25.ª edição. paredes DE São 25 anos de história repletos de momentos inesquecíveis. Das atuações COURA memoráveis, ao reencontro entre amigos e ao convívio com a natureza, o festival cresceu e deu fama internacional à vila minhota, que é agora destino de férias de eleição para tantos que a visitam. O Vodafone Paredes de Coura, habitat natural da música, mudou a forma de a ouvir, e viver. Soube despertar tendências, arriscar sonoridades, descobrir novos talentos, consagrar grandes nomes. Uma caminhada de esforços e superações, de provas e de conquistas, de lutas e de vitórias. 25 anos depois, a música continua no centro das atenções de um festival de experiências únicas. A história da música em Portugal não seria a mesma sem o Festival Paredes de Coura. EDIÇÃO 2016 A 24.ª edição materializou o sonho sob a forma de quatro dias de música em comunhão com a natureza, numa celebração conjunta que levou perto de 100 mil pessoas à Praia Fluvial do Taboão. Depois do sucesso da edição de 2015, completamente esgotada, o Vodafone Paredes de Coura continuou a apostar nas melhorias na área do campismo e do anfiteatro natural, que viu o seu espaço ampliado, mas manteve a lotação, o que permitiu receber o público com um cuidado reforçado e proporcionar ainda mais conforto, condições de higiene e segurança. -

"Blessing for the Nations" in the Patriarchal Narratives

THE THFIIE OF "BLESSING FOR THE NATIONS" IN THE PATRIARCHAL NARRATIVES OF GENESIS A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Biblical Studies University of Sheffield Riang Chea CHEW October, 1982 x ACKNOWLEDGE1ETS To be able to complete the present study is in itself a reflection of the assistance I received. It is therefore with great pleasure I express my appreciation to Mr. David Clines, my supervisor and Reader of the Biblical Studies Department, for his perceptive guidance throughout the period of my research. His kind friendship, understanding, and sacrifice of time, all contributed greatly to the completion of this thesis. In additions I would also like to express my thanks to Drs. Philip Davies and David Gunn, both also of the Biblical Studies Department.. Dr. Davies supervised me and Dr. &unn kindly gave of his time to discuss part of my work, during Mr. CIines' sabbatical leave in 1980/81. A special word of thanks also goes to Mr. Ken Rawlins of Sheffield whom I burdened with the unenviable task of correcting my English. I, of course, remain responsible for all the unidiomatic use of English still present in the study. Without the financial support of the Langham Trust, the present course of studies waulci not have been started and completed. In this, the personal encouragement of the Rev. Dr. John Stott is especially acknowledged. In addition, a number of organisations and friends have also contributed to the cost of maintenance for my family over the past three years. Of these, special thanks go to the consistent support given by the Lee Foundation, Singapore, and the church of which I am a member, both in Singapore and in Sheffield. -

Cedars, February 14, 2008 Cedarville University

Masthead Logo Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Cedars 2-14-2008 Cedars, February 14, 2008 Cedarville University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/cedars Part of the Journalism Studies Commons, and the Organizational Communication Commons DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a platform for archiving the scholarly, creative, and historical record of Cedarville University. The views, opinions, and sentiments expressed in the articles published in the university’s student newspaper, Cedars (formerly Whispering Cedars), do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The uthora s of, and those interviewed for, the articles in this paper are solely responsible for the content of those articles. Please address questions to [email protected]. Recommended Citation Cedarville University, "Cedars, February 14, 2008" (2008). Cedars. 61. https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/cedars/61 This Issue is brought to you for free and open access by Footer Logo DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cedars by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CEDARS Live and Love Hart-less Pirate Industry 16 THE CURRENT 14 February 2008 A Valentine’s Day Volleyball head How a federal reminder that not coach Melissa crackdown could Korean Youth Passionate About Cellular Phones all romance is Hartman steps make your playlist Dispatches sweet & easy down worth millions -- Alyssa Weaver -- high-speed Internet, and touch technology You na and Sooin. Also, barcode images Staff Writer has recently become viable for the American may be placed on the phone. -

Prospec Or Four Key Things to Look out for This Competition ENT

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP The rP ospector Special Collections Department 1-17-2012 The rP ospector, January 17, 2012 UTEP Student Publications Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.utep.edu/prospector Part of the Journalism Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Comments: This file is rather large, with many images, so it may take a few minutes to download. Please be patient. Recommended Citation UTEP Student Publications, "The rP ospector, January 17, 2012" (2012). The Prospector. Paper 67. http://digitalcommons.utep.edu/prospector/67 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections Department at DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in The rP ospector by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Texas at El Paso · January 17, 2012 theassayer of student opinion www.utepprospector.com Student design wins Orbit Gum prospec or Four key things to look out for this competition ENT. 9 semester SPORTS 13 CHEWING ON $5000 Welcome back Miners! WHAT TO WATCH FOR Students struggle with financial burden As debt mounts, grad school seems to be a distant option BY JASMINE AGUILERA consideration credit card, mortgage “It’s quite upsetting when I meet The Prospector or car payments or any other debt someone who gets everything paid when awarding financial aid. for but slacks off and doesn’t appre- According to the Project on Stu- “Last semester, we paid for my ciate it,” De Leon said. “There are dent Debt, two-thirds of college classes with my mom’s credit card,” plenty of other people that actually graduates take out student loans and De Leon said. -

The Mars Volta and the Symbolic Boundaries of Progressive Rock

GENRE AND/AS DISTINCTION: THE MARS VOLTA AND THE SYMBOLIC BOUNDARIES OF PROGRESSIVE ROCK R. Justin Frankeny A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Musicology in the School of Music. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Aaron Harcus Michael A. Figueroa David F. Garcia © 2020 R. Justin Frankeny ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT R. Justin Frankeny: Genre and/as Distinction: The Mars Volta and the Symbolic Boundaries of Progressive Rock (Under the direction of Dr. Aaron Harcus) In the early 2000’s, The Mars Volta’s popularity among prog(ressive) rock fandom was, in many ways, a conundrum. Unlike 1970s prog rock that drew heavily on Western classical music, TMV members Omar Rodriguez-Lopez and Cedric Bixler-Zavala routinely insisted on the integral importance of salsa music to their style and asserted an ambivalent relationship to classic prog rock. This thesis builds on existing scholarship on cultural omnivorousness to assert that an increase in omnivorous musical tastes since prog rock’s inception in the 1970s not only explains The Mars Volta’s affiliation with the genre in the early 2000s, but also explains their mixed reception within a divided prog rock fanbase. Contrary to existing scholarship that suggests that the omnivore had largely supplanted the highbrow snob, this study suggests that the snob persisted in the prog rock fanbase during progressive rock’s resurgence (ca. 1997-2012), as distinguished by their assertion of the superiority of prog rock through discourses of musical complexity adapted from classical music. -

First Headliner Announced for Reading & Leeds Festival 2017 – a Uk Festival Exclusive

EMBARGOED UNTIL 7:45AM THURSDAY 1 DECEMBER 2016 PRESENTS 25TH – 27TH AUGUST 2017, BANK HOLIDAY WEEKEND FIRST HEADLINER ANNOUNCED FOR READING & LEEDS FESTIVAL 2017 – A UK FESTIVAL EXCLUSIVE MUSE MAJOR LAZER, BASTILLE, ARCHITECTS, TORY LANEZ, AT THE DRIVE-IN, GLASS ANIMALS, AGAINST THE CURRENT, ANDY C, DANNY BROWN AND WHILE SHE SLEEPS ALSO CONFIRMED HUNDREDS MORE TO BE ANNOUNCED FOR 2017 http://www.readingandleedsfestival.com Reading & Leeds Festivals announce Muse, in a UK festival exclusive, as the first headliners for next year’s festival, taking place 25-27 August 2017. Stadium rock royalty, Muse are one of the most influential and revered live bands of modern times. Led by the commanding presence of frontman Matt Bellamy, the trio have taken to the biggest stages around the world with their interstellar anthems for over 22 years, and their return to Reading & Leeds promises to be yet another landmark moment in their storied career. Muse commented: "We’re very excited to be playing Reading and Leeds again. More news about our plans for 2017 coming in the new year." Melvin Benn commented: “I’m thrilled to be able to announce Muse as the first headliner for Reading and Leeds 2017. Their incredible live show promises to be an unforgettable performance - we have so much more to announce and I can’t wait to reveal the rest of the line up.” Also confirmed for Reading & Leeds 2017 in a UK festival exclusive, are dancehall-rejuvenators Major Lazer. Diplo, Jillionaire and Walshy Fire have become the soundtrack of modern dance, claiming No.1 records, chart-dominating tracks such as ‘Lean On’ and ‘Cold Water’ as well as live shows packed with genre-mashing moments promising an unrivalled party atmosphere. -

Berkeley C.Pdf

Cardinal Classic XI Packet by Berkeley C Round 4 Tossups 1. He trudges Southern Street searching for a place where he may eat or rest, looking vainly for a job other than menial labor, feeling the "hate stare." (*) His effigy was hung from the center light on Main Street. Hate-filled people whispered that he had been a Negro all along. He is a white man who darkened the color of his skin. FTP, name this man, who retold these events and more in "Black Like Me." Answer: John Howard --Griffin 2. As a teenager he followed the political economy work of Smith and Ricardo, and in 1848 he published his Principles (*) of Political Economy. A disciple of Jeremy Bentham, he became a prominent proponent of utilitarianism. He also penned the treatise The Subjection of Women, manifesting his belief in women's rights. For ten points, name this English author of "On Liberty." Answer: John Stuart Mill 3. It is the complement to Norton's theorem, and states that a linear, (*) active, resistive network which contains independent voltage or current sources can be replaced by a single voltage source and a series resistance. FTP, what is this circuit analysis theorem, which greatly simplifies network analysis under various load conditions? Answer: Thevenin's theorem 4. On Dec 30th, 1853, Santa Anna made one of the biggest blunders of his political career. Because the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (*) left the western part of the U.S.-Mexico border disputed, and the United States wanted a southern railroad route to the Pacific, 29,640 square miles of land between the Gila River on the north and the current border were sold to the United States for 10 Million Dollars. -

ORDER FORM FULL Pdfcd

JAZZ ARTIST TITLE LABEL RETAIL BILK, ACKER STRANGER ON THE SHORE-BEST OF GNP CRESCENDO RM59.00 CAINE, ELLIOTT - SEXTET HIPPIE CHICKS ON ACID (LIVE AT ALVA WONDERCAP RM63.00 DJ BONEBRAKE TRIO THE OTHER OUTSIDE WONDERCAP RM63.00 GRADY, KRAIG BEYOND THE WINDOWS PERHAPS AMONG TH TRANSPARENCY RM48.00 HARLEY, RUFUS BAGPIPES OF THE WORLD TRANSPARENCY RM61.00 HARLEY, RUFUS RE-CREATION OF THE GODS TRANSPARENCY RM61.00 JONES, NORAH COME AWAY WITH ME (BONUS DISC) BLUE NOTE RM132.00 LEONARDSON, ERIC & STEVE BARSOTTI RAREBIT TRANSPARENCY RM48.00 LOS ANGELES FREE MUSIC SOCIETY THE BLORP ESETTE GAZETTE VOL.1 (FAL TRANSPARENCY RM61.00 LOS ANGELES FREE MUSIC SOCIETY THE BLORP ESETTE GAZETTE VOL.2 (WIN TRANSPARENCY RM61.00 MINGUS, CHARLES THE LEAVES JAZZ CAT RM67.00 MONK, THELONIOUS SOULVILLE JAZZ CAT RM67.00 MORGAN, LEE AFTER THE LIGHTS JAZZ CAT RM67.00 OMER, PIERRE - SWING REVUE SWING CREMONA VOODOO RHYTHM RM78.00 PATCHEN, KENNETH READS HIS POETRY WITH JAZZ TWO-BEAT BEATNK RM61.00 PUSSYWARMERS, THE THE CHRONICLES OF... VOODOO RHYTHM RM78.00 ROACH, MAX & CLIFFORD BROWN IN CONCERT GNP CRESCENDO RM59.00 ROYAL CROWN REVUE KINGS OF GANGSTER BOP BYO RM53.00 SUN RA DANCE OF THE LIVING IMAGE (L.R. 4) TRANSPARENCY RM61.00 SUN RA LIVE AT THE ELECTRIC CIRCUS/NEWPORT TRANSPARENCY RM62.00 SUN RA THE CREATOR OF THE UNIVERSE TRANSPARENCY RM61.00 SUN RA THE ROAD TO DESTINY (LOST REEL 6) TRANSPARENCY RM55.00 SUN RA THE SHADOWS TOOK SHAPE (LOST REEL 3 TRANSPARENCY RM61.00 SUN RA THE UNIVERSE SENT ME (LOST REEL 5) TRANSPARENCY RM55.00 SUN RA UNTITLED RECORDINGS TRANSPARENCY