Rebeco – Rupicapra Pyrenaica

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guidelines on Wilderness in Natura 2000

Technical Report - 2013 - 069 Guidelines on Wilderness in Natura 2000 Management of terrestrial wilderness and wild areas within the Natura 2000 Network Environment Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union New freephone number: 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 This document reflects the view of the Commission services and is not of a binding nature. ISBN 978-92-79-31157-4 doi: 10.2779/33572 © European Union, 2013 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged This document has been prepared with the assistance of Alterra in a consortium with PAN Parks Foundation and Eurosite under contract to the European Commission (contract N°07.0307/2010/576314/SER/B3). It has also greatly benefitted from discussions with, and information supplied by, experts from Member States, key stakeholder groups and the Expert Group on management of Natura 2000. Parts concerning national legislation and mapping have built on work done in the Wildland Research Institute, University of Leeds. Photograph cover page: Central Balkan, Natura 2000 site number BG 0000494 ©Svetoslav Spasov, who has kindly made this photo available to the European Commission for use in this guidance document EU Guidance on the management of wilderness and wild areas in Natura 2000 Contents Purpose of this Guidance 5 Background 5 Purpose of this guidance document 7 Structure and contents 7 Limitations of the document 8 1 What is wilderness in the context of Natura 2000? 10 1.1 Introduction 10 1.2 Definition of wilderness 10 1.2.1 -

Contributions to the 12Th Conference of the European Wildlife Disease Association (EWDA) August 27Th – 31St, 2016, Berlin

12th Conference of the European Wildlife Disease Association (EWDA), Berlin 2016 Contributions to the 12th Conference of the European Wildlife Disease Association (EWDA) August 27th – 31st, 2016, Berlin, Germany Edited by Anke Schumann, Gudrun Wibbelt, Alex D. Greenwood, Heribert Hofer Organised by Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research (IZW) Alfred-Kowalke-Straße 17 10315 Berlin Germany www.izw-berlin.de and the European Wildlife Disease Association (EWDA) https://sites.google.com/site/ewdawebsite/ & ISBN 978-3-9815637-3-3 12th Conference of the European Wildlife Disease Association (EWDA), Berlin 2016 Published by Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research (IZW) Alfred-Kowalke-Str. 17, 10315 Berlin (Friedrichsfelde) PO Box 700430, 10324 Berlin, Germany Supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) [German Research Foundation] Kennedyallee 40, 53175 Bonn, Germany Printed on Forest Stewardship Council certified paper All rights reserved, particularly those for translation into other languages. It is not permitted to reproduce any part of this book by photocopy, microfilm, internet or any other means without written permission of the IZW. The use of product names, trade names or other registered entities in this book does not justify the assumption that these can be freely used by everyone. They may represent registered trademarks or other legal entities even if they are not marked as such. Processing of abstracts: Anke Schumann, Gudrun Wibbelt Setting and layout: Anke Schumann, Gudrun Wibbelt Cover: Diego Romero, Steven Seet, Gudrun Wibbelt Word cloud: ©Tagul.com Printing: Spree Druck Berlin GmbH www.spreedruck.de Order: Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research (IZW) Forschungsverbund Berlin e.V. PO Box 700430, 10324 Berlin, Germany [email protected] www.izw-berlin.de 12th Conference of the European Wildlife Disease Association (EWDA), Berlin 2016 CONTENTS Foreword ................................................................................................................. -

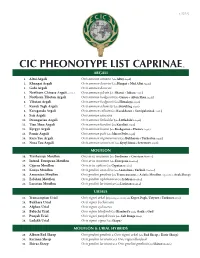

Cic Pheonotype List Caprinae©

v. 5.25.12 CIC PHEONOTYPE LIST CAPRINAE © ARGALI 1. Altai Argali Ovis ammon ammon (aka Altay Argali) 2. Khangai Argali Ovis ammon darwini (aka Hangai & Mid Altai Argali) 3. Gobi Argali Ovis ammon darwini 4. Northern Chinese Argali - extinct Ovis ammon jubata (aka Shansi & Jubata Argali) 5. Northern Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Gansu & Altun Shan Argali) 6. Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Himalaya Argali) 7. Kuruk Tagh Argali Ovis ammon adametzi (aka Kuruktag Argali) 8. Karaganda Argali Ovis ammon collium (aka Kazakhstan & Semipalatinsk Argali) 9. Sair Argali Ovis ammon sairensis 10. Dzungarian Argali Ovis ammon littledalei (aka Littledale’s Argali) 11. Tian Shan Argali Ovis ammon karelini (aka Karelini Argali) 12. Kyrgyz Argali Ovis ammon humei (aka Kashgarian & Hume’s Argali) 13. Pamir Argali Ovis ammon polii (aka Marco Polo Argali) 14. Kara Tau Argali Ovis ammon nigrimontana (aka Bukharan & Turkestan Argali) 15. Nura Tau Argali Ovis ammon severtzovi (aka Kyzyl Kum & Severtzov Argali) MOUFLON 16. Tyrrhenian Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka Sardinian & Corsican Mouflon) 17. Introd. European Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka European Mouflon) 18. Cyprus Mouflon Ovis aries ophion (aka Cyprian Mouflon) 19. Konya Mouflon Ovis gmelini anatolica (aka Anatolian & Turkish Mouflon) 20. Armenian Mouflon Ovis gmelini gmelinii (aka Transcaucasus or Asiatic Mouflon, regionally as Arak Sheep) 21. Esfahan Mouflon Ovis gmelini isphahanica (aka Isfahan Mouflon) 22. Larestan Mouflon Ovis gmelini laristanica (aka Laristan Mouflon) URIALS 23. Transcaspian Urial Ovis vignei arkal (Depending on locality aka Kopet Dagh, Ustyurt & Turkmen Urial) 24. Bukhara Urial Ovis vignei bocharensis 25. Afghan Urial Ovis vignei cycloceros 26. -

Spatial Patterns of Mitochondrial and Nuclear Gene Pools in Chamois (Rupicapra R

Heredity (2003) 91, 125–135 & 2003 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0018-067X/03 $25.00 www.nature.com/hdy Spatial patterns of mitochondrial and nuclear gene pools in chamois (Rupicapra r. rupicapra) from the Eastern Alps H Schaschl, D Kaulfus, S Hammer1 and F Suchentrunk Research Institute of Wildlife Ecology, Veterinary Medicine University of Vienna, Savoyenstrasse 1, A-1160 Vienna, Austria We have assessed the variability of maternally (mtDNA) and variability as a result of immigration of chamois from different biparentally (allozymes) inherited genes of 443 chamois Pleistocene refugia surrounding the Alps after the withdrawal (Rupicapra r. rupicapra) from 19 regional samples in the of glaciers, rather than from topographic barriers to gene Eastern Alps, to estimate the degree and patterns of spatial flow, such as Alpine valleys, extended glaciers or woodlands. gene pool differentiation, and their possible causes. Based However, this striking geographical structuring of the on a total mtDNA-RFLP approach with 16 hexanucleotide- maternal genome was not paralleled by allelic variation at recognizing restriction endonucleases, we found marked 33 allozyme loci, which were used as nuclear DNA markers. substructuring of the maternal gene pool into four phylogeo- Wright’s hierarchical F-statistics revealed that only p0.45% of graphic groups. A hierarchical AMOVA revealed that 67.09% the explained allozymic diversity was because of partitioning of the variance was partitioned among these four mtDNA- among the four mtDNA-phylogroups. We conclude that this phylogroups, whereas only 8.04% were because of partition- discordance of spatial patterns of nuclear and mtDNA gene ing among regional samples within the populations, and pools results from a phylogeographic background and sex- 24.86% due to partitioning among individuals within regional specific dispersal, with higher levels of philopatry in females. -

Population Structure and Genetic Diversity of Non-Native Aoudad

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Population structure and genetic diversity of non‑native aoudad populations Sunčica Stipoljev1, Toni Safner 2,3*, Pavao Gančević1, Ana Galov 4, Tina Stuhne1, Ida Svetličić4, Stefano Grignolio 5, Jorge Cassinello 6 & Nikica Šprem 1 The aoudad (Ammotragus lervia Pallas 1777) is an ungulate species, native to the mountain ranges of North Africa. In the second half of the twentieth century, it was successfully introduced in some European countries, mainly for hunting purposes, i.e. in Croatia, the Czech Republic, Italy, and Spain. We used neutral genetic markers, the mitochondrial DNA control region sequence and microsatellite loci, to characterize and compare genetic diversity and spatial pattern of genetic structure on diferent timeframes among all European aoudad populations. Four distinct control region haplotypes found in European aoudad populations indicate that the aoudad has been introduced in Europe from multiple genetic sources, with the population in the Sierra Espuña as the only population in which more than one haplotype was detected. The number of detected microsatellite alleles within all populations (< 3.61) and mean proportion of shared alleles within all analysed populations (< 0.55) indicates relatively low genetic variability, as expected for new populations funded by a small number of individuals. In STRU CTU RE results with K = 2–4, Croatian and Czech populations cluster in the same genetic cluster, indicating joined origin. Among three populations from Spain, Almeria population shows as genetically distinct from others in results, while other Spanish populations diverge at K = 4. Maintenance of genetic diversity should be included in the management of populations to sustain their viability, specially for small Czech population with high proportion of shared alleles (0.85) and Croatian population that had the smallest estimated efective population size (Ne = 5.4). -

Temporal Variation in Foraging Activity and Grouping Patterns in a Mountain-Dwelling Herbivore Environmental and Endogenous

Behavioural Processes 167 (2019) 103909 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Behavioural Processes journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/behavproc Temporal variation in foraging activity and grouping patterns in a mountain-dwelling herbivore: Environmental and endogenous drivers T ⁎ Niccolò Fattorinia, , Claudia Brunettia, Carolina Baruzzia, Gianpasquale Chiatanteb, Sandro Lovaria,c, Francesco Ferrettia a Department of Life Sciences, University of Siena. Via P.A. Mattioli 4, 53100 Siena, Italy b Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Pavia, Via Ferrata 1, 27100 Pavia, Italy c Maremma Natural History Museum, Strada Corsini 5, 58100 Grosseto, Italy ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: In temperate ecosystems, seasonality influences animal behaviour. Food availability, weather, photoperiod and Seasonality endogenous factors relevant to the biological cycle of individuals have been shown as major drivers of temporal Foraging Activity changes in activity rhythms and group size/structure of herbivorous species. We evaluated how diurnal female Group size foraging activity and grouping patterns of a mountain herbivore, the Apennine chamois Rupicapra pyrenaica Rupicapra ornata, varied during a decreasing gradient of pasture availability along the summer-autumn progression Chamois (July–October), a crucial period for the life cycle of mountain ungulates. Mountain herbivores Females increased diurnal foraging activity, possibly because of constrains elicited by variation in environ- mental factors. Size of mixed groups did not vary, in contrast with the hypothesis that groups should be smaller when pasture availability is lower. Proportion of females in groups increased, possibly suggesting that they concentrated on patchily distributed nutritious forbs. Occurrence of yearlings in groups decreased, which may have depended on dispersal of chamois in this age class. -

Diversity and Evolution of the Mhc-DRB1 Gene in the Two Endemic Iberian Subspecies of Pyrenean Chamois, Rupicapra Pyrenaica

Heredity (2007) 99, 406–413 & 2007 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0018-067X/07 $30.00 www.nature.com/hdy ORIGINAL ARTICLE Diversity and evolution of the Mhc-DRB1 gene in the two endemic Iberian subspecies of Pyrenean chamois, Rupicapra pyrenaica J Alvarez-Busto1, K Garcı´a-Etxebarria1, J Herrero2,3, I Garin4 and BM Jugo1 1Genetika, Antropologia Fisikoa eta Animali Fisiologia Saila, Zientzia eta Teknologia Fakultatea, Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea (UPV/EHU), Bilbao, Spain; 2Departamento de Ecologı´a, Universidad de Alcala´ de Henares, Alcala´ de Henares, Spain; 3EGA Wildlife Consultants, Zaragoza, Spain and 4Zoologı´a eta Animali Zelulen Biologia Saila, Zientzia eta Teknologia Fakultatea, Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea (UPV/EHU), Bilbao, Spain Major histocompatibility complex class II locus DRB variation recent parasitic infections by sarcoptic mange. A phyloge- was investigated by single-strand conformation polymorph- netic analysis of both Pyrenean chamois and DRB alleles ism analysis and sequence analysis in the two subspecies of from 10 different caprinid species revealed that the chamois Pyrenean chamois (Rupicapra pyrenaica) endemic to the alleles form two monophyletic groups. In comparison with Iberian Peninsula. Low levels of genetic variation were other Caprinae DRB sequences, the Rupicapra alleles detected in both subspecies, with seven different alleles in R. displayed a species-specific clustering that reflects a large p. pyrenaica and only three in the R. p. parva. After applying temporal divergence of the chamois from other caprinids, as the rarefaction method to cope with the differences in sample well as a possible difference in the selective environment for size, the low allele number of parva was highlighted. -

Infectious Keratoconjunctivitis at the Wildlife-Livestock Interface from Mountain Systems: Dynamics, Functional Roles and Host-Mycoplasma Interactions

ADVERTIMENT. Lʼaccés als continguts dʼaquesta tesi queda condicionat a lʼacceptació de les condicions dʼús establertes per la següent llicència Creative Commons: http://cat.creativecommons.org/?page_id=184 ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis queda condicionado a la aceptación de las condiciones de uso establecidas por la siguiente licencia Creative Commons: http://es.creativecommons.org/blog/licencias/ WARNING. The access to the contents of this doctoral thesis it is limited to the acceptance of the use conditions set by the following Creative Commons license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/?lang=en Infectious keratoconjunctivitis at the wildlife‐livestock interface from mountain systems Dynamics, functional roles and host‐ mycoplasma interactions Xavier Fernández Aguilar PHD Thesis Infectious keratoconjunctivitis at the wildlife-livestock interface from mountain systems: dynamics, functional roles and host-mycoplasma interactions Xavier Fernández Aguilar Directors Jorge Ramón López Olvera Óscar Cabezón Ponsoda Tesi Doctoral Departament de Medicina i Cirurgia Animals Facultat de Vetarinària Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona 2017 Drawings and pictures of this thesis are from the author except for: page 31, top: Radomir Jakubowski; page 37, top: Fernando Mostacero; page 48; figure 2.11 C: Arturo Galvez ; page 49, figure 2.12 C: Patrick Deleury, D: Santiago Lavín; page 63, figure 2.15 A, C: Etienne Florence and B, D: Jean Paul Crampe and E: Benoît Dandonneau; page 105, figure 4.2.2: Luca Rossi; page 133, figure 4.3.6: -

Tatra National Park Between Poland & Slovakia

Sentinel Vision EVT-623 Tatra National Park between Poland & Slovakia 12 March 2020 Sentinel-2 MSI acquired on 20 April 2019 at 09:40:39 UTC Sentinel-1 CSAR IW acquired on 20 August 2019 at 04:53:23 UTC Sentinel-2 MSI acquired on 22 September 2019 at 09:40:31 UTC Author(s): Sentinel Vision team, VisioTerra, France - [email protected] Keyword(s): Mountain range, national park, UNESCO biosphere reserve, forestry, glacial lake, glacier, biosphere, wetland, 2D Layerstack peatland, bog, Slovakia, Poland, Carpathians Fig. 1 - S2 (22.09.2019) - 12,11,2 colour composite - Tatra National Park is a mountainous park located both in Slovakia and in Poland. 2D view Fig. 2 - S2 (20.04.2019) - 4,3,2 natural colour - It lies at the northernmost & westernmost stretches of the Carpathian range. 2D view / Tatra National Park is a mountainous park located both in Slovakia and in Poland. It includes valleys, meadows and dense forests, as well as caves. There are tenths of mountain lakes, the largest of which are Morskie Oko and Wielki, located in the Five Lakes Valley. The Chocholow Valley meadow is the largest of the Polish Tatras, and is one of the main mountain pastures in the region. Many torrents give rise to waterfalls, including the Wielka Siklawa, literally "the big waterfall", which jumps 70 meters. The TAtra NAtional Park (TANAP, Slovak side) was established in 1949 and is the oldest of the Slovak national parks. The Tatra National Park (TPN, Polish side) was created in 1954, by decision of the Polish Government. Since 1993, TANAP and TPN (Polish side) have together constituted a UNESCO transboundary biosphere reserve. -

Monitoring of Pseudotuberculosis in an Italian Population of Alpine

ary Scien in ce r te & e T V e Besozzi et al., J Vet Sci Technol 2017, 8:5 f c h o Journal of Veterinary Science & n n l o o a a DOI: 10.4172/2157-7579.1000475 l l n n o o r r g g u u y y o o J J Technology ISSN: 2157-7579 Research Article Open Access Monitoring of pseudotuberculosis in an Italian Population of Alpine Chamois: Preliminary Results Martina Besozzi1*, Emiliana Ballocchi2, Pierluigi Cazzola2 and Roberto Viganò1 1Study Associate AlpVet, Piazza Venzaghi, 2-21052 Busto Arsizio (VA), Italy 2IZSPLV Section of Vercelli, Via Cavalcanti, 59-13100 Vercelli, Italy *Corresponding author: Martina Besozzi, Study Associate AlpVet, Piazza Venzaghi, 2-21052 Busto Arsizio (VA), Italy, Tel: +393493556003; E-mail: [email protected] Rec date: September 26, 2017; Acc date: October 04, 2017; Pub date: October 05, 2017 Copyright: © 2017 Besozzi M, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Caseous lymphadenitis (CLA) of sheep and goats is a chronic and often sub-clinical disease, with high prevalence in different parts of the world, which can caused significant economic losses for farmers. The causative agent is Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis that primarily infects domestic small ruminants, but it has been isolated also in wildlife such as pronghorns (Antilocapra americana) and elk (Cervus elaphus canadensis). Furthermore, a recent research has demonstrated a maintenance of the infection on an endemic level in a Spanish ibex (Capra pyrenaica hispanica) population after an outbreak with high morbidity and mortality. -

Genotyping of Pestivirus a (Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus 1) Detected in Faeces and in Other Specimens of Domestic and Wild Rumina

Veterinary Microbiology 235 (2019) 180–187 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Veterinary Microbiology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/vetmic Genotyping of Pestivirus A (Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus 1) detected in faeces T and in other specimens of domestic and wild ruminants at the wildlife- livestock interface ⁎ Sara Riccia,1,2, Sofia Bartolinia,1,2, Federico Morandib, Vincenzo Cuteria, Silvia Preziusoa, a School of Biosciences and Veterinary Medicine, University of Camerino, Italy b National Park of Monti Sibillini, Visso, MC, Italy ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Pestiviruses are widespread in the world among ungulates and infect both domestic and wild animals causing Pestivirus A severe economic losses in livestock. Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus type 1 (BVDV-1), now re-designated as Pestivirus BVDV-1 A, causes diseases mainly in cattle, while few data are available about infection in wild ruminants and about the Genetic typing role of these animals in viral maintenance and spread. In order to investigate BVDV-1 infection in domestic and Domestic and wild ruminants wild ruminants, especially at the wildlife/livestock interface, bulk tank milk from dairy cattle and sheep and Faeces spleen from red deer, roe deer and fallow deer were analysed. Furthermore, faecal samples from Apennine chamois and from wild deer were evaluated as a suitable sample for detecting and genotyping pestiviruses. BVDV-1 RNA was found in all animal species tested but not sheep. Genotyping based on partial 5′UTR and Npro sequences detected BVDV-1a in samples from Apennine chamois, red deer, roe deer and pasture-raised cattle, while BVDV-1c was found in a faecal sample from Apennine chamois and in a spleen sample from roe deer. -

Seasonal Variation in Group Size of Cantabrian Chamois in Relation to Escape Terrain and Food

Acta Theriologica 39 (3): 295-305,1994. PL ISSN 0001-7051' Seasonal variation in group size of Cantabrian chamois in relation to escape terrain and food F. Javier PÉREZ-BARBERÍA and Carlos NORES Pérez-Barbería F. J. and Ñores C. 1994. Seasonal variation in group size of Cantabrian chamois in relation to escape terrain and food. Acta theriol. 39: 295-305. The herd size of Cantabrian chamois Rupicapra pyrenaica parva (Cabrera, 1910) varied seasonally in relation to escape terrain and food availability in our study area (Asturias, north of Spain). The median group size of females without kids was 1 (mean ± SD = 1.62 ± 1.00), females with kids was 4 (5.59 ± 5.42), males was 1 (1.73 ± 1.78), and mixed group size was 7 (8.91 ± 7.91). The female-kid group size depended more on escape terrain availability than on food quality. Throughout the early weeks of the life of kids, the mothers remained in difficult access areas (cliffs and steep slopes), and showed a weak tendency to aggregate. These areas provided a wide visual range and hiding places for offspring and their use may be an anti-predation strategy. When the kids were able to run quickly, the mothers used subalpine meadows. These areas were very open and exposed kids to predation and human disturbance, however the forage has high nutritive value, and may compensate for the cost of breeding and suckling by the mothers. Aggregation may be selected as an anti-predation strategy in subalpine meadows, allowing a reduction in time spent vigilant by each individual in the group, and increased time available for other activities.