Rarity, Trophy Hunting and Ungulates L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inclusion of Asiatic Mammal Species on Cms Appendices

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals Secretariat provided by the United Nations Environment Programme 14 th MEETING OF THE CMS SCIENTIFIC COUNCIL Bonn, Germany, 14-17 March 2007 CMS/ScC14/Doc.13 Agenda item 6(a) DRAFT PROPOSALS FOR THE INCLUSION OF ASIATIC MAMMAL SPECIES ON CMS APPENDICES (Prepared by the Secretariat) 1. The four draft proposals for the amendment of CMS Appendices attached to this note have been prepared by the Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique and have been submitted by Dr. Pierre Devillers, Scientific Councillor for the European Community and vice-chairman of the Scientific Council. 2. Preparation of these draft proposals is undertaken within the Central Eurasian Aridland Concerted Action and associated Cooperative Action approved by the 8 th Meeting of the Conference of the Parties to CMS (Recommendation 8.23), covering threatened migratory large mammals of the temperate and cold deserts, semi-deserts, steppes and associated mountains of Central Asia, the Northern Indian sub-continent, Western Asia, the Caucasus and Eastern Europe. 3. In particular, Rec. 8.23 “encourages Range States and other interested Parties to prepare, in cooperation with the Scientific Council and the Secretariat, the necessary proposals to include in Appendix I or Appendix II threatened species that would benefit from the Action”. For reasons of economy, documents are printed in a limited number, and will not be distributed at the meeting. Delegates are kindly requested to bring their copy to the meeting and not to request additional copies. DRAFT PROPOSAL FOR INCLUSION OF SPECIES ON THE APPENDICES OF THE CONVENTION ON THE CONSERVATION OF MIGRATORY SPECIES OF WILD ANIMALS Proposal to add in Appendix I Pantholops hodgsonii Document largely based on the species information provided in IUCN Redlist of Threatened Species database (2006) February 2007 2 1. -

Benin 2019 - 2020

BENIN 2019 - 2020 West African Savannah Buffalo Western Roan Antelope For more than twenty years, we have been organizing big game safaris in the north of the country on the edge of the Pendjari National Park, in the Porga hunting zone. The hunt is physically demanding and requires hunters to be in good physical condition. It is primary focused on hunting Roan Antelopes, West Savannah African Buffaloes, Western Kobs, Nagor Reedbucks, Western Hartebeests… We shoot one good Lion every year, hunted only by tracking. Baiting is not permitted. Accommodation is provided in a very confortable tented camp offering a spectacular view on the bush.. Hunting season: from the beginning of January to mid-May. - 6 days safari: each hunter can harvest 1 West African Savannah Buffalo, 1 Roan Antelope or 1 Western Hartebeest, 1 Nagor Reedbuck or 1 Western Kob, 1 Western Bush Duiker, 1 Red Flanked Duiker, 1 Oribi, 1 Harnessed Bushbuck, 1 Warthog and 1 Baboon. - 13 and 20 days safari: each hunter can harvest 1 Lion (if available at the quota), 1 West African Savannah Buffalo, 1 Roan Antelope, 1 Sing Sing Waterbuck, 1 Hippopotamus, 1 Western Hartebeest, 1 Nagor Reedbuck, 1 Western Kob, 1 Western Bush Duiker, 1 Red Flanked Duiker, 1 Oribi, 1 Harnessed Bushbuck, 1 Warthog and 1 Baboon. Prices in USD: Price of the safari per person 6 hunting days 13 hunting days 20 hunting days 2 Hunters x 1 Guide 8,000 16,000 25,000 1 Hunter x 1 Guide 11,000 24,000 36,000 Observer 3,000 4,000 5,000 The price of the safari includes: - Meet and greet plus assistance at Cotonou airport (Benin), - Transfer from Cotonou to the hunting area and back by car, - The organizing of your safari with 4x4 vehicles, professional hunters, trackers, porters, skinners, - Full board accommodation and drinks at the hunting camp. -

Pending World Record Waterbuck Wins Top Honor SC Life Member Susan Stout Has in THIS ISSUE Dbeen Awarded the President’S Cup Letter from the President

DSC NEWSLETTER VOLUME 32,Camp ISSUE 5 TalkJUNE 2019 Pending World Record Waterbuck Wins Top Honor SC Life Member Susan Stout has IN THIS ISSUE Dbeen awarded the President’s Cup Letter from the President .....................1 for her pending world record East African DSC Foundation .....................................2 Defassa Waterbuck. Awards Night Results ...........................4 DSC’s April Monthly Meeting brings Industry News ........................................8 members together to celebrate the annual Chapter News .........................................9 Trophy and Photo Award presentation. Capstick Award ....................................10 This year, there were over 150 entries for Dove Hunt ..............................................12 the Trophy Awards, spanning 22 countries Obituary ..................................................14 and almost 100 different species. Membership Drive ...............................14 As photos of all the entries played Kid Fish ....................................................16 during cocktail hour, the room was Wine Pairing Dinner ............................16 abuzz with stories of all the incredible Traveler’s Advisory ..............................17 adventures experienced – ibex in Spain, Hotel Block for Heritage ....................19 scenic helicopter rides over the Northwest Big Bore Shoot .....................................20 Territories, puku in Zambia. CIC International Conference ..........22 In determining the winners, the judges DSC Publications Update -

Aerial Surveys of Wildlife and Human Activity Across the Bouba N'djida

Aerial Surveys of Wildlife and Human Activity Across the Bouba N’djida - Sena Oura - Benoue - Faro Landscape Northern Cameroon and Southwestern Chad April - May 2015 Paul Elkan, Roger Fotso, Chris Hamley, Soqui Mendiguetti, Paul Bour, Vailia Nguertou Alexandre, Iyah Ndjidda Emmanuel, Mbamba Jean Paul, Emmanuel Vounserbo, Etienne Bemadjim, Hensel Fopa Kueteyem and Kenmoe Georges Aime Wildlife Conservation Society Ministry of Forests and Wildlife (MINFOF) L'Ecole de Faune de Garoua Funded by the Great Elephant Census Paul G. Allen Foundation and WCS SUMMARY The Bouba N’djida - Sena Oura - Benoue - Faro Landscape is located in north Cameroon and extends into southwest Chad. It consists of Bouba N’djida, Sena Oura, Benoue and Faro National Parks, in addition to 25 safari hunting zones. Along with Zakouma NP in Chad and Waza NP in the Far North of Cameroon, the landscape represents one of the most important areas for savanna elephant conservation remaining in Central Africa. Aerial wildlife surveys in the landscape were first undertaken in 1977 by Van Lavieren and Esser (1979) focusing only on Bouba N’djida NP. They documented a population of 232 elephants in the park. After a long period with no systematic aerial surveys across the area, Omondi et al (2008) produced a minimum count of 525 elephants for the entire landscape. This included 450 that were counted in Bouba N’djida NP and its adjacent safari hunting zones. The survey also documented a high richness and abundance of other large mammals in the Bouba N’djida NP area, and to the southeast of Faro NP. In the period since 2010, a number of large-scale elephant poaching incidents have taken place in Bouba N’djida NP. -

Tibet's Biodiversity

Published in (Pages 40-46): Tibet’s Biodiversity: Conservation and Management. Proceedings of a Conference, August 30-September 4, 1998. Edited by Wu Ning, D. Miller, Lhu Zhu and J. Springer. Tibet Forestry Department and World Wide Fund for Nature. China Forestry Publishing House. 188 pages. People-Wildlife Conflict Management in the Qomolangma Nature Preserve, Tibet. By Rodney Jackson, Senior Associate for Ecology and Biodiversity Conservation, The Mountain Institute, Franklin, West Virginia And Conservation Director, International Snow Leopard Trust, Seattle, Washington Presented at: Tibet’s Biodiversity: Conservation and Management. An International Workshop, Lhasa, August 30 - September 4, 1998. 1. INTRODUCTION Established in March 1989, the Qomolangma Nature Preserve (QNP) occupies 33,819 square kilometers around the world’s highest peak, Mt. Everest known locally as Chomolangma. QNP is located at the junction of the Palaearctic and IndoMalayan biogeographic realms, dominated by Tibetan Plateau and Himalayan Highland ecoregions. Species diversity is greatly enhanced by the extreme elevational range and topographic variation related to four major river valleys which cut through the Himalaya south into Nepal. Climatic conditions differ greatly from south to north as well as in an east to west direction, due to the combined effect of exposure to the monsoon and mountain-induced rain s- hadowing. Thus, southerly slopes are moist and warm while northerly slopes are cold and arid. Li Bosheng (1994) reported on biological zonation and species richness within the QNP. Surveys since the 1970's highlight its role as China’s only in-situ repository of central Himalayan ecosystems and species with Indian subcontinent affinities. Most significant are the temperate coniferous and mixed broad-leaved forests with their associated fauna that occupy the deep gorges of the Pungchu, Rongshar, Nyalam (Bhote Kosi) and Kyirong (Jilong) rivers. -

Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus

STATUS AND PROTECTION OF GLOBALLY THREATENED SPECIES IN THE CAUCASUS CEPF Biodiversity Investments in the Caucasus Hotspot 2004-2009 Edited by Nugzar Zazanashvili and David Mallon Tbilisi 2009 The contents of this book do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of CEPF, WWF, or their sponsoring organizations. Neither the CEPF, WWF nor any other entities thereof, assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, product or process disclosed in this book. Citation: Zazanashvili, N. and Mallon, D. (Editors) 2009. Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus. Tbilisi: CEPF, WWF. Contour Ltd., 232 pp. ISBN 978-9941-0-2203-6 Design and printing Contour Ltd. 8, Kargareteli st., 0164 Tbilisi, Georgia December 2009 The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank. This book shows the effort of the Caucasus NGOs, experts, scientific institutions and governmental agencies for conserving globally threatened species in the Caucasus: CEPF investments in the region made it possible for the first time to carry out simultaneous assessments of species’ populations at national and regional scales, setting up strategies and developing action plans for their survival, as well as implementation of some urgent conservation measures. Contents Foreword 7 Acknowledgments 8 Introduction CEPF Investment in the Caucasus Hotspot A. W. Tordoff, N. Zazanashvili, M. Bitsadze, K. Manvelyan, E. Askerov, V. Krever, S. Kalem, B. Avcioglu, S. Galstyan and R. Mnatsekanov 9 The Caucasus Hotspot N. -

The Eastern Cape –

The Eastern Cape – Revisited By Jeff Belongia A return to South Africa’s Eastern Cape was inevitable – the idea already firmly planted in my mind since my first visit in 1985. Africa, in general, has a wonderful yet strange control over the soul, and many writers have tried to express the reasoning behind it. I note this captivation and recognize the allure, and am too weak to resist. For me, Africa is what dreams are made of – and I dream of it daily. Dr. Martin Luther King was wise when he chose the phrase, “I have a dream.” He could have said, “I have a strategic plan.” Not quite the same effect! People follow their dreams. As parents we should spend more time teaching our children to dream, and to dream big. There is no Standard Operating Procedure to get through the tough times in life. Strength and discipline are measured by the depth and breadth of our dreams and not by strategic planning! The Catholic nuns at Saint Peter’s grade school first noted my talents. And they all told me to stop daydreaming. But I’ve never been able to totally conquer that urge – I dream continually of the romance of Africa, including the Eastern Cape. The Eastern Cape is a special place with a wide variety of antelope – especially those ‘pygmy’ species found nowhere else on the continent: Cape grysbok, blue duiker, Vaal rhebok, steenbok, grey duiker, suni, and oribi. Still not impressed? Add Cape bushbuck, mountain reedbuck, blesbok, nyala, bontebok, three colour phases of the Cape springbok, and great hunting for small cats such as caracal and serval. -

Contributions to the 12Th Conference of the European Wildlife Disease Association (EWDA) August 27Th – 31St, 2016, Berlin

12th Conference of the European Wildlife Disease Association (EWDA), Berlin 2016 Contributions to the 12th Conference of the European Wildlife Disease Association (EWDA) August 27th – 31st, 2016, Berlin, Germany Edited by Anke Schumann, Gudrun Wibbelt, Alex D. Greenwood, Heribert Hofer Organised by Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research (IZW) Alfred-Kowalke-Straße 17 10315 Berlin Germany www.izw-berlin.de and the European Wildlife Disease Association (EWDA) https://sites.google.com/site/ewdawebsite/ & ISBN 978-3-9815637-3-3 12th Conference of the European Wildlife Disease Association (EWDA), Berlin 2016 Published by Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research (IZW) Alfred-Kowalke-Str. 17, 10315 Berlin (Friedrichsfelde) PO Box 700430, 10324 Berlin, Germany Supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) [German Research Foundation] Kennedyallee 40, 53175 Bonn, Germany Printed on Forest Stewardship Council certified paper All rights reserved, particularly those for translation into other languages. It is not permitted to reproduce any part of this book by photocopy, microfilm, internet or any other means without written permission of the IZW. The use of product names, trade names or other registered entities in this book does not justify the assumption that these can be freely used by everyone. They may represent registered trademarks or other legal entities even if they are not marked as such. Processing of abstracts: Anke Schumann, Gudrun Wibbelt Setting and layout: Anke Schumann, Gudrun Wibbelt Cover: Diego Romero, Steven Seet, Gudrun Wibbelt Word cloud: ©Tagul.com Printing: Spree Druck Berlin GmbH www.spreedruck.de Order: Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research (IZW) Forschungsverbund Berlin e.V. PO Box 700430, 10324 Berlin, Germany [email protected] www.izw-berlin.de 12th Conference of the European Wildlife Disease Association (EWDA), Berlin 2016 CONTENTS Foreword ................................................................................................................. -

Central Eurasian Aridland Mammals Action Plan

CMS CONVENTION ON Distr. General MIGRATORY UNEP/CMS/ScC17/Doc.13 SPECIES 8 November 2011 Original: English 17 th MEETING OF THE SCIENTIFIC COUNCIL Bergen, 17-18 November 2011 Agenda Item 17.3.6 CENTRAL EURASIAN ARIDLAND MAMMALS ACTION PLAN (Prepared by the Secretariat) Following COP Recommendation 9.1 the Secretariat has prepared a draft Action Plan to complement the Concerted and Cooperative Action for Central Eurasian Aridland Mammals. The document is a first draft, intended to stimulate discussion and identify further action needed to finalize the document in consultation with the Range States and other stakeholders, and to agree on next steps towards its implementation. Action requested: The 17 th Meeting of the Scientific Council is invited to: a. Take note of the document and provide guidance on its further development and implementation; b. Review and advise in particular on the definition of the geographic scope, including the range states, and the target species (listed in table 1); and c. Provide guidance on the terminology currently used for the Action Plan, agree on a definition of the term aridlands and/or consider using the term drylands instead. Central Eurasian Aridland Mammals Draft Action Plan Produced by the UNEP/CMS Secretariat November 2011 1 Content 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Vision and Main Priority Directions ................................................................................................... -

Cic Pheonotype List Caprinae©

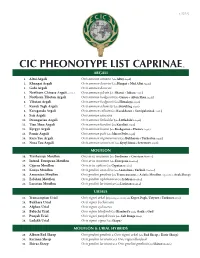

v. 5.25.12 CIC PHEONOTYPE LIST CAPRINAE © ARGALI 1. Altai Argali Ovis ammon ammon (aka Altay Argali) 2. Khangai Argali Ovis ammon darwini (aka Hangai & Mid Altai Argali) 3. Gobi Argali Ovis ammon darwini 4. Northern Chinese Argali - extinct Ovis ammon jubata (aka Shansi & Jubata Argali) 5. Northern Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Gansu & Altun Shan Argali) 6. Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Himalaya Argali) 7. Kuruk Tagh Argali Ovis ammon adametzi (aka Kuruktag Argali) 8. Karaganda Argali Ovis ammon collium (aka Kazakhstan & Semipalatinsk Argali) 9. Sair Argali Ovis ammon sairensis 10. Dzungarian Argali Ovis ammon littledalei (aka Littledale’s Argali) 11. Tian Shan Argali Ovis ammon karelini (aka Karelini Argali) 12. Kyrgyz Argali Ovis ammon humei (aka Kashgarian & Hume’s Argali) 13. Pamir Argali Ovis ammon polii (aka Marco Polo Argali) 14. Kara Tau Argali Ovis ammon nigrimontana (aka Bukharan & Turkestan Argali) 15. Nura Tau Argali Ovis ammon severtzovi (aka Kyzyl Kum & Severtzov Argali) MOUFLON 16. Tyrrhenian Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka Sardinian & Corsican Mouflon) 17. Introd. European Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka European Mouflon) 18. Cyprus Mouflon Ovis aries ophion (aka Cyprian Mouflon) 19. Konya Mouflon Ovis gmelini anatolica (aka Anatolian & Turkish Mouflon) 20. Armenian Mouflon Ovis gmelini gmelinii (aka Transcaucasus or Asiatic Mouflon, regionally as Arak Sheep) 21. Esfahan Mouflon Ovis gmelini isphahanica (aka Isfahan Mouflon) 22. Larestan Mouflon Ovis gmelini laristanica (aka Laristan Mouflon) URIALS 23. Transcaspian Urial Ovis vignei arkal (Depending on locality aka Kopet Dagh, Ustyurt & Turkmen Urial) 24. Bukhara Urial Ovis vignei bocharensis 25. Afghan Urial Ovis vignei cycloceros 26. -

GREVY's ZEBRA Equus Grevyi Swahili Name

Porini Camps Mammal Guide By Rustom Framjee Preface This mammal guide provides some interesting facts about the mammals that are seen by guests staying at Porini Camps. In addition, there are many species of birds and reptiles which are listed separately from this guide. Many visitors are surprised at the wealth of wildlife and how close you can get to the animals without disturbing them. Because the camps operate on a low tourist density basis (one tent per 700 acres) the wildlife is not ‘crowded’ by many vehicles and you can see them in a natural state - hunting, socialising, playing, giving birth and fighting to defend their territories. Some are more difficult to see than others, and some can only be seen when you go on a night drive. All Porini camps are unfenced and located in game rich areas and you will see much wildlife even in and around the camps. The Maasai guides who accompany you on all game drives and walks are very well trained and qualified professional guides. They are passionate and enthusiastic about their land and its wildlife and really want to show you as much as they can. They have a wealth of knowledge and you are encouraged to ask them more about what you see. They know many of the animals individually and can tell you stories about them. If you are particularly interested in something, let them know and they will try to help you see it. While some facts and figures are from some of the references listed, the bulk of information in this guide has come from the knowledge of guides and camp staff. -

South Africa, 2017

WILDWINGS SOUTH AFRICA TOUR Wildwings Davis House MAMMALS AND BIRDS Lodge Causeway th th Bristol BS16 3JB 4 -14 SEPTEMBER 2017 LEADER – RICHARD WEBB +44 01179 658333 www.wildwings.co.uk Leopard INTRODUCTION After the success of the two previous Wildwings’ mammal tours to South Africa in 2016 we set off on the 2017 tour with high expectations and we were not to be disappointed. Despite longer than usual grass at Marrick which made spotlighting more difficult we still managed to find most of the species found on the two tours in 2016 plus a couple of real bonuses. The highlights among the 55 species of mammal seen included: A fantastic encounter with a pack of at least eight African Wild Dogs with seven three-month old puppies, plus another group of three females later the same day. A superb female Leopard on our first afternoon in Madikwe, with an awesome encounter with the same individual in the grounds of our lodge, including one of the clients finding her sitting on his balcony on our last evening! Our best views of Aardwolf to date in Marrick and prolonged views of Aardvark at the same location. Three Brown Hyaenas including one for over 30 minutes one afternoon. Two Black-footed Cats and no fewer than nine (recently-split) African Wildcats including a female with three kittens. 1 Two male Cheetahs and eight or nine Lions. Two Spotted-necked Otters feeding on a fish for over an hour at Warrenton. A superb Black Rhino and over 20 White Rhinos including a boisterous group of nine animals.