Language Ecology and Photographic Sound in the Mcworld

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Voicing on the Fringe: Towards an Analysis of ‘Quirkyʼ Phonology in Ju and Beyond

Voicing on the fringe: towards an analysis of ‘quirkyʼ phonology in Ju and beyond Lee J. Pratchett Abstract The binary voice contrast is a productive feature of the sound systems of Khoisan languages but is especially pervasive in Ju (Kx’a) and Taa (Tuu) in which it yields phonologically contrastive segments with phonetically complex gestures like click clusters. This paper investigates further the stability of these ‘quirky’ segments in the Ju language complex in light of new data from under-documented varieties spoken in Botswana that demonstrate an almost systematic devoicing of such segments, pointing to a sound change in progress in varieties that one might least expect. After outlining a multi-causal explanation of this phenomenon, the investigation shifts to a diachronic enquiry. In the spirit of Anthony Traill (2001), using the most recent knowledge on Khoisan languages, this paper seeks to unveil more on language history in the Kalahari Basin Area from these typologically and areally unique sounds. Keywords: Khoisan, historical linguistics, phonology, Ju, typology (AFRICaNa LINGUISTICa 24 (2018 100 Introduction A phonological voice distinction is common to more than two thirds of the world’s languages: whilst largely ubiquitous in African languages, a voice contrast is almost completely absent in the languages of Australia (Maddison 2013). The particularly pervasive voice dimension in Khoisan1 languages is especially interesting for two reasons. Firstly, the feature is productive even with articulatory complex combinations of clicks and other ejective consonants, gestures that, from a typological perspective, are incompatible with the realisation of voicing. Secondly, these phonological contrasts are robustly found in only two unrelated languages, Taa (Tuu) and Ju (Kx’a) (for a classification see Güldemann 2014). -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographicaily in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMI* GROUNDING JUl’HOANSI ROOT PHONOTACTICS: THE PHONETICS OF THE GUTTURAL OCP AND OTHER ACOUSTIC MODULATIONS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Amanda Miller-Ockhuizen, M.A. The Ohio State University 2001 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Mary. -

Khoisan’ Sibling Terminologies in Historical Perspective: a Combined Anthropological, Linguistic and Phylogenetic Comparative Approach

Boden, G., Güldemann, T., & Jordan, F. M. (2014). ‘Khoisan’ sibling terminologies in historical perspective: A combined anthropological, linguistic and phylogenetic comparative approach. In T. Güldemann, & A-M. Fehn (Eds.), Beyond 'Khoisan': Historical relations in the Kalahari Basin (pp. 67-100). (Current Issues in Linguistic Theory; Vol. 330). John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1075/cilt.330.03bod Peer reviewed version Link to published version (if available): 10.1075/cilt.330.03bod Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the author accepted manuscript (AAM). The final published version (version of record) is available online via John Benjamins at https://benjamins.com/catalog/cilt.330.03bod . Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ ‘Khoisan’ sibling terminologies in historical perspective: a combined anthropological, linguistic and phylogenetic comparative approach1 Gertrud Boden, Tom Güldemann & Fiona Jordan 1. Introduction In this paper we combine regional anthropological comparison, historical linguistics and phylogenetic comparative methodology (PCM) in addressing the historical relationships between the languages of the three South African ʻKhoisanʼ2 families, Kxʼa, Tuu and Khoe- Kwadi (see Güldemann, introduction, this volume). Since the data on extinct Kwadi are insufficient, this language had to be excluded, so that we will hereafter only refer to Khoe. Generally, the demonstrable linguistic relationships within Kxʼa (Heine & Honken 2010), Tuu (Güldemann 2005), and Khoe (Vossen 1997) imply original family-specific sibling terminologies with relevant lexemes as part of the proto-languages used within a social culture of the proto- societies (cf. -

An Inclusive Linguistic Framework for Botswana: Reconciling the State and Perceived Marginalized Communities

Journal of Information, Information Technology, and Organizations Volume 5, 2010 An Inclusive Linguistic Framework for Botswana: Reconciling the State and Perceived Marginalized Communities K. C. Monaka and S. M. Mutula University of Botswana, Botswana [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract A people’s language and increasingly information communication technologies (ICTs) have emerged as powerful forces in enhancing political and socio-economic development. In Botswana there are several ethnic groups with diverse linguistic dialects. Each of the ethnic groups desires its dialect to be recognized by the state as official or national languages - integrated in education, media, and governance. The government recognizes only Setswana as the officialdom language and perceives agitation for multiple language use in officialdom as divisive and a threat to the long standing political and economic stability of the nation. This paper sought to examine Botswana’s perceived marginalized linguistic dialects by the state and proposes a linguistic framework for Botswana incorporating institutional and ICT aspects, which would appeal to both government and the ethnic groups concerned. The proposed linguistic framework for Botswana is applied as the methodological tool to examine the exclusion of the minority languages from the officialdom. The findings suggest that several ethnic groups in Bot- swana perceive their linguistic dialects as marginalised by the state. They seek the support of re- gional advocacy groups to help them promote their language values and culture, and they employ ICT to achieve their aims. However, the groups have not explored the existing international, re- gional, and national institutional frameworks to address their linguistic plight. -

Handout Linguistic Substrate in Bantu

Linguistic influence from Khoisan in Bantu “Speaking (of) Khoisan”: a symposium reviewing southern African prehistory. Hilde Gunnink - Ghent University - [email protected] Koen Bostoen - Ghent University - [email protected] 0.0.0. ContactContact----inducedinduced changes 1. Borrowing also called copying, recipient language agentivity involves (some) multilingualism, no language shift affects the lexicon, in case of superficial contact, and the grammar, in case of more extensive contact transfer of forms, not patterns 2. Interference through shift also called substrate, imposition, source language agentivity involves multilingualism and language shift affects mainly phonology and syntax transfer of patterns, not forms (Thomason and Kaufman 1988; Van Coetsem 1988; 2000; Winford 2003; 2007; 2013, among others) 1.1.1. Evidence of borrowing from Khoisan in Bantu lexical borrowing • loanwords in Nguni and Sotho: o Zulu (Bantu, Nguni) ú-ḿ-qala ‘neck’ Xhosa (Bantu, Nguni) ú-ḿ-qala ‘throat’ cf. Nama (Khoekhoe) !ara-b ‘throat, gullet’ (Louw 1979: 14) o Xhosa/Zulu (Bantu, Nguni) i-dúbe ‘zebra’ cf. Nama (Khoekhoe) doe-b ‘mountain zebra (Louw 1979: 16) • loanwords in Yeyi (Bantu): Yeyi βù-|óá ‘red’ cf. Buga (Kalahari Khoe) |óá ‘red, brown’ Shua (Kalahari Khoe) |oa (Sommer and Voßen 1992: 25) 1 o loanwords in Manyo, Mbukushu, Kwangali (Bantu, Kavango), Fwe (Bantu, Bantu Botatwe), Yeyi (Bantu): Kwangali n|amúse ‘poor person’ cf. Ju|’hoan (Kx’a, Ju) n!àmm ‘poor person’ Manyo li-|wà ‘shallow water’ cf. Central !Xuun (Kx’a, Ju) !wa ‘vlei’ sáű ‘shallow place in water’ North-western !Xuun (Kx’a, Ju) cāú ‘shallow place in water’ (Gunnink et al. submitted) o loanwords in Herero (Bantu, South-West-Bantu): Herero o-tji-kaiva ‘das Tuch’ cf. -

Title Ambivalence Regarding Linguistic and Cultural Choices

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository Ambivalence Regarding Linguistic and Cultural Choices Title among Minority Language Speakers: A Case Study of the Khoesan Youth of Botswana Author(s) Gabanamotse-Mogara, Budzani; Batibo, Herman Michael Citation African Study Monographs (2016), 37(3): 103-115 Issue Date 2016-09 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/216688 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study Monographs, 37 (3): 103–115, September 2016 103 AMBIVALENCE REGARDING LINGUISTIC AND CULTURAL CHOICES AMONG MINORITY LANGUAGE SPEAKERS: A CASE STUDY OF THE KHOESAN YOUTH OF BOTSWANA Budzani Gabanamotse-Mogara Department of African Languages and Literature,University of Botswana Herman Michael Batibo Department of African Languages and Literature, University of Botswana ABSTRACT Due to their small numbers and historical domination by others, the Khoesan groups in the southern African region are among the most marginalized and endangered com- munities in Africa (Batibo, 1998; Chebanne & Nthapelelang, 2000; Smieja, 2003). This situa- tion has also led to their linguistic and cultural domination and an associated dilemma: on the one hand, the speakers of these minority languages wish to use and safeguard their linguistic and cultural heritage and identity; on the other hand, they desire to use other languages to en- able wider communication and socioeconomic advancement. This study examined this dilem- ma among Khoesan youth in three villages in the Central Kalahari and Ghanzi areas of western Botswana. The primary aim of the study was to determine the extent to which ambivalence re- garding linguistic and cultural options has affected the use of, attitudes toward, and attachment to languages and identities. -

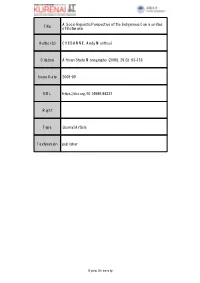

A Sociolinguistic Perspective of the Indigenous Communities Title of Botswana

A Sociolinguistic Perspective of the Indigenous Communities Title of Botswana Author(s) CHEBANNE, Andy Monthusi Citation African Study Monographs (2008), 29(3): 93-118 Issue Date 2008-09 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/66231 Right Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study Monographs, 29(3): 93-118, September 2008 93 A SOCIOLINGUISTIC PERSPECTIVE OF THE INDIGENOUS COMMUNITIES OF BOTSWANA Andy Monthusi CHEBANNE Faculty of Humanities, University of Botswana Visiting Fellow of the Graduate School of Asian and African Area Studies, Kyoto University, April – July, 2007 ABSTRACT The indigenous communities of Botswana discussed in this paper are gener- ally referred to as the Khoisan (Khoesan). While there are debates on the common origins of Khoisan communities, the existence of at least fi ve language families suggests a separate evolution that resulted in major grammatical and lexical differences between them. Due to historical confl icts with neighboring groups, they have been pushed far into the most inhos- pitable areas of the regions where they presently live. The most signifi cant victimization of Khoisan groups by the linguistic majority has been the systematic neglect of their languages and cultures. In fact, social and development programs have attempted to assimilate them into so-called majority ethnic groups and into modernity, and their languages have been dif- fi cult to conserve in contact situations. This paper provides an overview of these indigenous communities of Botswana and contributes to ongoing research of the region. I discuss rea- sons for the communities’ vulnerability by examining their demography, current localities, and language vitality. I also analyze some adverse effects of development and the danger the Khoisan face due to negative social and political attitudes, and formulate critical areas of in- tervention for the preservation of these indigenous languages. -

REVERSING ATTITUDES AS a KEY to LANGUAGE PRESERVATION and SAFEGUARDING in AFRICA Herman M

REVERSING ATTITUDES AS A KEY TO LANGUAGE PRESERVATION AND SAFEGUARDING IN AFRICA Herman M. Batibo University of Botswana 1. Introduction 1.1 Africa is not only the continent with the highest concentration of languages in the world, but also the area with the highest number of endangered languages (Grenoble and Whaley, 1998). 1.2 According to Batibo (2005:155), at least 74.8 of the African languages are either moderately or severely endangered and 9.4% are extinct or nearly extinct, as shown in Table 1 below: Table 1: The Position of Language endangered in Africa (After Batibo, 2005:155) Category of Language No. of language % of Category 1 Relatively safe 336 15.8% 2 Moderately endangered 1,287 60.4% 3 Severely endangered 308 14.4% 4 Extinct or nearly extinct 201 9.4% Total 2,132 100% 1.3 In recent years, the degree of endangerment has accelerated due to the increased prestige and dominance of the indigenous languages of wider communication, which have been accorded the status of national or official languages or used as lingua franca. This has resulted in the marginalization and low prestige of the minority languages. Consequently, many minority language speakers have developed negative attitudes towards their languages, resulting in limited intergenerational transmission. 1.4 In fact, the problem has been compounded in those African countries which have embarked on the process of technicalization and modernization of their major indigenous languages. These have indirectly become agents of globalization, attracting Western-based lifestyles at the expense of the rich traditional knowledge and skills embodied in the minority languages. -

LASU, Volume 4, No

1 LASU, Volume 4, No. 1, June 2013 LASU Journal of the Linguistics Associationof Southern African DevelopmentCommunity [SADC] Universities Volume 4, Issue No. 1, June 2013 [] [ISSN 1681 - 2794] I LASU, Volume 4, No. 1, June 2013 LASU, Volume 4, No. 1, June 2013 Journal of the Linguistics Association of Southern African Development Community [SADC] Universities Edited, published and distributed by the Linguistics Association of SADC Universities Editorial Board Profesor S.T.M. Lukusa: Editor-in-Chief Professor Al Mtenje: University of Malawi Professor T. Chisanga: University of Transkei Professor G. Kamwendo: University of Botswana Professor A.M. Chebanne: University of Botswana Dr. Femi Dele Akindele: University of Botswana Editorial Advisers Professor S. Matsinhe, University of South Africa, South Africa Professor H.M. Batibo, University of Botswana, Botswana Professor M.M. Machobane, National University of Lesotho, Lesotho Professor H. Chimhundu, University of Zimbabwe Professor A. Ngunga: Eduardo Mondlane University, Mozambique Enquiries about membership should be addressed to Dr Mildred Nkolola Wakumelo, LASU General Secretary, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, DEPARTMENT OF Literature & Languages, University of Zambia, E-mail [email protected] / [email protected] Further enquiries about the journal should be addressed to the Editor-in-Chief: Professor Stephen T.M. LUKUSA, Dept. of African Languages and Literature University of Botswana, P/Bag UB 00703, Gaborone, Botswana. Phone: +267 3552652 (Work); +267 71863289; e-mail: [email protected] II LASU, Volume 4, No. 1, June 2013 LASU Journal of the Linguistics Association for Southern African Development Community [SADC] Universities Instructions to Contributors The Linguistics Association for SADC Universities was established on November 26, 1984 at Chancellor College, University of Malawi by the representatives from SADC universities. -

From a Linguistic Perspective Tom Güldemann

lANGUAGES AND lITERATURES University of Leipzig Papers on Africa No.29 Clicks, genetics, and "proto world" from a linguistic perspective Tom Güldemann Leipzig 2007 University of Leipzig Papers on Africa Languages and Literatures Series No. 29 Clicks, genetics, and "proto-world" from a linguistic perspective Tom Güldemann Leipzig, 2007 ISBN 3-935999-55-0 Knight et al. (2003) have argued, largely from a genetic perspective, that clicks "may be more than 40.000 years old" (p.470) and thus "are an ancient element of human language" (p.471). This has nourished the hypothesis, expressed especially in popular science, that clicks were a feature of the ancestral mother tongue. The claim by Knight et al. (2003) is based on the observation that two populations in Africa speaking languages with click phonemes, namely Hadza in eastern Africa and Jul'hoan in southern Africa, are maximally distinct in genetic terms: both Y chromosome and mtDNA data suggest that the two "are separated by genetic distance as great [as] or greater than that between any other pair of African populations" (p.464). It is also claimed that the only explanation for the presence of clicks in the two groups is inheritance from an early common ancestor language, hence the alleged, very great age of clicks in general. other explanations for the clicks of Hadza and Jul'hoan, in particular independent development and language contact, are explicitly excluded by the authors. This paper seeks to demonstrate on the basis of purely linguistic evidence that this view cannot be accepted: both independent innovation and contact-induced transmission of clicks are attested. -

THE REVITALISATION of ETHNIC MINORITY LANGUAGES in ZIMBABWE: the CASE of the TONGA LANGUAGE by Submitted in Accordance With

THE REVITALISATION OF ETHNIC MINORITY LANGUAGES IN ZIMBABWE: THE CASE OF THE TONGA LANGUAGE by ISAAC MUMPANDE Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the subject SOCIOLINGUISTICS at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: PROF L. A. BARNES FEBRUARY 2020 DECLARATION Student Number: 61101273 I declare that Revitalisation of ethnic minority languages in Zimbabwe. The case of the Tonga language is my own work. All the sources that have been used and quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. __________________ Isaac Mumpande Date: 03 February 2020 ii ABSTRACT This dissertation investigates the revitalisation of Tonga, an endangered minority language in Zimbabwe. It seeks to establish why the Tonga people embarked on the revitalisation of their language, the strategies they used, the challenges they encountered and how they managed them. The Human Needs Theory propounded by Burton (1990) and Yamamoto’s (1998) Nine Factors Language Revitalisation Model formed the theoretical framework within which the data were analysed. This case-study identified various socio-cultural and historical factors that influenced the revitalisation of the Tonga language. Despite the socio-economic and political challenges from both within and outside the Tonga community, the Tonga revitalisation initiative was to a large extent a success, thanks to the speech community’s positive attitude and ownership of the language revitalisation process. It not only restored the use of Tonga in the home domain but also extended the language function into the domains of education, the media, and religion. Keywords Broad-focused language revitalisation models, Language ecology, Language endangerment, Language shift, Language revitalisation, Narrow-focused language revitalisation models, Tonga. -

Hessel Visser. Naro Dictionary: Naro–English, English–Naro

Resensies / Reviews 451 Hessel Visser. Naro Dictionary: Naro–English, English–Naro. Fourth edi- tion. 2001, viii + 240 pp. ISBN 99912-938-5-x. D'kar: Kuru Development Trust. Although this dictionary was not published by a well-established publishing house, its quality and usefulness rival those of seasoned publishers in the field of Khoesan studies, such as the dictionaries by Dickens (1994), Traill (1994) and Haacke (2002). This fourth edition of Visser's Naro Dictionary is a medium-sized dictionary of 240 pages, including 16 pages of appendices. The work is the result of more than 10 years of lexical compilation which resulted in several editions of the dictionary, each of which was an expanded version of the earlier one. Thus, from a miniature version, it has grown into a sizeable high-quality work, in spite of the compiler's modest observation in his introduction that it is a mere "working document" and that it is still a "preliminary publication". The dictionary begins with initial information for the users, such as the status of the present dictionary in relation to the earlier versions, the structure of the entire dictionary, the representation of the various sounds and the mark- ing of the prosodic features such as tone, nasalization and vowel depression. According to the compiler, the work on the dictionary was part of a broader project, the Naro Language Project, which included the preparation of primers, literacy materials, magazines, a Bible translation and other linguistic docu- ments. The dictionary itself is divided into two main parts. The Naro–English part has about 5 500 entries, arranged in alphabetical order.