The Destruction of the Medieval Chinese Aristocracy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

002170196E1c16a28b910f.Pdf

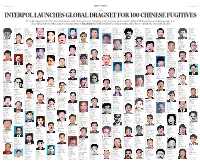

6 THURSDAY, APRIL 23, 2015 DOCUMENT CHINA DAILY 7 JUSTICE INTERPOL LAUNCHES GLOBAL DRAGNET FOR 100 CHINESE FUGITIVES It’s called Operation Sky Net. Amid the nation’s intensifying antigraft campaign, arrest warrants were issued by Interpol China for former State employees and others suspected of a wide range of corrupt practices. China Daily was authorized by the Chinese justice authorities to publish the information below. Language spoken: Liu Xu Charges: Place of birth: Anhui property and goods Language spoken: Zeng Ziheng He Jian Qiu Gengmin Wang Qingwei Wang Linjuan Chinese, English Sex: Male Embezzlement Language spoken: of another party by Chinese Sex: Male Sex: Male Sex: Male Sex: Male Sex: Female Charges: Date of birth: Chinese, English fraud Charges: Date of birth: Date of birth: Date of birth: Date of birth: Date of birth: Accepting bribes 07/02/1984 Charges: Embezzlement Embezzlement 15/07/1971 14/11/1965 15/05/1962 03/01/1972 17/07/1980 Place of birth: Beijing Place of birth: Henan Language spoken: Place of birth: Place of birth: Place of birth: Language spoken: Language spoken: Chinese Zhejiang Jinan, Shandong Jilin Chinese, English Chinese Charges: Graft Language spoken: Language spoken: Language spoken: Charges: Corruption Charges: Chinese Chinese, English Chinese Embezzlement Charges: Contract Charges: Commits Charges: fraud, and flight of fraud by means of a Misappropriation of Yang Xiuzhu 25/11/1945 Place of birth: Chinese Zhang Liping capital contribution Chu Shilin letter of credit Dai Xuemin public funds Sex: Female -

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907)

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 BuYun Chen All rights reserved ABSTRACT Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen During the Tang dynasty, an increased capacity for change created a new value system predicated on the accumulation of wealth and the obsolescence of things that is best understood as fashion. Increased wealth among Tang elites was paralleled by a greater investment in clothes, which imbued clothes with new meaning. Intellectuals, who viewed heightened commercial activity and social mobility as symptomatic of an unstable society, found such profound changes in the vestimentary landscape unsettling. For them, a range of troubling developments, including crisis in the central government, deep suspicion of the newly empowered military and professional class, and anxiety about waste and obsolescence were all subsumed under the trope of fashionable dressing. The clamor of these intellectuals about the widespread desire to be “current” reveals the significant space fashion inhabited in the empire – a space that was repeatedly gendered female. This dissertation considers fashion as a system of social practices that is governed by material relations – a system that is also embroiled in the politics of the gendered self and the body. I demonstrate that this notion of fashion is the best way to understand the process through which competition for status and self-identification among elites gradually broke away from the imperial court and its system of official ranks. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Tang China and the Collapse of the Uighur Empire a Documentary History by Michael R

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Tang China And The Collapse Of The Uighur Empire A Documentary History by Michael R. Drompp Tang China And The Collapse Of The Uighur Empire: A Documentary History by Michael R. Drompp. Our systems have detected unusual traffic activity from your network. Please complete this reCAPTCHA to demonstrate that it's you making the requests and not a robot. If you are having trouble seeing or completing this challenge, this page may help. If you continue to experience issues, you can contact JSTOR support. Block Reference: #640642a0-d013-11eb-8743-0da9024df238 VID: #(null) IP: 116.202.236.252 Date and time: Fri, 18 Jun 2021 08:58:46 GMT. Tang China And The Collapse Of The Uighur Empire: A Documentary History by Michael R. Drompp. Our systems have detected unusual traffic activity from your network. Please complete this reCAPTCHA to demonstrate that it's you making the requests and not a robot. If you are having trouble seeing or completing this challenge, this page may help. If you continue to experience issues, you can contact JSTOR support. Block Reference: #6411db60-d013-11eb-acd7-7bc3fb1b8127 VID: #(null) IP: 116.202.236.252 Date and time: Fri, 18 Jun 2021 08:58:46 GMT. The Destruction of the Medieval Chinese Aristocracy. In 845, Li Deyu 李德裕 (787–850), arguably the most powerful man of the realm at that time and scion of one of the great aristocratic clans of medieval China, submitted a ‘Stele Inscription for Commemorating the Sagely Deeds in Youzhou, with preface’ (‘Youzhou ji shenggong beiming bing xu’ 幽州紀聖功碑銘并序) to Emperor Li Yan 李炎 (r. -

Adaptive Fuzzy Pid Controller's Application in Constant Pressure Water Supply System

2010 2nd International Conference on Information Science and Engineering (ICISE 2010) Hangzhou, China 4-6 December 2010 Pages 1-774 IEEE Catalog Number: CFP1076H-PRT ISBN: 978-1-4244-7616-9 1 / 10 TABLE OF CONTENTS ADAPTIVE FUZZY PID CONTROLLER'S APPLICATION IN CONSTANT PRESSURE WATER SUPPLY SYSTEM..............................................................................................................................................................................................................1 Xiao Zhi-Huai, Cao Yu ZengBing APPLICATION OF OPC INTERFACE TECHNOLOGY IN SHEARER REMOTE MONITORING SYSTEM ...............................5 Ke Niu, Zhongbin Wang, Jun Liu, Wenchuan Zhu PASSIVITY-BASED CONTROL STRATEGIES OF DOUBLY FED INDUCTION WIND POWER GENERATOR SYSTEMS.................................................................................................................................................................................9 Qian Ping, Xu Bing EXECUTIVE CONTROL OF MULTI-CHANNEL OPERATION IN SEISMIC DATA PROCESSING SYSTEM..........................14 Li Tao, Hu Guangmin, Zhao Taiyin, Li Lei URBAN VEGETATION COVERAGE INFORMATION EXTRACTION BASED ON IMPROVED LINEAR SPECTRAL MIXTURE MODE.....................................................................................................................................................................18 GUO Zhi-qiang, PENG Dao-li, WU Jian, GUO Zhi-qiang ECOLOGICAL RISKS ASSESSMENTS OF HEAVY METAL CONTAMINATIONS IN THE YANCHENG RED-CROWN CRANE NATIONAL NATURE RESERVE BY SUPPORT -

A Data Compression Algorithm Based on Adaptive Huffman Code for Wireless Sensor Networks

2011 Fourth International Conference on Intelligent Computation Technology and Automation (ICICTA 2011) Shenzhen, China 28 – 29 March 2011 Volume 1 Pages 1-618 IEEE Catalog Number: CFP1188E-PRT ISBN: 978-1-61284-289-9 1/4 2011 Fourth International Conference on Intelligent Computation Technology and Automation ICICTA 2011 Table of Contents Volume - 1 Preface - Volume 1.....................................................................................................................................................xxv Conference Committees - Volume 1.......................................................................................................................xxvi Reviewers - Volume 1.............................................................................................................................................xxviii Session 1: Advanced Comptation Theory and Applications A Data Compression Algorithm Based on Adaptive Huffman Code for Wireless Sensor Networks .............................................................................................................................................................3 Mo Yuanbin, Qiu Yubing, Liu Jizhong, and Ling Yanxia A Genetic Algorithm for Solving Weak Nonlinear Bilevel Programming Problems ....................................................7 Yulan Xiao and Hecheng Li A Layering Learning Routing Algorithm of WSNs Based on ADS Approach ............................................................10 Wang Zhaoqing and Zhong Sheng A Load Distribution Optimization among -

Commissioner Li and Prefect Huang: Sino-Vietnamese Frontier Trade Networks and Political Alliances in the Southern Song

sino-vietnamese trade and alliances james a. anderson Commissioner Li and Prefect Huang: Sino-Vietnamese Frontier Trade Networks and Political Alliances in the Southern Song INTRODUCTION rom the 900s to the 1200s, political loyalties in the upland areas F along the Sino-Vietnamese frontier were a complicated matter. The Dai Viet 大越 kingdom, while adopting elements of the imperial Chinese system of frontier administration, ruled at less of a distance from their upland subjects. Marriage alliances between the local elite and the Ly 李 (1009–1225) and Tran 陳 (1225–1400) royal dynasties helped bind these upland areas more closely to the central court. By contrast, both the Northern and Southern Song courts (960–1279) were preoccupied with their northern frontiers, investing most of the courts’ resources in that region, while relying on a small contingent of officials situated in Yongzhou 邕州 (modern-day Nanning) to pursue imperial aims along the southern frontier. The behavior of the frontier elite was also closely linked to changes in the flow of trade across the Sino-Vietnamese bor- derlands, and the impact of changing patterns in trade will play a role in this study. Broadly speaking, this paper focuses on a triangular re- gion, the base of which stretches from the Song port of Qinzhou 欽州 to the inland frontier region at Longzhou 龍州 (Guangxi). (See the maps provided in the Introduction to this volume.) These two points at either end of the base in this territorial triangle meet at Yongzhou, which was the center of early-Song administration for the Guangnan West circuit (Guangnan xilu 廣南西路). -

Recent Articles from the China Journal of System Engineering Prepared

Recent Articles from the China Journal of System Engineering Prepared by the University of Washington Quantum System Engineering (QSE) Group.1 Bibliography [1] Mu A-Hua, Zhou Shao-Lei, and Yu Xiao-Li. Research on fast self-adaptive genetic algorithm and its simulation. Journal of System Simulation, 16(1):122 – 5, 2004. [2] Guan Ai-Jie, Yu Da-Tai, Wang Yun-Ji, An Yue-Sheng, and Lan Rong-Qin. Simulation of recon-sat reconing process and evaluation of reconing effect. Journal of System Simulation, 16(10):2261 – 3, 2004. [3] Hao Ai-Min, Pang Guo-Feng, and Ji Yu-Chun. Study and implementation for fidelity of air roaming system above the virtual mount qomolangma. Journal of System Simulation, 12(4):356 – 9, 2000. [4] Sui Ai-Na, Wu Wei, and Zhao Qin-Ping. The analysis of the theory and technology on virtual assembly and virtual prototype. Journal of System Simulation, 12(4):386 – 8, 2000. [5] Xu An, Fan Xiu-Min, Hong Xin, Cheng Jian, and Huang Wei-Dong. Research and development on interactive simulation system for astronauts walking in the outer space. Journal of System Simulation, 16(9):1953 – 6, Sept. 2004. [6] Zhang An and Zhang Yao-Zhong. Study on effectiveness top analysis of group air-to-ground aviation weapon system. Journal of System Simulation, 14(9):1225 – 8, Sept. 2002. [7] Zhang An, He Sheng-Qiang, and Lv Ming-Qiang. Modeling simulation of group air-to-ground attack-defense confrontation system. Journal of System Simulation, 16(6):1245 – 8, 2004. [8] Wu An-Bo, Wang Jian-Hua, Geng Ying-San, and Wang Xiao-Feng. -

The Eurasian Transformation of the 10Th to 13Th Centuries: the View from Song China, 906-1279

Haverford College Haverford Scholarship Faculty Publications History 2004 The Eurasian Transformation of the 10th to 13th centuries: The View from Song China, 906-1279 Paul Jakov Smith Haverford College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.haverford.edu/history_facpubs Repository Citation Smith, Paul Jakov. “The Eurasian Transformation of the 10th to 13th centuries: The View from the Song.” In Johann Arneson and Bjorn Wittrock, eds., “Eurasian transformations, tenth to thirteenth centuries: Crystallizations, divergences, renaissances,” a special edition of the journal Medieval Encounters (December 2004). This Journal Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at Haverford Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Haverford Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Medieval 10,1-3_f12_279-308 11/4/04 2:47 PM Page 279 EURASIAN TRANSFORMATIONS OF THE TENTH TO THIRTEENTH CENTURIES: THE VIEW FROM SONG CHINA, 960-1279 PAUL JAKOV SMITH ABSTRACT This essay addresses the nature of the medieval transformation of Eurasia from the perspective of China during the Song dynasty (960-1279). Out of the many facets of the wholesale metamorphosis of Chinese society that characterized this era, I focus on the development of an increasingly bureaucratic and autocratic state, the emergence of a semi-autonomous local elite, and the impact on both trends of the rise of the great steppe empires that encircled and, under the Mongols ultimately extinguished the Song. The rapid evolution of Inner Asian state formation in the tenth through the thirteenth centuries not only swayed the development of the Chinese state, by putting questions of war and peace at the forefront of the court’s attention; it also influenced the evolution of China’s socio-political elite, by shap- ing the context within which elite families forged their sense of coorporate identity and calibrated their commitment to the court. -

The Road to Literary Culture: Revisiting the Jurchen Language Examination System*

T’OUNG PAO 130 T’oung PaoXin 101-1-3 Wen (2015) 130-167 www.brill.com/tpao The Road to Literary Culture: Revisiting the Jurchen Language Examination System* Xin Wen (Harvard University) Abstract This essay contextualizes the unique institution of the Jurchen language examination system in the creation of a new literary culture in the Jin dynasty (1115–1234). Unlike the civil examinations in Chinese, which rested on a well-established classical canon, the Jurchen language examinations developed in close connection with the establishment of a Jurchen school system and the formation of a literary canon in the Jurchen language and scripts. In addition to being an official selection mechanism, the Jurchen examinations were more importantly part of a literary endeavor toward a cultural ideal. Through complementing transmitted Chinese sources with epigraphic sources in Jurchen, this essay questions the conventional view of this institution as a “Jurchenization” measure, and proposes that what the Jurchen emperors and officials envisioned was a road leading not to Jurchenization, but to a distinctively hybrid literary culture. Résumé Cet article replace l’institution unique des examens en langue Jurchen dans le contexte de la création d’une nouvelle culture littéraire sous la dynastie des Jin (1115–1234). Contrairement aux examens civils en chinois, qui s’appuyaient sur un canon classique bien établi, les examens en Jurchen se sont développés en rapport étroit avec la mise en place d’un système d’écoles Jurchen et avec la formation d’un canon littéraire en langue et en écriture Jurchen. En plus de servir à la sélection des fonctionnaires, et de façon plus importante, les examens en Jurchen s’inscrivaient * This article originated from Professor Peter Bol’s seminar at Harvard University. -

A Visualization Quality Evaluation Method for Multiple Sequence Alignments

2011 5th International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedical Engineering (iCBBE 2011) Wuhan, China 10 - 12 May 2011 Pages 1 - 867 IEEE Catalog Number: CFP1129C-PRT ISBN: 978-1-4244-5088-6 1/7 TABLE OF CONTENTS ALGORITHMS, MODELS, SOFTWARE AND TOOLS IN BIOINFORMATICS: A Visualization Quality Evaluation Method for Multiple Sequence Alignments ............................................................1 Hongbin Lee, Bo Wang, Xiaoming Wu, Yonggang Liu, Wei Gao, Huili Li, Xu Wang, Feng He A New Promoter Recognition Method Based On Features Optimal Selection.................................................................5 Lan Tao, Huakui Chen, Yanmeng Xu, Zexuan Zhu A Center Closeness Algorithm For The Analyses Of Gene Expression Data ...................................................................9 Huakun Wang, Lixin Feng, Zhou Ying, Zhang Xu, Zhenzhen Wang A Novel Method For Lysine Acetylation Sites Prediction ................................................................................................ 11 Yongchun Gao, Wei Chen Weighted Maximum Margin Criterion Method: Application To Proteomic Peptide Profile ....................................... 15 Xiao Li Yang, Qiong He, Si Ya Yang, Li Liu Ectopic Expression Of Tim-3 Induces Tumor-Specific Antitumor Immunity................................................................ 19 Osama A. O. Elhag, Xiaojing Hu, Weiying Zhang, Li Xiong, Yongze Yuan, Lingfeng Deng, Deli Liu, Yingle Liu, Hui Geng Small-World Network Properties Of Protein Complexes: Node Centrality And Community Structure -

Download PDF ^ Articles on Tang Dynasty Jiedushi of Shannan

K981YROKONYQ » Doc » Articles On Tang Dynasty Jiedushi Of Shannan East Circuit, including: Yu Di,... Download PDF ARTICLES ON TANG DYNASTY JIEDUSHI OF SHANNAN EAST CIRCUIT, INCLUDING: YU DI, JIA DAN, LI LIN (PRINCE), PEI DU, LIANG CHONGYI, LI SU, YUAN ZI, LI FENGJI, LI YIJIAN, NIU SENGRU, LI CHENG To get Articles On Tang Dynasty Jiedushi Of Shannan East Circuit, including: Yu Di, Jia Dan, Li Lin (prince), Pei Du, Liang Chongyi, Li Su, Yuan Zi, Li Fengji, Li Yijian, Niu Sengru, Li Cheng eBook, please access the web link listed below and download the le or gain access to additional information which might be highly relevant to ARTICLES ON TANG DYNASTY JIEDUSHI OF SHANNAN EAST CIRCUIT, INCLUDING: YU DI, JIA DAN, LI LIN (PRINCE), PEI DU, LIANG CHONGYI, LI SU, YUAN ZI, LI FENGJI, LI YIJIAN, NIU SENGRU, LI CHENG book. Read PDF Articles On Tang Dynasty Jiedushi Of Shannan East Circuit, including: Yu Di, Jia Dan, Li Lin (prince), Pei Du, Liang Chongyi, Li Su, Yuan Zi, Li Fengji, Li Yijian, Niu Sengru, Li Cheng Authored by Books, Hephaestus Released at 2016 Filesize: 5.6 MB Reviews This publication is wonderful. It normally is not going to expense too much. Its been printed in an extremely straightforward way in fact it is merely following i finished reading this publication where actually transformed me, modify the way i really believe. -- Russell Adams DDS This publication is denitely not effortless to get going on looking at but really exciting to read through. It really is rally intriguing throgh looking at time period. -

While Rome Burns – the Battle of Yongqiu 756 CE 1Up Podcast Network

While Rome Burns – The Battle of Yongqiu 756 CE 1up Podcast Network In 8th century CE China, The An Lushan rebellion rose up in opposition to the wildly successful Tang dynasty. As the rebellion advanced from small rebellion to overwhelming opposing state, it seemed as if the Tang dynasty and the accompanying golden age, was over. But for some loyal soldiers of the Tang dynasty, losing hope and faith in their Emperor was an unacceptable position. Our story today is a story of brilliant tactics, loyalty, and just a bit of brashness. Our story is about The Battle of Yongqiu in 756 CE. Sit Back… relax… And let me tell you a story… While Rome Burns. The Tang dynasty rose to power in 618 CE. Emperor’s rose and fell over the years, but the general stability that the Tang established led to a golden age of art, literature and culture from China. This golden age reached its peak during the 44-year rule of the Emperor Xuanzong. Poets such as Du Fu, Li Bai produced their great works during this time, the trading of goods from China into the middle east became a huge industry, the government of China was staffed by members of a variety of political factions, and inflation in the Chinese economy was reduced. By all rights, the Tang dynasty looked to be on track for a long, healthy, and prosperous existence for decades and possibly centuries to come. But this prosperity was not shared by all throughout the Chinese empire and eventually the stirrings of discontent by those feeling exploited exploded into full on rebellion.