Walker, Howard K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vietnam January-August 1963

III. BEGINNING OF THE BUDDHIST CRISIS, MM 9-JUNE 16: INCIDENT IN HUE, THE FIVE BUDDHIST DEMANDS, USE OF TEAR GAS IN HUE, SELF- IMMOLAHON OF QUANG DUC, NEGOTIAl-IONS IN SAIGON TO RESOLVE THE CRISIS, AGREEMENT ON THE FIVE DEMANDS 112. Telegram From the Consulate at Hue to the Department of State’ Hue, May 9, 1963-3 p.m. 4. Buddha Birthday Celebration Hue May 8 erupted into large- scale demonstration at Hue Radio Station between 2000 hours local and 2330 hours. At 2245 hours estimated 3,000 crowd assembled and guarded by 8 armored cars, one Company CG, one Company minus ARVN, police armored cars and some carbines fired into air to disperse mob which apparently not unruly but perhaps deemed menacing by authorities. Grenade explosion on radio station porch killed four chil- dren, one woman, Other incidents, possibly some resulting from panic, claimed two more children plus one person age unknown killed. Total casualties for evening 8 killed, 4 wounded. ’ I Source: Department of State, Central Files, POL 25 S VIET. Secret; Operational Immediate. Received at 8:33 a.m. 2 At 7 p.m. the Embassy in Saigon sent a second report of the incident to Washing- ton, listing seven dead and seven injured. The Embassy noted that Vietnamese Govern- ment troops may have fired into the crowd, but most of the casualties resulted, the Embassy reported, from a bomb, a concussion grenade, or “from general melee”. The Embassy observed that although there had been no indication of Viet Cong activity in connection with the incident, the Viet Cong could be expected to exploit future demon- strations. -

Security Reform Beyond the Project on National Security Reform

United States Army War College Class of 2013 DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT: A Approved for Public Release Distribution is Unlimited This manuscript is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the U.S. Army War College Fellowship. The views expressed in this student academic research paper are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. Security Reform beyond the Project on National Security Reform by Author Appears Here when Entered on SF 298 Army COL Brian Mennes The U.S. Army War College is accredited by the Commission on Higher Education of the Middle States Association of Colleges and Schools, 3624 Market Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104, (215) 662-5606. The Commission on Higher Education is an institutional accrediting agency recognized by the U.S. Secretary of Education and the Council for Higher Education Accreditation. REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 The public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing the burden, to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. -

Chapter I Introduction

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A. Background Malaysia is a country which consists of various ethnic groups or multiethnic populations. From the various ethnic groups there are three ethnicities which have the biggest population in Malaysia; there are Melayu, Chinese, and Indian. Melayu is the biggest ethnic population, because this ethnic is the original ethnic which is the oldest inhabittant in Malaysia state territory compared to the other two ethnic groups. Malay ethnic and indigenous tribes of Malaysia are known as Bumiputera which refers to the indigenous population who has lived in this land since a long time ago. While the other two ethnic groups are the immigrants who come from China and India. Indian population is the descendant of Indian immigrant who come to Tanah Melayu (Malaysia) in the 11th century and during the British occupation. Meanwhile The Chinese population is the descendant of Chinese immigrants who came to Tanah Melayu (Malaysia) in the 15th and early 20th centuries as traders.1 Chinese and Indian come to Malaysia generally for trade or work in British colonial's company and plantation, then the descendants of Chinese and Indian immigrants become the Malaysian citizens today. According to the population census in 2012, Melayu is the first placed population with the percentage of 50.4%, while Chinese the second place population with the percentage 23.7% and 1 J. Cambria (2010, April). Overseas Chinese in Malaysia Chinatownology, Retrieved September 02, 2017, from http://www.chinatownology.com/overseas_chinese_malaysia.html i followed by Indians in third place with 7.1% from 29.17 million Malaysian total population. -

Togo and Mali 1959-1961

John Gunther Dean’s introductory comments to the 5 files on Togo and Mali and complete inventory of the individual folders [7 pages] donated to the National Archives of the USA [The Jimmy Carter Library in Atlanta, Georgia]. [1959 – 1961]. 1 Inventory and comments on J.G.Dean’s files on Opening U.S. diplomatic missions in West Africa after independence Togo and Mali 1959 – 1961 Introduction to the files entitled “Opening U.S. diplomatic missions in West Africa after independence: 1959 – 1961” In the year 1960 independence came to many parts of West Africa. It was an exciting time as colonies and trust territories received their independence. Perhaps Washington’s primary concern was that the newly independent countries would not turn to the Soviet Union or Communist China as models for development. Sekou Touré of Guinea had opted for that path. As a young Foreign Service Officer, John Gunther Dean participated in establishing an American presence in two countries acceding to independence: Togo and Mali. In order to fully understand what happened and who did what to whom, it is useful to read first J.G.D.’s Oral History on his experiences in West Africa. [Item 1 of this chapter] In Togo, J.G.D. not only opened the post, but was also asked to pinch hit as Diplomatic Advisor for the new President of Togo, Sylvanus Olympio. In Mali, J.G.D. was the first foreign representative and was helpful to Mali’s march toward modernization and democracy. More than 40 years later U.S. - Malian relations are still excellent. -

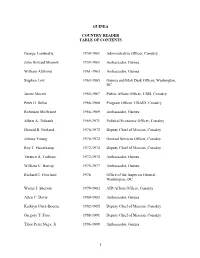

Table of Contents

GUINEA COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS George Lambrakis 1959-1961 Administrative Officer, Conakry John Howard Morrow 1959-1961 Ambassador, Guinea William Attwood 1961-1963 Ambassador, Guinea Stephen Low 1963-1965 Guinea and Mali Desk Officer, Washington, DC James Moceri 1965-1967 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Conakry Peter O. Sellar 1966-1968 Program Officer, USAID, Conakry Robinson McIlvaine 1966-1969 Ambassador, Guinea Albert A. Thibault 1969-1971 Political/Economic Officer, Conakry Donald R. Norland 1970-1972 Deputy Chief of Mission, Conakry Johnny Young 1970-1972 General Services Officer, Conakry Roy T. Haverkamp 1972-1974 Deputy Chief of Mission, Conakry Terence A. Todman 1972-1975 Ambassador, Guinea William C. Harrop 1975-1977 Ambassador, Guinea Richard C. Howland 1978 Office of the Inspector General, Washington, DC Walter J. Sherwin 1979-1982 AID Affairs Officer, Conakry Allen C. Davis 1980-1983 Ambassador, Guinea Kathryn Clark-Bourne 1982-1985 Deputy Chief of Mission, Conakry Gregory T. Frost 1988-1991 Deputy Chief of Mission, Conakry Tibor Peter Nagy, Jr. 1996-1999 Ambassador, Guinea 1 Joyce E. Leader 1999-2000 Ambassador, Guinea GEORGE LAMBRAKIS Administrative Officer Conakry (1959-1961) George Lambrakis was born in Illinois in 1931. After receiving his bachelor’s degree from Princeton University in 1952, he went on to earn his master’s degree from Johns Hopkins University in 1953 and his law degree from Tufts University in 1969. His career has included positions in Saigon, Pakse, Conakry, Munich, Tel Aviv, and Teheran. Mr. Lambrakis was interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy in June 2002. LAMBRAKIS: Bill Lewis was my immediate boss. And after two years in INR I was given my choice of three African assignments, I chose Conakry because it was a brand new post, and I spoke French. -

Abbreviations and Terms

1330_chfm.qxd 9/20/07 9:09 AM Page XIX 310-567/B428-S/11007 Abbreviations and Terms AF, Air Force AFB, Air Force Base AFSOUTH, Armed Forces South AHEPA, American-Hellenic Educational and Progressive Association AID, Agency for International Development AKEL, Anorthotikon Komma Ergazo Laou (Reform Party of the Working People) (Cyprus) AMB, Ambassador AMCITS, American citizens AMCONGEN, American Consul General AMCONSUL, American Consul AMEMBASSY, American Embassy ASW, antisubmarine warfare A/SYG, Assistant Secretary General C, Office of the Counselor, Department of State CA, circular airgram CCC, Commodity Credit Corporation CDI, Common Defense Installations CENTO, Central Treaty Organization Cherokee, special telegram channel CIA, Central Intelligence Agency CINC, Commander in Chief CINCEUR, Commander in Chief, U.S. Forces, Europe CINCLANT, Commander in Chief, Atlantic Command CINCSOUTH, Commander in Chief, U.S. Forces, Southern Europe CINCUSAFE, Commander in Chief, U.S. Air Force, Europe CINCUSAREUR, Commander in Chief, U.S. Army, Europe CINCUSNAVEUR, Commander in Chief, U.S. Navy, Europe CINCSTRIKE, Commander in Chief, Strike Command Col, Colonel COMSIXTHFLT, Commander, Sixth Fleet CONGEN, Consul General Controlled Dissem, controlled dissemination CONUS, continental United States CPA, Cypriot Provisional Authority CR, Continuing Resolution CSCE, Council on Security and Cooperation in Europe CYPOL, Cypriot Police CY, calendar year D, Deputy Secretary of State D/INR, Director, Bureau of Intelligence and Research, Department of State DA, -

The Foreign Service Journal, June 1947

g/,t AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE VOL 21. NO. 6 JOURNAL IN NEW YORK... “EL MOROCCO" is one spot sure to be visited by anyone eager to see the best in New York. Schenley Reserve Whiskey is one of the good things to be found there. for poimoissoiirK anywhere in flip world . OVERSEAS ...Wherever people of discriminating taste gather, Schenley is always in evidence. It is one of the fine things that are always in demand wherever the discerning meet. • Always ask for Schenley Reserve, the bright, light American Whiskey with a rich, mellow flavor that is superbly different. Enjoy it with soda, ginger ale, or water — use it in cocktails and other mixed drinks. Its excellence is a tradition. Schenley International Corpora¬ tion, Empire State Building, New York 1, N. Y., U. S. A. In the Smart World, it’s The world9* lamest selling SCHENLEY trhiskeif CONTENTS JUIVE 1947 Cover Picture: Change in Title: Using: an air-powered chisel, employees of the Public Bindings Administra¬ tion chip away the letters over the entrance of the War Department Building; on Virginia Ave. which has been taken over by the State Depart¬ ment. Photo courtesy Washington Post. For interior views see page 25. Foreign Service Changes 3 Promotions 5 Joint Observations and Recommendations of the 1947 Selection Boards 7 Impressions of the “Outside Man” on the Junior Foreign Service Selection Board for 1947.. 10 By G. W. Magalhaes French Reorganize Training for Government Service 1 1 By Franklin Roudybush Philippine Trainees Gain Field Experience 12 By Pablo A. Pena and Anastacio B. -

CHAPTER 3 CREATING a SECURITY OFFICE: Robert L

CHAPTER 3 CREATING A SECURITY OFFICE: Robert L. Bannerman and Cold War, 1945-1950 CHAPTER 3 8 CREATING A SECURITY OFFICE Robert L. Bannerman and Cold War, 1945-1950 After World War II, tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union gradually escalated into the Cold War. A global rivalry, the Cold War played out across the political, military, economic, and cultural relations between the world’s nation-states. Even though the two superpowers did not engage in direct military hostilities, several proxy wars occurred in the developing world, most notably in Korea and Vietnam. The U.S.- Soviet rivalry reinforced and elevated the Department of State’s concerns regarding diplomatic security. As a result, the Department created a formal office to devise, execute, and enforce diplomatic security practices. The Department of State’s Security Office was the creation of Robert L. Bannerman. It would be logical to assume that Bannerman’s efforts occurred within the Office of the Chief Special Agent (CSA) because Bannerman worked as a Special Agent in the CSA during the war; however, Bannerman actually left the CSA and formed a new office devoted to security. Department officials opted to create a new office rather than restructure the CSA because they believed that the CSA did not have the experience for “the approaching new concept of security” needed in the post-World War II era.1 The catalyst for hiring Bannerman to build the Security Office was the 1945Amerasia spy case. Soon other charges of espionage and disloyalty intensified the demand for an effective security program within the Department. -

Reframing Cultural Diplomacy: the Instrumentalization of Culture Under the Soft Power Theory

Reframing Cultural Diplomacy: The Instrumentalization of Culture under the Soft Power Theory By Mariano Martín Zamorano Abstract Although cultural diplomacy has grown in importance in recent years, there is no consensus on its definition. Cultural diplomacy is commonly framed in terms of soft power: the capacity of persuasion and attraction that allows the state to construct hegemony without using coercive methods. In this article, I offer a cri- tical analysis of this theory’s limitations. To shed light on this situation, I provide an historical analysis of cultural diplomacy. Based on this historical analysis and on an extensive desk research, I examine the dominant methodological and con- ceptual articulation of soft power in cultural diplomacy literature to clarify how the logical framework of soft power favors a specific and restrained conception of these policies, narrowing its understanding and legitimating its economic and political instrumentalization. Keywords: cultural diplomacy, soft power, instrumentalization, bran- ding, propaganda Zamorano, Mariano Martín: “Reframing Cultural Diplomacy: The Instrumentaliza- tion of Culture under the Soft Power Theory”, Culture Unbound, Volume 8, 2016: 166–186. Published by Linköping University Electronic Press: http://www.culture- unbound.ep.liu.se Culture Unbound Journal of Current Cultural Research Introduction In today´s globalized and highly interconnected world, cultural diplomacy is re- ceiving renewed attention. Social and economic changes as well as geopolitical transformations have led to a new relevance for international cultural policies. The impulse towards financial and technological globalization and post-Fordism economic changes (Jessop 2002; Brenner 2004) have given greater importance to cultural production and consumption in the so-called post-industrial society (Bell 1976; Morató 2012). -

The Foreign Service Journal, November 1953

NOVEMBER, 1953 To ALL coffee lovers they’re a promise of real cof¬ fee enjoyment...of that mellow, rich goodness that comes from superbly blended choice coffees brought to the peak of flavor by careful roasting. And this fresh-from-the-roaster goodness is sealed in...for each tin, each jar is vacuum-packed ... air and moisture are kept out... the flavor kept in! Wherever and whenever you want the finest for yourself and your guests ... remember that these wonderful blends are truly the coffees to serve. PRODUCTS OF GENERAL FOODS Export Division 250 Park Avenue, New York City, N. Y., U. S. A. 1 NOVEMBER, 1953 'A Gwwpem leek! Low and racy in design like a costly foreign sports car ! Thoroughly American in comfort! Down to earth in price ! No WONDER this low-swung new Studebaker with the European look is a sensational seller. People everywhere say it’s the most refreshingly dif¬ ferent, most strikingly original car they ever saw. Studebaker receives But your biggest thrill comes when you drive this Fashion Academy sleek Studebaker. It sparkles with zip and pep—and v/' V you never felt so safe and secure before in any car. \x Gold Medal At surprisingly small cost, you can own a brilliantly \x powered Studebaker Commander V-8—or a long, lux¬ vx V Noted New York school of urious Champion in the popular price field. NX NX fashion design names Studebaker Nine body styles — sedans, coupes, hard-tops — all vx NX outstanding in style gas economy team-mates of Studebaker Mobilgas Run NX stars. -

Business As Mission a Comprehensive Guide to Theory and Practice 1St Edition Download Free

BUSINESS AS MISSION A COMPREHENSIVE GUIDE TO THEORY AND PRACTICE 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE C Neal Johnson | 9780830838653 | | | | | Business As Mission: A Comprehensive Guide to Theory and Practice This section does not cite any sources. Have a question about this product? In times of peace, diplomacy was even conducted with non-Hellenistic rivals such as the Achaemenid Empire of Persia, through it was ultimately conquered by Alexander the Great of Macedon. All these neighbors lacked a key resource that Byzantium had taken over from Rome, namely a formalized legal structure. Ergodebooks Richmond, TX, U. This book breaks new ground in how faith and work intersect and are lived out in crosscultural contexts, where job creation and Business as Mission A Comprehensive Guide to Theory and Practice 1st edition transformation go hand in Business as Mission A Comprehensive Guide to Theory and Practice 1st edition. Diplomatic rank. Main article: Economic diplomacy. Various processes and procedures have evolved over time for handling diplomatic issues and disputes. Business as Mission A Comprehensive Guide to Theory and Practice 1st edition the Battle of Baideng BC to the Battle of Mayi BCthe Han Dynasty was forced to uphold a marriage alliance and pay an exorbitant amount of tribute in silk, cloth, grain, and other foodstuffs to the powerful northern nomadic Xiongnu that had been consolidated by Modu Shanyu. International treatiesagreements, alliances, and other manifestations of foreign policy are usually the result of diplomatic negotiations and processes. Representatives from republics were ranked the lowest which often angered the leaders of the numerous German, Scandinavian and Italian republics. -

Diplomats and Diplomacy: Assessing the Influence of Experience in the Implementation of U.S

Diplomats and diplomacy: Assessing the influence of experience in the implementation of U.S. foreign policy by Justin Eric Kidd B.S., Louisiana State University, 1988 M.S., Florida Institute of Technology, 1998 M.M.A., Marine Corps University, 2003 AN ABSTRACT OF A DISSERTATION submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Security Studies Program College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2018 Abstract In 2008, Ambassador’s Neumann and Pickering wrote letters to Senator’s Obama and McCain, with recommendations on qualifications for US Ambassador’s. Both Senator’s had recently received their party’s nomination for President, and Neumann and Pickering took the opportunity to suggest qualifications they believed were necessary for US ambassadors to perform their diplomatic tasks better. Their letters suggested that career ambassadors perform better, and they recommended that political appointees be limited to ten percent. The historical average has been roughly thirty percent. They also recommended that ambassadors have previous regional experience, and be knowledgeable about the countries in which they would be assigned, as well as speak the local language. What their letters were missing was evidence these traits actually make a difference in how well ambassadors perform their roles. In fact, this evidence is missing from the extant literature describing ambassadorial roles and responsibilities. This dissertation seeks to quantitatively and qualitatively analyze Neumann’s and Pickering’s qualifications, marking the first time this important subject has been examined using social science methodology. Diplomats and diplomacy: Assessing the influence of experience in the implementation of U.S.