Reviews / Comptes Rendus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cross-Border Ties Among Protest Movements the Great Plains Connection

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for Spring 1997 Cross-Border Ties Among Protest Movements The Great Plains Connection Mildred A. Schwartz University of Illinois at Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Schwartz, Mildred A., "Cross-Border Ties Among Protest Movements The Great Plains Connection" (1997). Great Plains Quarterly. 1943. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/1943 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. CROSS .. BORDER TIES AMONG PROTEST MOVEMENTS THE GREAT PLAINS CONNECTION MILDRED A. SCHWARTZ This paper examines the connections among supporters willing to take risks. Thus I hypoth political protest movements in twentieth cen esize that protest movements, free from con tury western Canada and the United States. straints of institutionalization, can readily cross Protest movements are social movements and national boundaries. related organizations, including political pro Contacts between protest movements in test parties, with the objective of deliberately Canada and the United States also stem from changing government programs and policies. similarities between the two countries. Shared Those changes may also entail altering the geography, a British heritage, democratic prac composition of the government or even its tices, and a multi-ethnic population often give form. Social movements involve collective rise to similar problems. l Similarities in the efforts to bring about change in ways that avoid northern tier of the United States to the ad or reject established belief systems or organiza joining sections of Canada's western provinces tions. -

FEDERAL ELECTIONS 2018: Election Results for the U.S. Senate and The

FEDERAL ELECTIONS 2018 Election Results for the U.S. Senate and the U.S. House of Representatives Federal Election Commission Washington, D.C. October 2019 Commissioners Ellen L. Weintraub, Chair Caroline C. Hunter, Vice Chair Steven T. Walther (Vacant) (Vacant) (Vacant) Statutory Officers Alec Palmer, Staff Director Lisa J. Stevenson, Acting General Counsel Christopher Skinner, Inspector General Compiled by: Federal Election Commission Public Disclosure and Media Relations Division Office of Communications 1050 First Street, N.E. Washington, D.C. 20463 800/424-9530 202/694-1120 Editors: Eileen J. Leamon, Deputy Assistant Staff Director for Disclosure Jason Bucelato, Senior Public Affairs Specialist Map Design: James Landon Jones, Multimedia Specialist TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Preface 1 Explanatory Notes 2 I. 2018 Election Results: Tables and Maps A. Summary Tables Table: 2018 General Election Votes Cast for U.S. Senate and House 5 Table: 2018 General Election Votes Cast by Party 6 Table: 2018 Primary and General Election Votes Cast for U.S. Congress 7 Table: 2018 Votes Cast for the U.S. Senate by Party 8 Table: 2018 Votes Cast for the U.S. House of Representatives by Party 9 B. Maps United States Congress Map: 2018 U.S. Senate Campaigns 11 Map: 2018 U.S. Senate Victors by Party 12 Map: 2018 U.S. Senate Victors by Popular Vote 13 Map: U.S. Senate Breakdown by Party after the 2018 General Election 14 Map: U.S. House Delegations by Party after the 2018 General Election 15 Map: U.S. House Delegations: States in Which All 2018 Incumbents Sought and Won Re-Election 16 II. -

Excerpted from James Gustav Speth, America, Rising to Its Dream (Forthcoming, Yale U.P., Fall 2012) * How Can We Gauge What

!"#$%&'$()*%+,)-.,$/)01/'.2)3&$'45))!"#$%&'()*%+%,-)./)01+)2$#'")34/$15&/"%,-()6'7#)89:9()4'77);<=;>)) 6) 7+8)#.9)8$):.1:$)84.')4./)4.&&$9$()'+)1/);9)'4$)&./')*$8)($#.($/).9() 84$%$)8$)/'.9()'+(.<=)>9$)8.<)'+).9/8$%)'4;/)?1$/';+9);/)'+)@++A).')4+8)8$) #+,&.%$)8;'4)+'4$%)#+19'%;$/);9)A$<).%$./B)3+)@$'C/)@++A).').):%+1&)+*).(2.9#$() ($,+#%.#;$/DD'4$)#+19'%;$/)+*)'4$)>%:.9;E.';+9)*+%)!#+9+,;#)F++&$%.';+9).9() G$2$@+&,$9'),;91/)'4$)*+%,$%)3+2;$')H@+#)#+19'%;$/5)I$";#+5)J1%A$<5)K+%$.5) L#[email protected](5)M1"$,H+1%:5).9()0%$$#$B)J4$)%$,.;9;9:)#+19'%;$/N9;9$'$$9)9+')#+19';9:) '4$)O9;'$()3'.'$/N#.9)H$)'4+1:4')+*)./)+1%)&$$%)#+19'%;$/B)P4.')8$)/$$)84$9)8$) @++A).')'4$/$)#+19'%;$/);/)'4.')'4$)O9;'$()3'.'$/);/)9+8).')+%)2$%<)9$.%)'4$)H+''+,);9) .)4+/')+*);,&+%'.9').%$./B)J+)+1%):%$.')/4.,$5)Q,$%;#.)9+8)4./RS) T)'4$)4;:4$/')&+2$%'<)%.'$5)H+'4):$9$%.@@<).9()*+%)#4;@(%$9U) T)'4$):%$.'$/');9$?1.@;'<)+*);9#+,$/U) T)'4$)@+8$/'):+2$%9,$9')/&$9(;9:)./).)&$%#$9'.:$)+*)0GV)+9)/+#;.@)&%+:%.,/) *+%)'4$)(;/.(2.9'.:$(U) T)'4$)@+8$/')/#+%$)+9)'4$)OWC/);9($")+*)X,.'$%;.@)8$@@DH$;9:)+*)#4;@(%$9YU) T)'4$)8+%/')/#+%$)+9)'4$)OWC/):$9($%);9$?1.@;'<);9($"U) T)'4$)@+8$/')/+#;.@),+H;@;'<U) T)'4$)4;:4$/')&1H@;#).9()&%;2.'$)$"&$9(;'1%$)+9)4$.@'4)#.%$)./).)&$%#$9'.:$)+*) 0GV5)<$').##+,&.9;$()H<)'4$)4;:4$/'R) D);9*.9'),+%'.@;'<)%.'$) D)&%$2.@$9#$)+*),$9'.@)4$.@'4)&%+H@$,/) D)+H$/;'<)%.'$) D)&$%#$9'.:$)+*)&$+&@$):+;9:)8;'4+1')4$.@'4)#.%$)(1$)'+)#+/') D)@+8)H;%'4)8$;:4')#4;@(%$9)&$%)#.&;'.)Z$"#$&')*+%)-.&.9[) !"#$%&'()*+$%"$,"-%*+!./)0/&&-%*&")/0"#-)+*-" ! -1$%2"3+*4"*4/"&4$0*/&*"1+,/"/5)/#*-%#6"-*"7+0*4"8/5#/)*",$0"9/%(-0:"-%." -

Who's Going to Dance with Somebody Who Calls You a Main Streeter" Communism, Culture, and Community in Sheridan County, Montana, 1918,1934

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for 1995 "WHO'S GOING TO DANCE WITH SOMEBODY WHO CALLS YOU A MAIN STREETER" COMMUNISM, CULTURE, AND COMMUNITY IN SHERIDAN COUNTY, MONTANA, 1918,1934 Gerald Zahavi University of Albany Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Zahavi, Gerald, ""WHO'S GOING TO DANCE WITH SOMEBODY WHO CALLS YOU A MAIN STREETER" COMMUNISM, CULTURE, AND COMMUNITY IN SHERIDAN COUNTY, MONTANA, 1918,1934" (1995). Great Plains Quarterly. 1083. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/1083 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. "WHO'S GOING TO DANCE WITH SOMEBODY WHO CALLS YOU A MAIN STREETER" COMMUNISM, CULTURE, AND COMMUNITY IN SHERIDAN COUNTY, MONTANA, 1918,1934 GERALD ZAHAVI ""'1: 1 he Catholics and the Lutherans met the So began Logan's long career in Sheridan train," recalled Bernadine Logan, a former County. The year was 1930, and she had just schoolteacher in Plentywood, Montana, "to arrived from North Dakota, a fresh Cum Laude get the nab on the new teachers, any crop graduate of Jamestown College.2 The social that would come in. Did they take care of and cultural walls that divided the commu us women teachers! We had a list of the nity were at once unambiguously defined for people with whom we were not to associ her-with a simple list. -

The Nonpartisan League

FURTHER READINGS ON The Nonpartisan League “The history of the League is a compelling chapter in the struggle by farmers throughout our country’s history. The dramatic story of the NPL’s rapid rise to power and equally rapid decline has long been of interest to historians and other scholars … The League appeals to nonacademic readers as an exciting story of political and social confrontation played out by seemingly larger-than-life characters.”1 The standard work on the Nonpartisan League remains Robert Loren Morlan’s Political Prairie Fire: The National Nonpartisan League, 1915-1922 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1955); reprinted by Greenwood Press (1974) and Minnesota Historical Society Press (1985). Morlan's well- written, evocative account depends largely on League sources and offers an interpretation favorable to the organization. Morlan’s work includes an extensive bibliography of books, government documents, pamphlets, articles, theses and archival documents regarding the history of the League. In 1985 the Minnesota Historical Society Press published an updated bibliography of works about the League, The Nonpartisan League 1915-22: An Annotated Bibliography, by Patrick K. Coleman and Charles R. Lamb. Their bibliography includes works that have become available since Morlan’s book was published. Another major work is NPL journalist Herber Gaston's The Nonpartisan League (New York: Harcourt, Brace & Howe, 1920); it is totally undocumented, but is the most often cited of the "first generation histories." Other early works include Charles Edward Russell’s The Non-Partisan League (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1920), and Andrew A. Bruce’s Non-Partisan League (New York: Macmillan Co., 1921). -

THE INTERNATIONALIST, but Are Asked to Give Credit

1 : Land Secured Memberships From the very first the question has been asked regarding the se- lished, which will market their goods for them at a saving, which will curity that would be given the investor. Heretofore, it has not been assist them in purchasing, and which will in other ways secure them the custom to give such security. But now the arrangements have been a greater share in the product of their labor, and save them from ezploi- completed which permit members to be LAND SECURED. tation in many ways. The Llano Co-operative Colony is the only one which has ever been organized to combine this security of ownership with the advantages of HOW TO PURCHASE A LAND-SECURED MEMBERSHIP complete co-operation. First send for an Application for Membership form. This must be Under the new arrangement, every member is taken in on probation. secured from the Membership Department v of the Llano Co-operative This is protection to the colony, protection to the member himself, pro- Colony at Stables or Leesville, Louisiana. The post office address is tection to every other member. Leesville; the colony is a Stables. Under this system, each member may come to the colony on proba- This application form will ask many questions. It will be passed on tion. They will not be accepted on any other grounds. by the Membership Department of the Board of Directors. If it is ac- Expeirence has taught the colony that this is the only just and fair cepted, the member may then pay out and will be given a deed to a way. -

Farm Women of the Nonpartisan League / Karen Starr

FARM WOMEN RESTING from her labor, a lone woman is silhouetted against a sky that dominates the land. In a winter-dark OF THE room, a woman bends over her sewing. On the porch of a white frame house, a woman stands squinting against the sun, one band smoothing her apron, the other on the NONPARTISAN screen door. Our images of midwestern farm women are visual. LEAGUE Their words and stories, like those of many women, have almost been lost to memory. Despite the efforts to un cover such ""lost" history, the record of rural women still Karen Starr remains for the most part buried in the past. This is ' For recent pioneering works on rural women, see, for example, Glenda Riley, Frontierswoman: The Iowa Experience (Ames, 1981); Elizabeth Hampsten, Read This Only to Your- .selfi The Private Writings of Midwestern Women, 1880-1910 (Bloomington, Ind., 1982); and Sherry Thomas, We Didn't partly due to a general dilemma facing historians of a Have Much, But We Sure Had Plenty (Garden Citv, N.Y., people too busy or unlettered to have left written clues 1981). about the pattern of their existence. But iu the case of ^Dorothy St. Arnold, "Family Reminiscence," part 3, p. rural people, such invisibility to history is also a result of [11], in division of archives and manuscripts, Minnesota His the geography of country life and the home-centered torical Society (MHS). nature of farm work. Whatever the cause of the relative silence of country women, their lost words are important to us today. The majority of midwesterners' foremothers are from the land, and their story is part of our history.' Life on the farms of the midwestern plains in the first two decades of the 20tli century was not easy. -

Index to Archivaria Numbers 1 to 54, 1975–2002

Index to Archivaria Numbers 1 to 54, 1975–2002 Index by bookmark: editing & indexing AAAC. See Archival Association of Atlantic Canada AACR2. See Anglo American Cataloguing Rules, 2d ed. AAQ. See Association des archivistes du Québec Abdication Crisis, The: Are Archivists Giving Up Their Cultural Responsibil- ity?, 40:173–81 Abella, Irving Oral History and the Canadian Labour Movement, 4:115–121 Abiding Conviction, An: Maritime Baptists and Their World (review article), 30:114–17 Aboriginal archives documentary approach, 33:117–24 Métis archive project, 8:154–57 See also Aboriginal peoples; Aboriginal records Aboriginal peoples bibliography, archival sources, Yukon (book review), 28:185 clothing traditions (exhibition review), 40:243–45 Hudson’s Bay Company fur trade (review article), 12:121–26 trade, pre-1763 (book review), 8:186–87 Indian Affairs administration (book review), 25:127–30 land claims archives and, 9:15–32 research handbook (book review), 16:169–71 ledger drawings (exhibition review), 40:239–42 literature by (book review), 18:281–84 missionaries and, since 1534, Canada (book review), 21:237–39 New Zealand Maori and archives, reclaiming the past, 52:26–46 4 Archivaria 56 Northwest Coast artifacts (book review), 23:161–64 and British Navy (book review), 21:252–53 treaties historical evidence (review article), 53:122–29 Split Lake Indians, 17:261–65 and White relations (book review), 4:245–47 in World War I (book review), 48:223–27 See also Aboriginal archives; Aboriginal records; names of specific Native groups Aboriginal -

“Read and Be Convinced:” the Image of the Nonpartisan League in Its

“READ AND BE CONVINCED:” THE IMAGE OF THE NONPARTISAN LEAGUE IN ITS CREATIVE PRODUCTION, THE EARLY HISTORIES, AND WIDER POPULAR CULTURE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the North Dakota State University of Agriculture and Applied Science By John Edward Hest In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major Program: History July 2018 Fargo, North Dakota North Dakota State University Graduate School Title “READ AND BE CONVINCED:” THE IMAGE OF THE NONPARTISAN LEAGUE IN ITS CREATIVE PRODUCTION, THE EARLY HISTORIES, AND WIDER POPULAR CULTURE By John Edward Hest The Supervisory Committee certifies that this disquisition complies with North Dakota State University’s regulations and meets the accepted standards for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: Thomas Isern Chair Angela Smith Mark Meister Approved: 7/6/18 Mark Harvey Date Department Chair ABSTRACT In this thesis, I examine the image of the Nonpartisan League in several different contexts, arguing that the League carefully crafted their advocative political image and their opponents painted them as disloyal socialists. The Nonpartisan League was an agrarian radical political movement beginning in North Dakota in 1915, and both its proponents and opponents created powerful images of it. I first examine the creative output of two Leaguers, the poet Florence Borner and the cartoonist John Miller Baer. I then transition to four competing histories of the Nonpartisan League, published from 1920-21, by Herbert Gaston, Charles Edward Russell, William Langer, and Andrew Bruce, all of whom craft divergent images of the League dependent upon their vantage point. -

The Nebraska State Council of Defense and the Nonpartisan League, 1917-1918

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: The Nebraska State Council of Defense and the Nonpartisan League, 1917-1918 Full Citation: Robert N Manley, “The Nebraska State Council of Defense and the Nonpartisan League, 1917- 1918,” Nebraska History 43 (1962): 229-252. URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/NH1962CouncilDefense.pdf Date: 12/10/2010 Article Summary: As the National Nonpartisan League sought to establish a state organization in Nebraska near the end of World War I, it encountered powerful resistance from the Nebraska State Council of Defense. The Council asserted that the League’s policies were disloyal, a threat to the war effort and to American society in general. Emotionalism stirred by wartime tensions increased opposition to the League. Eventually the League chose to withdraw from Nebraska to avoid the risk of extended court battles with the Council of Defense. -

National Nonpartisan League

M 182A P· 1 M 182A National Nonpartisan League. Printed Materials, undated and 1910-1928. 4 rolls positive microfilm. Originals in the Minnesota Historical Society. Collation of the originals: 2.5 feet. This microfilm reproduces printed materials (undated and 1910-1928) relating to the National Nonpartisan League. It is a valuable supple- ment to the microfilm edition of the League's records issued by the Minnesota Historical Society in 1969. Although some items in this edition were filmed in their entirety in the 1969 edition, and the title pages of many others were included as a bibliographic aid, much of the material in this edition does not appear in the earlier edition. HISTORICAL SKETCH The National Nonpartisan League, a political protest organization of farmers and workers, was organized in North Dakota in 1915 to combat economic and political exploitation of spring-wheat farmers; it spread rapidly through the midwestern and northwestern states during the early years of World War I. The League's reform program was heavily socialistic, and the organization encountered intense opposition, led by forces that felt threatened by its success. Prior to the United States' entry into World War I, these opponents attempted to discredit the League by accusing its leaders of being socialists, anarchists, and members of the 'In- dustrial Workers of the World. Following the nation's entry into the war, they attempted to brand the organization and its followers disloyal, seditious, and pro-German. During the post-war "Red Scare," they again returned to their pre-war themes. The League declined almost as rapidly as it had risen and by 1924 no longer existed as a national organization. -

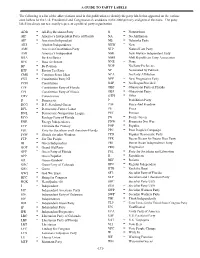

A GUIDE to PARTY LABELS -171- the Following Is a List of the Abbreviations Used in This Publication to Identify the Party Labels

A GUIDE TO PARTY LABELS The following is a list of the abbreviations used in this publication to identify the party labels that appeared on the various state ballots for the U.S. Presidential and Congressional candidates in the 2008 primary and general elections. The party label listed may not necessarily represent a political party organization. ADB = All-Day Breakfast Party N = Nonpartisan AIF = America’s Independent Party of Florida NA = No Affiliation AIP = American Independent NB = Nebraska Party AKI = Alaskan Independence NEW = New AMC = American Constitution Party NLP = Natural Law Party AMI = America’s Independent NMI = New Mexico Independent Party BBA = Back to Basics NMR = NMI Republican Party Association BFS = Boss for Senate NNE = None BP = By Petition NOP = No Party Preference BTP = Boston Tea Party NP = Nominated by Petition CMS = Common Sense Ideas NPA = No Party Affiliation CNJ = Constitution Party NJ NPP = New Progressive Party CON = Constitution NSP = No Slogan Provided CPF = Constitution Party of Florida OBF = Objectivist Party of Florida CPI = Constitution Party of Illinois OBJ = Objectivist Party CRV = Conservative OTH = Other D = Democratic P = Prohibition Party DCG = D.C. Statehood Green PAF = Peace And Freedom DFL = Democratic-Farmer Labor PE = Peace DNL = Democratic-Nonpartisan League PET = Petition ECO = Ecology Party of Florida PG = Pacific Green ENE = Energy Independence PNW = Prosperity Not War ETP = Eliminate the Primary POP = Populist FSL = Party for Socialism and Liberation-Florida PPC = Poor People's Campaign