In Buddhist Cosmological and Soteriological Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Is Time?: Yogācāra-Buddhist Meditation on the Problem of the External World in the Treatise on the Perfection of Consciousness-Only (Cheng Weishi Lun)

DOI: 10.4312/as.2016.4.1.35-57 35 What is Time?: Yogācāra-Buddhist Meditation on the Problem of the External World in the Treatise on the Perfection of Consciousness-only (Cheng weishi lun) Jianjun LI*1 Abstract Because it asserts that there is consciousness-only (vijñapti-mātratā), the difficulty in philo- sophically approaching the Yogācāra-Buddhist text Cheng weishi lun centers on the problem of the external world. This paper is based on a review by Lambert Schmithausen that, specif- ically with regard to the problem of the external world, questions Dan Lusthaus’s phenom- enological investigation of the CWSL. In it I point out that the fundamental temporality of consciousness brought to light by the Yogacaric revelation of the incessant differentiation of consciousness (vijñāna-parināma� ) calls into question every temporally conditioned, and hence appropriational, understanding of vijñapti-mātratā. Therefore, the problem of the external world cannot be approached without taking into account the temporality of con- sciousness, which, furthermore, compels us to face the riddle of time. Keywords: time, vijñapti-mātratā, Cheng weishi lun, Dan Lusthaus, Lambert Schmithausen Izvleček Budistično jogijsko besedilo Cheng weishi lun zagovarja trditev, da obstaja samo zavest (vijñapti-mātratā), zato se filozofski pristop tega besedila usmeri na problem zunanjega sveta. Ta članek temelji na recenziji Lamberta Schmithasena, ki se ob upoštevanju prob- lema zunanjega sveta ukvarja s fenomenološkimi preiskavami CWSL-ja Dana Lusthausa. V njem sem poudaril, da je zaradi odvisnosti zavesti od časa, ki jo poudarja razodevanje nenehnega spreminjanja zavesti pri jogi (vijñāna-parināma� ), vprašljivo vsako časovno po- gojeno, in zato večkrat prisvojeno, razumevanje pojma vijñapti-mātratā. -

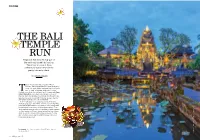

THE BALI TEMPLE RUN Temples in Bali Share the Top Spot on the Must-Visit List with Its Beaches

CULTURE THE BALI TEMPLE RUN Temples in Bali share the top spot on the must-visit list with its beaches. Take a look at some of these architectural marvels that dot the pretty Indonesian island. TEXT ANURAG MALLICK he sun was about to set across the cliffs of Uluwatu, the stony headland that gave the place its name. Our guide, Made, explained that ulu is ‘land’s end’ or ‘head’ in Balinese, while watu is ‘stone’. PerchedT on a rock at the southwest tip of the peninsula, Pura Luhur Uluwatu is a pura segara (sea temple) and one of the nine directional temples of Bali protecting the island. We gaped at the waves crashing 230 ft below, unaware that the real spectacle was about to unfold elsewhere. A short walk led us to an amphitheatre overlooking the dramatic seascape. In the middle, around a sacred lamp, fifty bare-chested performers sat in concentric rings, unperturbed by the hushed conversations of the packed audience. They sat in meditative repose, with cool sandalwood paste smeared on their temples and flowers tucked behind their ears. Sharp at six, chants of cak ke-cak stirred the evening air. For the next one hour, we sat open-mouthed in awe at Bali’s most fascinating temple ritual. Facing page: Pura Taman Saraswati is a beautiful water temple in the heart of Ubud. Elena Ermakova / Shutterstock.com; All illustrations: Shutterstock.com All illustrations: / Shutterstock.com; Elena Ermakova 102 JetWings April 2017 JetWings April 2017 103 CULTURE The Kecak dance, filmed in movies such as There are four main types of temples in Bali – public Samsara and Tarsem Singh’s The Fall, was an temples, village temples, family temples for ancestor worship, animated retelling of the popular Hindu epic and functional temples based on profession. -

A Distant Mirror. Articulating Indic Ideas in Sixth and Seventh Century

Index pp. 535–565 in: Chen-kuo Lin / Michael Radich (eds.) A Distant Mirror Articulating Indic Ideas in Sixth and Seventh Century Chinese Buddhism Hamburg Buddhist Studies, 3 Hamburg: Hamburg University Press 2014 Imprint Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (German National Library). The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. The online version is available online for free on the website of Hamburg University Press (open access). The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek stores this online publication on its Archive Server. The Archive Server is part of the deposit system for long-term availability of digital publications. Available open access in the Internet at: Hamburg University Press – http://hup.sub.uni-hamburg.de Persistent URL: http://hup.sub.uni-hamburg.de/purl/HamburgUP_HBS03_LinRadich URN: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn/resolver.pl?urn:nbn:de:gbv:18-3-1467 Archive Server of the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek – http://dnb.d-nb.de ISBN 978-3-943423-19-8 (print) ISSN 2190-6769 (print) © 2014 Hamburg University Press, Publishing house of the Hamburg State and University Library Carl von Ossietzky, Germany Printing house: Elbe-Werkstätten GmbH, Hamburg, Germany http://www.elbe-werkstaetten.de/ Cover design: Julia Wrage, Hamburg Contents Foreword 9 Michael Zimmermann Acknowledgements 13 Introduction 15 Michael Radich and Chen-kuo Lin Chinese Translations of Pratyakṣa 33 Funayama Toru -

The Teachings on Momentariness Found in Xuanzang's

불교학연구 (Korea Journal of Buddhist Studies) 제66호(2021.3) pp. 1∼49 10.21482/jbs.66..20213.1 Why Change Is the Only Constant: The Teachings on Momentariness Found in Xuanzang’s Translation of the Abhidharma Treatises of Saṅghabhadra* Ernest Billings (Billy) Brewster Lecturer, Iona College [email protected] I. Introduction III. Untangling the Knots in the Theory of II. Saṅghabhadra on the Constancy of the Continuum of Nine Factors Change IV. Conclusion Summary Within the Abhidharma literature, the doctrinal discussions on momentariness composed by the fifth-century C.E. Indic theorist, Saṅghabhadra, and rendered into Chinese by the pilgrim and scholar-monk, Xuanzang (602?–667 C.E.), stand as rigorous and detailed defenses of the Buddhist tenet of momentariness. This paper examines several passages on the doctrine of momentariness that are extant only within Xuanzang’s Chinese translations of two treatises by Saṅghabhadra, the Treatise Conforming to the Correct Logic of Abhidharma (Sanskrit, hereafter Skt. *Abhidharmanyāyānusāraśāstra; Chinese, hereafter Chi. Apidamo shun zhengli lun 阿毘達磨順正理論) and the Treatise Clarifying the Treasury of Abhidharma Tenets (Skt. * I would like to express my gratitude to Dr. Jakub Zamorski for numerous comments, suggestions, and corrections on the translations. I thank Dr. John Makeham for commenting on my paper as a panel respondent at the meeting of the European Association for Chinese Philosophy meeting in Ghent in 2019. The three anonymous reviewers also provided invaluable feedback, which I have tried to incorporate wherever possible. Why Change Is the Only Constant: The Teachings on Momentariness Found in Xuanzang’s Translation … 1 *Abhidharmasamayapradīpikāśāstra; Chi. Apidamo zang xianzong lun 阿毘達磨顯宗論). -

On Doctrinal Similarities Between Sthiramati and Xuanzang

JIABS Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies Volume 29 Number 2 2006 (2008) The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies (ISSN 0193-600XX) is the organ of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, Inc. As a peer- reviewed journal, it welcomes scholarly contributions pertaining to EDITORIAL BOARD all facets of Buddhist Studies. JIABS is published twice yearly. KELLNER Birgit Manuscripts should preferably be sub- KRASSER Helmut mitted as e-mail attachments to: Joint Editors [email protected] as one single file, complete with footnotes and references, BUSWELL Robert in two different formats: in PDF-format, and in Rich-Text-Format (RTF) or Open- CHEN Jinhua Document-Format (created e.g. by Open COLLINS Steven Office). COX Collet GÓMEZ Luis O. Address books for review to: HARRISON Paul JIABS Editors, Institut für Kultur - und Geistesgeschichte Asiens, Prinz-Eugen- VON HINÜBER Oskar Strasse 8-10, A-1040 Wien, AUSTRIA JACKSON Roger JAINI Padmanabh S. Address subscription orders and dues, KATSURA Shōryū changes of address, and UO business correspondence K Li-ying (including advertising orders) to: LOPEZ, Jr. Donald S. Dr Jérôme Ducor, IABS Treasurer MACDONALD Alexander Dept of Oriental Languages and Cultures SCHERRER-SCHAUB Cristina Anthropole SEYFORT RUEGG David University of Lausanne CH-1015 Lausanne, Switzerland SHARF Robert email: [email protected] STEINKELLNER Ernst Web: http://www.iabsinfo.net TILLEMANS Tom Fax: +41 21 692 30 45 Subscriptions to JIABS are USD 40 per year for individuals and USD 70 per year for libraries and other institutions. For informations on membership in IABS, see back cover. Cover: Cristina Scherrer-Schaub Font: “Gandhari Unicode” designed by Andrew Glass (http://andrewglass.org/ fonts.php) © Copyright 2008 by the International Association of Buddhist Studies, Inc. -

The Concept of Existence (Bhava) in Early Buddhism Pranab Barua

The Concept of Existence (Bhava) in Early Buddhism Pranab Barua, Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University, Thailand The Asian Conference on Ethics, Religion & Philosophy 2021 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract The transition in Dependent Origination (paṭiccasamuppāda) between clinging (upādāna) and birth (jāti) is often misunderstood. This article explores the early Buddhist philosophical perspective of the relationship between death and re-birth in the process of following bhava (uppatti-bhava) and existing bhava (kamma-bhava). It additionally analyzes the process of re- birth (punabbhava) through the karmic processes on the psycho-cosmological level of becoming, specifically how kamma-bhava leads to re-becoming in a new birth. The philosophical perspective is established on the basis of the Mahātaṇhāsaṅkhaya-Sutta, the Mahāvedalla-Sutta, the Bhava-Sutta (1) and (2), the Cūḷakammavibhaṅga-Sutta, the Kutuhalasala-Sutta as well as commentary from the Visuddhimagga. Further, G.A. Somaratne’s article Punabbhava and Jātisaṃsāra in Early Buddhism, Bhava and Vibhava in Early Buddhism and Bhikkhu Bodhi’s Does Rebirth Make Sense? provide scholarly perspective for understanding the process of re-birth. This analysis will help to clarify common misconceptions of Tilmann Vetter and Lambert Schmithausen about the role of consciousness and kamma during the process of death and rebirth. Specifically, the paper addresses the role of the re-birth consciousness (paṭisandhi-viññāṇa), death consciousness (cūti-viññāṇa), life continuum consciousness (bhavaṅga-viññāṇa) and present consciousness (pavatti-viññāṇa) in the context of the three natures of existence and the results of action (kamma-vipāka) in future existences. Keywords: Bhava, Paṭiccasamuppāda, Kamma, Psycho-Cosmology, Punabbhava iafor The International Academic Forum www.iafor.org Prologue Bhava is the tenth link in the successive flow of human existence in the process of Dependent Origination (paṭiccasamuppāda). -

Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism, Revised Edition

REVISED EDITION John Powers ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 1 Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 2 ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 3 Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism revised edition by John Powers Snow Lion Publications ithaca, new york • boulder, colorado ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 4 Snow Lion Publications P.O. Box 6483 • Ithaca, NY 14851 USA (607) 273-8519 • www.snowlionpub.com © 1995, 2007 by John Powers All rights reserved. First edition 1995 Second edition 2007 No portion of this book may be reproduced by any means without prior written permission from the publisher. Printed in Canada on acid-free recycled paper. Designed and typeset by Gopa & Ted2, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Powers, John, 1957- Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism / by John Powers. — Rev. ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN-13: 978-1-55939-282-2 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-55939-282-7 (alk. paper) 1. Buddhism—China—Tibet. 2. Tibet (China)—Religion. I. Title. BQ7604.P69 2007 294.3’923—dc22 2007019309 ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 5 Table of Contents Preface 11 Technical Note 17 Introduction 21 Part One: The Indian Background 1. Buddhism in India 31 The Buddha 31 The Buddha’s Life and Lives 34 Epilogue 56 2. Some Important Buddhist Doctrines 63 Cyclic Existence 63 Appearance and Reality 71 3. Meditation 81 The Role of Meditation in Indian and Tibetan Buddhism 81 Stabilizing and Analytical Meditation 85 The Five Buddhist Paths 91 4. -

Buddhist Phenomenology: a Philosophical Investigation of Yogācāra Buddhism and the Ch’Eng Wei-Shih Lun

Journal of Buddhist Ethics ISSN 1076-9005 http://www.buddhistethics.org/ Volume 16, 2009 Buddhist Phenomenology: A Philosophical Investigation of Yogācāra Buddhism and the Ch’eng Wei-shih Lun Reviewed by Alexander L. Mayer Department of Religion University of Illinois [email protected] Copyright Notice: Digital copies of this work may be made and distributed provided no change is made and no alteration is made to the content. Reproduction in any other format, with the exception of a single copy for private study, requires the written permission of the author. All enquiries to: [email protected] A Review of Buddhist Phenomenology: A Philosophical Investigation of Yogācāra Buddhism and the Ch’eng Wei-shih Lun Alexander L. Mayer * Buddhist Phenomenology: A Philosophical Investigation of Yogācāra Buddhism and the Ch’eng Wei-shih Lun. By Dan Lusthaus. Curzon Critical Studies in Buddhism Series. London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2002, xii + 611 pages, ISBN: 0-7007-1186-4 (hardcover), US $65.00. This book is an expanded version of Dan Lusthaus’s Temple University dissertation (1989). It is built around Vasubandhu’s Triṃśikā (Thirty Stanzas) and its Chinese exegesis in the Cheng weishi lun, composed in mid seventh century China by Xuanzang. Buddhist Phenomenology ex- plores two major theses: first, it endeavors to establish that classical Yogācāra is a phenomenological and epistemological investigation of Buddhist questions concerning human existence and is not a form of me- taphysical or ontological idealism; second, it tries to show that classical Yogācāra thought evinces a much stronger continuity with earlier lines of Buddhist thought than often assumed.1 The assessment of Yogācāra in the past has been complicated by its complex interrelation with other branches of Buddhist exegesis such as Sarvāstivāda, Sautrāntika, Prajñāpāramitā (including Mādhyamaka), and Tathāgatagarbha, and by the coexistence of several lines of thought * Department of Religion, University of Illinois. -

The Special Theory of Pratītyasamutpāda: the Cycle Of

THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BUDDHIST STUDIES EDITOR-IN-CHIEF A.K. Narain University of Wisconsin, Madison, USA EDITORS tL. M.Joshi Ernst Steinkellner Punjabi University University oj Vienna Patiala, India Wien, Austria Alexander W. Macdonald Jikido Takasaki Universile de Paris X University of Tokyo Nanterre, France Tokyo, Japan Bardwell Smith Robert Thurman Carleton College Amherst College Northfield, Minnesota, USA Amherst, Massachusetts, USA ASSISTANT EDITOR Roger Jackson Fairfield University Fairfield, Connecticut, USA Volume 9 1986 Number 1 CONTENTS I. ARTICLES The Meaning of Vijnapti in Vasubandhu's Concept of M ind, by Bruce Cameron Hall 7 "Signless" Meditations in Pali Buddhism, by Peter Harvey 2 5 Dogen Casts Off "What": An Analysis of Shinjin Datsuraku, by Steven Heine 53 Buddhism and the Caste System, by Y. Krishan 71 The Early Chinese Buddhist Understanding of the Psyche: Chen Hui's Commentary on the Yin Chihju Ching, by Whalen Im 85 The Special Theory of Pratityasamutpdda: The Cycle of Dependent Origination, by Geshe Lhundub Sopa 105 II. BOOK REVIEWS Chinese Religions in Western Languages: A Comprehensive and Classified Bibliography of Publications in English, French and German through 1980, by Laurence G. Thompson (Yves Hervouet) 121 The Cycle of Day and Night, by Namkhai Norbu (A.W. Hanson-Barber) 122 Dharma and Gospel: Two Ways of Seeing, edited by Rev. G.W. Houston (Christopher Chappie) 123 Meditation on Emptiness, by Jeffrey Hopkins Q.W. de Jong) 124 5. Philosophy of Mind in Sixth Century China, Paramdrtha 's 'Evolution of Consciousness,' by Diana Y. Paul (J.W.deJong) 129 Diana Paul Replies 133 J.W.deJong Replies 135 6. -

Meningkatkan Mutu Umat Melalui Pemahaman Yang Benar Terhadap Simbol Acintya (Perspektif Siwa Siddhanta)

MENINGKATKAN MUTU UMAT MELALUI PEMAHAMAN YANG BENAR TERHADAP SIMBOL ACINTYA (PERSPEKTIF SIWA SIDDHANTA) Oleh: I Gusti Made Widya Sena Dosen Fakultas Brahma Widya IHDN Denpasar Abstract God will be very difficult if understood with eye, to the knowledge of God through nature, private and personification through the use of various symbols God can help humans understand God's infinite towards the unification of these two elements, namely the unification of physical and spiritual. Acintya as a symbol or a manifestation of God 's Omnipotence itself . That what really " can not imagine it turns out " could imagine " through media portrayals , relief or statue. All these symbols are manifested Acintya it by taking the form of the dance of Shiva Nataraja, namely as a depiction of God's omnipotence , to bring in the actual symbol " unthinkable " that have a meaning that people are in a situation where emotions religinya very close with God. Keywords: Theology, Acintya, Siwa Siddhanta & Siwa Nataraja I. PENDAHULUAN Kehidupan sebagai manusia merupakan hidup yang paling sempurna dibandingkan dengan makhluk ciptaan Tuhan lainnya, hal ini dikarenakan selain memiliki tubuh jasmani, manusia juga memiliki unsur rohani. Kedua unsur ini tidak dapat dipisahkan dan saling melengkapi diantara satu dengan lainnya. Layaknya garam di lautan, tidak dapat dilihat secara langsung tapi terasa asin ketika dikecap. Jasmani manusia difungsikan ketika melakukan berbagai macam aktivitas di dunia, baik dalam memenuhi kebutuhan hidup (kebutuhan pangan, sandang dan papan), reproduksi, bersosialisasi dengan makhluk lainnya, dan berbagai aktivitas lainnya, sedangkan tubuh rohani difungsikan dalam merasakan, memahami dan membangun hubungan dengan Sang Pencipta, sehingga ketenangan, keindahan dan kebijaksanaan lahir ketika penyatuan diantara kedua unsur ini berjalan selaras, serasi dan seimbang. -

The Teaching of Buddha”

THE TEACHING OF BUDDHA WHEEL OF DHARMA The Wheel of Dharma is the translation of the Sanskrit word, “Dharmacakra.” Similar to the wheel of a cart that keeps revolving, it symbolizes the Buddha’s teaching as it continues to be spread widely and endlessly. The eight spokes of the wheel represent the Noble Eightfold Path of Buddhism, the most important Way of Practice. The Noble Eightfold Path refers to right view, right thought, right speech, right behavior, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right meditation. In the olden days before statues and other images of the Buddha were made, this Wheel of Dharma served as the object of worship. At the present time, the Wheel is used internationally as the common symbol of Buddhism. Copyright © 1962, 1972, 2005 by BUKKYO DENDO KYOKAI Any part of this book may be quoted without permission. We only ask that Bukkyo Dendo Kyokai, Tokyo, be credited and that a copy of the publication sent to us. Thank you. BUKKYO DENDO KYOKAI (Society for the Promotion of Buddhism) 3-14, Shiba 4-chome, Minato-ku, Tokyo, Japan, 108-0014 Phone: (03) 3455-5851 Fax: (03) 3798-2758 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.bdk.or.jp Four hundred & seventy-second Printing, 2019 Free Distribution. NOT for sale Printed Only for India and Nepal. Printed by Kosaido Co., Ltd. Tokyo, Japan Buddha’s Wisdom is broad as the ocean and His Spirit is full of great Compassion. Buddha has no form but manifests Himself in Exquisiteness and leads us with His whole heart of Compassion. -

What the Upanisads Teach

What the Upanisads Teach by Suhotra Swami Part One The Muktikopanisad lists the names of 108 Upanisads (see Cd Adi 7. 108p). Of these, Srila Prabhupada states that 11 are considered to be the topmost: Isa, Kena, Katha, Prasna, Mundaka, Mandukya, Taittiriya, Aitareya, Chandogya, Brhadaranyaka and Svetasvatara . For the first 10 of these 11, Sankaracarya and Madhvacarya wrote commentaries. Besides these commentaries, in their bhasyas on Vedanta-sutra they have cited passages from Svetasvatara Upanisad , as well as Subala, Kausitaki and Mahanarayana Upanisads. Ramanujacarya commented on the important passages of 9 of the first 10 Upanisads. Because the first 10 received special attention from the 3 great bhasyakaras , they are called Dasopanisad . Along with the 11 listed as topmost by Srila Prabhupada, 3 which Sankara and Madhva quoted in their sutra-bhasyas -- Subala, Kausitaki and Mahanarayana Upanisads --are considered more important than the remaining 97 Upanisads. That is because these 14 Upanisads are directly referred to by Srila Vyasadeva himself in Vedanta-sutra . Thus the 14 Upanisads of Vedanta are: Isa, Kena, Katha, Prasna, Mundaka, Mandukya, Aitareya, Taittiriya, Brhadaranyaka, Chandogya, Svetasvatara, Kausitaki, Subala and Mahanarayana. These 14 belong to various portions of the 4 Vedas-- Rg, Yajus, Sama and Atharva. Of the 14, 8 ( Brhadaranyaka, Chandogya, Taittrirya, Mundaka, Katha, Aitareya, Prasna and Svetasvatara ) are employed by Vyasa in sutras that are considered especially important. In the Gaudiya Vaisnava sampradaya , Srila Baladeva Vidyabhusana shines as an acarya of vedanta-darsana. Other great Gaudiya acaryas were not met with the need to demonstrate the link between Mahaprabhu's siksa and the Upanisads and Vedanta-sutra.