Promoting Open File Formats and Open Source at Dartmouth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

School and Email Systems

Email system survey: Top 50 US Colleges US Note Email system Server queried Greeting News School ranking 1 Harvard University Mail2World imap.college.harvard.edu OK Mail2World IMAP4 Server 2.5 ready Sun Java SMS imap.princeton.edu OK [CAPABILITY IMAP4 IMAP4rev1 ACL QUOTA LITERAL+ NAMESPACE UIDPLUS CHILDREN BINARY LANGUAGE XSENDER X-NETSCAPE XSERVERINFO Princeton University 1 AUTH=PLAIN] Messaging Multiplexor (Sun Java(tm) System Messaging Server 6.2-5.05 (built Feb 16 2006)) Unknown mail.yale.edu OK [CAPABILITY IMAP4REV1 LOGIN-REFERRALS AUTH=PLAIN AUTH=LOGIN] pantheon-po14.its.yale.edu IMAP4rev1 2002.336 at Mon, 26 Jul 2010 14:10:23 Yale University 3 -0400 (EDT) Dovecot imap-server.its.caltech.edu OK Dovecot ready. Cyrus mail.alumni.caltech.edu OK posteaux1.caltech.edu Cyrus IMAP4 v2.2.12-Invoca-RPM-2.2.12-10.el4_8.4 server ready 4 California Institute of Technology Dovecot imap.gps.caltech.edu OK dovecot ready. Dovecot theory.caltech.edu OK dovecot ready. 4 Massachusetts Institute of Technology Unable to find a server to query (username.mail.mit.edu)Unknown 4 Stanford University Zimbra zm01.stanford.edu OK zm01.stanford.edu Zimbra IMAP4rev1 server ready Zimbra mailbox.zimbra.upenn.edu OK mailbox.zimbra.upenn.edu Zimbra IMAP4rev1 service ready 4 University of Pennsylvania Exchange 2010 webmail.wharton.upenn.edu OK The Microsoft Exchange IMAP4 service is ready. Dovecot imap.nevis.columbia.edu OK [CAPABILITY IMAP4rev1 LITERAL+ SASL-IR LOGIN-REFERRALS ID ENABLE AUTH=PLAIN] Dovecot ready. Lotus Domino equinox.law.columbia.edu OK Domino IMAP4 -

Fall 2003 Class News by Michelle Sweetser I Hope Everyone Had a Good Summer! It’S Been a Crazy Fall Here in Ann Arbor As I Wrap up Classes and Begin the Job Search

Alma Matters The Class of 1999 Newsletter Fall 2003 Class News by Michelle Sweetser I hope everyone had a good summer! It’s been a crazy fall here in Ann Arbor as I wrap up classes and begin the job search. I have no idea where I’ll be after December - maybe in your area! It’s both frightening and exciting. This being the first newslet- ter after the summer wedding sea- son, expect to read about a number of marriages in the coming pages. West The first of the marriage an- nouncements is that of Christopher Rea and Julie Ming Wang, who mar- ried on June 2 in Yosemite National Park. In attendance were Russell Talbot, Austin Whitman, Jessica Reiser ’97, Jon Rivinus, Christian Bennett, Genevieve Bennett ’97, Pete Land and Wendy Pabich '88 stop to pose in front of the the Jennifer Mui, and Stephen Lee. Bremner Glacier and the Chugach Mountains in Wrangell - St. The couple honeymooned in Greece Elias National Park, Alaska. Wendy and Pete were there working and are now living in New York City. as consultants for the Wild Gift, a new fellowship program for Both Cate Mowell and environmental students that includes a three-week trek through the Alaskan wilderness. Caroline Kaufmann wrote in about Anna Kate Deutschendorf’s beau- tiful wedding to Jaimie Hutter ’96 in Aspen. It was Cate quit her job at Nicole Miller in August a reportedly perfect, cool, sunny day, and the touch- and is enjoying living at the beach in Santa Monica, ing ceremony took place in front of a gorgeous view CA. -

Hurricane Football

ACCENT SPORTS INSIDE NEWS: Miami Herald • The UM Ring • The 12th-ranked Miami investigative journalists _*&£ Hurricanes look to rebound from Jeff Leen and Don Van Theatre's latest Natta spoke to students production is a their disappointing Orange Bowl Wednesday morning. smashing success. loss against a high-powered Page 4 •£__fl_]__5? Rutgers offense. OPINION: Is "Generation X" a Page 8 PaaelO misnomer? Pago 6 MlVEfftlTY OF •II •! _ - SEP 3 01994 BEJERVE W$t jWiamt hurricane VOLUME 72, NUMBER 9 CORAL GABLES, FLA. FRIDAY. SEPTEMBER 30. 1994 Erws Elections Commission improves voting process ByCOMJANCKO According to Commissioner-at- students will be allowed to cam make voting more convenient, and Large Jordan Schwartsberg, the paign." Office of Registrar Records in the BRIEFS Hurricane Staff Writer increase the total voter turnout. Ashe Building, room 249. Student Government has made Elections Commission is working The elections will be held Oct. In the past, approximately 500 to changes in the way elections will be to make the election system run 24 to 26. Students will vote on 600 students out of a total 8,000 RAT MASCOT run and how students will vote. smoothly. computers in the residential col on campus voted in the elections. The senate positions for each of The Elections Commission, a "To help make the campaigning leges and in computer labs. To vote, students need to pick up the residence halls, the Apartment NAMED AT PROMO easier for the candidates, we plan Last year students travelled to branch of SG, appoint commission their Personal Identification Num Area, Fraternity Row, Commuter ers for one-year terms to plan and to make many of the regulations the specific voting booths around North, Commuter Central, and The Rathskeller Advisory Board implement the logistics of elec clearer," Schwartsberg said. -

Attribute-Based, Usefully Secure Email

Dartmouth College Dartmouth Digital Commons Dartmouth College Ph.D Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 8-1-2008 Attribute-Based, Usefully Secure Email Christopher P. Masone Dartmouth College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.dartmouth.edu/dissertations Part of the Computer Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Masone, Christopher P., "Attribute-Based, Usefully Secure Email" (2008). Dartmouth College Ph.D Dissertations. 26. https://digitalcommons.dartmouth.edu/dissertations/26 This Thesis (Ph.D.) is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Dartmouth Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dartmouth College Ph.D Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Dartmouth Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Attribute-Based, Usefully Secure Email A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Computer Science by Christopher P. Masone DARTMOUTH COLLEGE Hanover, New Hampshire August, 2008 Examining Committee: (chair) Sean W. Smith, Ph.D. David F. Kotz, Ph.D. Christopher J. Bailey-Kellogg, Ph.D. Denise L. Anthony, Ph.D. M. Angela Sasse, Ph.D. Charles K. Barlowe, PhD Dean of Graduate Studies Abstract A secure system that cannot be used by real users to secure real-world processes is not really secure at all. While many believe that usability and security are diametrically opposed, a growing body of research from the field of Human-Computer Interaction and Security (HCISEC) refutes this assumption. All researchers in this field agree that focusing on aligning usability and security goals can enable the design of systems that will be more secure under actual usage. -

Sebenarnya Apa Sih Yang Dimaksud Dengan Perangkat Lunak Email Client

Aplikasi email client Sebenarnya apa sih yang dimaksud dengan Perangkat Lunak Email Client ? Jika kita telaah asal kata dari kalimat tersebut, bahwa email (Electronic Mail) merupakan suatu proses dan cara pengiriman pesan atau gambar melalui internet ke 1 org atau lebih. Pada dasarnya email sama dengan surat biasa (snail mail) yang harus melewati beberapa kantor pos sebelum sampai ke tujuannya, begitu dikirimkan oleh seseorang melalui komputer yang tersambung ke internet sebuah email masuk ke beberapa komputer lain di sepanjang jaringan internet yang disebut dengan mail server. Ketika email tersebut sampai ke server yang menjadi tujuan (seperti yang ditunjuk pada alamat email – kepada siapa kita menulis email), maka email tersebut disimpan pada sebuah emailbox. Si pemilik alamat email baru bisa mendapatkan email itu kalau yang bersangkutan mengecek emailbox-nya. Nah untuk mengakses emailbox, kita perlu melakukan login melalui interface atau tampilan berbasis web yang disediakan oleh Pemilik Mail Server kita. Untuk melakukan login tentu saja dibutuhkan koneksi internet yang lumayan kencang dan tidak putus-putus alias RTO (Request Time Out). Untuk Mempermudah kita membaca email serta pengiriman email tanpa harus login melalui tampilan web, kita membutuhkan aplikasi yang yang biasa disebut Email Client. Aplikasi apa saja yang termasuk Email Client ? Beberapa aplikasi yang termasuk jenis ini diantaranya adalah : (Tabel Comparison) User Client Creator Cost Software license Interface Alpine University of Washington Free Apache License CLI Balsa gnome.org Free GNU GPL GUI Becky! Internet Rimarts US$40 proprietary software GUI Mail BlitzMail Dartmouth College Free BSD GUI Citadel citadel.org Free GNU GPL Web Claws Mail the Claws Mail team Free GNU GPL GUI Courier Mail Server Cone Free GNU GPL CLI developers Correo Nick Kreeger Free GNU GPL GUI Courier Micro Computer Free (as of version (formerly Systems, Inc., continued proprietary software GUI 3.5) Calypso) by Rose City Software Dave D. -

Final Report University of Maryland Student Email

FINAL REPORT UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND STUDENT EMAIL COMMITTEE May 15, 2011 COMMITTEE MEMBERS Michael Ball, Smith School of Business, Prof & Assoc Dean (Chair) David Barks, OIT-TSS-Enterprise Internet Svcs, Manager (non-voting) Patrick Beasley, Alumni Association, Assistant Director of Technology Anne Bowden, President’s Office, University Counsel (non-voting) Bill Dorland, Undergraduate Studies - Honors College, Prof & Director Allison Druin, iSchool, Associate Dean Jeff McKinney, Electrical and Computer Eng, Director of Computer Services Dan Navarro, BSOS, Director of Academic Computing Services Dai-An Tran, Student Affairs Resident Life, Assistant Director Amitabh Varshney, Institute for Advanced Computer Studies, Prof & Director Luigi Alvarado, Grad Student Zach Cohen, Student – BSOS, Legislator SGA Mariela Garcia Colberg, Grad student Jacob Crider, Student – ARHU, Legislator SGA Tomek Kott, Grad Student Elizabeth Moran, Student, Smith School of Business, Legislator SGA Morgan Parker, Student, CMPS Legislator SGA Background In the Fall of 2010, the University’s Office of Information Technology (OIT) examined alternatives for providing student email services in the 2011-2012 academic year and beyond. This examination was motivated by several factors, including these prominent two: • the existing Mirapoint-based system was outdated and in need of hardware and software upgrades; • there were many attractive competing alternatives. OIT investigated this issue. Their investigation included a survey of students and also an identification and analysis of several alternatives. Their report to the University IT Council is attached (Appendix 1). The OIT analysis found that a number of important non-technical issues, including privacy and security concerns, should be taken into account in making this decision. Therefore, it was recommended that a campus-wide committee be formed to address this issue. -

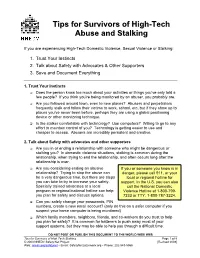

Tips for Survivors of High-Tech Abuse and Stalking

TTiippss ffoorr SSuurrvviivvoorrss ooff HHiigghh--TTeecchh AAbbuussee aanndd SSttaallkkiinngg If you are experiencing High-Tech Domestic Violence, Sexual Violence or Stalking: 1. Trust Your Instincts 2. Talk about Safety with Advocates & Other Supporters 3. Save and Document Everything 1. Trust Your Instincts Does the person know too much about your activities or things you’ve only told a few people? If you think you’re being monitored by an abuser, you probably are. Are you followed around town, even to new places? Abusers and perpetrators frequently stalk and follow their victims to work, school, etc, but if they show up to places you’ve never been before, perhaps they are using a global positioning device or other monitoring technique. Is the stalker comfortable with technology? Use computers? Willing to go to any effort to maintain control of you? Technology is getting easier to use and cheaper to access. Abusers are incredibly persistent and creative. 2. Talk about Safety with advocates and other supporters Are you in or ending a relationship with someone who might be dangerous or stalking you? In domestic violence situations, stalking is common during the relationship, when trying to end the relationship, and often occurs long after the relationship is over. Are you considering ending an abusive If you or someone you know is in relationship? Trying to stop the abuse can danger, please call 911, or your be a very dangerous time, but there are steps local or regional hotline for you can take to try to increase your safety. support. In the U.S. you can also Specially trained advocates at a local call the National Domestic program or regional/national hotline can help Violence Hotline at 1-800-799- you plan for safety and discuss options. -

Towards Usefully Secure Email Chris Masone and Sean Smith Department of Computer Science Dartmouth College Cmasone,[email protected]

1 Towards Usefully Secure Email Chris Masone and Sean Smith Department of Computer Science Dartmouth College cmasone,[email protected] Abstract— When users’ mental models don’t match the bring human mental models and the behavior of systems way the underlying systems work, problems can arise. into closer alignment, thus avoiding these problems, we For human-based security systems to be effective, we believe software must be designed to explicitly leverage believe that is important to identify the tasks involved at which humans excel (and at which computers do not), and the people who use it; lay out the goals of the system, then design the system accordingly. To demonstrate this identify the tasks involved at which humans excel (and principle, we are building Attribute-Based, Usefully Secure at which computers do not), and then design the system Email (ABUSE), a system that leverages users by enabling accordingly. them to build a decentralized, non-hierarchical PKI to express their trust relationships with each other, and then To demonstrate this design principle, we have chosen to to use this PKI to manage their trust in people with whom build Attribute-Based, Usefully Secure Email (ABUSE), they correspond via secure email. Our design puts humans into the system—to do things that humans are good at a system that leverages users by enabling them to build but machines are not—at both the creation of credentials a decentralized, non-hierarchical PKI to express their as well as the interpretation of credentials. In this paper, trust relationships with each other, and then use this we discuss why secure email is an interesting proving PKI to manage their trust in people with whom they ground for our design ideas, set out the architecture of correspond via secure email. -

Central Florida Future, June 4, 1997

University of Central Florida STARS Central Florida Future University Archives 6-4-1997 Central Florida Future, June 4, 1997 Part of the Mass Communication Commons, Organizational Communication Commons, Publishing Commons, and the Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/centralfloridafuture University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Central Florida Future by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation "Central Florida Future, June 4, 1997" (1997). Central Florida Future. 1375. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/centralfloridafuture/1375 By NORA R. KULIESH years had to bring. A partial She is a goddess of the the tinuing her educ~tion at UCF. Managing Editor drama scholarship to Western atre," said Agnes co-star Jamie "When I graduated from Carolina University in McCoy. Western I was guiding rafts For 25-year-old Nonalee Cullowhee, N.C., might have Not only did Davis act in down the N antahala River and Davis, acting has been her one brought her away from Cocoa numerous performances dur even though it was fun and I true love since age 3, but now Beach but not from acting and ing her college career, she met some incredible people, it it is much more than a child not from rising as a star in her tried her hand at directing as . wasn't what I wanted to be hood fancy - it }s a career. -

Spring 2003 Content Final

seconds and is almost negligible in the full scheme of the database. Future projects may include creating scripting exceeds all expectations. We strongly recommend that the Through a joint collaboration between the Technical system. This further supports reliability. on the mail server that copies and pastes this text foundation proceed with this project. Services Staff and the Engineering Department, Noblet Through definition and testing of current state of automatically. For demonstration purposes, the current The Safety Blitz system completely solves the has led a team of Dartmouth undergraduates and the art technology and specifications, we improved our method is reliable and clear. When the emergency text shortcomings in current college campus security. It is a Technical Service staff in engineering the new handheld solution and eventually created a final prototype that is entered, the computer will automatically display all reliable, user-friendly system that can be implemented PDA. The Blitzberry is a two way communicator for simulates the Safety Blitz system. Our prototype, as crucial information, including location and Map Code, at all colleges with wireless network capabilities. As the wireless network 802.11b that would use WiFi as described in testing, consists of two basic parts: a laptop in one organized window (please refer to Appendix colleges in the United States compete against each other transport. It could be used for Blitzmail, IM connections computer with a wireless card (simulating the Safety Blitz A for a sample of the database display window.) The by continually modifying and bettering their campuses, to AOL, MSN, Yahoo, and support for two way audio. -

How to Get Email Headers

How to get email headers Sri Lanka Computer Emergency Readiness Team | Coordination Center Sri Lanka Computer Emergency Response Team The following guide will provide instructions on how to extract headers from various email clients and programs. Sri Lanka Computer Emergency Response Team The following guide will provide instructions on how to extract headers from various email clients and programs. Sri Lanka Computer Emergency Response Team Index 1. Outlook 1.1 Outlook Express 4, 5 and 66............................................................................. 5 1.2 Outlook 98, Outlook 2000, Outlook 2003........................................................ 66. 1.3 Outlook 2007 ................................................................................................... 77 1.4 Outlook Express for Macintosh ....................................................................... 7 1.5 Outlook Web Access (OWA)........................................................................... 77 2. Microsoft Exchange ............................................................................................ 88 3. Hotmailil ................................................................................................................. 99 4. Gmail.....................................................................................................................10 5. Yahoo Mail ...........................................................................................................11 6. Evolution ..............................................................................................................12 -

Scholarly Information Centers in ARL Libraries. SPEC Kit 175. INSTITUTION Association of Research Libraries, Washington, D.C

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 341 404 IR 053 906 AUTHOR Allen, Nancy, Comp.; Godden, Irene, Comp. TITLE Scholarly Information Centers in ARL Libraries. SPEC Kit 175. INSTITUTION Association of Research Libraries, Washington, D.C. Office of Management Stuedes. REPORT NO ISSN-0160-3582 PUB DATE Jun 91 NOTE 179p. AVAILABLE FROM Systems and Procedures Exchange Center, Office of Management Services, 1527 New Hampshire Ave, NW, Washington, DC 20036. PUB TYPE Reports - Research/Technical (143) -- Tests/Evaluation Instruments (160) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Academic Libraries; Access to Information; Computer Networks; Electronic Equipment; Guides; Higher Education; *Information Services; *Information Technology; Library Facilities; Library Networks; Library Role; Marketing; Microcomputers; *Online Systems; Policy Formation; *Research Libraries; Technological Advancement; *Telecommunications; Users (Information) ABSTRACT Noting that the rapid evolution of telecommunications technology, the relentless advancement of computing capabilities, and the seemingly endless proliferation of electronic data have had a profound impact on research libraries, this Systems and Procedures Exchange Center (SPEC) kit explores the extent to which these technologies have come together to form "scholarly information centers" in research librezies. A survey of Association of Research Libraries (ARL) member libraries was conducted in October 1990 to gather information about how research libraries are dealing with the impact of the "electronic revolution" on user services, from equipment and organization to funding and the role of professionals. Based on the data received from the 86 institutions that responded to the questionnaire, this report presents a summary of the survey and its findings, a copy of the questionnaire, and selected survey data. Examples of programming and policy statements, facilities descriptions, user guides, and marketing and publicity announcements are then presented.