Access to Infrastructure Nadine I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Royal Mail Annual Report

Royal Mail plc Royal Mail plc Annual Report and Financial Statements Royal Mail plc 2014-15 Annual Report FinancialAnnual Statements and 2014-15 Strategic report Governance Financial statements Other information Strategic report Who we are 02 Financial and operating performance highlights 04 Chairman’s statement 05 Chief Executive Officer’s review 07 Market overview 12 Our business model 14 Our strategy 16 Key performance indicators 18 UK Parcels, International & Letters (UKPIL) 21 General Logistics Systems (GLS) 23 Financial review 24 Business risks 31 Corporate Responsibility 36 Governance Chairman’s introduction to Corporate Governance 41 Board of Directors 43 Statement of Corporate Governance 47 Chief Executive’s Committee 58 Directors’ Report 60 Directors’ remuneration report 64 Financial statements Consolidated income statement 77 Consolidated statement of comprehensive income 78 Consolidated statement of cash flows 79 Consolidated balance sheet 80 Consolidated statement of changes in equity 81 Notes to the consolidated financial statements 82 Significant accounting policies 131 Group five year summary (unaudited) 140 Statement of Directors’ responsibilities in respect of 142 Information key the Group financial statements Independent Auditor’s Report to the members of 143 Royal Mail plc Case studies Royal Mail plc – parent Company financial statements 146 This icon is used throughout the document to indicate Other information reporting against a key performance indicator (KPI) Shareholder information 151 Forward-looking statements 152 Annual Report and Financial Statements 2014-15 Who we are Royal Mail is the UK’s pre-eminent delivery company, connecting people, customers and businesses. As the UK’s sole designated Universal Service Provider1, we are proud to deliver a ‘one-price-goes-anywhere’ service on a range of letters and parcels to more than 29 million addresses, across the UK, six-days-a-week. -

Openreach Limited1

Promoting competition and investment in fibre networks: Wholesale Fixed Telecoms Market Review 2021-2026 NON CONFIDENTIAL VERSION 15 May 2020 Foreword This response is provided by Openreach Limited1. Openreach is a wholesale network provider. We support more than 600 Communications Providers (CPs) to connect the 30 million UK homes and business to their networks. We sell our products and services to CPs so they can add their own products and provide their customers with bundled landline, mobile, broadband, TV and data services. Our services are available to everybody and our products have the same prices, terms and conditions, no matter who buys them. 1 Openreach Limited is a wholly owned subsidiary of BT Group Plc. 2 Contents Section 1 Executive Summary 4 Section 2 Market definition and assessing market power 15 Section 3 Pricing of WLA services 30 Section 4 Regulation of geographic discounts and other commercial terms 38 Section 5 Copper retirement 63 Section 6 Duct & Pole Access 69 Section 7 Leased Lines & Dark Fibre Access 114 Section 8 Quality of Service 158 Section 9 Pricing Remedies 227 3 1. Executive Summary Key points 1.1 Openreach is making this response at an unprecedented time as the country focuses on dealing with the challenges posed by COVID-19. Keeping the Nation’s communications network going has never been more important and our current focus is on keeping the UK connected and doing the essential work that is required to maintain and enhance our network. We have responded to this consultation as fully as possible given the current circumstances but would note that the full impact of COVID-19 and the time it will take to fully recovery cannot yet be forecast with any certainty. -

Notice of Meeting 2014

Notice of Meeting 2014 This document is important and requires your immediate attention. If you are in any doubt about the action you should take, you should consult your independent financial adviser. If you have recently sold or transferred your shares in Severn Trent Plc please forward this document to your bank, stockbroker or other agent through or to whom the sale or transfer was effected for delivery to the purchaser or transferee. Dear Shareholder This year’s Annual General Meeting (the ‘Meeting’) will be held at the International Convention Centre in Birmingham on Wednesday 16 July 2014 at 11am and the formal notice of the Meeting is set out overleaf (the ‘Notice’). If you would like to vote on the Resolutions in the Notice but cannot come to the Meeting, please fill in the Form of Proxy sent to you with the Notice and return it to Equiniti (our registrar) as soon as possible. Equiniti must receive the Form of Proxy by 11am on Monday 14 July 2014. Alternatively, you can vote online at www.sharevote.co.uk If you are a registered shareholder holding shares in your own name and have not elected to receive communications in paper form by post or if you have elected to receive paper notification that shareholder communications are available to view online, I can advise you that the Annual Report and Accounts for the year ended 31 March 2014 is now available online at www.severntrent.com Please note that the company operates a Dividend Reinvestment Plan, which gives shareholders the option of using their dividend payments to buy more shares in Severn Trent Plc (the ‘Company’) at favourable commission rates. -

Question 3.1: Do You Agree with Ofcom’S Proposal to Set Synchronised Charge Controls for LLU and WLR?

NON-CONFIDENTIAL VERSION OFCOM CHARGE CONTROL REVIEW FOR LLU AND WLR SERVICES – CONSULTATION ISSUED 31 MARCH 2011 RESPONSE BY EVERYTHING EVERYWHERE LIMITED A. INTRODUCTION Everything Everywhere Limited (EE) welcomes the opportunity to respond to Ofcom’s important consultation on the next charge control review for local loop unbundling (LLU) and wholesale line rental (WLR) services, issued on 31 March 2011 (the Consultation). This Consultation is of key commercial and competitive significance for the success of EE’s Orange Home fixed voice and broadband business going forward. In this regard we note that, whilst during the course of 2011 we have been moving from a direct shared metallic path facility (SMPF) and WLR based mode of providing these retail services to providing our retail services through a wholesale arrangement with BT, [][]. The comments in this response represent the views of EE. It should be noted that the views of EE’s shareholders and those of the holding companies and ultimate parent companies may vary from these views. Those parts of this response marked with [] and highlighted in blue are confidential to EE. B. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY EE’s experience of LLU regulation and market conditions in the UK as an SMPF based service provider has been a telling one. Most notably, following the initial successes of Ofcom LLU policy in stimulating SMPF based retail broadband competition, progressive changes to regulatory investment ladder have resulted in us witnessing over the last five years the market exit of a very large proportion of the SMPF “early adopters” (e.g. Tiscali, AOL, Pipex, Bulldog). In May 2011, we have also seen the total number of unbundled lines in the UK falling rather than growing for the first time in several years, from 7.62 million lines in April 2011 to 7.56 million lines in May 20111. -

Openreach Limited Annual Report and Financial Statements 31 March

Openreach Limited Annual Report and Financial Statements 31 March 2020 Registered number: 10690039 Openreach Limited Contents: Page Corporate Information 2 Strategic Report 3 Directors’ Report 6 Statement of Directors’ Responsibilities 12 Independent Auditor’s Report to the Members of Openreach Limited 13 Profit and Loss Account 16 Balance Sheet 17 Statement of Changes in Equity 18 Notes to the Financial Statements 19 1 Openreach Limited Corporate Information Directors E Astle B Barber (resigned 31 May 2020) A Barron (appointed 1 June 2020) E Benison M Davies S Lowth R McTighe C Selley Secretary J Furmston Auditor KPMG LLP 15 Canada Square, London. E14 5GL Registered Office 123 Judd Street London WC1H 9NP 2 Openreach Limited Strategic Report The directors present their strategic report for Openreach Limited (“the Company”) for the year ended 31 March 2020. Business Review Openreach Limited was set up as part of the regulatory agreement reached between British Telecommunications plc and Ofcom under the Digital Communications Review (“DCR”). During the year the Company has continued to carry out its principal activities which are to set the Openreach strategy (within British Telecommunications plc’s overall strategic framework), employ Openreach employees and to oversee and manage the performance of the Openreach Customer Facing Unit (“CFU”), a division of British Telecommunications plc on behalf of British Telecommunications plc within a framework agreed between the Company and British Telecommunications plc. British Telecommunications plc has committed to fund the costs of the services provided by the Company, initially in accordance with the Transitional Agreement contract executed on 15 December 2017 between the Company and British Telecommunications plc and subsequently in accordance with the Agency & Services Agreement which came into effect on 1 October 2018, resulting in the automatic termination of the Transitional Agreement. -

BT Group Regulatory Affairs, Response Remove All 4

Annex to the BT response to Ofcom’s consultation on promoting competition and investment in fibre networks – Wholesale Fixed Telecoms Market Review 2021-26 29 May 2020 Non - confidential version Branding: only keep logos if the response is on behalf of more than one brand, i.e. BT/Openreach joint response or BT/EE/Plusnet joint response. Comments should be addressed to: Remove the other brands, or if it is purely a BT BT Group Regulatory Affairs, response remove all 4. BT Centre, London, EC1A 7AJ [email protected] BT RESPONSE TO OFCOM’S CONSULTATION ON COMPETITION AND INVESTMENT IN FIBRE NETWORKS 2 Contents CONTENTS .................................................................................................................................................. 2 A1. COMPASS LEXECON: REVIEW OF OFCOM'S APPROACH TO ASSESSING ULTRAFAST MARKET POWER 3 A2. ALTNET ULTRAFAST DEPLOYMENTS AND INVESTMENT FUNDING ...................................................... 4 A3. EXAMPLES OF INCREASING PRICE PRESSURE IN BUSINESS TENDERING MARKETS .............................. 6 A4. MARKET ANALYSIS AND REMEDIES RELATED TO PHYSICAL INFRASTRUCTURE ................................... 7 Our assessment of Ofcom’s market analysis ............................................................................................ 8 Our assessment of Ofcom’s remedies .................................................................................................... 12 A5. RISKS BORNE BY INVESTORS IN BT’S FIBRE INVESTMENT ................................................................ -

Telefónica O2 Uk Limited Response To: “Review of The

TELEFÓNICA O2 UK LIMITED RESPONSE TO: “REVIEW OF THE WHOLESALE LOCAL ACCESS MARKET” PUBLISHED BY OFCOM JUNE 2010 Telefónica O2 UK Limited Wellington Street Slough Berkshire SL1 1YP UK t +44 (0)113 272 2000 www.o2.com Telefónica O2 UK Limited Registered in England & Wales no. 1743099 Registered Office: 260 Bath Road Slough Berkshire SL1 4DX UK TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.................................................................................................................... 4 INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................................................4 THE IMPORTANCE OF A BALANCED REGULATORY REGIME ....................................................................5 MAKING IT ALL WORK FOR CUSTOMERS................................................................................................5 PROMOTING COMPETITIVE DIFFERENTIATION FOR CUSTOMERS.............................................................6 ARTIFICIALLY CONSTRAINING THE PRODUCT SET WILL LIMIT THE ROLLOUT OF NGA ..........................6 O2 RECOMMENDATIONS........................................................................................................................7 General ............................................................................................................................................7 The risk of gaming ...........................................................................................................................7 Improve -

European Telecom Services: the Rise of the Wholesale-Only Model

Equity Research 3 May 2018 European Telecom Services INDUSTRY UPDATE The rise of the Wholesale-Only model European Telecom Services Until recently it was almost unthinkable that any company would consider creating POSITIVE a third expensive parallel Telecom infrastructure, competing with EU incumbents Unchanged and cable, given the high barrier to entry/cost of rollout, relatively stable competition plus mature nature of the industry. However, we are now seeing European Telecom Services strategic moves across a number of European markets, with Open Fiber in Italy the Maurice Patrick highest profile case study, and others following. In this detailed report we analyse +44 (0)20 3134 3622 Open Fiber’s prospects, its key success factors, and identify risks to other EU [email protected] markets. We conclude that Italy is in many ways a “perfect storm”, creating a fertile Barclays, UK investment opportunity for alternative infrastructure. Only Germany and the UK are Mathieu Robilliard likely to see wholesale only on a similar scale, given low incumbent FTTH builds and +44 203 134 3288 high service provider interest. Today we downgraded BT to EW and upgraded TEF [email protected] DE to OW, and we believe OW-rated VOD and ORA are de-risked vs. peers. Barclays, UK Open Fiber – Driving cost-effective rollout and high penetration. Open Fiber will Daniel Morris double its FTTH footprint to c5m homes by end-2018, and 19m by 2023. The company +44 (0)20 7773 2113 sees c.50% penetration in “mature” areas, with newly built areas at c.10% and rising, [email protected] per our recent meeting. -

GEC Computers Ltd

V1 January 2015 GEC Computers Ltd. Origins. In 1968 the real-time computing interests of AEI, Elliott-Automation, English Electric, Marconi and GEC, were consolidated into a single company [ref. 1]. It traded initially as Marconi Elliott Computer Systems Ltd (MECS) and then, after 1971, as GEC Computers Ltd. English Electric obtained the non-computing products and the mainframe data processing products were transferred to ICT/ICL. MECS, and GEC Computers, were for many years based at Borehamwood, though the specialist aerospace computing activities were soon transferred to Marconi-Elliott Avionics Systems Ltd. at Rochester. Initially, the range of MECS computers was inherited from Marconi and Elliott-Automation and comprised the MYRIAD series, M2100 series (a small-scale 16-bit multiprocessor for real-time control]), and the 900 series (see below). About 50% of the applications for these computers were described as ‘military’. The other 50% was made up roughly equally of the following applications areas: Industrial, Laboratory, Marine, Education, Traffic control, Communications, Medical. The GEC 900 series of computers [refs. 2- 4], though first introduced in 1961, had a life extending into the 1980s with machines such as the 920ATC. By then developments had for several years been based firmly at Rochester, under various titles such as GEC-Marconi Avionics Ltd. and eventually BAE Systems. The 900 series is described elsewhere, in the Mainframes section of the Our Computer Heritage website. [ref. 2]. The GEC 2000 and 4000 families. By 1970 GEC Computers Ltd. was working at the Computer Research Laboratory (CRL), Borehamwood, on three new computer ranges. These were known internally as Alpha, Beta, and Gamma. -

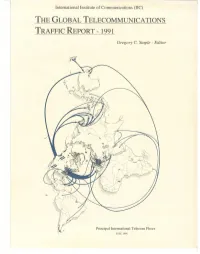

The Global Telecommunications Traffic Report- 1991

International Institute of Communications (IIC) THE GLOBAL TELECOMMUNICATIONS TRAFFIC REPORT- 1991 Gregory C. Staple -Editor Principal International Telecom Flows © HC 1991 THE GLOBAL TELECOMMUNICATIONS TRAFFIC REPORT - 1991 Gregory C. Staple - Editor © Copyright 1991 International Institute of Communications T~S ~S co~,¥ .o./~ DO NOT REPRODUCE The IIC is an independent educational and policy research organi- zation with members in more than 70 countries. It focuses on telecommunications and broadcasting issues on a world-wide basis. Institute publications include a bimonthly magazine, Intermedia, and a range of topical brief’rag papers. IIC publications and reports do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Institute’s officers, trustees or members. Previous IIC reports in this series: 1990 The Global Telecommunications Traffic Boom 1989 Global Telecommunications Traffic Flows and Market Structures For additional copies of this report or other publications, contact: International Institute of Communications Tavistock House South, Tavistock Square, London WCIH 9LF Tel: 071-388-0671/Fax: 071-380-0623/Telex: 24578 IICLDN G Cover Illustration - The cover maps the largest streams of switched international telecommunications traf17c onto a ci~cular projection. Routes shown generally had a two-way flow in 1990 exceeding gO million Minutes of Telecommunication Traf17c (MITT). Some routes have been omitted for presentation purposes. Shaded map areas show major points of origin and destination. Concept: Gregory C. Staple. Illustration: Maryland CartoGraptffcs. ©International Institute of Communications 1991 The Global Telecommunications T:aflqc R#port- 1991 This report could not have been compiled without assistance. Carriers, government departments and regulatory organizations from around the world responded to our informational requests. -

BBC(British Broadcasting Corporation)

영국 방송통신 사업자 보고서 BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation) 영국 공영 방송사이자 세계 최초TV 방송개시 사업자 회사 프로필 桼영국의 공영 방송사이자 세계 최대의 글로벌 방송사로, 상장여부 비상장 1936년 세계 최초로 TV 방송을 개시하였음 설립시기 1927 년 Michael Lyons BBC Trust 회장 주요 인사 -중앙우체국 (General Post Office) 이 1922 년영국방송협회 Mark Thompson BBC 회장 TV (British Broadcasting Corporation, BBC) 라는 명칭으로 사업 분야 라디오 설립된후1927 년왕실칙허장 (Royal Charter) 에근거하여 인터넷 기반 TV 공영방송사가 됨 Broadcasting House 주소 Portland Place London W1A 1AA 桼BBC 는 영국 공영방송으로서의 독립성과 공정성을 유지하기 전화 +44-20-7580-4468 위해BBC 자율규제기관인 BBCTrust 의관리감독을 받으며 매출 49억 9,300 만 파운드 (‘11.03) 영국왕실칙령은10 년 주기로 갱신되어 현재 왕실칙령은 당기순이익 4억 8,290 만 파운드 (’11.03) 2007년제정되어 2016 년말만기될예정임 직원 수 2만 2,899 명 (‘11.03) 홈페이지 www.bbc.co.uk 桼주요 수입원은 영국 가정으로부터 징수하는 연간TV 수신료이며 그 밖에 자체 제작 프로그램의 해외 수출 등을 통해 수익을 올리고 있음 회사 연혁 2012 런던올림픽 주관방송사 - 매년 방송 수신료는 문화미디어스포츠부와 재무성, BBC 의 2010 프리뷰(Freeview) HD 방송 개시 3자 협상을 통해 결정되고 , 이후 의회의 승인으로 채택 2009 프리샛(Freesat) HD 방송 개시 인터넷 기반 방송 서비스 2007 -정부는왕실칙령이만기되는 2016 년까지컬러 TV 와흑백 TV iPlayer 개시 연간 수신료는 각각145.5 파운드와 49 파운드로 동결시키기로 함 1998 디지털 채널BBC 초이스 개시 1995 디지털 오디오 방송 개시 1967BBC 2, 컬러방송 개시 桼BBC 는 영국뿐 아니라 세계 각지에 자체 제작한 프로그램 1964BBC 2 개국 공급을 통해 전 세계 대표 공영방송사업자로써의 독보적인 세계 최초로 정규TV 방송 1936.11 위치를 유지하고 있음 개시 British Broadcasting 1927 Corporation 출범 桼BBC의인터넷서비스인 iPlayer 의이용이급증하고있음 1926BBC 공사화 결정 British Broadcasting - 모바일과 태블릿PC 를 통한 이용이 두드러졌으며 , 2012 년 1 월 부터 1922 Company 설립 4월까지평균적으로월별 19,000 억 만이용건이있었음 영국TVTVTV 채널 시청점유율 재무 현황 현황(2011) Discovery Walt Disney 2% Co Ltd. -

An Post Annual Report

An Post Annual Report Annual An Post An Post An Post Annual Report General Post Office O’Connell Street Dublin 1 Ireland 2008 Contents 2 Mission, Vision and Values 4 Board of Directors and Corporate Information 6 Chairman’s Statement 9 Management 10 Chief Executive’s Review 16 Financial Review 18 Universal Service 21 Sustainability 25 Stamp Issues and Philatelic Publications 28 Index to the Financial Statements For further information on An Post, visit our website: www.anpost.ie The An Post Annual Report is also available in Irish. 1 Our Mission To provide world class postal, distribution and financial services with unrivalled local community access and global connections. Our Vision Working together as a united team, our ambition is to out perform the new competition we face, delivering a better quality service, more efficiently, to more customers by continuously adapting, innovating and implementing change. 2 Our Values Innovative, Change-able Organisation We demonstrate a high ‘capacity to change’, adapting quickly to external threats and opportunities, executing strategies and securing the intended outcomes of negotiated changes on time. Respected Corporate Citizen We enjoy a reputation among all stakeholders as a respected corporate citizen, involved in the community and environmentally responsible. Satisfied, Well-led, Engaged, Responsible Staff We are a team of energised, well-led, responsible people, treated with respect, provided with good opportunities and committed to a performance culture and personal responsibility. Commercially Successful We are a growing, commercially successful business, providing returns to fund investment growth, reward our employees and meet shareholder expectations. Cost Competitive Efficient Operations We run an efficient, cost competitive organisation with streamlined processes and optimal use of technology, that fully support our business objectives and customer needs.