The Lords of the Southern March: Interpretation Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Powerful Arms and Fertile Soil”

“Powerful Arms and Fertile Soil” English Identity and the Law of Arms in Early Modern England Claire Renée Kennedy A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History and Philosophy of Science University of Sydney 2017 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My greatest thanks and appreciation to Ofer Gal, who supervised my PhD with constant interest, insightfulness and support. This thesis owes so much to his helpful conversation and encouraging supervision and guidance. I have benefitted immensely from the suggestions and criticisms of my examiners, John Sutton, Nick Wilding, and Anthony Grafton, to whom I owe a particular debt. Grafton’s suggestion during the very early stages of my candidature that the quarrel between William Camden and Ralph Brooke might provide a promising avenue for research provided much inspiration for the larger project. I am greatly indebted to the staff in the Unit for History and Philosophy of Science: in particular, Hans Pols for his unwavering support and encouragement; Daniela Helbig, for providing some much-needed motivation during the home-stretch; and Debbie Castle, for her encouraging and reassuring presence. I have benefitted immensely from conversations with friends, in and outside the Unit for HPS. This includes, (but is not limited to): Megan Baumhammer, Sahar Tavakoli, Ian Lawson, Nick Bozic, Gemma Lucy Smart, Georg Repnikov, Anson Fehross, Caitrin Donovan, Stefan Gawronski, Angus Cornwell, Brenda Rosales and Carrie Hardie. My particular thanks to Kathryn Ticehurst and Laura Sumrall, for their willingness to read drafts, to listen, and to help me clarify my thoughts and ideas. My thanks also to the Centre for Editing Lives and Letters, University College London, and the History of Science Program, Princeton University, where I benefitted from spending time as a visiting research student. -

Le Coastal Way

Le Coastal Way Une épopée à travers le Pays de Galles thewalesway.com visitsnowdonia.info visitpembrokeshire.com discoverceredigion.wales Où est le Pays de Galles? Prenez Le Wales Way! Comment s’y rendre? Le Wales Way est un voyage épique à travers trois routes distinctes: Le North On peut rejoindre le Pays de Galles par toutes les villes principales du Royaume-Uni, y compris Londres, Wales Way, Le Coastal Way et Le Cambrian Way, qui vous entraînent dans les Birmingham, Manchester et Liverpool. Le Pays de Galles possède son propre aéroport international, contrées des châteaux, au long de la côte et au coeur des montagnes. le Cardiff International Airport (CWL), qui est desservi par plus de 50 routes aériennes directes, reliant ainsi les plus grandes capitales d’Europe et offrant plus de 1000 connections pour les destinations du Le Coastal Way s’étend sur la longueur entière de la baie de Cardigan. C’est une odyssée de 180 monde entier. Le Pays de Galles est également facilement joignable par les aéroports de Bristol (BRS), miles/290km qui sillonne entre la mer azur d’un côté et les montagnes imposantes de l’autres. Birmingham (BHX), Manchester (MAN) et Liverpool (LPL). Nous avons décomposé le voyage en plusieurs parties pour que vous découvriez les différentes destinations touristiques du Pays de Galles: Snowdonia Mountains and Coast, le Ceredigion et A 2 heures de Londres en train le Pembrokeshire. Nous vous présentons chacune de ces destinations que vous pouvez visiter tout le long de l’année selon ces différentes catégories:Aventure, Patrimoine, Nature, Boire et Manger, Randonnée, et Golf. -

Welsh Tribal Law and Custom in the Middle Ages

THOMAS PETER ELLIS WELSH TRIBAL LAW AND CUSTOM IN THE MIDDLE AGES IN 2 VOLUMES VOLUME I1 CONTENTS VOLUME I1 p.1~~V. THE LAWOF CIVILOBLIGATIONS . I. The Formalities of Bargaining . .a . 11. The Subject-matter of Agreements . 111. Responsibility for Acts of Animals . IV. Miscellaneous Provisions . V. The Game Laws \TI. Co-tillage . PARTVI. THE LAWOF CRIMESAND TORTS. I. Introductory . 11. The Law of Punishtnent . 111. ' Saraad ' or Insult . 1V. ' Galanas ' or Homicide . V. Theft and Surreption . VI. Fire or Arson . VII. The Law of Accessories . VIII. Other Offences . IX. Prevention of Crime . PARTVIl. THE COURTSAND JUDICIARY . I. Introductory . 11. The Ecclesiastical Courts . 111. The Courts of the ' Maerdref ' and the ' Cymwd ' IV. The Royal Supreme Court . V. The Raith of Country . VI. Courts in Early English Law and in Roman Law VII. The Training and Remuneration of Judges . VIII. The Challenge of Judges . IX. Advocacy . vi CONTENTS PARTVIII. PRE-CURIALSURVIVALS . 237 I. The Law of Distress in Ireland . 239 11. The Law of Distress in Wales . 245 111. The Law of Distress in the Germanic and other Codes 257 IV. The Law of Boundaries . 260 PARTIX. THE L4w OF PROCEDURE. 267 I. The Enforcement of Jurisdiction . 269 11. The Law of Proof. Raith and Evideilce . , 301 111. The Law of Pleadings 339 IV. Judgement and Execution . 407 PARTX. PART V Appendices I to XI11 . 415 Glossary of Welsh Terms . 436 THE LAW OF CIVIL OBLIGATIONS THE FORMALITIES OF BARGAINING I. Ilztroductory. 8 I. The Welsh Law of bargaining, using the word bargain- ing in a wide sense to cover all transactions of a civil nature whereby one person entered into an undertaking with another, can be considered in two aspects, the one dealing with the form in which bargains were entered into, or to use the Welsh term, the ' bond of bargain ' forming the nexus between the parties to it, the other dealing with the nature of the bargain entered int0.l $2. -

HISTORY of ABERYSTWYTH

HISTORY of ABERYSTWYTH We all think of Aberystwyth as a seaside resort town. The presence of the ruined castle suggests a coloured medieval history, fraught with battles and land forever changing hands between powerful rulers. However, there was evidence of human activity in Aberystwyth long before this time, so we thought it might be worth going through the history of Aberyst- wyth right from the start. The earliest recorded human activity in Aberystwyth area dates back to around 11,500 years ago during the mesolithic period. The mesolithic period signalled the end of a long and arduous ice age, which saw most of the worlds surface covered in ice, leav- ing only the most hardy plants and animals to survive. As the ice retreaded in Mid Wales, this revealed large supplies of stone, including flint at Tan-Y-Bwlch which lies at the foot of Pen Dinas hill. There is strong evidence that the area was used for flint knapping, which involved the shaping of the flint deposits left behind by the retreating ice in order to make weapons for hunting for hunting animals. The flint could be shaped into sharp points, which could be used as primitive spears and other equipment, used by the hunter gatherer to obtain food. Around 3000 years ago there is evidence of an early Celtic ringfort on the site of Pen Dinas. The ringfort is a circular fortified set- tlement which was common throughout Northern Europe in the Bronze and Iron ages. What remains of this particular example at Aberystwyth is now located on private land on Pen Dinas, and can only be accessed by arrangement. -

Welsh Government Summary of Events Following The

Public Accounts Committee - Additional Written Evidence Summary of events following the Statutory Inquiry at Tai Cantref The Statutory Inquiry report was completed in October 2015. The report found multiple instances of mismanagement and misconduct. The report made no comment beyond its brief to establish whether there was evidence to support the serious allegations made by whistle blowers. It made no recommendations or commentary on possible ways forward. Tai Cantref’s Board were given until 13th November 2015 to set out a credible response and plan to deal with the findings of the inquiry. The Welsh Government Regulation Team (the Regulator) considered that the initial response was inadequate in both the association’s acceptance of the findings and its intentions and commitment to tackling the issues raised. The Board was also required to share a copy of the Inquiry with its lenders who were similarly concerned with the response and reserved the right to enforce loan conditions. By this point an event of default had been triggered in Tai Cantref’s loan agreements. Following detailed discussions, including with lenders, the Board was given a second chance to respond to the findings. Shortly after this decision was notified to Tai Cantref, the Chair resigned and an existing Board member was unanimously appointed as the new Chair. The Board then took a number of key decisions which provided assurance it was now seeking to respond to the findings: the Board appointed a consultant to provide immediate support the Board to address the Inquiry findings. three suitably experienced, first language welsh speakers, were co- opted to strengthen the Board. -

Monmouthshire County Council Weekly List of Registered Planning

Monmouthshire County Council Weekly List of Registered Planning Applications Week 31/01/2015 to 06/02/2015 Print Date 10/02/2015 Application No Development Description Application Type SIte Address Applicant Name & Address Agent Name & Address Community Council Valid Date Plans available at Easting / Northing Caerwent DC/2015/00115 Non material amendments (garage doors & garage flat roof section) in relation to Non Material Amendment DC/2012/00578. Northgate House Mr Brian Scaife Old Chepstow Road Northgate House Caerwent Old Chepstow Road Caldicot. NP26 5NZ Caerwent Caldicot. NP26 5NZ Caerwent 30 January 2015 346,927 / 190,764 DC/2015/00089 Side extension to Cranford to form new dwelling. Planning Permission Cranford Ben Luff Maison Design Shirenewton Old Road Cranford 25 Caldicot Road Crick Shirenewton Old Road Rogiet NP26 5UW Crick Caldicot NP26 5UW NP26 3SE Caerwent 04 February 2015 348,732 / 190,262 Caerwent 2 Print Date 10/02/2015 MCC Pre Check of Registered Applications 31/01/2015 to 06/02/2015 Page 2 of 16 Application No Development Description Application Type SIte Address Applicant Name & Address Agent Name & Address Community Council Valid Date Plans available at Easting / Northing Caldicot Castle DC/2015/00111 Single storey extension to rear of dwelling. Planning Permission 40 Wentwood View Mr Spencer Dowse Caldicot 40 Wentwood View NP26 4QA Caldicot NP26 4QA Caldicot 03 February 2015 347,881 / 188,998 DC/2015/00130 Discharge of condition 8 (type and colour of render) and conditon 7 (final archaeological Discharge of Condition -

Your Guide to Centre Rallies in the UK, Ireland and Overseas Cover Designed for Your Needs

2021 Centre Rallies Your guide to Centre Rallies in the UK, Ireland and Overseas Cover designed for your needs Our cover is designed for members who love touring as much as you do. We offer a wide range of products designed with our members in mind including: Award Award winning winning Motorhome and Caravan Cover Campervan Insurance Call: 01342 488 338 Call: 0345 504 0334 Visit: camc.com/caravancover Visit: camc.com/insurance Car Insurance Home Insurance Switch to us and save at least £25 guaranteed* 9/10 choose to renew† Call: 0345 504 0334 Call: 0345 504 0335 Visit: camc.com/carinsurance Visit: camc.com/homeinsurance MAYDAY UK Overseas Emergency Assistance Breakdown Cover with Red Pennant Three cover levels, from just £74** per year Providing European breakdown and medical emergency assistance including cover for COVID-19†† Call: 0800 731 0112 Call: 01342 336 633 Visit: camc.com/mayday Visit: camc.com/redpennant Improving services for you Cover you can trust Make sure you receive the information • Over 50 years’ insurance and and news you want. Keep your profile on cover experience camc.com/myclub up-to-date with your correct • Excess income goes back into your Club details – such as your insurance • Cover designed for tourers like you renewal dates and your outfit type, so we can contact you at the right time with any offers we may have. Visit camc.com/insurance *Premium Saving Guarantee. Offer applies to new customers only and is subject to insurers’ acceptance of the risk, their terms and conditions and cover being arranged on a like-for-like basis. -

Wales & the Welsh Borders

Wales & the Welsh Borders A Journey Through the reserved Ancient Celtic Kingdom rights th th all September 10 - 19 2020 Wales, Castle ruins, meandering medieval streets, and a Visit magnificent Celtic heritage bring the beauty of Wales (2011) to life against a backdrop of rolling green hills and dramatic sea cliffs. Past and present coexist in this distinctive part of the world—the Romans mined for copyright gold, the Tudors founded a dynasty, and the Normans Crown built castles whose ancient remains are scattered along © windy hilltops throughout the countryside. Along the way, Wales’ ancient Celtic heritage was memorialized in a stunning collection of literature and artwork. From the magnificence of Caernarfon to the breathtaking vistas on peaceful St. David’s Peninsula, Harlech Castle we’ll explore the places, personalities, and sweep of history that constitute the haunting beauty of Wales. We’ll also step in and out of ancient market towns like Ludlow and Carmarthen, supposed birthplace of Merlin, located in “the garden of Wales” and visit beautiful villages like Hay-on-Wye, famous for its abundance of antique book stores, and ancient Shrewsbury, with more than 600 historic listed buildings and narrow medieval alleyways. We’ll experience the natural splendor of Snowdonia, with the highest mountain peaks in the country, and the Wye Valley, rich in ancient woodlands, wildlife, and the idyllic setting for the timelessly romantic ruins of Tintern Abbey. Join Discover Europe as we pay homage to great poets and storytellers and journey into the heart and history of ancient Wales. Let the magic of this The cost of this itinerary, per person, double occupancy is: Celtic kingdom come to life on Wales & the Welsh Land only (no airfare included): $4280 Borders. -

The Pembrokeshire (Communities) Order 2011

Status: This is the original version (as it was originally made). This item of legislation is currently only available in its original format. WELSH STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2011 No. 683 (W.101) LOCAL GOVERNMENT, WALES The Pembrokeshire (Communities) Order 2011 Made - - - - 7 March 2011 Coming into force in accordance with article 1(2) and (3) The Local Government Boundary Commission for Wales has, in accordance with sections 54(1) and 58(1) of the Local GovernmentAct 1972(1), submitted to the Welsh Ministers a report dated April 2010 on its review of, and proposals for, communities within the County of Pembrokeshire. The Welsh Ministers have decided to give effect to those proposals with modifications. More than six weeks have elapsed since those proposals were submitted to the Welsh Ministers. The Welsh Ministers make the following Order in exercise of the powers conferred on the Secretary of State by sections 58(2) and 67(5) of the Local Government Act 1972 and now vested in them(2). Title and commencement 1.—(1) The title of this Order is The Pembrokeshire (Communities) Order 2011. (2) Articles 4, 5 and 6 of this Order come into force— (a) for the purpose of proceedings preliminary or relating to the election of councillors, on 15 October 2011; (b) for all other purposes, on the ordinary day of election of councillors in 2012. (3) For all other purposes, this Order comes into force on 1 April 2011, which is the appointed day for the purposes of the Regulations. Interpretation 2. In this Order— “existing” (“presennol”), in relation to a local government or electoral area, means that area as it exists immediately before the appointed day; “Map A” (“Map A”), “Map B” (“Map B”), “Map C” (“Map C”), “Map D” (“Map D”), “Map E” (“Map E”), “Map F” (“Map F”), “Map G” (“Map G”), “Map H” (“Map H”), “Map I” (“Map (1) 1972 c. -

Lindors Country House Hotel the Fence, St

LINDORS COUNTRY HOUSE HOTEL THE FENCE, ST. BRIAVELS, LYDNEY, GLOUCESTERSHIRE LINDORS COUNTRY HOUSE HOTEL The Fence, St. Briavels, Lydney, Gloucestershire, GL15 6RB Gloucester 25.1 miles, Bristol 27.7 miles, Cheltenham 31.6 miles (all distances are approximate) “A 23 bedroom country house hotel, located in the Wye Valley” • 23 en suite bedrooms • 5 lodges • “Stowes” restaurant with 64 covers • Lounge and Sun Lounge with dedicated lounge menu • 3 conference rooms with a total capacity of 114 delegates • Leisure facilities including an indoor swimming pool, tennis court, and croquet lawn • Car parking for circa 40 cars • Set in around 24.4 acres of gardens and grounds LINDORS COUNTRY WYE VALLEY AND THE HOUSE HOTEL FOREST OF DEAN The Lindors Country House Hotel is located The Hotel sits in the Wye Valley Area on Stowe Road, approximately 1.3 miles of Outstanding Natural Beauty, which from the Village of St Briavels. The village offers dramatic landscapes and nature was built in the early 12th century, with a trails with historic attractions such as landmark Castle and Church. Chepstow Castle, Dewstow Gardens, Tintern Abbey and the Roman Fort in The main part of the Lindors Country House Caerleon. was constructed in 1660, with the larger part of the house being added later. The Hotel is situated in close proximity to the Forest of Dean, an ancient royal From the front of the house, there are views hunting forest. The Forest provides a accorss the lakes and over the hotel’s gardens wide variety of wildlife and activities, and grounds. including the Symonds Yat Rock, the The hotel is 0.8 miles from the A466 which International Centre for Birds of Prey, provides access south to Chepstow (8.5 Clearwell Caves and the Dean Forest miles) and north to Ross-on-Wye (17.5 Railway. -

Eisteddfod Genedlaethol Cymru - Cyfansoddiadau a Beirniadaethau (GB 0210 CYFANS)

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Cymorth chwilio | Finding Aid - Eisteddfod Genedlaethol Cymru - cyfansoddiadau a beirniadaethau (GB 0210 CYFANS) Cynhyrchir gan Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Argraffwyd: Mai 04, 2017 Printed: May 04, 2017 Wrth lunio'r disgrifiad hwn dilynwyd canllawiau ANW a seiliwyd ar ISAD(G) Ail Argraffiad; rheolau AACR2; ac LCSH Wrth lunio'r disgrifiad hwn dilynwyd canllawiau ANW a seiliwyd ar ISAD(G) Ail Argraffiad; rheolau AACR2; ac LCSH https://archifau.llyfrgell.cymru/index.php/eisteddfod-genedlaethol-cymru- cyfansoddiadau-beirniadaethau-2 archives.library .wales/index.php/eisteddfod-genedlaethol-cymru-cyfansoddiadau- beirniadaethau-2 Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Allt Penglais Aberystwyth Ceredigion United Kingdom SY23 3BU 01970 632 800 01970 615 709 [email protected] www.llgc.org.uk Eisteddfod Genedlaethol Cymru - cyfansoddiadau a beirniadaethau Tabl cynnwys | Table of contents Gwybodaeth grynodeb | Summary information .............................................................................................. 3 Hanes gweinyddol / Braslun bywgraffyddol | Administrative history | Biographical sketch ......................... 3 Natur a chynnwys | Scope and content .......................................................................................................... 4 Trefniant | Arrangement ................................................................................................................................. -

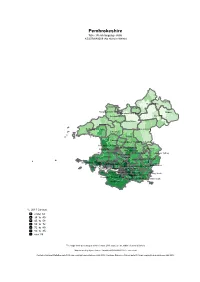

Pembrokeshire Table: Welsh Language Skills KS207WA0009 (No Skills in Welsh)

Pembrokeshire Table: Welsh language skills KS207WA0009 (No skills in Welsh) Cilgerran St. Dogmaels Goodwick Newport Fishguard North West Fishguard North East Clydau Scleddau Crymych Dinas Cross Llanrhian St. David's Solva Maenclochog Letterston Wiston Camrose Haverfordwest: Prendergast,Rudbaxton Haverfordwest: Garth Haverfordwest: Portfield Haverfordwest: Castle Narberth Martletwy Haverfordwest: Priory Narberth Rural Lampeter Velfrey Merlin's Bridge Johnston The Havens Llangwm Kilgetty/Begelly Amroth Milford: North Burton St. Ishmael's Neyland: West Milford: WestMilford: East Milford: Hakin Milford: Central Saundersfoot Milford: Hubberston Neyland: East East Williamston Pembroke Dock:Pembroke Market Dock: Central Carew Pembroke Dock: Pennar Penally Pembroke Dock: LlanionPembroke: Monkton Tenby: North Pembroke: St. MaryLamphey North Manorbier Pembroke: St. Mary South Pembroke: St. Michael Tenby: South Hundleton %, 2011 Census under 34 34 to 45 45 to 58 58 to 72 72 to 80 80 to 85 over 85 The maps show percentages within Census 2011 output areas, within electoral divisions Map created by Hywel Jones. Variables KS208WA0022−27 corrected Contains National Statistics data © Crown copyright and database right 2013; Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2013 Pembrokeshire Table: Welsh language skills KS207WA0010 (Can understand spoken Welsh only) St. Dogmaels Cilgerran Goodwick Newport Fishguard North East Fishguard North West Crymych Clydau Scleddau Dinas Cross Llanrhian St. David's Letterston Solva Maenclochog Haverfordwest: Prendergast,Rudbaxton Wiston Camrose Haverfordwest: Garth Haverfordwest: Castle Haverfordwest: Priory Narberth Haverfordwest: Portfield The Havens Lampeter Velfrey Merlin's Bridge Martletwy Narberth Rural Llangwm Johnston Kilgetty/Begelly St. Ishmael's Milford: North Burton Neyland: West East Williamston Amroth Milford: HubberstonMilford: HakinMilford: Neyland:East East Milford: West Saundersfoot Milford: CentralPembroke Dock:Pembroke Central Dock: Llanion Pembroke Dock: Market Penally LampheyPembroke:Carew St.