Welsh Tribal Law and Custom in the Middle Ages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Law and Constitution

Commission on Justice in Wales: Supplementary evidence of the Welsh Government to the Commission on Justice in Wales Contents Law and the Constitution 1 History and evolution 1 Problems operating Part 4 of the Government of Wales Act from 2011 onwards 4 Draft Wales Bill (2015) 7 Wales Act 2017 9 Accessibility of the law in Wales (and England) 10 Government and Laws in Wales Bill 12 Implications of creating a Welsh legal jurisdiction 15 Conclusion 18 Mae’r ddogfen yma hefyd ar gael yn Gymraeg. This document is also available in Welsh. © Crown copyright 2018 2 | Supplementary evidence of the WelshWG35635 Government Digital to ISBN the 978-1-78937-837-5 Commission on Justice in Wales Law and the Constitution 1. This paper is supplementary to the Welsh on designing a system of government that is the Government’s submission of 4 June 2018. most effective and produces the best outcomes for It focusses specifically on the law and the legal the people of Wales. Instead we have constitutional jurisdiction and its impact on government in Wales. arrangements which are often complex, confusing It also considers the potential impact of creating and incoherent. a Welsh legal jurisdiction and devolving the justice 5. One of the key junctures came in 2005 with system on the legal professions in Wales. the proposal to create what was to become a fully 2. The paper explores the incremental and fledged legislature for Wales. The advent of full piecemeal way in which Wales’ current system law making powers was a seminal moment and of devolved government has developed. -

THE RATIONAL STRENGTH of ENGLISH LAW AUSTRALIA the Law Book Co

THE RATIONAL STRENGTH OF ENGLISH LAW AUSTRALIA The Law Book Co. of Australasia Pty Ltd. Sydney : Melbourne : Brisbane CANADA AND U.S.A. The Carswell Company Limited Toronto INDIA N. M. Tripathi Limited Bombay NEW ZEALAND Legal Publications Ltd. Wellington THE HAMLYN LECTURES THIRD SERIES THE RATIONAL STRENGTH OF ENGLISH LAW BY F. H. LAWSON, D.c.L. of Gray's Inn, Barrister-at-Law, Professor of Comparative Law in the University of Oxford LONDON STEVENS & SONS LIMITED 1951 First published in 1951 by Stevens & Sons Limited of 119 <fe 120 Chancery IJine London - Law Publishers and printed in Great Britain by the Eastern Press Ltd. of London and Reading CONTENTS The Hamlyn Trust ..... page vii 1. SOURCES AND GENERAL CHARACTER OF THE LAW 3 2. CONTRACT ....... 41 3. PROPERTY 75 4. TORTS ........ 109 5. CONCLUSION ....... 143 HAMLYN LECTURERS 1949. The Right Hon. Sir Alfred Denning 1950. Richard O'Sullivan, K.C. 1951. F. H. Lawson, D.C.L. VI THE HAMLYN TRUST HE Hamlyn Trust came into existence under the will of the late Miss Emma Warburton THamlyn of Torquay, who died in 1941 aged 80. She came of an old and well-known Devon family. Her father, William Bussell Hamlyn, practised in Torquay as a solicitor for many years. She was a woman of dominant character, intelligent and cultured, well versed in literature, music, and art, and a lover of her country. She inherited a taste for law, and studied the subject. She travelled frequently on the Continent and about the Mediterranean and gathered impressions of comparative jurisprudence and ethnology. -

The Role and Importance of the Welsh Language in Wales's Cultural Independence Within the United Kingdom

The role and importance of the Welsh language in Wales’s cultural independence within the United Kingdom Sylvain Scaglia To cite this version: Sylvain Scaglia. The role and importance of the Welsh language in Wales’s cultural independence within the United Kingdom. Linguistics. 2012. dumas-00719099 HAL Id: dumas-00719099 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-00719099 Submitted on 19 Jul 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. UNIVERSITE DU SUD TOULON-VAR FACULTE DES LETTRES ET SCIENCES HUMAINES MASTER RECHERCHE : CIVILISATIONS CONTEMPORAINES ET COMPAREES ANNÉE 2011-2012, 1ère SESSION The role and importance of the Welsh language in Wales’s cultural independence within the United Kingdom Sylvain SCAGLIA Under the direction of Professor Gilles Leydier Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................. 1 WALES: NOT AN INDEPENDENT STATE, BUT AN INDEPENDENT NATION ........................................................ -

“English Law and Descent Into Complexity”

“ENGLISH LAW AND DESCENT INTO COMPLEXITY” GRAY’S INN READING BY LORD JUSTICE HADDON-CAVE Barnard’s Inn – 17th June 2021 ABSTRACT The Rule of Law requires that the law is simple, clear and accessible. Yet English law has in become increasingly more complex, unclear and inaccessible. As modern life becomes more complex and challenging, we should pause and reflect whether this increasingly complexity is the right direction and what it means for fairness and access to justice. This lecture examines the main areas of our legal system, legislation, procedure and judgments, and seeks to identify some of the causes of complexity and considers what scope there is for creating a better, simpler and brighter future for the law. Introduction 1. I am grateful to Gresham College for inviting me to give this year’s Gray’s Inn Reading.1 It is a privilege to follow a long line of distinguished speakers from our beloved Inn, most recently, Lord Carlisle QC who spoke last year on De-radicalisation – Illusion or Reality? 2. I would like to pay tribute to the work of Gresham College and in particular to the extraordinary resource that it makes available to us all in the form of 1,800 free public lectures available online stretching back nearly 40 years to Lord Scarman’s lecture Human Rights and the Democratic Process.2 For some of us who have not got out much recently, it has been a source of comfort and stimulation, in addition to trying to figure out the BBC series Line of Duty. 3. -

Welsh Government Summary of Events Following The

Public Accounts Committee - Additional Written Evidence Summary of events following the Statutory Inquiry at Tai Cantref The Statutory Inquiry report was completed in October 2015. The report found multiple instances of mismanagement and misconduct. The report made no comment beyond its brief to establish whether there was evidence to support the serious allegations made by whistle blowers. It made no recommendations or commentary on possible ways forward. Tai Cantref’s Board were given until 13th November 2015 to set out a credible response and plan to deal with the findings of the inquiry. The Welsh Government Regulation Team (the Regulator) considered that the initial response was inadequate in both the association’s acceptance of the findings and its intentions and commitment to tackling the issues raised. The Board was also required to share a copy of the Inquiry with its lenders who were similarly concerned with the response and reserved the right to enforce loan conditions. By this point an event of default had been triggered in Tai Cantref’s loan agreements. Following detailed discussions, including with lenders, the Board was given a second chance to respond to the findings. Shortly after this decision was notified to Tai Cantref, the Chair resigned and an existing Board member was unanimously appointed as the new Chair. The Board then took a number of key decisions which provided assurance it was now seeking to respond to the findings: the Board appointed a consultant to provide immediate support the Board to address the Inquiry findings. three suitably experienced, first language welsh speakers, were co- opted to strengthen the Board. -

IV. the Cantrefs of Morgannwg

; THE TRIBAL DIVISIONS OF WALES, 273 Garth Bryngi is Dewi's honourable hill, CHAP. And Trallwng Cynfyn above the meadows VIII. Llanfaes the lofty—no breath of war shall touch it, No host shall disturb the churchmen of Llywel.^si It may not be amiss to recall the fact that these posses- sions of St. David's brought here in the twelfth century, to re- side at Llandduw as Archdeacon of Brecon, a scholar of Penfro who did much to preserve for future ages the traditions of his adopted country. Giraldus will not admit the claim of any region in Wales to rival his beloved Dyfed, but he is nevertheless hearty in his commendation of the sheltered vales, the teeming rivers and the well-stocked pastures of Brycheiniog.^^^ IV. The Cantrefs of Morgannwg. The well-sunned plains which, from the mouth of the Tawe to that of the Wye, skirt the northern shore of the Bristol Channel enjoy a mild and genial climate and have from the earliest times been the seat of important settlements. Roman civilisation gained a firm foothold in the district, as may be seen from its remains at Cardiff, Caerleon and Caerwent. Monastic centres of the first rank were established here, at Llanilltud, Llancarfan and Llandaff, during the age of early Christian en- thusiasm. Politically, too, the region stood apart from the rest of South Wales, in virtue, it may be, of the strength of the old Silurian traditions, and it maintained, through many vicissitudes, its independence under its own princes until the eve of the Norman Conquest. -

English Contract Law: Your Word May Still Be Your Bond Oral Contracts Are Alive and Well – and Enforceable

Client Alert Litigation Client Alert Litigation March 13, 2014 English Contract Law: Your Word May Still be Your Bond Oral contracts are alive and well – and enforceable. By Raymond L. Sweigart American movie mogul Samuel Goldwyn is widely quoted as having said, ‘A verbal contract isn’t worth the paper it’s written on.’ He is also reputed to have stated, ‘I’m willing to admit that I may not always be right, but I am never wrong.’ With all due respect to Mr Goldwyn, he did not have this quite right and recent case law confirms he actually had it quite wrong. English law on oral contracts has remained essentially unchanged with a few exceptions for hundreds of years. Oral contracts most certainly exist, and they are certainly enforceable. Many who negotiate commercial contracts often assume that they are not bound unless and until the agreement is reduced to writing and signed by the parties. However, the courts in England are not at all reluctant to find that binding contracts have been made despite the lack of a final writing and signature. Indeed, as we have previously noted, even in the narrow area where written and signed contracts are required (for example pursuant to the Statute of Frauds requirement that contracts for the sale of land must be in writing), the courts can find the requisite writing and signature in an exchange of emails.1 As for oral contracts, a recent informative example is presented by the case of Rowena Williams (as executor of William Batters) v Gregory Jones (25 February 2014) reported on Lawtel reference LTL 7/3/2014 document number AC0140753. -

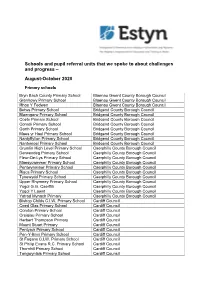

Schools and Pupil Referral Units That We Spoke to Autumn Term 2020

Schools and pupil referral units that we spoke to about challenges and progress – August-October 2020 Primary schools Bryn Bach County Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Glanhowy Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Rhos Y Fedwen Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Betws Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Blaengarw Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Coety Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Corneli Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Garth Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Maes yr Haul Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Nantyffyllon Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Nantymoel Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Crumlin High Level Primary School Caerphilly County Borough Council Derwendeg Primary School Caerphilly County Borough Council Fleur-De-Lys Primary School Caerphilly County Borough Council Maesycwmmer Primary School Caerphilly County Borough Council Pentwynmawr Primary School Caerphilly County Borough Council Risca Primary School Caerphilly County Borough Council Tynewydd Primary School Caerphilly County Borough Council Upper Rhymney Primary School Caerphilly County Borough Council Ysgol G.G. Caerffili Caerphilly County Borough Council Ysgol Y Lawnt Caerphilly County Borough Council Ystrad Mynach Primary Caerphilly County Borough Council Bishop Childs C.I.W. Primary School Cardiff Council Coed Glas Primary School Cardiff Council Coryton Primary School Cardiff Council Creigiau Primary School Cardiff Council Herbert Thompson Primary Cardiff Council Mount Stuart Primary Cardiff Council Pentyrch Primary School Cardiff Council Pen-Y-Bryn Primary School Cardiff Council St Fagans C.I.W. Primary School Cardiff Council St Philip Evans R.C. Primary School Cardiff Council Thornhill Primary School Cardiff Council Tongwynlais Primary School Cardiff Council Ysgol Gymraeg Treganna Cardiff Council Ysgol-Y-Wern Cardiff Council Brynamman Primary School Carmarthenshire County Council Cefneithin C.P. -

Why “Whiteland?” Why Exton?

Why “Whiteland?” Until 1765, East and West Whiteland Townships were a single township called Whiteland. Whiteland was the western edge of the Welsh Tract, an area of more than 40,000 acres that William Penn sold to an association of wealthy Welsh Quakers in 1684. One likely source of the name “Whiteland” is the Welsh village of “Whitland” – no “e” – in Carmarthenshire County. Settlements near Whitland include Haverford and Narberth, also the namesakes of towns in our region. Whitland was the site of the first Welsh parliament convened by Hywel the Good. According to Whitland’s website: “Hywel Dda was a Prince of Deheubarth, (the ancient region containing Whitland) who became eventual ruler of most of Wales through inheritance. He is noted in history as being responsible for codifying the laws of Wales, laws which stood for nearly 400 years until Henry VIII combined them with those of England. The “Dda” in Hywel's name means “good”, indeed his laws were considered forward thinking and fair, with emphasis on common sense and rights for women and compassion rather than punishment.” Another guess is that the name derived from the frequent views of fog in our valley. The Chester Valley (or Great Valley) is a prominent feature of both East and West Whiteland. When weather conditions are right, the valley is filled with fog and the land does indeed appear to be white. Why Exton? There also is no clear origin of the name “Exton.” Some claim it’s from the crossroads of Lincoln Highway and Pottstown Pike or from the “X” formed by the crossing of the former Chester Valley Railroad (now Chester Valley Trail) over Lincoln Highway, with one or both crossings inspiring “X-town” or Exton. -

WALES: RESISTANCE, CONQUEST and REBELLION C.1240-1415 THEME 1: Society, Culture and the Economy C.1240-1415

WALES: RESISTANCE, CONQUEST AND REBELLION c.1240-1415 THEME 1: Society, culture and the economy c.1240-1415 PART 1 - Chronology chart This is a suggested timeline for the theme covering society, culture and the economy c.1240-1415. The content coverage is derived from the specification. 1240-1284 1284-1360 1360-1415 Welsh laws and legal system under the native Statute of Rhuddlan1284 Changes to Welsh and Marcher Law Princes Marcher Law Poets, musicians and literature of the Welsh Edwardian castles and towns The Penal Laws 1402 Princes The rural economy and towns in Wales The treatment of the Welsh after conquest The effects of the Black Death on Wales The Church in Wales Bards, poets and story-telling in post- The rise of the gentry and the growth and conquest Wales management of estates PART 2 – a conceptual guide This provides a conceptual guide for the theme of society, culture and the economy c.1240-1415 which attempts to demonstrate how each concept underpins the period, how concepts are linked and the significance of these concepts. The aim is not to focus on the content of events but to provide appropriate guidance regarding historical concepts as appropriate. WALES: RESISTANCE, CONQUEST AND REBELLION c.1240-1415 THEME 1: Society, culture and the economy c.1240-1415 1240-1284 1284-1360 1360-1415 Cause and Consequence The Edwardian conquest of The treatment of the Welsh after The effects of the Black Death on Wales, 1282-1283 conquest Wales Society and the Glyndwr rebellion Significant individuals Llywelyn the Great Dafydd ap Gwilym -

Codification of Welsh Law Association of London Welsh Lawyers Lord Lloyd-Jones, Justice of the Supreme Court 8 March 2018

Codification of Welsh Law Association of London Welsh Lawyers Lord Lloyd-Jones, Justice of The Supreme Court 8 March 2018 I have been asked to say something about the context in which issue of the codification arises. I will identify the problem and Nicholas Paines QC and the Counsel General will then tell you how they propose to solve it. This is a very exciting time for the law in Wales. Since the acquisition by the National Assembly of primary law making powers under Part 4 of GOWA 2006, the extensive use made by the National Assembly of these powers means that for the first time since the age of the Tudors it has once again become meaningful to speak of Welsh law as a living system of law. As a result of this, and as a result of the corresponding development of Westminster legislating for England only, we are now witnessing a rapidly growing divergence between English law and Welsh law. At present this is particularly apparent in areas such as education, planning, social services and residential tenancies. No doubt, this divergence will accelerate and extend more broadly when the Wales Act 2017 – our fourth devolution settlement but the first on a reserved powers basis - comes into force shortly. The Law Commission is the Law Commission of England and Wales. From the start of devolution it has worked closely with the Welsh Government and the National Assembly. In the most recent phase of devolution in Wales, the Assembly has used its primary legislative powers to implement Law Commission recommendations. -

Schools and Pupil Referral Units That We Spoke to September

Schools and pupil referral units that we spoke to about challenges and progress – August-December 2020 Primary schools All Saints R.C. Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Blaen-Y-Cwm C.P. School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Bryn Bach County Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Coed -y- Garn Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Deighton Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Glanhowy Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Rhos Y Fedwen Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Sofrydd C.P. School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council St Illtyd's Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council St Mary's Roman Catholic - Brynmawr Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Willowtown Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Ysgol Bro Helyg Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Ystruth Primary Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Afon-Y-Felin Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Archdeacon John Lewis Bridgend County Borough Council Betws Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Blaengarw Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Brackla Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Bryncethin Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Bryntirion Infants School Bridgend County Borough Council Cefn Glas Infant School Bridgend County Borough Council Coety Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Corneli Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Cwmfelin Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Garth Primary School Bridgend