The Greenback Party in Maine, 1876-1884

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ideological Foundation of the People's Party of Texas Gavin Gray

1 The Ideological Foundation of the People’s Party of Texas Gavin Gray 2 Short lived insurgent third parties are a common feature in American political history, though few were as impactful as the nineteenth century People’s Party.1 Although the People’s Party itself faded out of existence after a few decades, the Republican and Democratic Parties eventually adopted much of their platform.2 In recent history Ross Perot and Donald Trump's appeals to economic nationalism is reminiscent of the old Populist platform. Since its inception, the ideological foundation of the People's Party has remained a point of contention among historians. Traditional historiography on the People's Party, which included figures such as Frederick Jackson Turner and Richard Hofstadter, described it as a conservative movement rooted in agrarian Jacksonianism. In 1931 John Hicks' The Populist Revolt presented the new perspective that the People's Party, far from being conservative, was the precursor to the twentieth century Progressive movement. For the purpose of this study I focused exclusively on the ideological foundation of the People’s Party as it existed within the state of Texas. The study focused exclusively on the People’s Party within Texas for two reasons. The first reason is because the People’s Party organized itself on a statewide basis. The nationwide People’s Party operated as a confederation, each state party had its own independent structure and organizational history, therefore each state party itself must be studied independently.3 The second reason is because one of the People’s Party’s immediate predecessors, the Southern Farmers’ Alliance, had its roots in Texas.4 If one is attempting to study the origins of the People’s Party, then one must examine it where its roots are oldest. -

Committee on Appropriations UNITED STATES SENATE 135Th Anniversary

107th Congress, 2d Session Document No. 13 Committee on Appropriations UNITED STATES SENATE 135th Anniversary 1867–2002 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2002 ‘‘The legislative control of the purse is the central pil- lar—the central pillar—upon which the constitutional temple of checks and balances and separation of powers rests, and if that pillar is shaken, the temple will fall. It is...central to the fundamental liberty of the Amer- ican people.’’ Senator Robert C. Byrd, Chairman Senate Appropriations Committee United States Senate Committee on Appropriations ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia, TED STEVENS, Alaska, Ranking Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi ANIEL NOUYE Hawaii D K. I , ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania RNEST OLLINGS South Carolina E F. H , PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico ATRICK EAHY Vermont P J. L , CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri OM ARKIN Iowa T H , MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky ARBARA IKULSKI Maryland B A. M , CONRAD BURNS, Montana ARRY EID Nevada H R , RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama ERB OHL Wisconsin H K , JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire ATTY URRAY Washington P M , ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah YRON ORGAN North Dakota B L. D , BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado IANNE EINSTEIN California D F , LARRY CRAIG, Idaho ICHARD URBIN Illinois R J. D , KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas IM OHNSON South Dakota T J , MIKE DEWINE, Ohio MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana JACK REED, Rhode Island TERRENCE E. SAUVAIN, Staff Director CHARLES KIEFFER, Deputy Staff Director STEVEN J. CORTESE, Minority Staff Director V Subcommittee Membership, One Hundred Seventh Congress Senator Byrd, as chairman of the Committee, and Senator Stevens, as ranking minority member of the Committee, are ex officio members of all subcommit- tees of which they are not regular members. -

Saturday, March 04, 1893

.._ I I CONGRESSIONAL ; PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES QF THE FIUY-THIRD CONGRESS. SPECIAL SESSION OF THE SENATE. - ' SEN.ATE. ADDRESS OF THE VICE-ERESIDENT. The VICE-PRESIDENT. Senators, 'tleeply impressed with a S.A.TURlY.A.Y, Ma.rch 4, 1893. sense of its responsibilities and of its dignities, I now enter upon Hon. ADLAI E. STEVENSON, Vice-President _of the United the discharge of the duties of the high office to wJ:lich I have States, having taken the oath of office at the close of the last been called. regular session of the Fifty-second Congress, took the Qhair. I am not unmindful of the fact that among the occupants of this chair during the one hundred and four years of our consti PRAYER. tutional history have been statesmen eminent alike for their tal Rev. J. G. BUTLER, D. D., Chaplain to the Senate, offered the ents and for their tireless devotion to public duty. Adams, Jef following prayer: ferson, and Calhoun honored its incumbency during the early 0 Thou, with whom is no variableness or shadow of turning, days of the Republic, while Arthur, Hendricks, and Morton the unchangeable God, whose throne stands forever, and whose have at a later period of our history shed lust.er upon the office dominion ruleth over all; we seek a Father's blessing as we wait of President of the most august deliberatiVe assembly known to at the mercy seat. We bring to Thee our heart homage, God of men. our fathers, thanking Thee fqr our rich heritage of faith and of I assums the duties of the great trust confided to me with no freedom, hallowed bv the toils and tears, the valor and blood feeling of self-confidence, but rather with that of grave distrust and prayers, of our patriotdead. -

Efforts to Establish a Labor Party I!7 America

Efforts to establish a labor party in America Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors O'Brien, Dorothy Margaret, 1917- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 01/10/2021 15:33:37 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/553636 EFFORTS TO ESTABLISH A LABOR PARTY I!7 AMERICA by Dorothy SU 0s Brlen A Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Department of Economics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate College University of Arizona 1943 Approved 3T-:- ' t .A\% . :.y- wissife mk- j" •:-i .»,- , g r ■ •: : # ■ s &???/ S 9^ 3 PREFACE The labor movement In America has followed two courses, one, economic unionism, the other, political activity* Union ism preceded labor parties by a few years, but developed dif ferently from political parties* Unionism became crystallized in the American Federation of Labor, the Railway Brotherhoods and the Congress of Industrial Organization* The membership of these unions has fluctuated with the changes in economic conditions, but in the long run they have grown and increased their strength* Political parties have only arisen when there was drastic need for a change* Labor would rally around lead ers, regardless of their party aflliations, -

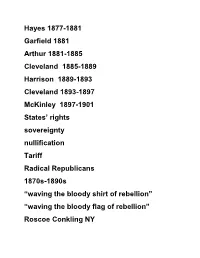

List for 202 First Exam

Hayes 1877-1881 Garfield 1881 Arthur 1881-1885 Cleveland 1885-1889 Harrison 1889-1893 Cleveland 1893-1897 McKinley 1897-1901 States’ rights sovereignty nullification Tariff Radical Republicans 1870s-1890s “waving the bloody shirt of rebellion” “waving the bloody flag of rebellion” Roscoe Conkling NY James G. Blaine Maine “Millionnaires’ Club” “the Railroad Lobby” 1. Conservative Rep party in control 2. Economy fluctuates a. Poor economy, prosperity, depression b. 1873 1893 1907 1929 c. Significant technological advances 3. Significant social changes 1876 Disputed Election of 1876 Rep- Rutherford B. Hayes Ohio Dem-Samuel Tilden NY To win 185 Tilden 184 + 1 Hayes 165 + 20 Fl SC La Oreg January 1877 Electoral Commission of 15 5 H, 5S, 5SC 7 R, 7 D, 1LR 8 to 7 Compromise of 1877 1. End reconstruction April 30, 1877 2. Appt s. Dem. Cab David Key PG 3. Support funds for internal improvements in the South Hayes 1877-1881 “ole 8 and 7 Hayes” “His Fraudulency” Carl Schurz Wm Everts Civil Service Reform Chester A. Arthur Great Strike of 1877 Resumption Act 1875 specie Bland Allison Silver Purchase Act 1878 16:1 $2-4 million/mo Silver certificates 1880 James G. Blaine Blaine Halfbreeds Rep James A Garfield Ohio Chester A. Arthur Roscoe Conkling Conkling Stalwarts Grant Dem Winfield Scott Hancock PA Greenback Party James B. Weaver Iowa Battle of the 3 Generals 1881 Arthur Pendleton Civil Service Act 1883 Chicago and Boston 1884 Election Rep. Blaine of Maine Mugwumps Dem. Grover Cleveland NY “Rum, Romanism and Rebellion” 1885-1889 Character Union Veterans Grand Army of the Republic GAR LQC Lamar S of Interior 1862 union pension 1887 Dependent Pension Bill Interstate Commerce Act 1887 ICC Pooling, rebates, drawbacks Prohibit discrimination John D. -

Colby Alumnus Vol. 34, No. 5: March 1945

Colby College Digital Commons @ Colby Colby Alumnus Colby College Archives 1945 Colby Alumnus Vol. 34, No. 5: March 1945 Colby College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/alumnus Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Colby College, "Colby Alumnus Vol. 34, No. 5: March 1945" (1945). Colby Alumnus. 279. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/alumnus/279 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the Colby College Archives at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Alumnus by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Colby. "HE COLBY 0 !lRCH_, 1945 ALUMNUS COLBY ON TO VICTORY R. J. PEACOCK CAN NING CASCADE WOOL EN MILL COMPANY Oakland, Maine Lubec Maine Manufacturers of Canners of WOO LENS MAINE SARDINES The Wa terville Morning Sentinel is the paper ca rrying the most news of Colby Col •••COFFEE, JHAT GRACES . THE TABLES 6F AMERICA1S lege. If you want to keep FINEST EATING PLACES- SE XTON 'S in touch with your boys, HO TEL read the SENTINEL. BLEN D SEXTON'S QUAl/TY FOODS .fl <JJiAeetOlUJ � 3'4iendfif 9iJuM Compliments of Premier Brand Groceries Compliments of ALWAYS TOPS Charles H. Vigue Proctor and I Ask Your Grocer BUILDING MA TERIAL If not in stock write Bowie Co. J. T. ARCHAMBEAU l Bay Street 61 Halifax Street Portland, Maine WINSLOW MAINE I will get you Premier goods WINSLOW : : MAINE Compliments of Compliments of Tileston & THE PIE PLATE Harold W. Hollingsworth Co. 213 Congress St., Boston, Mass. CHESTER DUNLAP, Mgr. PAPERMAKERS Upper College Avenue Kimball Co. -

Congressional Record-8Enate. .7175

1914. CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-8ENATE. .7175 By l\fr. WEBB: Petition of sundry citizens of Catawba, Gas The proceedings referred to are as follows: ton, Union, Wayne, and Ramseur Counties, all in the State of PROCEEDINGS AT THE UNVEILING OF THE STATUE OF ZAClllRIAR North Carolina, favoring national prohibition; to the Commitree CHANDLER, STA'J.'UARY HALL, UNITED STATES CAPITOL, MONDAY, .Tt:iNE on the Judiciary. ~0, 1913, 11 O'CLOCK A. M. By Mr. WILLIAMS: Petition of 7,000 citizens of congressional Senator WILLIAM ALDEN SMITH, of Michigan (chairman}. districts 1 to 10 of the State of Illinois, ..;;>rotesting against The service which we have met here to perform will be opened nation-wide prohibition; to the Committee on the Judiciary. with prayer by the Rev. Henry N. Couden, D. D., of Port Huron, By Mr. WILLIS: Petition of the National Automobile Cham Mich., Chaplain of the House of Representatives. ber of Commerce, of New York City, against the interstate t-rade commission bill; to the Committee on Interstate and Fo:- OPENING PRAYER. ei rn Commerce. The Chaplain of the House of Representatives, Rev. Henry .A lso, petition of Frank HUff and 4 other citizens of Findlay, N. Coud€n, D. D., offered the following prayer: Ohio, against national prohibition; to the Oommittee on the Great God, our King and our Father, whose spirit penades Judiciary. all spn.ee with rays divine, a \ery potent factor in shaping and By Mr. WILSON of New York: Petition of the United Socie guiding the progress of men and of nations ·::hrough all the ties for Local Self-Government of Chicago, Ill., and dtizens of vicissitudes of the past, we rejoice that the long struggle for N'ew York, agrunst national prohibition; to the Committee on civil, political, and religious rights culminated in a Nation the .Judiciary. -

Uniting Mugwumps and the Masses: the Role of Puck in Gilded Age Politics, 1880-1884

Uniting Mugwumps and the Masses: The Role of Puck in Gilded Age Politics, 1880-1884 Daniel Henry Backer McLean, Virginia B.A., University of Notre Dame, 1994 A Thesis presented to 1he Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of English University of Virginia August 1996 WARNING! The document you now hold in your hands is a feeble reproduction of an experiment in hypertext. In the waning years of the twentieth century, a crude network of computerized information centers formed a system called the Internet; one particular format of data retrieval combined text and digital images and was known as the World Wide Web. This particular project was designed for viewing through Netscape 2.0. It can be found at http://xroads.virginia.edu/~MA96/PUCK/ If you are able to locate this Website, you will soon realize it is a superior resource for the presentation of such a highly visual magazine as Puck. 11 Table of Contents Introduction 1 I) A Brief History of Cartoons 5 II) Popular and Elite Political Culture 13 III) A Popular Medium 22 "Our National Dog Show" 32 "Inspecting the Democratic Curiosity Shop" 35 Caricature and the Carte-de-Viste 40 The Campaign Against Grant 42 EndNotes 51 Bibliography 54 1 wWhy can the United States not have a comic paper of its own?" enquired E.L. Godkin of The Nation, one of the most distinguished intellectual magazines of the Gilded Age. America claimed a host of popular and insightful raconteurs as its own, from Petroleum V. -

The Story Behind the Garcelon Mansion by David C

Published quarterly by the Lovell Historical Society Volume 17, Number 4 Fall 2010 The Garcelon Family in front of their home on Kezar Lake. Photo donated by David C. Gareelon The Story Behind the Garcelon Mansion By David C. Garcelon At the north end of Kezar Lake sits a magnificent neoclassical style home known as the "Garcelon Mansion". Built for Charles Augustus Garcelon and his family in 1908 and 1909, the house commands magnificent views ofthe White Mountains and is unequalled in the quality of its design. Constructed by Italian craftsmen, the house features maple floors, hand-carved paneling and an elaborate staircase framed by columns. This is the story ofhow this home came to be built. Charles Garcelon was born in Lewiston on November 14, 1842. He was the son of Dr. Alonzo and Ann Augusta (Waldron) Garce10n and the great-great-grandson ofJames and Deliverance (Annis) Garcelon, who were among the first settlers in 1776 of Lewiston Falls, an Indian garrison on the Androscoggin River. The family's imprint on the area exists to this day. The Garcelons were farmers. They were also very much involved in the development ofLewiston and its sUlTounding area. From the time Charles was born in 1842, until he left for the Civil War in 1862, he was at the center of a family which was not only known for having the finest horses, growing the largest cabbages and having the best orchards, but who also started the Lewiston Falls Journal. The family was instrumental in (continued on pagc 3) .' From the President This year has been very busy with renovations The to the Kimball-Stanford House, fund-raising events, wonderful additions to our collection, new members Fall Harvest and research volunteers. -

Portland Daily Press: February 03,1882

PORTLAND DAILY PRESS. ESTABLISHED JUNE 23, I862.-TOL. 10. WEDNESDAY PORTLAND, MORNING, JUNE 4, 1879. TERMS $8.00 PEE ANNUM, dTaDYANCe” jiil IVIHLAKD DAILY TRESS, CITY ADVERTISEMENTS. who in the Rebellion of Published every day (Sundays excepted) by the INSURANCE. fought their just Memorial MISCELLANEOUS.__ ___ THE PRES8. Striking Address. I_ and equal share and inlluence in tho Gov- PORTLAND FVBLISSISIVG CO., CITY OF PORTLAND. but I do insist that the At 109 WEDNESDAY ernment; people who Exchange St., Portland. MORNING, JUNE 4. Wendell Phlliip3 on the Lessons of The Drains and Sewers to still hold to a doctrine which is subversive Terms : Eight Dollars a Year. To mail subscrib- Build. ers I of all which from tho Day. Seven Dollars a if in advance. FREE I AVe do not read government, it Year, paid TICKETS anonymous letters and communi- day will be received tlie Com- Proposals by was first in SEALEDmittee on Drains and Sewers till MONDAY, cations. 1 he name and address of the writer are in conceived, was itself incipient THE MAINeTsTATE TRESS the 9th at 12 o’clock hist., noon, for building Sew- TO all cases indispensable, not necessarily for publica- treason, which has desolated The following is the memorial address de- is ers in Elm, Congress, West Commer- nearly every published every Thursday Morning at $2.50 a Cumberland, tion but as a of faith. livered cial and North to aud guaranty good household in the shall no by Wendell Decoration year, if paid in advance at $2.00 a year. Streets, according plaus speci- land, have more Phillips, Day fications at City Civil Engineer's office. -

Catalogue of the Athenaean Society of Bowdoin College

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Maine History Documents Special Collections 1844 Catalogue of the Athenaean Society of Bowdoin College Athenaean Society (Bowdoin College) Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistory Part of the History Commons This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine History Documents by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pamp 285 CATALOGUE OF THE ATHENANE SOCIETY BOWDOIN COLLEGE. INSTITUTED M DCCC XVII~~~INCORFORATED M DCCC XXVIII. BRUNSWICK: PRESS OF JOSEPH GRIFFIN. 1844. RAYMOND H. FOGLER LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MAINE ORONO, MAINE from Library Number, OFFICERS OF THE GENERAL SOCIETY. Presidents. 1818 LEVI STOWELL . 1820 1820 JAMES LORING CHILD . 1821 1821 *WILLIAM KING PORTER . 1822 1822 EDWARD EMERSON BOURNE . 1823 1823 EDMUND THEODORE BRIDGE . 1825 1825 JAMES M’KEEN .... 1828 1828 JAMES LORING CHILD . 1829 1829 JAMES M’KEEN .... 1830 1830 WILLIAM PITT FESSENDEN . 1833 1833 PATRICK HENRY GREENLEAF . 1835 1835 *MOSES EMERY WOODMAN . 1837 1837 PHINEHAS BARNES . 1839 1839 WILLIAM HENRY ALLEN . 1841 1841 HENRY BOYNTON SMITH . 1842 1842 DANIEL RAYNES GOODWIN * Deceased. 4 OFFICERS OF THE Vice Presidents. 1821 EDWARD EMERSON BOURNE . 1822 1822 EDMUND THEODORE BRIDGE. 1823 1823 JOSIAH HILTON HOBBS . 1824 1824 ISRAEL WILDES BOURNE . 1825 1825 CHARLES RICHARD PORTER . 1827 1827 EBENEZER FURBUSH DEANE . 1828 In 1828 this office was abolished. Corresponding Secretaries. 1818 CHARLES RICHARD PORTER . 1823 1823 SYLVANUS WATERMAN ROBINSON . 1827 1827 *MOSES EMERY WOODMAN . 1828 In 1828 this office was united with that of the Recording Secretary. -

Portland Daily Press: November 13, 1876

ESTABLISHED JUKE 23, 1862.-VOL. MONDAY MORNING, NOVEMBER 13, 1876. TERMS $8.00 PER ANNUM, IN H.___PORTLAND, _ ADYAM^ ENTERTAINMENTS. ENTERTAINMENTS. business cards. mous figure of The for 257/000. average dail f President and Vice-President. This __MISCELLANEOUS._ THE PRESS- bill = attendance for September was 82,000, fo was referred to tbe Committee of Privileges THE and Elections. It was roported back October 00,000, for November O 1 amended Monday evening,Nov. 13tli, T. e. MONDAY 1876 100,000. and after much the Maine Charitable Mechanics’ As HARE TIMES REED, MORNING, NOV. 13. debate, passed 24th of Friday 170,000 paying visitors wil March, 1875, by a vote of 32 yeas to 26 nays, sedation ■ ■ nessed Congressional RECEPTION HALL. We do not read the closing ceremonies. Th i 1“®? Kecord, pp. 1662, 1674, lyoo, AND Counsellor at Law I anonymous letters and communi- 1!)36, 3 {1-15 for a cations. The total J having completed arrangements name and address of the writer are In paying admissions have been ove Oq the of has to day its passage Mr. Thurman, removed all eases not Indispensable, necessarily lor publication 8,000,000, and the receipts at the turnstile 5 ba(l voted for it, moved a reconsideration, Free Course of Lectures but as a of faith. -Lhis was a^3VEF^IG-PT Rooms a and. 3, guaranty good over $3,810,000. The amount received fron debated at different times, but do PRICES We cannot undertake nnal action was announce that the course will lie opened on to return or reserve commu- bad on tbe bill, and it is now MRS.