A Descriptive Grammar of Merei (Vanuatu) Pacific Linguistics 573

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

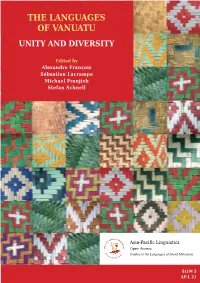

The Languages of Vanuatu: Unity and Diversity Alexandre François, Sébastien Lacrampe, Michael Franjieh, Stefan Schnell

The Languages of Vanuatu: Unity and Diversity Alexandre François, Sébastien Lacrampe, Michael Franjieh, Stefan Schnell To cite this version: Alexandre François, Sébastien Lacrampe, Michael Franjieh, Stefan Schnell. The Languages of Vanu- atu: Unity and Diversity. Alexandre François; Sébastien Lacrampe; Michael Franjieh; Stefan Schnell. France. 5, Asia Pacific Linguistics Open Access, 2015, Studies in the Languages of Island Melanesia, 9781922185235. halshs-01186004 HAL Id: halshs-01186004 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01186004 Submitted on 23 Aug 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License THE LANGUAGES OF VANUATU UNITY AND DIVERSITY Edited by Alexandre François Sébastien Lacrampe Michael Franjieh Stefan Schnell uages o ang f Is L la e nd h t M in e l a Asia-Pacific Linguistics s e n i e ng ge of I d a u a s l L s and the M ni e l a s e s n i e d i u s t a S ~ ~ A s es ia- c P A c u acfi n i i c O pe L n s i g ius itc a -

Library of Congress Subject Headings for the Pacific Islands

Library of Congress Subject Headings for the Pacific Islands First compiled by Nancy Sack and Gwen Sinclair Updated by Nancy Sack Current to January 2020 Library of Congress Subject Headings for the Pacific Islands Background An inquiry from a librarian in Micronesia about how to identify subject headings for the Pacific islands highlighted the need for a list of authorized Library of Congress subject headings that are uniquely relevant to the Pacific islands or that are important to the social, economic, or cultural life of the islands. We reasoned that compiling all of the existing subject headings would reveal the extent to which additional subjects may need to be established or updated and we wish to encourage librarians in the Pacific area to contribute new and changed subject headings through the Hawai‘i/Pacific subject headings funnel, coordinated at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.. We captured headings developed for the Pacific, including those for ethnic groups, World War II battles, languages, literatures, place names, traditional religions, etc. Headings for subjects important to the politics, economy, social life, and culture of the Pacific region, such as agricultural products and cultural sites, were also included. Scope Topics related to Australia, New Zealand, and Hawai‘i would predominate in our compilation had they been included. Accordingly, we focused on the Pacific islands in Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia (excluding Hawai‘i and New Zealand). Island groups in other parts of the Pacific were also excluded. References to broader or related terms having no connection with the Pacific were not included. Overview This compilation is modeled on similar publications such as Music Subject Headings: Compiled from Library of Congress Subject Headings and Library of Congress Subject Headings in Jewish Studies. -

Francois Et Al. -- the Languages of Vanuatu: Unity and Diversity

THE LANGUAGES OF VANUATU UNITY AND DIVERSITY Edited by Alexandre François Sébastien Lacrampe Michael Franjieh Stefan Schnell uages o ang f Is L la e nd h t M in e l a Asia-Pacific Linguistics s e n i e ng ge of I d a u a s l L s and the M ni e l a s e s n i e d i u s t a S ~ ~ A s es ia- c P A c u acfi n i i c O pe L n s i g ius itc a t S ~ Open Access ~ A s s s i e a c -P c a A Studies in the Languages of Island Melanesia ci n fic pe Linguistics O SLIM 5 AP-L 21 7KHODQJXDJHVRI9DQXDWX8QLW\DQGGLYHUVLW\ edited by $OH[DQGUH)UDQ©RLV6«EDVWLHQ/DFUDPSH0LFKDHO)UDQMLHK6WHIDQ6FKQHOO :LWKDQHVWLPDWHGGLIIHUHQWLQGLJHQRXVODQJXDJHV9DQXDWXLVWKHFRXQWU\ ZLWK WKH KLJKHVW OLQJXLVWLF GHQVLW\ LQ WKH ZRUOG :KLOH WKH\ DOO EHORQJ WR WKH 2FHDQLFIDPLO\WKHVHODQJXDJHVKDYHHYROYHGLQWKUHHPLOOHQQLDIURPZKDWZDV RQFH D XQLILHG GLDOHFW QHWZRUN WR WKH PRVDLF RI GLIIHUHQW ODQJXDJHV WKDW ZH NQRZ WRGD\ ,Q WKLV UHVSHFW 9DQXDWX FRQVWLWXWHV D YDOXDEOH ODERUDWRU\ IRU H[SORULQJWKHZD\VLQZKLFKOLQJXLVWLFGLYHUVLW\FDQHPHUJHRXWRIIRUPHUXQLW\ 7KLV YROXPH UHSUHVHQWV WKH ILUVW FROOHFWLYH ERRN GHGLFDWHG VROHO\ WR WKH ODQJXDJHVRIWKLVDUFKLSHODJRDQGWRWKHYDULRXVIRUPVWDNHQE\WKHLUGLYHUVLW\ ,WVWHQFKDSWHUVFRYHUDZLGHUDQJHRIWRSLFVLQFOXGLQJYHUEDODVSHFWYDOHQF\ SRVVHVVLYH VWUXFWXUHV QXPHUDOV VSDFH V\VWHPV RUDO KLVWRU\ DQG QDUUDWLYHV The languages of Vanuatu: Unity and DiversitySURYLGHVQHZLQVLJKWVRQWRWKH VULFKOLQJXLVWLFODQGVFDSHڙPDQ\IDFHWVRI9DQXDWX Cover design: +DQQDK5¸GGH )ROORZLQJWKHSULQFLSOHVRIAsia–Pacific LinguisticsSXEOLFDWLRQVDOOWKHDUWLFOHVLQWKH SUHVHQWYROXPHKDYHIROORZHGDVWULFWSURFHVVRIGRXEOHEOLQGSHHUUHYLHZLQJ -

Title Tutuba Texts : 'A Bush Sprite and a Good Man'

Tutuba Texts : 'A Bush Sprite and a Good Man', and 'Two Bush Title Sprites and Two Little Boys' Author(s) Naitou, Maho Citation Dynamis : ことばと文化 (2004), 8: 127-148 Issue Date 2004-10-15 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/87709 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University DYNAMIS, 8 (2004) , 127-148 Tutuba Texts —‘A Bush Sprite and a Good Man’ , and ‘Two Bush Sprites and Two Little Boys’— Maho Naitou 1. Introduction Tutuba language is spoken as the traditional language of Tutuba islands, Vanu- atu. An Oceanic language, it is spoken as a first language by approximately 500' people (Lynch and Crowley 2001 p47.). The phonemes of Tutuba are: /b t d k m n xj j3 s h r l (b) (m); i e a o u/. /(b) (m)/ are pronounced by the older (more than 50) and now young generation pronounce /b m/ instead. Voicedstops are prenasalized. This is mostly noticeable in non-utterance-initial position as well as other Oceanic languages. The following two texts are in the Tutuba language, and narrated by Turambue (male, 70's), who was born and raised in Tutuba. They are folktales about the bush sprites who have long hair, long nails and can fly2. I translate these texts into both English and Japanese3. Abbreviation in glosses and Orthography are shown in page 147. 2. Texts The following two stories were recorded on 15 August 2004 in Feoa village. 1There are several reports about the number of Tutuba language speakers. For exam- ple, Lynch and Crowley (2001 p47.) reports that the number of the speakers is 500, and SIL(http://www.ethnologue.com/ 2004. -

Greville G. Corbett (Ed.) the Expression of Gender the Expression of Cognitive Categories

Greville G. Corbett (Ed.) The Expression of Gender The Expression of Cognitive Categories Editors Wolfgang Klein Stephen Levinson Volume 6 The Expression of Gender Edited by Greville G. Corbett ISBN: 978-3-11-030660-6 e-ISBN: 978-3-11-030733-7 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2014 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Typesetting: PTP-Berlin Protago-TEX-Production GmbH, Berlin Printing: Hubert & Co. GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Contents Greville G. Corbett Introduction 1 Sally McConnell-Ginet Gender and its relation to sex: The myth of ‘natural’ gender 3 Michael Dunn Gender determined dialect variation 39 Peter Hegarty Ladies and gentlemen: Word order and gender in English 69 Greville G. Corbett Gender typology 87 Marianne Mithun Gender and culture 131 Niels O. Schiller Psycholinguistic approaches to the investigation of grammatical gender 161 Mulugeta T. Tsegaye, Maarten Mous and Niels O. Schiller Plural as a value of Cushitic gender: Evidence from gender congruency effect experiments in Konso (Cushitic) 191 Author index 215 Language index 219 Subject index 221 Greville G. Corbett Introduction Gender is an endlessly fascinating category. It has obvious links to the real world, first in the connection between many grammatical gender systems and biologi- cal sex, and second in other types of categorization such as size, which underpin particular gender systems and also have external correlates. -

Languages of Vanuatu a New Survey and Bibliography

Languages of Vanuatu A new survey and bibliography Lynch, J. and Crowley, T. Languages of Vanuatu: A new survey and bibliography. PL-517, xiv + 187 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 2001. DOI:10.15144/PL-517.cover ©2001 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. Also in PacificLinguistics Lois Carrington, 1996, A linguistic bibliography of the New Guinea area. Lois Carrington and Geraldine Triffitt, 1999, OZBIB: a linguistic bibliography of Aboriginal Australia and the Torres Strait Islands. Ross Clark, 1998, A dictionary of the Mele language (Atara Imere), Vanuatu. Terry Crowley, 1999, Ura: a disappearing language of southern Vanuatu. Terry Crowley, 2000, An Erromangan (Sye) dictionary. John Lynch, 2000, A grammar of Anejom. John Lynch, 2001, The linguistic history of southern Vanuatu. John Lynch and Philip Tepahae, 2001, Anejom dictionary Diksonari blong Anejom / / Nitasviitai a nijitas antas Anejom. Pacific Linguistics is a publisher specialising in grammars and linguistic descriptions, dictionaries and other materials on languages of the Pacific, the Philippines, Indonesia, Southeast and South Asia, and Australia. Pacific Linguistics, established in 1963 through an initial grant from the Hunter Douglas Fund, is associated with the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies at The Australian National University. The Editorial Board of Pacific Linguistics is made up of the academic staff of the School's Department of Linguistics. The authors and editors of Pacific Linguistics publications are drawn from a wide range of institutions around the world. Publications are refereed by scholars with relevant expertise who are usually not members of the editorial board. -

LCSH Section V

V (Fictitious character) (Not Subd Geog) V2 Class (Steam locomotives) Vaca Basin UF Ryan, Valerie (Fictitious character) USE Class V2 (Steam locomotives) BT Submarine topography—Mexico, Gulf of Valerie Ryan (Fictitious character) V838 Mon (Astronomy) Vaca de Vega family (Not Subd Geog) V-1 bomb (Not Subd Geog) USE V838 Monocerotis (Astronomy) Vaca family UF Buzz bomb V838 Monocerotis (Astronomy) USE Baca family Flying bomb This heading is not valid for use as a geographic Vaca Island (Haiti) FZG-76 (Bomb) subdivision. USE Vache Island (Haiti) Revenge Weapon One UF V838 Mon (Astronomy) Vaca Muerta Formation (Argentina) Robot bombs Variable star V838 Monocerotis BT Formations (Geology)—Argentina V-1 rocket BT Variable stars Geology, Stratigraphic—Cretaceous Vergeltungswaffe Eins V1343 Aquilae (Astronomy) Geology, Stratigraphic—Jurassic BT Surface-to-surface missiles USE SS433 (Astronomy) Vacada Rockshelter (Spain) NT A-5 rocket Va (Asian people) UF Abrigo de La Vacada (Spain) Fieseler Fi 103R (Piloted flying bomb) USE Wa (Asian people) BT Caves—Spain V-1 rocket VA hospitals Spain—Antiquities USE V-1 bomb USE Veterans' hospitals—United States Vacamwe (African people) V-2 bomb Va language USE Kamwe (African people) USE V-2 rocket USE En language Vacamwe language V-2 rocket (Not Subd Geog) VA mycorrhizas USE Kamwe language UF A-4 rocket USE Vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizas Vacanas Revenge Weapon Two Va Ngangela (African people) USE Epigrams, Kannada Robot bombs USE Ngangela (African people) Vacancy of the Holy See V-2 bomb Vaaga family UF Popes—Vacancy -

日本地理言語学会第2回大会予稿集 Proceedings of the Second Annual

日本地理言語学会第2回大会予稿集 Proceedings of the Second Annual Meeting of the Geolinguistic Society of Japan 2020 年 9 月 27 日 27th September, 2020 オンライン Online 日本地理言語学会第二回大会プログラム 日時:2020年9月27日(日) オンラインによる一日開催 参加費:無料 〇本会は会員制度をとっておりませんので、どなたでも参加できます。 〇Zoomを利用して開催します。発表者・司会者と聴講を希望される方は以下のURLで、参加申し込みを お願いします。折り返し、ZoomのURLをお知らせします。 https://forms.gle/AA5uopHegL5Jeptr8 〇研究発表スケジュール: 9月27日(日) 以下、日本時間 900-1030 司会: 福嶋秩子(新潟県立大学) 1.語境界線(isogloss)から観察するアラビア語諸方言の様相 長渡陽一(東京外国語大学特別研究員) 2. 東南アジア大陸部諸語における発声類型の地理分布 倉部慶太(東京外国語大学アジア・アフリカ言語文化研究所) 3. 横浜ドイツ人学校におけるドイツ語の方言接触-綴り<s>におけるスピーチ・アコモデーション- 金田懐子(東京大学)・松本和子(東京大学) 1045-1145 司会: 岸江信介(奈良大学) 4. サハリンの朝鮮語話者コミュニティーにおける方言・言語接触 ‐ 音節核のヴァリエーションに関 する事例研究 ‐ 吉田さち (跡見学園女子大学)・松本和子 (東京大学) 5. 計量的分析における統語関係を反映させた変数及び行列設定の試み –ロマンシュ語の否定を例に– 清宮貴雅(東京外国語大学博士後期課程) 1145-1300 昼休憩 1300-1430 Chair: Ray Iwata (Komatsu University) 6. Disappearing overcounting numeral systems in the Luzon–Taiwan area Izumi Ochiai (Hokkaido University) 7. Mapping the Case Systems among Kuki-Chin-Naga Languages in Northeast India MURAKAMI Takenori (Kyoto University) 8. Geolinguistic significance of the Phongpa dialect in the history of Yunnan Tibetan Hiroyuki SUZUKI (Fudan University) 1445-1545 Chair: Mitsuaki Endo (Aoyama Gakuin University) 9. A Geolinguistic Survey of Jianyin and Tuanyin in Rizhao dialect of Chinese Qi Haifeng (Shanghai International Studies University) 10. 最近隣法による文字変異の地図化と語彙拡散の計量化 古スペイン語重子音文字 ss の歴史・地理的解釈 上田博人(東京大学)・Leyre Martín Aizpuru (Universidad de Sevilla) © each contributor 1 語境界線(isogloss)から観察するアラビア語諸方言の様相 長渡陽一(東京外国語大学特別研究員) 本発表の目的は、アラビア語の主な方言の基礎語彙の語境界線(isogloss)を地図化し、使 -

*‡Table 6. Languages

T6 Table[6.[Languages T6 T6 DeweyT6iDecima Tablel[iClassification6.[Languages T6 *‡Table 6. Languages The following notation is never used alone, but may be used with those numbers from the schedules and other tables to which the classifier is instructed to add notation from Table 6, e.g., translations of the Bible (220.5) into Dutch (—3931 in this table): 220.53931; regions (notation —175 from Table 2) where Spanish language (—61 in this table) predominates: Table 2 notation 17561. When adding to a number from the schedules, always insert a decimal point between the third and fourth digits of the complete number Unless there is specific provision for the old or middle form of a modern language, class these forms with the modern language, e.g., Old High German —31, but Old English —29 Unless there is specific provision for a dialect of a language, class the dialect with the language, e.g., American English dialects —21, but Swiss-German dialect —35 Unless there is a specific provision for a pidgin, creole, or mixed language, class it with the source language from which more of its vocabulary comes than from its other source language(s), e.g., Crioulo language —69, but Papiamento —68. If in doubt, prefer the language coming last in Table 6, e.g., Michif —97323 (not —41) The numbers in this table do not necessarily correspond exactly to the numbers used for individual languages in 420–490 and in 810–890. For example, although the base number for English in 420–490 is 42, the number for English in Table 6 is —21, not —2 (Option A: To give local emphasis and a shorter number to a specific language, place it first by use of a letter or other symbol, e.g., Arabic language 6_A [preceding 6_1]. -

The Endangered Languages of Vanuatu

Endangered Austronesian and Australian Aboriginal languages: essays on language documentation, archiving, and revitalization Pacific Linguistics 617 Pacific Linguistics is a publisher specialising in grammars and linguistic descriptions, dictionaries and other materials on languages of the Pacific, Taiwan, the Philippines, Indonesia, East Timor, southeast and south Asia, and Australia. Pacific Linguistics, established in 1963 through an initial grant from the Hunter Douglas Fund, is associated with the School of Culture, History and Language in the College of Asia and the Pacific at The Australian National University. The authors and editors of Pacific Linguistics publications are drawn from a wide range of institutions around the world. Publications are refereed by scholars with relevant expertise, who are usually not members of the editorial board. FOUNDING EDITOR: Stephen A. Wurm EDITORIAL BOARD: I Wayan Arka and Malcolm Ross (Managing Editors), Mark Donohue, Nicholas Evans, David Nash, Andrew Pawley, Paul Sidwell, Jane Simpson, and Darrell Tryon EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD: Karen Adams, Arizona State University Marian Klamer, Universiteit Leiden Alexander Adelaar, University of Melbourne Harold Koch, The Australian National Peter Austin, School of Oriental and African University Studies Frantisek Lichtenberk, University of Byron Bender, University of Hawai‘i Auckland Walter Bisang, Johannes Gutenberg- John Lynch, University of the South Pacific Universität Mainz Patrick McConvell, The Australian National Robert Blust, University of Hawai‘i University David Bradley, La Trobe University William McGregor, Aarhus Universitet Lyle Campbell, University of Hawai’i Ulrike Mosel, Christian-Albrechts- James Collins, Northern Illinois University Universität zu Kiel Bernard Comrie, Max Planck Institute for Claire Moyse-Faurie, Centre National de la Evolutionary Anthropology Recherche Scientifique Matthew Dryer, State University of New York Bernd Nothofer, Johann Wolfgang Goethe- at Buffalo Universität Frankfurt am Main Jerold A. -

Tense, Mood, and Aspect Expressions in Nafsan (South Efate) from a Typological Perspective

Tense, mood, and aspect expressions in Nafsan (South Efate) from a typological perspective e perfect aspect and the realis/irrealis mood Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktorin der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) eingereicht an der Sprach- und literaturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Jointly awarded PhD degree with School of Languages and Linguistics, The University of Melbourne von Ana Krajinović Rodrigues (zitiert als Ana Krajinović) Prof. Dr.-Ing. Dr. Sabine Kunst Prof. Dr. Ulrike Vedder Präsidentin Dekanin der Sprach- und der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin literaturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät Gutachter und Gutachterin: 1. Prof. Dr. Manfred Krifka (Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin) 2. Prof. Dr. Jean-Christophe Verstraete (University of Leuven) 3. Senior Lecturer Dr. Julie Barbour (The University of Waikato) Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 26. Februar 2020 Tense, mood, and aspect expressions in Nafsan (South Efate) from a typological perspective e perfect aspect and the realis/irrealis mood Ana Krajinović Rodrigues (cite as Ana Krajinović) ORCID: 0000-0002-0858-7606 Submitted in total fulfillment of the requirements of the jointly awarded degree of Doctor of Philosophy Institut ür deutsche Sprache und Linguistik, HmboldUniei Belin School of Languages and Linguistics, The Uniei of Melbone April 2020 Abstract In this thesis I study the meaning of tense, mood, and aspect (TMA) expressions in Nafsan (South Efate), an Oceanic language of Vanuatu, from a typological perspective. I focus on the meanings of the perfect aspect and realis/irrealis mood in Nafsan and other Oceanic languages, as case studies for investigating the cross-linguistic features of these TMA categories. Given the diversity of TMA systems in languages of the world, the status of many TMA categories as cross-linguistically valid has been disputed in the linguistic literature.