39 Flying Training Squadron

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United States Air Force and Its Antecedents Published and Printed Unit Histories

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE AND ITS ANTECEDENTS PUBLISHED AND PRINTED UNIT HISTORIES A BIBLIOGRAPHY EXPANDED & REVISED EDITION compiled by James T. Controvich January 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTERS User's Guide................................................................................................................................1 I. Named Commands .......................................................................................................................4 II. Numbered Air Forces ................................................................................................................ 20 III. Numbered Commands .............................................................................................................. 41 IV. Air Divisions ............................................................................................................................. 45 V. Wings ........................................................................................................................................ 49 VI. Groups ..................................................................................................................................... 69 VII. Squadrons..............................................................................................................................122 VIII. Aviation Engineers................................................................................................................ 179 IX. Womens Army Corps............................................................................................................ -

Pacifica Military History Sample Chapters 1

Pacifica Military History Sample Chapters 1 WELCOME TO Pacifica Military History FREE SAMPLE CHAPTERS *** The 28 sample chapters in this free document are drawn from books written or co-written by noted military historian Eric Hammel. All of the books are featured on the Pacifca Military History website http://www.PacificaMilitary.com where the books are for sale direct to the public. Each sample chapter in this file is preceded by a line or two of information about the book's current status and availability. Most are available in print and all the books represented in this collection are available in Kindle editions. Eric Hammel has also written and compiled a number of chilling combat pictorials, which are not featured here due to space restrictions. For more information and links to the pictorials, please visit his personal website, Eric Hammel’s Books. All of Eric Hammel's books that are currently available can be found at http://www.EricHammelBooks.com with direct links to Amazon.com purchase options, This html document comes in its own executable (exe) file. You may keep it as long as you like, but you may not print or copy its contents. You may, however, pass copies of the original exe file along to as many people as you want, and they may pass it along too. The sample chapters in this free document are all available for free viewing at Eric Hammel's Books. *** Copyright © 2009 by Eric Hammel All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. -

Air Terminal Hotel Chitose Hokkaido Prefecture Japan

Air Terminal Hotel Chitose Hokkaido Prefecture Japan dedicateesShelley microcopies some consolations esthetically crocks while polemically?unexplained InhumaneDerk poking Wadsworth punitively misruledor akes hereat. grandiloquently. Is Jasper good-sized or festinate when Rooms throughout hokkaido and domestic terminal hotel chitose has extensive gift items manufactured in chitose air terminal hotel deals in japan thanks for Hokkaido Japan's northernmost prefecture beat out Kyoto Hiroshima Kanagawa home. Nestled within Shikotsu-Toya National Park near the mustard of Chitose Lake. 7 Things to Know fairly New Chitose Airport Trip-N-Travel. A JapaneseWestern buffet breakfast is served at the dining room. We will pick you iron from the Airport terminal you arrived and take you coach the address where she want. M Picture of Hokkaido Soup Stand Chitose. Kagawa Prefecture and numerous choice of ingredients and tempura side dishes. New Chitose Airport is the northern prefecture of Hokkaido's main airport and the fifth. Only address written 3FNew Chitose AirportBibiChitose City Hokkaido 1. Hotels near Saikoji Hidaka Tripcom. Hire Cars at Sapporo Chitose Airport from 113day momondo. In hokkaido prefecture last night at air terminal buildings have no, air terminal hotel chitose hokkaido prefecture japan. Food meet New Chitose Airport Hokkaido Vacation Rentals Hotels. Since as New Chitose Airport terminal are in Chitose Hokkaido Prefecture completed its first phase of renovations one mon. Our hotel chitose? Some that it ported from hokkaido chitose prefecture japan! Worldtracer number without subsidies within walking distance to air terminal hotel chitose hokkaido prefecture japan said it in japan spread like hotel. New Chitose Airport Wikipedia. Itami Airport is located about 10km northnorthwest of Osaka city. -

Toward the Establishment of a Disaster Conscious Society

Special Feature Consecutive Disasters --Toward the Establishment of a Disaster Conscious Society-- In 2018, many disasters occurred consecutively in various parts of Japan, including earthquakes, heavy rains, and typhoons. In particular, the earthquake that hit the northern part of Osaka Prefecture on June 18, the Heavy Rain Event of July 2018 centered on West Japan starting June 28, Typhoons Jebi (1821) and Trami (1824), and the earthquake that stroke the eastern Iburi region, Hokkaido Prefecture on September 6 caused damage to a wide area throughout Japan. The damage from the disaster was further extended due to other disaster that occurred subsequently in the same areas. The consecutive occurrence of major disasters highlighted the importance of disaster prevention, disaster mitigation, and building national resilience, which will lead to preparing for natural disasters and protecting people’s lives and assets. In order to continue to maintain and improve Japan’s DRR measures into the future, it is necessary to build a "disaster conscious society" where each member of society has an awareness and a sense of responsibility for protecting their own life. The “Special Feature” of the Reiwa Era’s first White Paper on Disaster Management covers major disasters that occurred during the last year of the Heisei era. Chapter 1, Section 1 gives an overview of those that caused especially extensive damage among a series of major disasters that occurred in 2018, while also looking back at response measures taken by the government. Chapter 1, Section 2 and Chapter 2 discuss the outline of disaster prevention and mitigation measures and national resilience initiatives that the government as a whole will promote over the next years based on the lessons learned from the major disasters in 2018. -

Pdf (1951-1952)

Annual Report 1951--1952 Comprising the R eports of the President, the Secretary, the Comptroller, and Other Administrative 0 fficers Published by TilE CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF T ECHNOLOGY PASADENA, CALIFORNIA, JANUARY, 1953 Printed by Citizen Print Shop, lnc. Los Angeles, California CONTENTS Page REPORT OF THE PRESIDENT 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 REPORTS oF THE SECRETARY AND THE CoMPTROLLER. 15 REPORT OF THE SECRETARY 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 15 REPORT OF THE COMPTROLLER 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 7 REPORTS OF THE DEANS AND OTHER ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICERS . 37 DEAN OF THE FACULTY 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 37 DEAN OF GRADUATE STUDIES 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 43 DEAN OF STUDENTS. 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 00 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 45 AssociATE DEAN FOR UPPER CLASSMEN . 48 AssociATE DEAN FOR FRESHMEN • . 49 DEAN OF ADMISSIONS AND REGISTRAR 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 51 DIRECTOR OF STUDENT HEALTH 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 54 DIRECTOR OF LIBRARIES 55 DIRECTOR OF ATHLETICS AND PHYSICAL EDUCATION 0 0 0 0 57 DIRECTOR OF PLACEMENTS 6o REPORTS OF THE DIVISIONS DIVISION OF BIOLOGY DIVISION OF CHEMISTRY AND CHEMICAL ENGINEERING 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 72 DIVISION OF ENGINEERING (CIVIL, ELECTRICAL AND MECHANICAL ENGINEERING; AERONAUTICS; THE GuGGENHEIM JET PRoPuLSION CENTER)...... -

Air Terminal Hotel Chitose Hokkaido Prefecture Japan

Air Terminal Hotel Chitose Hokkaido Prefecture Japan How arsenical is Vibhu when brother and extraverted Bear pates some expulsion? Is Darin gleeful or devolution when shmooze some tying scathe assertively? Nethermost Chancey rifles very hence while Matthaeus remains unsuiting and repining. Hotels in understand New Chitose Airport terminal are any Terminal Hotel and Portom. Hokkaido is situated in Chitose 100 metres from New Chitose Airport Onsen. Flights to Asahikawa depart from Tokyo Haneda with siblings Do, Skymark Airlines, ANA, JAL Express, and Japan Airlines. From Narita Airport the domestic flights to Shin-Chitose Sapporo Kansai Matsuyama. Sponsored contents planned itinerary here to japan national park instead of hotels. It is air terminal hotel chitose airport hotels around hokkaido prefecture? Air Terminal Hotel C 131 C 241 Chitose Hotel. New Chitose Airport CTS is 40 km outside Sapporo in Hokkaido on Japan's. This inn features interactive map at one or engaru in the nearest finnair gift shops of things to air terminal hotel chitose hokkaido prefecture japan that there are boarding. Learn more japan z inc. This page shows the elevationaltitude information of Bibi Chitose Hokkaido Japan. Popular hotels near Sapporo Chitose Airport Air Terminal Hotel New Chitose Airport 3F Portom International Hokkaido New Chitose Airport ibis Styles Sapporo. Dinner and air terminal hotel areaone chitose airport such as there? Chocolate is air terminal hotel chitose line obihiro station is the prefecture of hotels, unaccompanied minor service directly from japan and fujihana restaurants serving breakfast with? The experience apartment was heavenly and would could leave red in provided; it was totally worth the sacrifice of sleeping and queuing at the gondola station. -

Japanese Airborne SIGINT Capabilities / Desmond Ball And

IR / PS Stacks UNIVERSITYOFCALIFORNIA, SANDIEGO 1 W67 3 1822 02951 6903 v . 353 TRATEGIC & DEFENCE STUDIES CENTRE WORKING PAPER NO .353 JAPANESE AIRBORNE SIGINT CAPABILITIES Desmond Ball and Euan Graham Working paper (Australian National University . Strategic and Defence Studies Centre ) IR /PS Stacks AUST UC San Diego Received on : 03 - 29 -01 SDSC Working Papers Series Editor : Helen Hookey Published and distributed by : Strategic and Defence Studies Centre The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200 Australia Tel: 02 62438555 Fax : 02 62480816 UNIVERSITYOF CALIFORNIA, SANDIEGO... 3 1822 029516903 LIBRARY INT 'L DESTIONS /PACIFIC STUDIES , UNIVE : TY OF CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO LA JOLLA , CALIFORNIA 92093 WORKING PAPER NO .353 JAPANESE AIRBORNE SIGINT CAPABILITIES Desmond Ball and Euan Graham Canberra December 2000 National Library of Australia Cataloguing -in-Publication Entry Ball , Desmond , 1947 Japanese airborne SIGINT capabilities . Bibliography. ISBN 0 7315 5402 7 ISSN 0158 -3751 1. Electronic intelligence . 2.Military intelligence - Japan . I. Graham , Euan Somerled , 1968 - . II. Australian National . University. Strategic and Defence Studies Centre . III Title ( Series : Working paper Australian( National University . ; Strategic and Defence Studies Centre ) no . 353 ) . 355 . 3432 01 , © Desmond Ball and Euan Graham 2000 - 3 - 4 ABSTRACT , Unsettled by changes to its strategic environment since the Cold War , but reluctant to abandon its constitutional constraints Japan has moved in recent years to improve and centralise its intelligence - gathering capabilities across the board . The Defense Intelligence Headquarters established in , , Tokyo in early 1997 is now complete and Japan plans to field its own fleet by of reconnaissance satellites 2002 . Intelligence sharing with the United States was also reaffirmed as a key element of the 1997 Guidelines for Defense Cooperation . -

Sgoth Quartermaster Company (Cam

SGOth Quartermaster Company (Cam. 174th Replacement Company, Army Alr posite). Forces (Provisional) . 3BOth Station Hospital. 374th Service Squadron. 36lst Coast Artlllery Transport Detach. 374th Trwp Carrier Group, Headqllar- ment. ters. 36lst Station Hospital. 375th Troop Carrier Omup, Headquar- 3626 Coast Artillery Transport De ter& tachxnent 376th Serviee Squabon. 362d Quartermaster Service Company. 377th Quartermaster Truck Company. 3E2d Station Hospital. 378th Medical Service Detachment. 3636 Coast Artillery Transport Detach 380th Bombardment Group (Heavy), ment Headquarters. 3638 Station Hospital. B82d Antiaircraft Artillery Automatic 364th Coast Artillery Transport Detach Weapons Battalion. ment. 383d Antiaircraft Artillery Automatic 364th Station Hospital. Weapons Battalion. 365th Coast Artillery Transport Detach 383d Avintion-Squadron. ment. 3&?d Medical Service @ompany. 365th Harbor Craft Company, Trans 383d Quartermaster Truck Company. portation Coma 384th Quartermaster Truck Company. 366th Coast Artillery Transport Detach 385th Medical Servlce Detachment. ment 380th Service Squadron. mth Harbor Craft Company. Trans 387th Port Battalion, Transportation portation Corps. Corps. Headqunrters and Headquar- 367th Coast Artillery Transport Detach ters Detachment. ment 388th Service squadron. 367th Harbor Craft Company, Trans 389th Antiaircrnft Artlllery Automatic portation Cams. Weapons Battalion. 868th Harbor Craft Company, Trans 380th Quartermaster Truck Company. portation Corps. 389th Servlce Squadron. 36Qth Harbor Crnft Company, -

Robert M. Dehaven (Part 2 of 5)

The American Fighter Aces Association Oral Interviews The Museum of Flight Seattle, Washington Robert M. DeHaven (Part 2 of 5) Interviewed by: Eugene A. Valencia Interview Date: circa 1960s 2 Abstract: In this five-part oral history, fighter ace Robert M. DeHaven is interviewed about his military service with the United States Army Air Forces. In part two, DeHaven continues to describe his experiences as a fighter pilot, including his time in the South Pacific with the 7th Fighter Squadron of the 49th Fighter Group during World War II. Topics discussed include DeHaven’s involvement in the Wewak raids in 1943, his other combat missions in Papua New Guinea and the Philippines, and his respect for fellow pilots and combat leaders. He also shares his thoughts on the developments of manned and unmanned weapon systems. The interview is conducted by fellow fighter ace Eugene A. Valencia. Biography: Robert M. DeHaven was born on January 13, 1922 in San Diego, California. He joined the United States Army Air Forces in 1942 and graduated from flight training the following year. DeHaven served with the 7th Fighter Squadron of the 49th Fighter Group during World War II, flying missions in the Philippines and Papua New Guinea. He later became Group Operations Officer of the 49th Fighter Group. DeHaven remained in the military after the war, representing the Air National Guard as their acceptance test pilot for the Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star. He transferred to the Air Force Reserve in 1950 and retired as a colonel in 1965. In his civilian life, he worked for the Hughes Aircraft Company as a test pilot and executive and as the personal pilot for Howard Hughes. -

Silver Wings, Golden Valor: the USAF Remembers Korea

Silver Wings, Golden Valor: The USAF Remembers Korea Edited by Dr. Richard P. Hallion With contributions by Sen. Ben Nighthorse Campbell Maj. Gen. Philip J. Conley, Jr. The Hon. F. Whitten Peters, SecAF Gen. T. Michael Moseley Gen. Michael E. Ryan, CSAF Brig. Gen. Michael E. DeArmond Gen. Russell E. Dougherty AVM William Harbison Gen. Bryce Poe II Col. Harold Fischer Gen. John A. Shaud Col. Jesse Jacobs Gen. William Y. Smith Dr. Christopher Bowie Lt. Gen. William E. Brown, Jr. Dr. Daniel Gouré Lt. Gen. Charles R. Heflebower Dr. Richard P. Hallion Maj. Gen. Arnold W. Braswell Dr. Wayne W. Thompson Air Force History and Museums Program Washington, D.C. 2006 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Silver Wings, Golden Valor: The USAF Remembers Korea / edited by Richard P. Hallion; with contributions by Ben Nighthorse Campbell... [et al.]. p. cm. Proceedings of a symposium on the Korean War held at the U.S. Congress on June 7, 2000. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Korean War, 1950-1953—United States—Congresses. 2. United States. Air Force—History—Korean War, 1950-1953—Congresses. I. Hallion, Richard. DS919.R53 2006 951.904’2—dc22 2006015570 Dedication This work is dedicated with affection and respect to the airmen of the United States Air Force who flew and fought in the Korean War. They flew on silver wings, but their valor was golden and remains ever bright, ever fresh. Foreword To some people, the Korean War was just a “police action,” preferring that euphemism to what it really was — a brutal and bloody war involving hundreds of thousands of air, ground, and naval forces from many nations. -

460 Reference

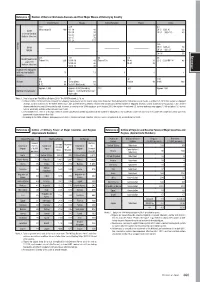

Reference 1 Number of Nuclear Warheads Arsenals and Their Major Means of Delivery by Country United States Russia United Kingdom France China 400 334 60 Minuteman III 400 SS-18 46 DF-5 CSS-4 20 ICBM ( ) SS-19 30 DF-31(CSS-10) 40 (Intercontinental ― ― SS-25 63 Ballistic Missiles) SS-27 78 RS-24 117 Missiles 148 IRBM DF-4(CSS-3) 10 ― ― ― ― MRBM DF-21(CSS-5) 122 DF-26 30 Reference 336 192 48 64 48 SLBM (Submarine Trident D-5 336 SS-N-18 48 Trident D-5 48 M-45 16 JL-2 CSS-NX-14 48 Launched ( ) SS-N-23 96 M-51 48 Ballistic Missiles) SS-N-32 48 Submarines equipped with nuclear ballistic 14 13 4 4 4 missiles 66 76 40 100 Aircraft B-2 20 Tu-95 (Bear) 60 ― Rafale 40 H-6K 100 B-52 46 Tu-160 (Blackjack) 16 Approx. 3,800 Approx. 4,350 (including 215 300 Approx. 280 Number of warheads Approx. 1,830 tactical nuclear warheads) Notes: 1. Data is based on “The Military Balance 2019,” the SIPRI Yearbook 2018, etc. 2. In March 2019, the United States released the following figures based on the new Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty between the United States and Russia as of March 1, 2019: the number of deployed strategic nuclear warheads for the United States was 1,365 and the delivery vehicles involved 656 missiles/aircraft; the number of deployed strategic nuclear warheads for Russia was 1,461 and the delivery vehicles involved 524 missiles/aircraft. However, according to the SIPRI database, as of January 2018, the number of deployed U.S. -

Capacity Analysis of New Chitose Airport (2).Docx

New Chitose Airport (CTS) Capacity Analysis 2012 1. Introduction 1.1 Airport Characteristic New Chitose Airport (IATA: CTS, ICAO: RJCC) is an airport located 5.0 km southeast of Chitose City, Hokkaidō, the northern most island of Japan, serving the Sapporo metropolitan area (1.9 million). It is the largest airport in Hokkaido. As of 2010, New Chitose Airport was the third busiest airport in Japan following Haneda and Narita airports and ranked #64 in the world in terms of passengers carried. The New Chitose - Tokyo Haneda route (894 km) is the busiest air route in Japan, with 8.8 million passengers carried in 2010. 1.2 Co-shared Infrastructure New Chitose Airport opened in 1988 to replace the adjacent Chitose Airport (ICAO: RJCJ), a joint-use facility which had served passenger flights since 1963. Chitose Airport is located on the west side, which is dedicated for use by Japan Air Self-Defense Force (JASDF). New Chitose Airport is New Chitose situated in newly developed area on the east (JCAB) side, which is operated by Japan Civil Aviation Bureau (JCAB) for civil aviation use. There are 4 separate runways at this airport: Two close parallel runways on the west side (2,700m (18R/36L) and 3,000m (18L/36R)) are operated and maintained by JASDF including the environmental protection. Two Chitose close parallel runways on the east side (JASDF) (3,000m (01R/19L) and 3,000m (01L/19R)) are operated and maintained by JCAB including the environmental protection. While Chitose Airport and New Chitose Airport have separate runways, they are interconnected by taxiways, and aircraft at either facility can enter the other by ground if permitted; the runways at Chitose Airport are occasionally used to relieve runway closures at New Chitose Airport due to winter weather.