Silver Wings, Golden Valor: the USAF Remembers Korea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

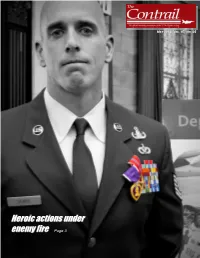

Heroic Actions Under Enemy Fire Page 3

MAY 2013, VOL. 47, NO. 05 HeroicHeroic actionsactions underunder enemyenemy firefire Page 3 PILOTPILOT FORFOR AA DAY!DAY! AY OL O M 2013, V . 47, N . 05 FEATURES: Pg. 3: Heroic Actions Pg. 5: NDI life under lights Pg. 6: Pilot for a Day! Pg. 7: Spirit of A.C. part 3 And more... COVER: Sears, an explosive ordnance disposal technician with the 177th Fighter Wing, defused two improvised explo- sive devices and made five trips across open terrain un- der heavy enemy fire to aid a wounded coalition soldier and to engage insurgent forces. Photo by Master Sgt. Mark Olsen SOCIAL MEDIA Find us on the web! www.177thFW.ang.af.mil Facebook.com/177FW Twitter.com/177FW Youtube.com/177thfighterwing This funded newspaper is an authorized monthly 177TH FW EDITORIAL STAFF publication for members of the U.S. Military Services. Col. Kerry M. Gentry, Commander Contents of the Contrail are not necessarily the official 1st Lt. Amanda Batiz, Public Affairs Officer Master Sgt. Andrew Moseley, Public Affairs/Visual Information Manager view of, or endorsed by, the 177th FW, the U.S. Gov- Master Sgt. Shawn Mildren:, Photographer ernment, the Department of Defense or the Depart- Tech. Sgt. Andrew Merlock Jr., Photographer Tech. Sgt. Matt Hecht: Editor, Layout, Photographer, Writer ment of the Air Force. The editorial content is edited, prepared, and provided by the Public Affairs Office of 177FW/PA the 177th Fighter Wing. All photographs are Air Force 400 Langley Road, Egg Harbor Township, NJ 08234-9500 (609) 761-6259; (609) 677-6741 (FAX) photographs unless otherwise indicated. -

United States Air Force and Its Antecedents Published and Printed Unit Histories

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE AND ITS ANTECEDENTS PUBLISHED AND PRINTED UNIT HISTORIES A BIBLIOGRAPHY EXPANDED & REVISED EDITION compiled by James T. Controvich January 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTERS User's Guide................................................................................................................................1 I. Named Commands .......................................................................................................................4 II. Numbered Air Forces ................................................................................................................ 20 III. Numbered Commands .............................................................................................................. 41 IV. Air Divisions ............................................................................................................................. 45 V. Wings ........................................................................................................................................ 49 VI. Groups ..................................................................................................................................... 69 VII. Squadrons..............................................................................................................................122 VIII. Aviation Engineers................................................................................................................ 179 IX. Womens Army Corps............................................................................................................ -

Major General Timothy M. Ray U N I T E D S T a T E S a I R F O R

Page 1 of 3 U N I T E D S T A T E S A I R F O R C E MAJOR GENERAL TIMOTHY M. RAY Maj. Gen. Timothy Ray is the Director of Global Power Programs in the Office of the Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Acquisition, Headquarters U.S. Air Force, Washington, D.C. He is responsible for the directing, planning and programming of 159 Air Force, joint service and international programs with a $10 billion annual budget. General Ray received his commission from the U.S. Air Force Academy in 1985. He completed undergraduate pilot training and has held operational flying assignments in the T-38 and B- 52, serving as an instructor, evaluator pilot and squadron commander. He has also flown the B-1 and commanded the 7th Bomb Wing at Dyess Air Force Base, Texas. General Ray had various staff assignments at the major command, Headquarters U.S. Air Force and combatant command levels, as well as served as Commanding General, NATO Air Training Command – Afghanistan, NATO Training Mission – Afghanistan/Combined Security Transition Command – Afghanistan; and Commander, 438th Air Expeditionary Wing, Kabul, Afghanistan. Prior to his current assignment, he was Director, Operational Planning, Policy and Strategy, Deputy Chief of Staff, Operations, Plans and Requirements, Headquarters U.S. Air Force, Washington, D.C. EDUCATION 1985 Bachelor of Science degree in human factors engineering, U.S. Air Force Academy, Colorado Springs, Colo. 1994 Distinguished graduate, Squadron Officer School, Maxwell AFB, Ala. 1998 Master of Science degree in aviation sciences and management, Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, Daytona Beach, Fla. -

Air Force Sexual Assault Court-Martial Summaries 2010 March 2015

Air Force Sexual Assault Court-Martial Summaries 2010 March 2015 – The Air Force is committed to preventing, deterring, and prosecuting sexual assault in its ranks. This report contains a synopsis of sexual assault cases taken to trial by court-martial. The information contained herein is a matter of public record. This is the final report of this nature the Air Force will produce. All results of general and special courts-martial for trials occurring after 1 April 2015 will be available on the Air Force’s Court-Martial Docket Website (www.afjag.af.mil/docket/index.asp). SIGNIFICANT AIR FORCE SEXUAL ASSAULT CASE SUMMARIES 2010 – March 2015 Note: This report lists cases involving a conviction for a sexual assault offense committed against an adult and also includes cases where a sexual assault offense against an adult was charged and the member was either acquitted of a sexual assault offense or the sexual assault offense was dismissed, but the member was convicted of another offense involving a victim. The Air Force publishes these cases for deterrence purposes. Sex offender registration requirements are governed by Department of Defense policy in compliance with federal and state sex offender registration requirements. Not all convictions included in this report require sex offender registration. Beginning with July 2014 cases, this report also indicates when a victim was represented by a Special Victims’ Counsel. Under the Uniform Code of Military Justice, sexual assaults against those 16 years of age and older are charged as crimes against adults. The appropriate disposition of sexual assault allegations and investigations may not always include referral to trial by court-martial. -

HOMETOWN HEROES HOMETOWN HEROES Heroic Stories from Brave Men and Women by Greg Mclntyre

HOMETOWN HEROES HOMETOWN HEROES Heroic Stories From Brave Men and Women by Greg Mclntyre www.mcelderlaw.com Copyright © 2018 by Greg Mclntyre All Rights Reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical or electronic, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright holder. Published by Shelby House Publishing Web: www.mcelderlaw.com FRONT COVER IMAGE BIO he image on the front cover of this book is my Tgrandfather, J.C. Horne, in all his military splendor. Even today, reading the interview I did with him gives me chills. I loved that man with all my heart, he was my buddy. It’s hard for me to accept that the gentle man I knew and loved as my grandfather experienced the atrocities mentioned in his story. I can only imagine what four days R&R in Paris was like when you’d been fighting on the front lines during World War Two in Europe. You can read the interview with him in this book. Without veterans like my grandfather, we may not have a great country to call home. We owe Veterans our freedom. The world would be a much different place than it is today without their sacrifice. It is our duty to take care of them. PREFACE ’m Elder Law Attorney Greg McIntyre of McIntyre Elder Law. My passion is helping seniors protect their assets and legacies. II am also a veteran of the US Navy. I served on the USS Constellation and the USS Nimitz. -

2021-03 Pearcey Newby and the Vulcan V2.Pdf

Journal of Aeronautical History Paper 2021/03 Pearcey, Newby, and the Vulcan S C Liddle Vulcan to the Sky Trust ABSTRACT In 1955 flight testing of the prototype Avro Vulcan showed that the aircraft’s buffet boundary was unacceptably close to the design cruise condition. The Vulcan’s status as one of the two definitive carrier aircraft for Britain’s independent nuclear deterrent meant that a strong connection existed between the manufacturer and appropriate governmental research institutions, in this case the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) and the National Physical Laboratory (NPL). A solution was rapidly implemented using an extended and drooped wing leading edge, designed and high-speed wind-tunnel tested by K W Newby of RAE, subsequently being fitted to the scaled test version of the Vulcan, the Avro 707A. Newby’s aerodynamic solution exploited a leading edge supersonic-expansion, isentropic compression* effect that was being investigated at the time by researchers at NPL, including H H Pearcey. The latter would come to be associated with this ‘peaky’ pressure distribution and would later credit the Vulcan implementation as a key validation of the concept, which would soon after be used to improve the cruise efficiency of early British jet transports such as the Trident, VC10, and BAC 1-11. In turn, these concepts were exploited further in the Hawker-Siddeley design for the A300B, ultimately the basis of Britain’s status as the centre of excellence for wing design in Airbus. Abbreviations BS Bristol Siddeley L Lift D Drag M Mach number CL Lift Coefficient NPL National Physical Laboratory Cp Pressure coefficient RAE Royal Aircraft Establishment Cp.te Pressure coefficient at trailing edge RAF Royal Air Force c Chord Re Reynolds number G Load factor t Thickness HS Hawker Siddeley WT Wind tunnel HP Handley Page α Angle of Attack When the airflow past an aerofoil accelerates its pressure and temperature drop, and vice versa. -

General Disclaimer One Or More of the Following Statements May Affect

General Disclaimer One or more of the Following Statements may affect this Document This document has been reproduced from the best copy furnished by the organizational source. It is being released in the interest of making available as much information as possible. This document may contain data, which exceeds the sheet parameters. It was furnished in this condition by the organizational source and is the best copy available. This document may contain tone-on-tone or color graphs, charts and/or pictures, which have been reproduced in black and white. This document is paginated as submitted by the original source. Portions of this document are not fully legible due to the historical nature of some of the material. However, it is the best reproduction available from the original submission. Produced by the NASA Center for Aerospace Information (CASI) PB94-123205 Human Performance Models for Computer-Aided Engineering National Research Council, Washington, DC Prepared for: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Washington, DC 1989 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE NMNational Technical Information Service REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMS No. 0704-0188 II I'lllIIIIIII IIf 2. Report Date , 3. Report Type And Dates Covered: IIIII II INI^II III 1989 PB94-123205 4. Title And Subtitle: Human performance models 5. Funding Numbers: for computer-aided engineering Grant no. NAG-2-407 6. Author(s): Editors: Jerome I. Elkind, Stuart K. Card;Julian Hochberg; Beverly Messick Huey 7. Performing Organization Names And Addresses: S. Performing Organization National Research Council Commission on Behavior Report Number: al and Social Sciences and Education Committee on Human Factors Panel on Pilot Performance Models in a Computer- Aided Design Facility 9. -

Cradle of Airpower Education

Cradle of Airpower Education Maxwell Air Force Base Centennial April 1918 – April 2018 A Short History of The Air University, Maxwell AFB, and the 42nd Air Base Wing Air University Directorate of History March 2019 1 2 Cradle of Airpower Education A Short History of The Air University, Maxwell AFB, and 42nd Air Base Wing THE INTELLECTUAL AND LEADERSHIP- DEVELOPMENT CENTER OF THE US AIR FORCE Air University Directorate of History Table of Contents Origins and Early Development 3 The Air Corps Tactical School Period 3 Maxwell Field during World War II 4 Early Years of Air University 6 Air University during the Vietnam War 7 Air University after the Vietnam War 7 Air University in the Post-Cold War Era 8 Chronology of Key Events 11 Air University Commanders and Presidents 16 Maxwell Post/Base Commanders 17 Lineage and Honors: Air University 20 Lineage and Honors: 42nd Bombardment Wing 21 “Be the intellectual and leadership-development center of the Air Force Develop leaders, enrich minds, advance airpower, build relationships, and inspire service.” 3 Origins and Early Development The history of Maxwell Air Force Base began with Orville and Wilbur Wright, who, following their 1903 historic flight, decided in early 1910 to open a flying school to teach people how to fly and to promote the sale of their airplane. After looking at locations in Florida, Wilbur came to Montgomery, Alabama in February 1910 and decided to open the nation’s first civilian flying school on an old cotton plantation near Montgomery that subsequently become Maxwell Air Force Base (AFB). -

Historical Dictionary of Air Intelligence

Historical Dictionaries of Intelligence and Counterintelligence Jon Woronoff, Series Editor 1. British Intelligence, by Nigel West, 2005. 2. United States Intelligence, by Michael A. Turner, 2006. 3. Israeli Intelligence, by Ephraim Kahana, 2006. 4. International Intelligence, by Nigel West, 2006. 5. Russian and Soviet Intelligence, by Robert W. Pringle, 2006. 6. Cold War Counterintelligence, by Nigel West, 2007. 7. World War II Intelligence, by Nigel West, 2008. 8. Sexspionage, by Nigel West, 2009. 9. Air Intelligence, by Glenmore S. Trenear-Harvey, 2009. Historical Dictionary of Air Intelligence Glenmore S. Trenear-Harvey Historical Dictionaries of Intelligence and Counterintelligence, No. 9 The Scarecrow Press, Inc. Lanham, Maryland • Toronto • Plymouth, UK 2009 SCARECROW PRESS, INC. Published in the United States of America by Scarecrow Press, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.scarecrowpress.com Estover Road Plymouth PL6 7PY United Kingdom Copyright © 2009 by Glenmore S. Trenear-Harvey All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Trenear-Harvey, Glenmore S., 1940– Historical dictionary of air intelligence / Glenmore S. Trenear-Harvey. p. cm. — (Historical dictionaries of intelligence and counterintelligence ; no. 9) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN-13: 978-0-8108-5982-1 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8108-5982-3 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8108-6294-4 (eBook) ISBN-10: 0-8108-6294-8 (eBook) 1. -

Leadership Lab I: Become an Airman

Civil Air Patrol Performing Missions For America Leadership Lab I: Become An Airman SER-GA-045 Sandy Springs U.S. AIR FORCE AUXILIARY Cadet Squadron – 2016 Rev. Basic Training Cycle Indoctrination Module Pass these tests: Pass the online open book LL1 test! Pass the LL1 LL 1 Module drill test! Promote To Memorize and Cadet recite the Cadet Airman! Graduation Oath! and Award Pass the Cadet of the Snoopy AE1 Module Physical Fitness Test! Patch! Move to A Flt! Pass Online Open Book ES1 - Activities Module GES Test! Pass ES module quizzes Performing Missions For America 2 Learning Objectives CAP Memory Items Be a Wingman The Warrior Spirit Discipline and Attitude TAKE NOTES – Core Values yellow highlighted Cadet Oath items are test items Need for Leadership Training Customs and Courtesies Drill and Ceremonies The Uniform Performing Missions For America 3 Be A Wingman Fighter Wingman Concept Mutual support is a key part of aerial combat and has been since the beginning of combat aviation. “The wingman is absolutely indispensable. I When two pilots look after the wingman. The wingman looks enter a fight with a after me. It’s another set of eyes protecting you. common goal, That’s the defensive part. Offensively, it gives you a lot more firepower. We work together. We sharing the same fight together. The wingman knows what his approach, the responsibilities are, and knows what mine are. enemy must work Wars are not won by individuals. They’re won by exponentially harder teams.” — Lt. Col. Francis S. “Gabby” Gabreski, USAF to defeat them. (Fighter Ace, 34.5 kills, WW2 and Korea) Performing Missions For America 4 Protect Your Wingman! Watch out for each other: Physically Eating well, drinking water, sleeping well, showering daily, getting injuries treated. -

Airpower in Three Wars

AIRPOWER IN THREE WARS GENERAL WILLIAM W. MOMYER USAF, RET. Reprint Edition EDITORS: MANAGING EDITOR - LT COL A. J. C. LAVALLE, MS TEXTUAL EDITOR - MAJOR JAMES C. GASTON, PHD ILLUSTRATED BY: LT COL A. J. C. LAVALLE Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama April 2003 Air University Library Cataloging Data Momyer, William W. Airpower in three wars / William W. Momyer ; managing editor, A. J. C. Lavalle ; textual editor, James C. Gaston ; illustrated by A. J. C. Lavalle–– Reprinted. p. ; cm. With a new preface. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-58566-116-3 1. Airpower. 2. World War, 1939–1945––Aerial operations. 3. Korean War. 1950–1953––Aerial operations. 4. Vietnamese Conflict, 1961–1975––Aerial oper- ations. 5. Momyer, William W. 6. Aeronautics, Military––United States. I. Title. II. Lavalle, A. J. C. (Arthur J. C.), 1940– III. Gaston, James C. 358.4/009/04––dc21 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public release. Air University Press 131 West Shumacher Avenue Maxwell AFB AL 36112-6615 http://aupress.maxwell.af.mil ii TO . all those brave airmen who fought their battles in the skies for command of the air in World War II, Korea, and Vietnam. iii THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK PREFACE 2003 When I received the request to update my 1978 foreword to this book, I thought it might be useful to give my perspective of some aspects on the employment of airpower in the Persian Gulf War, the Air War over Serbia (Operation Allied Force), and the war in Afghanistan (Operation Enduring Freedom). -

Air Force Training: Further Analysis and Planning Needed to Improve Effectiveness, GAO-16-635SU (Washington, D.C.: Aug

United States Government Accountability Office Report to Congressional Committees September 2016 AIR FORCE TRAINING Further Analysis and Planning Needed to Improve Effectiveness GAO-16-864 September 2016 AIR FORCE TRAINING Further Analysis and Planning Needed to Improve Effectiveness Highlights of GAO-16-864, a report to congressional committees Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found For more than a decade, the Air Force The Air Force establishes combat aircrew training requirements for the full range focused its training on supporting of core missions based on an annual process, but these requirements may not operations in the Middle East. The Air reflect current and emerging training needs, because the Air Force has not Force has established goals for its comprehensively reassessed the assumptions underlying them. Specifically, combat aircrews to conduct training for assumptions about the total annual live-fly sortie requirements by aircraft, the the full range of core missions. Both criteria for designating aircrews as experienced or inexperienced, and the mix the Senate and House Reports between live and simulator training have remained the same since 2012. For accompanying bills for the FY 2016 example, Air Combat Command has set the same minimum number of live-fly National Defense Authorization Act sortie requirements across aircraft platforms, but has not conducted the analysis included a provision for GAO to review needed to determine if requirements should differ based on the number of core the Air Force’s training plans. missions for each platform. Reassessing the assumptions underlying annual This report discusses the extent to training requirements would better position the Air Force to meet its stated goals which the Air Force has (1) determined for its forces to achieve a range of missions for current and emerging threats.