Closing the Loopholes in Vietnam's New Copyright Laws Than Nguyen Luu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploiting Prior Knowledge During Automatic Key and Chord Estimation from Musical Audio

Exploitatie van voorkennis bij het automatisch afleiden van toonaarden en akkoorden uit muzikale audio Exploiting Prior Knowledge during Automatic Key and Chord Estimation from Musical Audio Johan Pauwels Promotoren: prof. dr. ir. J.-P. Martens, prof. dr. M. Leman Proefschrift ingediend tot het behalen van de graad van Doctor in de Ingenieurswetenschappen Vakgroep Elektronica en Informatiesystemen Voorzitter: prof. dr. ir. R. Van de Walle Faculteit Ingenieurswetenschappen en Architectuur Academiejaar 2015 - 2016 ISBN 978-90-8578-883-6 NUR 962, 965 Wettelijk depot: D/2016/10.500/15 Abstract Chords and keys are two ways of describing music. They are exemplary of a general class of symbolic notations that musicians use to exchange in- formation about a music piece. This information can range from simple tempo indications such as “allegro” to precise instructions for a performer of the music. Concretely, both keys and chords are timed labels that de- scribe the harmony during certain time intervals, where harmony refers to the way music notes sound together. Chords describe the local harmony, whereas keys offer a more global overview and consequently cover a se- quence of multiple chords. Common to all music notations is that certain characteristics of the mu- sic are described while others are ignored. The adopted level of detail de- pends on the purpose of the intended information exchange. A simple de- scription such as “menuet”, for example, only serves to roughly describe the character of a music piece. Sheet music on the other hand contains precise information about the pitch, discretised information pertaining to timing and limited information about the timbre. -

Raja Mohan 21M.775 Prof. Defrantz from Bronx's Hip-Hop To

Raja Mohan 21M.775 Prof. DeFrantz From Bronx’s Hip-Hop to Bristol’s Trip-Hop As Tricia Rose describes, the birth of hip-hop occurred in Bronx, a marginalized city, characterized by poverty and congestion, serving as a backdrop for an art form that flourished into an international phenomenon. The city inhabited a black culture suffering from post-war economic effects and was cordoned off from other regions of New York City due to modifications in the highway system, making the people victims of “urban renewal.” (30) Given the opportunity to form new identities in the realm of hip-hop and share their personal accounts and ideologies, similar to traditions in African oral history, these people conceived a movement whose worldwide appeal impacted major events such as the Million Man March. Hip-hop’s enormous influence on the world is undeniable. In the isolated city of Bristol located in England arose a style of music dubbed trip-hop. The origins of trip-hop clearly trace to hip-hop, probably explaining why artists categorized in this genre vehemently oppose to calling their music trip-hop. They argue their music is hip-hop, or perhaps a fresh and original offshoot of hip-hop. Mushroom, a member of the trip-hop band Massive Attack, said, "We called it lover's hip hop. Forget all that trip hop bullshit. There's no difference between what Puffy or Mary J Blige or Common Sense is doing now and what we were doing…” (Bristol Underground Website) Trip-hop can abstractly be defined as music employing hip-hop, soul, dub grooves, jazz samples, and break beat rhythms. -

SNICK - Round 10

SNICK - Round 10 1. A stuffed animal from this man's childhood inspired a supposedly super-cool character that he voiced in the short-lived Fox Kids cartoon C-Bear and Jamal. A banker named Biderman utterly baffles a criminal played by this man by telling him things like "the horse is in the barn" and "the chicken is in the pot" in the film Blank Check; that character is named Juice. This man voiced a goanna lizard who sings "If I'm Gonna Eat Somebody (It Might As Well Be You)" in (*) FernGully two years before he played Emilio, a Miami cop who assists the title character of Ace Ventura: Pet Detective. For 10 points, name this raspy-voiced man who also rapped the hits "Wild Thing" and "Funky Cold Medina." ANSWER: Tone Lōc (loke) (or Anthony (Terrell) Smith) <Vopava, Trends/Miscellany> 2. One song on this album was re-recorded with vocals by William S. Burroughs for an X-Files soundtrack. Initial printings of this album unusually had a translucent yellow disc tray. A song on this album quickly repeats the phrase "call me when you try to wake her" and is based on (*) "The Lion Sleeps Tonight." This album's original name, Star, referenced an ornament that appears on its cover, though it was ultimately named for the slogan of Weaver D's, a restaurant in Athens, Georgia. A single from this album describes "when the day is long, and the night is yours alone," while another poses numerous questions to Andy Kaufmann. "Man on the Moon" and "Everybody Hurts" appear on, for 10 points, what 1992 album by R.E.M.? ANSWER: Automatic for the People <Nelson, Music> 3. -

The Arts and Entertainment Supplement to the Daily Nexus, For

4 The Arts and Entertainment Supplement to the Daily Nexus, for December 1st through December 7th, 1994 1 Textures. Rhythms. nute due to pressure from Beats. These three things the police department. are important attributes to Are you used to that kind any song. But how are of thing? Discuss the cur these characteristics coal rent state of dance culture esced? In the world of in England. dance music, hardly any Paul Hartnoll: Oh, one does this as well as Or there’s loads of rubbish bital. Their recent show at going on in England, isn’t the Shrine Auditorium there.... Unless you do ev proved that not only are erything well above board, they the premiere house/ you’re really setting your techno group, but further self up for trouble, and if proved that die emergence you get away with it, it’s of underground dance lucky, with underground music is a force steadily be parties where it’s not coming impossible to ig strictly organized.... Even nore as we approach the if you hire the place off of next century, coupled with someone, you might have the imminent death of a license to have that many rock music. Artsweek'% people in it. You’ve got to Monty Luke cornered Phil be lucky to get away with and Paul Hartnoll of Orbi it. tal in Los Angeles to dis Especially now with the cuss music, politics and criminal justice bill gone spiders. through, if you get caught Artsweek: 1 under doing something like that, stand the venue for Satur day[ night's'. -

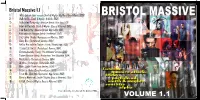

Bristol Massive

Bristol Massive 1.1 1) Intro (edited short version, Smith & Mighty:: Big World Small World, 2000) 2) Walk on By (Smith & Mighty:: Dj Kicks, 2001) 3) Unfinished Sympathy (Massive Attack:: Blue Line, 1991) 4) Down in Rwanda (Smith & Mighty:: Bass is Maternal, 1995) 5) Five Man Army (Massive Attack: Blue Lines, 1991) 6) Karmacoma (Massive Attack: Protection , 1996) 7) Overcome (Tricky:: Maxinquaye, w/Martina, 1995) 8) Glory Box (Portishead:: Dummy, 1994) 9) Hell is Around the Corner (Tricky:: Maxinquaye, 1995) 10) It Could Be Sweet (Portishead:: Dummy, 1994) 11) Christiansands (Tricky:: Pre-millennial Tension, 1996) 12) Three (Massive Attack:: Protection/ feat. Nicollete, 1994) 13) Mysterions (Portishead:: Dummy, 1994) 14) All Mine (Portishead:: Portishead, 1998) 15) Rain (Alpha:: Come From Heaven, 1998) 16) Delaney (Alpha:: ComeFromHeaven, 1998) 17) Trust Me (Roni Size/Reprazent:: New Forms, 1998) 18) Bass is Maternal (Smith & Mighty, Bass is Maternal, 1995) 19) U-Dub (Smithy & Mighty, Bass is Maternal, 1995) tracks selected by Jerry Saturn @ The Masthead, 2004 Bristol Massive 1.2 1) Closer (Smith & Mighty:: Bass is Maternal, 1995) 2) Jungle Man Corner (Smith & Mighty:: Bass is Maternal, 1995) 3) Spying Glass (Massive Attack:: Protection, w/ Horace Andy, 1996) 4) No Justice (Smith & Mighty:: Big World, Small World, 2000) 5) Be Thankful For What You Got (Massive Attack:: Blue Lines, 1991) 6) Sour Times (Portishead:: Dummy, 1994) 7) With (Alpha:: ComeFromHeaven, 1998) 8) Undenied (Portishead:: Portishead, 1998) 9) Move You Run (Smith & Mighty:: -

Portisheads Dummy Ebook, Epub

PORTISHEADS DUMMY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Rj Wheaton | 144 pages | 07 Dec 2011 | Continuum Publishing Corporation | 9781441194497 | English | New York, United States Portisheads Dummy PDF Book Learn how to enable JavaScript on your browser. Massive Attack came out of eight years of work in sound systems, and had a strong Caribbean identity. It was really awkward. Alain Badiou is undoubtedly the most exciting and influential voice in contemporary French philosophy and one of the most important theorists at work today. He could make his organ just go from barely audible to absolutely take your head off. You played the really wobbly bass stuff, which is the majority of it. And in Gibbons it offered a bleak, twisted and completely novel vision of what a blues singer could be. Utley: I think that's really super cool. The track opens with nearly a full minute of dark, spacious chords ringing out from a Fender Rhodes electric piano through a Fender Twin , with the bass cranked with the onboard tremolo cranked to deliver the pulsing vibe that gives the song its underlying rhythm. You've worked out the weird kind of chords that she had. Continue on UK site. They said that the snare drum sounds like a tin can. In fact, one of the first sounds you hear on the record—that ethereal, Theremin-like lead on "Mysterons"—was actually conjured out of the SH Initially created as an affordable and somewhat simplified alternative to Roland's more advanced synthesizers, the SH has attracted a loyal following since its release in So how did Portishead craft the signature sound of Dummy? People must have told you they use this music for all kinds of situations. -

Volunteers Begin Work on Shelter

If : Eing-tum ¡ ¡ ¡ 1 W a s h in g t o n a n d L e e U n iv e r s it y ’s W e e k l y N e w s p a p e r * V o l u m e 101, N o . 18 L e x in g t o n , V ir g in ia 24450 M o n d a y , M a r c h 15,1999 Volunteers begin work on shelter Students team up with Lex community to build shelter for battered women the second in conjunction with Habi a lot for that, but this is really the criti By Polly Doig tat. Both organizations acknowledge cal bit.” N ew s E ditor a difference between this and previ When completed, the shelter will The normal quiet of the woods ous projects. be 4,400 square feet over three floors, surrounding the Student Activities “Usually we just build houses for two of which will be fully finished, and Pavilion was shattered this weekend low-income families, and this has then a partially-finished basement. The . by the sound of power tools. added a whole other aspect to it — house will greatly improve Project The Timber Framers Guild rolled protecting people who are victims of Horizon’s abilities to shelter victims of into town to begin work on a shelter domestic violence,” Josh Beckham, domestic violence, which currently for battered women in conjunction president of the W&L chapter of averages two or three days. with Habitat for Humanity and Project Habitat, said. -

Turcotte Christian 2016 Memoire.Pdf

Université de Montréal GABRIEL FAURÉ ET PORTISHEAD : L’ART DE L’ÉQUIVOQUE Cadre d’analyse théorique de l’équivoque mélodique et harmonique comme principe de transversalité par Christian Turcotte Université de Montréal Faculté de Musique Mémoire présenté à la Faculté de Musique en vue de l’obtention du grade de maîtrise en musicologie 12 janvier 2016 © Christian Turcotte, 2016 Résumé Ce travail de recherche propose une description du style mélodique et harmonique du groupe britannique Portishead et s’appuie sur l’analyse du répertoire complet, soit 33 chansons réparties sur trois albums (11 chansons par albums). Étant donné que le corpus étudié est restreint, il est possible de procéder à une analyse statistique qui permet de dégager une grammaire mélodico-harmonique. L’hypothèse de ce travail de recherche repose sur l’idée que l’évolution du langage musical de Portishead s’articule autour de procédés mélodiques et harmoniques favorisant un élargissement d’un cadre tonal équivoque. Pour ce faire, Portishead a recours à plusieurs procédés mélodiques et harmoniques qui entretiennent l’équivoque tonale. Or, ces procédés sont similaires, sans toutefois être identiques, aux six procédés répertoriés par Sylvain Caron (Caron 2002) au sujet de la grammaire de Gabriel Fauré. Par la mise en œuvre de plusieurs outils d’analyses, nous procédons à une étude comparée et contextualisée de certains mécanismes mélodique et harmonique qui font émerger l’équivoque, tant chez Fauré que chez Portishead. Ces outils d’analyse, comme l’analyse des vecteurs de ruptures mélodico-harmoniques, l’analyse paradigmatique ou l’analyse néo-riemannienne, ont été bonifiés afin de rendre compte de certaines particularités liées au corpus étudié. -

Steal the Feel Sampling Feature 12.11 Layout;6.Indd

TECHNIQUE STEAL THE FEEL How To Build Tracks Around Sampled Tunes Sampling a record may be child’s play, but using phrases, for example) as long as the tempo-shift range is modest; perhaps such samples effectively in your own compositions a five percent stretch either way. When you make larger tempo adjustments to requires plenty of skill and finesse. complex mixed audio, though, noisy and harmonically rich components of MIKE SENIOR algorithm is built into pretty much every the signal will start exhibiting ‘wavery’ DAW now, and they usually produce processing artifacts, and transients can excellent results with simple non-percussive sound smeared or flammed. One way to usic that’s based around samples (solo vocal or instrumental circumvent this for samples containing samples of commercial records M is big business these days, and getting started with this kind of production seems easy, requiring little more than a computer, some DAW software, and a few CDs. In reality, though, fitting a sample from one record into a whole new production presents plenty of practical challenges, both while making the music and when creating a final mix. In this article, I’ll explore how to tackle these challenges so that they don’t stand in the way of your creativity. Matching Tempo & Pitch A primary concern with any rhythmic This screenshot shows a drum loop that has been ‘sliced’ in Reaper, to sync it to a slower sample is matching its tempo to that of project, a tempo-matching technique that often sounds more transparent than time-stretching your track. -

Acoustic Sounds Catalog Update

Analogue Productions and Quality Record Pressings are proud to announce the newest incarnation of titles to be pressed at 45 RPM on 200-gram vinyl. Ladies and gentlemen: The Doors! Additionally, these will also be available on Multichannel Hybrid SACD. The Doors Strange Days Waiting For The Sun Soft Parade Morrison Hotel L.A. Woman AAPP 74007-45 AAPP 74014-45 AAPP 74024-45 AAPP 75005-45 AAPP 75007-45 AAPP 75011-45 $50.00 $50.00 $50.00 $50.00 $50.00 $50.00 (two 45-RPM LPs) (two 45-RPM LPs) (two 45-RPM LPs) (two 45-RPM LPs) (two 45-RPM LPs) (two 45-RPM LPs) Multichannel Hybrid Multichannel Hybrid Multichannel Hybrid No SACD available No SACD available Multichannel Hybrid SACD SACD SACD for this title for this title SACD CAPP 74007 SA CAPP 74014 SA CAPP 74024 SA CAPP 75011 SA $30.00 $30.00 $30.00 $30.00 Cut from the original analog masters by Doug Sax, with the exception of The Doors, which was made from the best tape copy. Sax and Doors producer/engineer Bruce Botnick went through a meticulous setup to guarantee a positively stunning reissue series. This is an all-tubes process. These masters were recorded on tube equipment and the tape machine used for transfer for these releases is a tube machine, as is the cutting system. Tubes, baby! A truly authentic reissue project. Also available: Mr. Mojo Risin’: The Doors By The Doors The Story Of L.A. Woman The Doors by The Doors – a Featuring exclusive interviews with Ray huge, gorgeous volume in which Manzarek, John Densmore, Robby Krieger the band tells its own story – is colleagues and collaborators, exclusive per- now available. -

Music in Bits and Bits of Music

Ragnhild Brøvig-Hanssen Music in Bits and Bits of Music Signatures of Digital Mediation in Popular Music Recordings Music in Bits and Bits of Music Signatures of Digital Mediation in Popular Music Recordings Ragnhild Brøvig-Hanssen A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Department of Musicology Faculty of Humanities University of Oslo 2013 Contents Acknowledgments vii 1. Introduction 1 Methodology 5 A Digital Revolution? 12 Opaque and Transparent Mediation 14 Studying Technological Parameters 22 Outline of the Thesis 29 2. The Spatiotemporal Disjuncture of Music 33 The Mechanical Era of Schizophonia 35 The Magnetic Era of Schizophonia 38 The Digital Era of Schizophonia 42 The Development of Different Recording Paradigms 49 Conclusion 57 3. Making Sense of Digital Spatiality: Kate Bush’s Spatial Collage 61 Conceptualizing and Fabricating Spatiality in Music 63 A House of Surrealistic Spaces 69 A House of Terrifying Spaces 78 Conclusion 83 4. The Rebirth of Silence in the Company of Noise: 85 Portishead’s Lo-Fi/Hi-Fi Music Digital Silence and the Holy Grail of “High Fidelity” 86 Past Medium Signatures Revisited 91 Portishead Going Retro 95 Conclusion 104 5. Cut-Ups and Glitches: DJ Food’s Freeze and Flow 105 Digital Cut-Ups and Signal Dropouts in “Break” 106 The Double Meaning of Aestheticized Malfunctions 114 Music within the Music 119 Conclusion 122 6. Mash-Ups and Digital Recycling: 125 Justin Bieber featuring Slipknot Mash-Ups as a Digital Signature of Music Recycling 127 “Psychosocial Baby” 133 Consumption as Mode of Production 141 Conclusion 148 7. -

Making Old Machines Speak: Images of Technology in Recent Music* Joseph Auner, SUNY Stony Brook

ECHO: a music-centered journal www.humnet.ucla.edu/echo Volume 2 Issue 2 (Fall 2000) Making Old Machines Speak: Images of Technology in Recent Music* Joseph Auner, SUNY Stony Brook 1. Narratives of progress and innovation have dominated the story of music and technology throughout the twentieth century. The pursuit of ever-greater expressivity, control, responsiveness, clarity, and power, can be charted in instrument design, the whole story of hi-fidelity audio equipment, and the digital revolutions that are transforming musical production, distribution, and reception.1 Referring to the visual arts, Leo Marx has identified a rhetoric of the "technological sublime," in which images of technology are invested with "the capacity to evoke emotions—awe, wonder, mystery, fear—formerly reserved for images of boundless nature or for representing a response to divinity" (qtd. in Jones, 631). In music as well, technology has been both used and represented as the embodiment of the modern, of authority, and of the future. One need only think of the celebrations of the railroad, the factory, speed and motion in works by the Italian and Russian Futurists, the role of the machine in the Weimar era Zeitoper, and Boulez’s high-tech utopias of modern music at IRCAM. 2. The corollary to notions of technological progress is a rejection of what is out of date, a sense of repellence of the outmoded. Writing in 1930 in Reaktion und Fortschritt Theodor Adorno described surrealistic montage techniques as depending on the "‘scandal’ produced when the dead suddenly spring up among the living" (qtd. in Paddison 90-91).