Making Old Machines Speak: Images of Technology in Recent Music* Joseph Auner, SUNY Stony Brook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diapositive 1

From Body-space to Technospace: The Virtualization of Urban Experience in Music Videos Christophe Den Tandt Université Libre de Bruxelles Postcolonialism and Postmodernity Research Group January 2010 Music videos: expanding the realm of performance . Music videos transport performers “out of a musical context—into the everyday (the street, the home) [or] into the fantastic (the dream, the wilderness)” (Simon Frith, Performing Rites: On the Value of Popular Music, 1996, p. 225) The Cardigans: “For What It’s Worth” Placebo: “The Bitter End” The New Radicals. “You Get What You Give” Music videos: expanding the realm of performance Into the streets: Dancing in the streets (carnivalesque appropriation) Roaming the streets (alienated subjects in the asphalt Jungle) Dancing in the virtual streets (exploring virtualized urban space) Dancing in the streets Lavigne, Avril. “Sk8ter Boy.” Music video. Dir. Francis Lawrence. 2002. Dancing in the streets Appropriation of urban space Generational solidarity Subcultural channels Carnivalesque empowerment Roaming the streets Avril Lavigne: “I’m With You” Faithless: “Insomnia.” Dir. Lindy Heymann. (1996). Placebo: “The Bitter End” John Huston’s The Asphalt Jungle (1950) Dancing in the virtual streets The Red Hot Chili Peppers. Californication. Music video. Dirs. Jonathan Dayton and Valerie Faris. 2000. Dancing in the virtual streets Postmodern pastiche Computer graphics / virtual reality Cf. Cyberpunk SF: William Gibson’s Neuromancer (1984); Virtual Light (1993); Andy and Larry Wachowski. The Matrix. 1998 Jean Baudrillard. Simulation and Simulacra ? Body-space vs. technospace How can videos map the issues involved in the virtualization of urban experience? Music videos = performing artists transposed out of customary performance space to new locales Performance, agency (body-space) defined with regard to the technologies of the informational megalopolis (techno-space). -

Exploiting Prior Knowledge During Automatic Key and Chord Estimation from Musical Audio

Exploitatie van voorkennis bij het automatisch afleiden van toonaarden en akkoorden uit muzikale audio Exploiting Prior Knowledge during Automatic Key and Chord Estimation from Musical Audio Johan Pauwels Promotoren: prof. dr. ir. J.-P. Martens, prof. dr. M. Leman Proefschrift ingediend tot het behalen van de graad van Doctor in de Ingenieurswetenschappen Vakgroep Elektronica en Informatiesystemen Voorzitter: prof. dr. ir. R. Van de Walle Faculteit Ingenieurswetenschappen en Architectuur Academiejaar 2015 - 2016 ISBN 978-90-8578-883-6 NUR 962, 965 Wettelijk depot: D/2016/10.500/15 Abstract Chords and keys are two ways of describing music. They are exemplary of a general class of symbolic notations that musicians use to exchange in- formation about a music piece. This information can range from simple tempo indications such as “allegro” to precise instructions for a performer of the music. Concretely, both keys and chords are timed labels that de- scribe the harmony during certain time intervals, where harmony refers to the way music notes sound together. Chords describe the local harmony, whereas keys offer a more global overview and consequently cover a se- quence of multiple chords. Common to all music notations is that certain characteristics of the mu- sic are described while others are ignored. The adopted level of detail de- pends on the purpose of the intended information exchange. A simple de- scription such as “menuet”, for example, only serves to roughly describe the character of a music piece. Sheet music on the other hand contains precise information about the pitch, discretised information pertaining to timing and limited information about the timbre. -

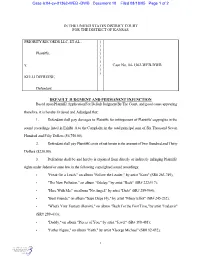

RIAA/Defreese/Proposed Default Judgment and Permanent Injunction

Case 6:04-cv-01362-WEB -DWB Document 10 Filed 08/18/05 Page 1 of 2 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF KANSAS PRIORITY RECORDS LLC, ET AL., ) ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) ) v. ) Case No. 04-1362-WEB-DWB ) ) KELLI DEFREESE, Defendant. DEFAULT JUDGMENT AND PERMANENT INJUNCTION Based upon Plaintiffs' Application For Default Judgment By The Court, and good cause appearing therefore, it is hereby Ordered and Adjudged that: 1. Defendant shall pay damages to Plaintiffs for infringement of Plaintiffs' copyrights in the sound recordings listed in Exhibit A to the Complaint, in the total principal sum of Six Thousand Seven Hundred and Fifty Dollars ($6,750.00). 2. Defendant shall pay Plaintiffs' costs of suit herein in the amount of Two Hundred and Thirty Dollars ($230.00). 3. Defendant shall be and hereby is enjoined from directly or indirectly infringing Plaintiffs' rights under federal or state law in the following copyrighted sound recordings: C "Freak On a Leash," on album "Follow the Leader," by artist "Korn" (SR# 263-749); C "The New Pollution," on album "Odelay," by artist "Beck" (SR# 222-917); C "Here With Me," on album "No Angel," by artist "Dido" (SR# 289-904); C "Best Friends," on album "Supa Dupa Fly," by artist "Missy Elliot" (SR# 245-232); C "What's Your Fantasy (Remix)," on album "Back For the First Time," by artist "Ludacris" (SR# 289-433); C "Daddy," on album "Pieces of You," by artist "Jewel" (SR# 198-481); C "Father Figure," on album "Faith," by artist "George Michael" (SR# 92-432); 1 Case 6:04-cv-01362-WEB -DWB Document -

Raja Mohan 21M.775 Prof. Defrantz from Bronx's Hip-Hop To

Raja Mohan 21M.775 Prof. DeFrantz From Bronx’s Hip-Hop to Bristol’s Trip-Hop As Tricia Rose describes, the birth of hip-hop occurred in Bronx, a marginalized city, characterized by poverty and congestion, serving as a backdrop for an art form that flourished into an international phenomenon. The city inhabited a black culture suffering from post-war economic effects and was cordoned off from other regions of New York City due to modifications in the highway system, making the people victims of “urban renewal.” (30) Given the opportunity to form new identities in the realm of hip-hop and share their personal accounts and ideologies, similar to traditions in African oral history, these people conceived a movement whose worldwide appeal impacted major events such as the Million Man March. Hip-hop’s enormous influence on the world is undeniable. In the isolated city of Bristol located in England arose a style of music dubbed trip-hop. The origins of trip-hop clearly trace to hip-hop, probably explaining why artists categorized in this genre vehemently oppose to calling their music trip-hop. They argue their music is hip-hop, or perhaps a fresh and original offshoot of hip-hop. Mushroom, a member of the trip-hop band Massive Attack, said, "We called it lover's hip hop. Forget all that trip hop bullshit. There's no difference between what Puffy or Mary J Blige or Common Sense is doing now and what we were doing…” (Bristol Underground Website) Trip-hop can abstractly be defined as music employing hip-hop, soul, dub grooves, jazz samples, and break beat rhythms. -

Toxicological Profile for Acetone Draft for Public Comment

ACETONE 1 Toxicological Profile for Acetone Draft for Public Comment July 2021 ***DRAFT FOR PUBLIC COMMENT*** ACETONE ii DISCLAIMER Use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, the Public Health Service, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. This information is distributed solely for the purpose of pre dissemination public comment under applicable information quality guidelines. It has not been formally disseminated by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. It does not represent and should not be construed to represent any agency determination or policy. ***DRAFT FOR PUBLIC COMMENT*** ACETONE iii FOREWORD This toxicological profile is prepared in accordance with guidelines developed by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The original guidelines were published in the Federal Register on April 17, 1987. Each profile will be revised and republished as necessary. The ATSDR toxicological profile succinctly characterizes the toxicologic and adverse health effects information for these toxic substances described therein. Each peer-reviewed profile identifies and reviews the key literature that describes a substance's toxicologic properties. Other pertinent literature is also presented, but is described in less detail than the key studies. The profile is not intended to be an exhaustive document; however, more comprehensive sources of specialty information are referenced. The focus of the profiles is on health and toxicologic information; therefore, each toxicological profile begins with a relevance to public health discussion which would allow a public health professional to make a real-time determination of whether the presence of a particular substance in the environment poses a potential threat to human health. -

SA Expands Internship-For-Credit Program, Invites Students To

The UWM Post SA expands internship-for-credit program, Post photo by Sampson Parsons invites students to Women's Leadership creasing awareness and educating [email protected] or pickup an eappli By Bryan G. Pfeifer people about women's issues on cation for the SA Intern Program a campus, state, and national at Union E351. Applications are level." The UWM Student Association due by 5 p.m. Friday, Feb. 5. The conference will include (SA), representing the university's workshop or session topics on "In- 23,000-plus students on campus "Inviting Voices, Living Out Loud" volvementin the Political Arena," and at the UW system level, has ex UWM SAsenators and students "Childcare Issues," "Women and panded its internship program will take part in the 3rd annual the Media," "Self-defense Work beginning this semester. Women's Leadership Conference shops," "Race and Gender," SA President Jeff Robb said the tided "Inviting Voices, Living Out "Women and War," and many oth SA Intern Program offers student Loud," at UW-Platteville Feb. 12- ers. interns between two andsix credit 13. The keynote speaker is Elena hours. Previously, students could SA Senator Talia Schanck said Featherston, editor of the book only receive volunteer credit about 12-15 students from UWM Skin Deep: Women Writing on through UWM's School of Educa will be attending the conference. Color, Culture & Identity and di tion and internship experience A representative from the rector of the award-winning docu did not focus on a student's ma Women's Resource Center, mentary Alice Walker: Visions of jor. -

Sample Some of This

Sample Some Of This, Sample Some Of That (169) ✔ KEELY SMITH / I Wish You Love [Capitol (LP)] JEHST / Bluebells [Low Life (EP)] RAMSEY LEWIS TRIO / Concierto De Aranjuez [Cadet (LP)] THE COUP / The Liberation Of Lonzo Williams [Wild Pitch (12")] EYEDEA & ABILITIES / E&A Day [Epitaph (LP)] CEE-KNOWLEDGE f/ Sun Ra's Arkestra / Space Is The Place [Counterflow (12")] JOHN DANKWORTH & HIS ORCHESTRA / Bernie's Tune ("Off Duty", O.S.T.) [Fontana (LP)] COMMON & MARK THE 45 KING / Car Horn (Madlib remix) [Madlib (LP)] GANG STARR / All For Da Ca$h [Cooltempo/Noo Trybe (LP)] JOHN DANKWORTH & HIS ORCHESTRA / Theme From "Return From The Ashes", O.S.T. [RCA (LP)] 7 NOTAS 7 COLORES / Este Es Un Trabajo Para Mis… [La Madre (LP)] QUASIMOTO / Astronaut [Antidote (12")] DJ ROB SWIFT / The Age Of Television [Om (LP)] JOHN DANKWORTH & HIS ORCHESTRA / Look Stranger (From BBC-TV Series) [RCA (LP)] THE LARGE PROFESSOR & PETE ROCK / The Rap World [Big Beat/Atlantic (LP)] JOHN DANKWORTH & HIS ORCHESTRA / Two-Piece Flower [Montana (LP)] GANG STARR f/ Inspectah Deck / Above The Clouds [Noo Trybe (LP)] Sample Some Of This, Sample Some Of That (168) ✔ GABOR SZABO / Ziggidy Zag [Salvation (LP)] MAKEBA MOONCYCLE / Judgement Day [B.U.K.A. (12")] GABOR SZABO / The Look Of Love [Buddah (LP)] DIAMOND D & SADAT X f/ C-Low, Severe & K-Terrible / Feel It [H.O.L.A. (12")] GABOR SZABO / Love Theme From "Spartacus" [Blue Thumb (LP)] BLACK STAR f/ Weldon Irvine / Astronomy (8th Light) [Rawkus (LP)] GABOR SZABO / Sombrero Man [Blue Thumb (LP)] ACEYALONE / The Hunt [Project Blowed (LP)] GABOR SZABO / Gloomy Day [Mercury (LP)] HEADNODIC f/ The Procussions / The Drive [Tres (12")] GABOR SZABO / The Biz [Orpheum Musicwerks (LP)] GHETTO PHILHARMONIC / Something 2 Funk About [Tuff City (LP)] GABOR SZABO / Macho [Salvation (LP)] B.A. -

Song Title Artist Genre

Song Title Artist Genre - General The A Team Ed Sheeran Pop A-Punk Vampire Weekend Rock A-Team TV Theme Songs Oldies A-YO Lady Gaga Pop A.D.I./Horror of it All Anthrax Hard Rock & Metal A** Back Home (feat. Neon Hitch) (Clean)Gym Class Heroes Rock Abba Megamix Abba Pop ABC Jackson 5 Oldies ABC (Extended Club Mix) Jackson 5 Pop Abigail King Diamond Hard Rock & Metal Abilene Bobby Bare Slow Country Abilene George Hamilton Iv Oldies About A Girl The Academy Is... Punk Rock About A Girl Nirvana Classic Rock About the Romance Inner Circle Reggae About Us Brooke Hogan & Paul Wall Hip Hop/Rap About You Zoe Girl Christian Above All Michael W. Smith Christian Above the Clouds Amber Techno Above the Clouds Lifescapes Classical Abracadabra Steve Miller Band Classic Rock Abracadabra Sugar Ray Rock Abraham, Martin, And John Dion Oldies Abrazame Luis Miguel Latin Abriendo Puertas Gloria Estefan Latin Absolutely ( Story Of A Girl ) Nine Days Rock AC-DC Hokey Pokey Jim Bruer Clip Academy Flight Song The Transplants Rock Acapulco Nights G.B. Leighton Rock Accident's Will Happen Elvis Costello Classic Rock Accidentally In Love Counting Crows Rock Accidents Will Happen Elvis Costello Classic Rock Accordian Man Waltz Frankie Yankovic Polka Accordian Polka Lawrence Welk Polka According To You Orianthi Rock Ace of spades Motorhead Classic Rock Aces High Iron Maiden Classic Rock Achy Breaky Heart Billy Ray Cyrus Country Acid Bill Hicks Clip Acid trip Rob Zombie Hard Rock & Metal Across The Nation Union Underground Hard Rock & Metal Across The Universe Beatles -

Permitting an End to Pollution

Permitting how to scrutinize and an End to strengthen water pollution permits in your state Pollution A handbook by: Robert Moore | Prairie Rivers Network Merritt Frey | Clean Water Network Gayle Killam | River Network June 2002 Acknowledgments This handbook is based on an earlier, Illinois-specific version developed by Prairie Rivers Network. Brett Schmidt, a volunteer for Prairie Rivers, deserves a great deal of thanks for its contents. In many ways he is the person who spurred its creation by assembling information to orient new volunteers at Prairie Rivers Network to assist in reviewing NPDES permits in Illinois. In addition, we would like to recognize Prairie Rivers Network staff members Emily Bergner, Jeannie Brantigan and Dixie Jackson for their contributions. The authors would also like to thank the Project Staff people who have helped make this handbook possible and have given us a great deal of Art Direction and Design assistance in improving it and reviewing Tanyia Johnson preliminary drafts. We would like to thank the Greer Graphics Inc. many members of the Clean Water Network who provided us with feedback on early drafts Production Coordinator of the handbook, lending their experience and Gabriela Stocks expertise to us. In addition, we’d like to thank Mary Frey and River Network staff for editing Front Cover Photo the handbook. John Marshall River Network Prairie Rivers Network Clean Water Network 520 SW Sixth Avenue, Suite 1130 809 South Fifth Street 1200 New York Ave., N.W., #400 Portland, OR 97204-1511 Champaign, IL 61820 Washington D.C. 20005 tel: (503) 241-3506 tel: (217) 344-2371 tel: (202) 289-2395 fax: (503) 241-9256 fax: (217) 344-2381 fax: (202) 289-1060 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.rivernetwork.org www.prairierivers.org www.cwn.org ISBN #1930407-08-04 © 2002 by Prairie Rivers Network Clean Water Network River Network Printed on 100% recycled, 75% postconsumer, 100% processed chlorine free paper. -

AC/DC BONFIRE 01 Jailbreak 02 It's a Long Way to the Top 03 She's Got

AC/DC AEROSMITH BONFIRE PANDORA’S BOX DISC II 01 Toys in the Attic 01 Jailbreak 02 Round and Round 02 It’s a Long Way to the Top 03 Krawhitham 03 She’s Got the Jack 04 You See Me Crying 04 Live Wire 05 Sweet Emotion 05 T.N.T. 06 No More No More 07 Walk This Way 06 Let There Be Rock 08 I Wanna Know Why 07 Problem Child 09 Big 10” Record 08 Rocker 10 Rats in the Cellar 09 Whole Lotta Rosie 11 Last Child 10 What’s Next to the Moon? 12 All Your Love 13 Soul Saver 11 Highway to Hell 14 Nobody’s Fault 12 Girls Got Rhythm 15 Lick and a Promise 13 Walk All Over You 16 Adam’s Apple 14 Shot Down in Flames 17 Draw the Line 15 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap 18 Critical Mass 16 Ride On AEROSMITH PANDORA’S BOX DISC III AC/DC 01 Kings and Queens BACK IN BLACK 02 Milk Cow Blues 01 Hells Bells 03 I Live in Connecticut 02 Shoot to Thrill 04 Three Mile Smile 05 Let It Slide 03 What Do You Do For Money Honey? 06 Cheesecake 04 Given the Dog a Bone 07 Bone to Bone (Coney Island White Fish) 05 Let Me Put My Love Into You 08 No Surprize 06 Back in Black 09 Come Together 07 You Shook Me All Night Long 10 Downtown Charlie 11 Sharpshooter 08 Have a Drink On Me 12 Shithouse Shuffle 09 Shake a Leg 13 South Station Blues 10 Rock and Roll Ain’t Noise Pollution 14 Riff and Roll 15 Jailbait AEROSMITH 16 Major Barbara 17 Chip Away the Stone PANDORA’S BOX DISC I 18 Helter Skelter 01 When I Needed You 19 Back in the Saddle 02 Make It 03 Movin’ Out AEROSMITH 04 One Way Street PANDORA’S BOX BONUS CD 05 On the Road Again 01 Woman of the World 06 Mama Kin 02 Lord of the Thighs 07 Same Old Song and Dance 03 Sick As a Dog 08 Train ‘Kept a Rollin’ 04 Big Ten Inch 09 Seasons of Wither 05 Kings and Queens 10 Write Me a Letter 06 Remember (Walking in the Sand) 11 Dream On 07 Lightning Strikes 12 Pandora’s Box 08 Let the Music Do the Talking 13 Rattlesnake Shake 09 My Face Your Face 14 Walkin’ the Dog 10 Sheila 15 Lord of the Thighs 11 St. -

The Snow Miser Song 6Ix Toys - Tomorrow's Children (Feat

(Sandy) Alex G - Brite Boy 1910 Fruitgum Company - Indian Giver 2 Live Jews - Shake Your Tuchas 45 Grave - The Snow Miser Song 6ix Toys - Tomorrow's Children (feat. MC Kwasi) 99 Posse;Alborosie;Mama Marjas - Curre curre guagliò still running A Brief View of the Hudson - Wisconsin Window Smasher A Certain Ratio - Lucinda A Place To Bury Strangers - Straight A Tribe Called Quest - After Hours Édith Piaf - Paris Ab-Soul;Danny Brown;Jhene Aiko - Terrorist Threats (feat. Danny Brown & Jhene Aiko) Abbey Lincoln - Lonely House - Remastered Abbey Lincoln - Mr. Tambourine Man Abner Jay - Woke Up This Morning ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE - Are We Experimental? Adolescents - Democracy Adrian Sherwood - No Dog Jazz Afro Latin Vintage Orchestra - Ayodegi Afrob;Telly Tellz;Asmarina Abraha - 808 Walza Afroman - I Wish You Would Roll A New Blunt Afternoons in Stereo - Kalakuta Republik Afu-Ra - Whirlwind Thru Cities Against Me! - Transgender Dysphoria Blues Aim;Qnc - The Force Al Jarreau - Boogie Down Alabama Shakes - Joe - Live From Austin City Limits Albert King - Laundromat Blues Alberta Cross - Old Man Chicago Alex Chilton - Boplexity Alex Chilton;Ben Vaughn;Alan Vega - Fat City Alexia;Aquilani A. - Uh La La La AlgoRythmik - Everybody Gets Funky Alice Russell - Humankind All Good Funk Alliance - In the Rain Allen Toussaint - Yes We Can Can Alvin Cash;The Registers - Doin' the Ali Shuffle Amadou & Mariam - Mon amour, ma chérie Ananda Shankar - Jumpin' Jack Flash Andrew Gold - Thank You For Being A Friend Andrew McMahon in the Wilderness - Brooklyn, You're -

SNICK - Round 10

SNICK - Round 10 1. A stuffed animal from this man's childhood inspired a supposedly super-cool character that he voiced in the short-lived Fox Kids cartoon C-Bear and Jamal. A banker named Biderman utterly baffles a criminal played by this man by telling him things like "the horse is in the barn" and "the chicken is in the pot" in the film Blank Check; that character is named Juice. This man voiced a goanna lizard who sings "If I'm Gonna Eat Somebody (It Might As Well Be You)" in (*) FernGully two years before he played Emilio, a Miami cop who assists the title character of Ace Ventura: Pet Detective. For 10 points, name this raspy-voiced man who also rapped the hits "Wild Thing" and "Funky Cold Medina." ANSWER: Tone Lōc (loke) (or Anthony (Terrell) Smith) <Vopava, Trends/Miscellany> 2. One song on this album was re-recorded with vocals by William S. Burroughs for an X-Files soundtrack. Initial printings of this album unusually had a translucent yellow disc tray. A song on this album quickly repeats the phrase "call me when you try to wake her" and is based on (*) "The Lion Sleeps Tonight." This album's original name, Star, referenced an ornament that appears on its cover, though it was ultimately named for the slogan of Weaver D's, a restaurant in Athens, Georgia. A single from this album describes "when the day is long, and the night is yours alone," while another poses numerous questions to Andy Kaufmann. "Man on the Moon" and "Everybody Hurts" appear on, for 10 points, what 1992 album by R.E.M.? ANSWER: Automatic for the People <Nelson, Music> 3.