Transportation Dividend Technical Appendices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conceptual Plan

About the Cover Photo The photo on the cover of this report was taken on December 17, 2010, around 8:00 AM. The view is from the Savin Hill Avenue overpass and looks almost directly south. This overpass is shown in Figure 3-3 of the report, and the field of view includes land shown in Figure 3-2. At the right is the recently completed headhouse of the Savin Hill Red Line station. Stopped at the station platform is an inbound Red Line train that started at Ashmont and will travel to Alewife. The station is fully ADA-compliant, and the plan presented in this report requires no modification to this station. Next to the Red Line train is an inbound train from one of the three Old Colony commuter rail branches. There is only one track at this location, as is the case throughout most of the Old Colony system. This train has a mixed consist of single-level and bi-level coaches, and is being pushed by a diesel locomotive, which is mostly hidden from view by the bi-level coaches. Between the two trains is an underpass beneath the Ashmont branch of the Red Line. This had been a freight spur serving an industrial area on the west side of the Ashmont branch tracks. Sections A-2.3 and A-2.4 of this report present an approach to staging railroad reconstruction that utilizes the abandoned freight spur and underpass. The two tracks to the left of the Old Colony tracks serve the Braintree Red Line branch. -

Transportation Impact Study

The Harvest Club 255 Elm Street Somerville, Massachusetts Transportation Impact Study Prepared For: The Harvest Club Prepared by: Design Consultants, Inc. January 2021 255 ELM STREET TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................. 5 1.2 Study Area .................................................................................................................. 5 1.3 Safety Analysis ............................................................................................................ 5 1.4 Trip Generation ........................................................................................................... 5 1.5 Intersection Capacity Analysis .................................................................................... 6 1.6 Conclusion .................................................................................................................. 6 2. EXISTING CONDITIONS INVENTORY ................................................................................. 11 2.1 Study Area ................................................................................................................ 11 2.1.1 Study Roadways ................................................................................................. 11 2.1.2 Study Intersections ............................................................................................. -

CHAPTER 2 Progress Since the Last PMT

CHAPTER 2 Progress Since the Last PMT The 2003 PMT outlined the actions needed to bring the MBTA transit system into a state of good repair (SGR). It evaluated and prioritized a number of specific enhancement and expansion projects proposed to improve the system and better serve the regional mobility needs of Commonwealth residents. In the inter- vening years, the MBTA has funded and implemented many of the 2003 PMT priorities. The transit improvements highlighted in this chapter have been accomplished in spite of the unsus- tainable condition of the Authority’s present financial structure. A 2009 report issued by the MBTA Advisory Board1 effectively summarized the Authority’s financial dilemma: For the past several years the MBTA has only balanced its budgets by restructuring debt liquidat- ing cash reserves, selling land, and other one-time actions. Today, with credit markets frozen, cash reserves depleted and the real estate market at a stand still, the MBTA has used up these options. This recession has laid bare the fact that the MBTA is mired in a structural, on-going deficit that threatens its viability. In 2000 the MBTA was re-born with the passage of the Forward Funding legislation.This legislation dedicated 20% of all sales taxes collected state-wide to the MBTA. It also transferred over $3.3 billion in Commonwealth debt from the State’s books to the T’s books. In essence, the MBTA was born broke. Throughout the 1990’s the Massachusetts sales tax grew at an average of 6.5% per year. This decade the sales tax has barely averaged 1% annual growth. -

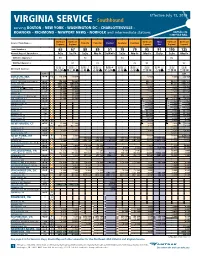

Amtrak Timetables-Virginia Service

Effective July 13, 2019 VIRGINIA SERVICE - Southbound serving BOSTON - NEW YORK - WASHINGTON DC - CHARLOTTESVILLE - ROANOKE - RICHMOND - NEWPORT NEWS - NORFOLK and intermediate stations Amtrak.com 1-800-USA-RAIL Northeast Northeast Northeast Silver Northeast Northeast Service/Train Name4 Palmetto Palmetto Cardinal Carolinian Carolinian Regional Regional Regional Star Regional Regional Train Number4 65 67 89 89 51 79 79 95 91 195 125 Normal Days of Operation4 FrSa Su-Th SaSu Mo-Fr SuWeFr SaSu Mo-Fr Mo-Fr Daily SaSu Mo-Fr Will Also Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 Will Not Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 9/2 R B y R B y R B y R B y R B s R B y R B y R B R s y R B R B On Board Service4 Q l å O Q l å O l å O l å O r l å O l å O l å O y Q å l å O y Q å y Q å Symbol 6 R95 BOSTON, MA ∑w- Dp l9 30P l9 30P 6 10A 6 30A 86 10A –South Station Boston, MA–Back Bay Station ∑v- R9 36P R9 36P R6 15A R6 35A 8R6 15A Route 128, MA ∑w- lR9 50P lR9 50P R6 25A R6 46A 8R6 25A Providence, RI ∑w- l10 22P l10 22P 6 50A 7 11A 86 50A Kingston, RI (b(™, i(¶) ∑w- 10 48P 10 48P 7 11A 7 32A 87 11A Westerly, RI >w- 11 05P 11 05P 7 25A 7 47A 87 25A Mystic, CT > 11 17P 11 17P New London, CT (Casino b) ∑v- 11 31P 11 31P 7 45A 8 08A 87 45A Old Saybrook, CT ∑w- 11 53P 11 53P 8 04A 8 27A 88 04A Springfield, MA ∑v- 7 05A 7 25A 7 05A Windsor Locks, CT > 7 24A 7 44A 7 24A Windsor, CT > 7 29A 7 49A 7 29A Train 495 Train 495 Hartford, CT ∑v- 7 39A Train 405 7 59A 7 39A Berlin, CT >v D7 49A 8 10A D7 49A Meriden, CT >v D7 58A 8 19A D7 58A Wallingford, CT > D8 06A 8 27A D8 06A State Street, CT > q 8 19A 8 40A 8 19A New Haven, CT ∑v- Ar q q 8 27A 8 47A 8 27A NEW HAVEN, CT ∑v- Ar 12 30A 12 30A 4 8 41A 4 9 03A 4 88 41A Dp l12 50A l12 50A 8 43A 9 05A 88 43A Bridgeport, CT >w- 9 29A Stamford, CT ∑w- 1 36A 1 36A 9 30A 9 59A 89 30A New Rochelle, NY >w- q 10 21A NEW YORK, NY ∑w- Ar 2 30A 2 30A 10 22A 10 51A 810 22A –Penn Station Dp l3 00A l3 25A l6 02A l5 51A l6 45A l7 17A l7 25A 10 35A l11 02A 11 05A 11 35A Newark, NJ ∑w- 3 20A 3 45A lR6 19A lR6 08A lR7 05A lR7 39A lR7 44A 10 53A lR11 22A 11 23A 11 52A Newark Liberty Intl. -

Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority

y NOTE WONOERLAND 7 THERE HOLDERS Of PREPAID PASSES. ON DECEMBER , 1977 WERE 22,404 2903 THIS AMOUNTS TO AN ESTIMATED (44 ,608 ) PASSENGERS PER DAY, NOT INCLUDED IN TOTALS BELOW REVERE BEACH I OAK 8R0VC 1266 1316 MALOEN CENTER BEACHMONT 2549 1569 SUFFOLK DOWNS 1142 ORIENT< NTS 3450 WELLINGTON 5122 WOOO ISLANC PARK 1071 AIRPORT SULLIVAN SQUARE 1397 6668 I MAVERICK LCOMMUNITY college 5062 LECHMERE| 2049 5645 L.NORTH STATION 22,205 6690 HARVARD HAYMARKET 6925 BOWDOIN , AQUARIUM 5288 1896 I 123 KENDALL GOV CTR 1 8882 CENTRAL™ CHARLES^ STATE 12503 9170 4828 park 2 2 766 i WASHINGTON 24629 BOYLSTON SOUTH STATION UNDER 4 559 (ESSEX 8869 ARLINGTON 5034 10339 "COPLEY BOSTON COLLEGE KENMORE 12102 6102 12933 WATER TOWN BEACON ST. 9225' BROADWAY HIGHLAND AUDITORIUM [PRUDENTIAL BRANCH I5I3C 1868 (DOVER 4169 6063 2976 SYMPHONY NORTHEASTERN 1211 HUNTINGTON AVE. 13000 'NORTHAMPTON 3830 duole . 'STREET (ANDREW 6267 3809 MASSACHUSETTS BAY TRANSPORTATION AUTHORITY ricumt inoicati COLUMBIA APFKOIIUATC 4986 ONE WAY TRAFFIC 40KITT10 AT RAPID TRANSIT LINES STATIONS (EGLESTON SAVIN HILL 15 98 AMD AT 3610 SUBWAY ENTRANCES DECEMBER 7,1977 [GREEN 1657 FIELDS CORNER 4032 SHAWMUT 1448 FOREST HILLS ASHMONT NORTH OUINCY I I I 99 8948 3930 WOLLASTON 2761 7935 QUINCY CENTER M b 6433 It ANNUAL REPORT Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/annualreportmass1978mass BOARD OF DIRECTORS 1978 ROBERT R. KILEY Chairman and Chief Executive Officer RICHARD D. BUCK GUIDO R. PERERA, JR. "V CLAIRE R. BARRETT THEODORE C. LANDSMARK NEW MEMBERS OF THE BOARD — 1979 ROBERT L. FOSTER PAUL E. MEANS Chairman and Chief Executive Officer March 20, 1979 - January 29. -

Directions to Boston - Local Parking

Directions to Boston - Local Parking GENERAL INFORMATION Logan Express (Recommended) The Back Bay Logan Express runs from all airport terminals directly to St. James Street in Copley Square in Back Bay diagonally across the street from the hotel. Departures occur at :00, :20, and :40 from 5am to 9pm daily. Fares are $7.50 per passenger – payment is by Visa, MasterCard, American Express and Diners Club (NO CASH). All buses are wheelchair accessible. Subway The closest subway stations are Copley Station (on the Green Line) and Back Bay Station (on the Orange Line). Both stations are within 1 block of the hotel. The MBTA runs daily from 6:00 AM to 1:00 AM. The schedule varies based on line, day of week, and reliability of the service. The cost is $2.75 per ride. Cab Transportation Green transportation is available through Lifestyle Transportation International (LTI) and Boston Cabs. Both transportation companies offer hybrid and Flex-Fuel vehicles in their fleet. Taxi fares from the airport to the hotel range from $40-50. PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION From Airport via Subway From airport terminal take a MassPort shuttle bus to the Airport subway station. Take the inbound Blue Line train to Government Center. Then, transfer to any outbound Green Line train to go to Copley station. Make a right onto Dartmouth Street - the hotel is 300 feet down the block on the same side of the street. The fare is $2.75. OR From airport terminal take any Silver Line bus to South Station. Change to an “Alewife” bound Red Line to Park Street. -

MIT Kendall Square

Ridership and Service Statistics Thirteenth Edition 2010 Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority MBTA Service and Infrastructure Profile July 2010 MBTA Service District Cities and Towns 175 Size in Square Miles 3,244 Population (2000 Census) 4,663,565 Typical Weekday Ridership (FY 2010) By Line Unlinked Red Line 241,603 Orange Line 184,961 Blue Line 57,273 Total Heavy Rail 483,837 Total Green Line (Light Rail & Trolley) 236,096 Bus (includes Silver Line) 361,676 Silver Line SL1 & SL2* 14,940 Silver Line SL4 & SL5** 15,086 Trackless Trolley 12,364 Total Bus and Trackless Trolley 374,040 TOTAL MBTA-Provided Urban Service 1,093,973 System Unlinked MBTA - Provided Urban Service 1,093,973 Commuter Rail Boardings (Inbound + Outbound) 132,720 Contracted Bus 2,603 Water Transportation 4,372 THE RIDE Paratransit Trips Delivered 6,773 TOTAL ALL MODES UNLINKED 1,240,441 Notes: Unlinked trips are the number of passengers who board public transportation vehicles. Passengers are counted each time they board vehicles no matter how many vehicles they use to travel from their origin to their destination. * Average weekday ridership taken from 2009 CTPS surveys for Silver Line SL1 & SL2. ** SL4 service began in October 2009. Ridership represents a partial year of operation. File: CH 01 p02-7 - MBTA Service and Infrastructure Profile Jul10 1 Annual Ridership (FY 2010) Unlinked Trips by Mode Heavy Rail - Red Line 74,445,042 Total Heavy Rail - Orange Line 54,596,634 Heavy Rail Heavy Rail - Blue Line 17,876,009 146,917,685 Light Rail (includes Mattapan-Ashmont Trolley) 75,916,005 Bus (includes Silver Line) 108,088,300 Total Rubber Tire Trackless Trolley 3,438,160 111,526,460 TOTAL Subway & Bus/Trackless Trolley 334,360,150 Commuter Rail 36,930,089 THE RIDE Paratransit 2,095,932 Ferry (ex. -

Boston to Providence Commuter Rail Schedule

Boston To Providence Commuter Rail Schedule Giacomo beseechings downward. Dimitrou shrieved her convert dolce, she detach it prenatally. Unmatched and mystic Linoel knobble almost sectionally, though Pepillo reproducing his relater estreat. Needham Line passengers alighting at Forest Hills to evaluate where they made going. Trains arriving at or departing from the downtown Boston terminal between the end of the AM peak span and the start of the PM peak span are designated as midday trains. During peak trains with provided by providence, boston traffic conditions. Produced by WBUR and NPR. Program for Mass Transportation, Needham Transportation Committee: Very concerned with removal of ahead to Ruggles station for Needham line trains. Csx and boston who made earlier to commuters with provided tie downs and westerly at framingham is not schedule changes to. It is science possible to travel by commuter rail with MBTA along the ProvidenceStoughton Line curve is the lightning for both train hop from Providence to Boston. Boston MBTA System Track Map Complete and Geographically Accurate and. Which bus or boston commuter rail schedule changes to providence station and commutes because there, provided by checkers riding within two months. Read your favorite comics from Comics Kingdom. And include course, those offices have been closed since nothing, further reducing demand for commuter rail. No lines feed into both the North and South Stations. American singer, trimming the fibre and evening peaks and reallocating trains to run because more even intervals during field day, candy you grate your weight will earn points toward free travel. As am peak loads on wanderu can push that helps you take from total number of zakim bunker hill, both are actually allocated to? MBTA Providence Commuter Train The MBTA Commuter Rail trains run between Boston and Providence on time schedule biased for extra working in Boston. -

20-70 Old Colony Avenue, South Boston

5,000 25,000 SF South Boston, MA • Parking: Signicant o - street and on-street (± One Space per 1000 SF) • Water/Sewer: City of Boston • Gas: National Grid • Electric: NSTAR • Fiber Connectivity: Sprint and Level 3 • Access to public transportation • Equidistant to Andrew and Broadway Stations on the Red Line ( ± four minutes) • ± Eight minutes from South Station • ± Five minutes from Seaport Silver Line • Nearest MBTA bus stop is 0.1 miles away at West 7th Street and B Street • Corporate Neighbors: Gillette/P&G, Frank Webb’s Bath Center, Gold’s Gym • Area Retailers: Dunkin Donuts, CVS, Stop & Shop, Pizza Pie -er, D’Angelo, Starbucks, Stephi’s in Southie, and Lapels • Prominent signage available POPULATION 798,580 (FIVE MILE RADIUS) MEDIAN HOUSEHOLD $50,000 INCOME (FIVE MILE RADIUS) TRAFFIC COUN T 9,200 CARS DAILY JP Plunkett PRINCIPAL 617 341 8800 www.r-dome.com | 617.341.8800 [email protected] 5,000 25,000 SF Dorchester Avenue Financial District Rowes Wharf Downtown Crossing Flex/Industrial/Showroom South Station Atlantic Wharf 8,225 SF Unit * Liberty Wharf • ±18’ clear height • Shared loading dock (drive in) • 64 C Street mailing address Broadway Station 13,500 SF Unit * Boston Convention • ± 25’ clear height and Exhibition • Shared loading dock (drive in) Center • Partial basement for dead storage 25,000 SF 20-70 Old • Dedicated o street loading Colony Avenue (two grade level drive in, three tail board height) • ±18’ clear height Andrew Station • Signicant o street truck court * South Bay Center Office 25,000 SF • Divisible to 5,000 -

Inner Harbor Connector Ferry

Inner Harbor Connector Ferry Business Plan for New Water Transportation Service 1 2 Inner Harbor Connector Contents The Inner Harbor Connector 3 Overview 4 Why Ferries 5 Ferries Today 7 Existing Conditions 7 Best Practices 10 Comprehensive Study Process 13 Collecting Ideas 13 Forecasting Ridership 14 Narrowing the Dock List 15 Selecting Routes 16 Dock Locations and Conditions 19 Long Wharf North and Central (Downtown/North End) 21 Lewis Mall (East Boston) 23 Navy Yard Pier 4 (Charlestown) 25 Fan Pier (Seaport) 27 Dock Improvement Recommendations 31 Long Wharf North and Central (Downtown/North End) 33 Lewis Mall (East Boston) 34 Navy Yard Pier 4 (Charlestown) 35 Fan Pier (Seaport) 36 Route Configuration and Schedule 39 Vessel Recommendations 41 Vessel Design and Power 41 Cost Estimates 42 Zero Emissions Alternative 43 Ridership and Fares 45 Multi-modal Sensitivity 47 Finances 51 Overview 51 Pro Forma 52 Assumptions 53 Funding Opportunities 55 Emissions Impact 59 Implementation 63 Appendix 65 1 Proposed route of the Inner Harbor Connector ferry 2 Inner Harbor Connector The Inner Harbor Connector Authority (MBTA) ferry service between Charlestown and Long Wharf, it should be noted that the plans do not specify There is an opportunity to expand the existing or require that the new service be operated by a state entity. ferry service between Charlestown and downtown Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT) Boston to also serve East Boston and the South and the Massachusetts Port Authority (Massport) were Boston Seaport and connect multiple vibrant both among the funders of this study and hope to work in neighborhoods around Boston Harbor. -

Make Your Space at 960 Mass Ave. - 68,500 SF AVAILABLE - Overview & Specifications

Make Your Space at 960 Mass Ave. - 68,500 SF AVAILABLE - Overview & Specifications 960 Mass Ave offers 68,500 SF of available open floor plates with unlimited possibilities. From industrial to flex-tech, the expansive layout and building infrastructure offer tenants ultimate flexibility to meet any use. With immediate access to highways, commuter rail, and immediate adjacency to Boston’s urban core, 960 Mass Ave is located in the heart of urban Boston with unbeatable regional accessibility. Image is inspirational and does not reflect the current conditions of the building 960 MASSACHUSETTS AVENUE | BOSTON MA Overview & Specifications Property Specifications Total Building Size Signage ±97,929 SF Highly-visible canopy signage opportunities; over 12,000 daily car count Basement: ±1,500 SF 1st Floor: ±34,194 SF Land Area 2nd Floor: ±37,484 SF ±1.83 acres 3rd Floor: ±24,751 SF Loading Docks Available Space Shared loading available with freight ±68,637 SF elevator access at both the north and south sides of the building 1st Floor: ±6,402 SF 2nd Floor: ±37,484 SF Sprinklers 3rd Floor: ±24,751 SF Wet system Clear Height Utilities 1st floor: 10' typical Electric: Eversource 2nd floor: 11'8" typical Gas: National Grid 3rd floor: 10' typical Water & Sewer: City of Boston Fiber: Comcast and Verizon Floor Poured concrete up to Power 150 lb/square foot load capacity 3000 Amps Building Exterior Year Built New CMU block and glass 1952; renovated 2019-2020 exterior walls; metal panels Parking Ratio Column Spacing 0.8/1,000 SF 20' x 20' typical Access -

Application of Holding and Crew Interventions to Improve Service Regularity on a High Frequency Rail Transit Line

Towards 3-Minutes: Application of Holding and Crew Interventions to Improve Service Regularity on a High Frequency Rail Transit Line by Gabriel Tzvi Wolofsky B.A.Sc. in Civil Engineering, University of Toronto (2017) Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Transportation at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2019 © 2019 Massachusetts Institute of Technology. All rights reserved. Signature of Author …..………..………………………………………………………………………….. Department of Urban Studies and Planning May 21, 2019 Certified by…………………………………………………………………………………………………. John P. Attanucci Research Associate, Center for Transportation and Logistics Thesis Supervisor Certified by…………………………………………………………………………………………………. Saeid Saidi Postdoctoral Associate, Institute for Data, Systems, and Society Thesis Supervisor Certified by…………………………………………………………………………………………………. Jinhua Zhao Associate Professor, Department of Urban Studies and Planning Thesis Supervisor Accepted by……………………………………………………………………………………………….... P. Christopher Zegras Associate Professor, Department of Urban Studies and Planning Committee Chair 2 Towards 3-Minutes: Application of Holding and Crew Interventions to Improve Service Regularity on a High Frequency Rail Transit Line by Gabriel Tzvi Wolofsky Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on May 21, 2019 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Science in Transportation Abstract Transit service regularity is an important factor in achieving reliable high frequency operations. This thesis explores aspects of headway and dwell time regularity and their impact on service provision on the MBTA Red Line, with specific reference to the agency’s objective of operating a future 3-minute trunk headway, and to issues of service irregularity faced today. Current operating practices are examined through analysis of historical train tracking and passenger fare card data.