(2008) Raise the White Flag: Conflict and Collaboration in Alsace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Murder in Aubagne: Lynching, Law, and Justice During the French

This page intentionally left blank Murder in Aubagne Lynching, Law, and Justice during the French Revolution This is a study of factions, lynching, murder, terror, and counterterror during the French Revolution. It examines factionalism in small towns like Aubagne near Marseille, and how this produced the murders and prison massacres of 1795–1798. Another major theme is the conver- gence of lynching from below with official terror from above. Although the Terror may have been designed to solve a national emergency in the spring of 1793, in southern France it permitted one faction to con- tinue a struggle against its enemies, a struggle that had begun earlier over local issues like taxation and governance. This study uses the tech- niques of microhistory to tell the story of the small town of Aubagne. It then extends the scope to places nearby like Marseille, Arles, and Aix-en-Provence. Along the way, it illuminates familiar topics like the activity of clubs and revolutionary tribunals and then explores largely unexamined areas like lynching, the sociology of factions, the emer- gence of theories of violent fraternal democracy, and the nature of the White Terror. D. M. G. Sutherland received his M.A. from the University of Sussex and his Ph.D. from the University of London. He is currently professor of history at the University of Maryland, College Park. He is the author of The Chouans: The Social Origins of Popular Counterrevolution in Upper Brittany, 1770–1796 (1982), France, 1789–1815: Revolution and Counterrevolution (1985), and The French Revolution, 1770– 1815: The Quest for a Civic Order (2003) as well as numerous scholarly articles. -

Luxembourg Resistance to the German Occupation of the Second World War, 1940-1945

LUXEMBOURG RESISTANCE TO THE GERMAN OCCUPATION OF THE SECOND WORLD WAR, 1940-1945 by Maureen Hubbart A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS Major Subject: History West Texas A&M University Canyon, TX December 2015 ABSTRACT The history of Luxembourg’s resistance against the German occupation of World War II has rarely been addressed in English-language scholarship. Perhaps because of the country’s small size, it is often overlooked in accounts of Western European History. However, Luxembourgers experienced the German occupation in a unique manner, in large part because the Germans considered Luxembourgers to be ethnically and culturally German. The Germans sought to completely Germanize and Nazify the Luxembourg population, giving Luxembourgers many opportunities to resist their oppressors. A study of French, German, and Luxembourgian sources about this topic reveals a people that resisted in active and passive, private and public ways. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Elizabeth Clark for her guidance in helping me write my thesis and for sharing my passion about the topic of underground resistance. My gratitude also goes to Dr. Brasington for all of his encouragement and his suggestions to improve my writing process. My thanks to the entire faculty in the History Department for their support and encouragement. This thesis is dedicated to my family: Pete and Linda Hubbart who played with and took care of my children for countless hours so that I could finish my degree; my husband who encouraged me and always had a joke ready to help me relax; and my parents and those members of my family living in Europe, whose history kindled my interest in the Luxembourgian resistance. -

Krafft to Niderviller

Panache Classic Alsace & Lorraine Cruise Krafft to Niderviller ITINERARY Sunday, Day 1 Krafft Guests are met in Strasbourg** and transferred by private chauffeured minibus to Panache for a Champagne welcome and the first opportunity to meet your crew. Perhaps there is time for a walk or cycle ride before dinner on board. Monday, Day 2 Krafft to Strasbourg Our day starts with a morning cruise, across the Gran Ried wetlands and home to an abundance of birdlife, to arrive at the historic city of Strasbourg. Later, we enjoy a tour of the beautiful ‘capital city of Europe’ including, of course, a visit to the 12th century Gothic pink sandstone cathedral, home to an astronomical Renaissance clock and soaring spire. We visit Place Gutenberg and explore La Petite France, a pedestrian area brimming with half-timbered houses, boutique shops and cafés. Dinner on board. Tuesday, Day 3 Strasbourg to Waltenheim-sur-Zorn After breakfast, our cruise takes us past the impressive European Parliament building on the outskirts of Strasbourg and on through the Brumath Forest to our picturesque mooring at Waltenheim-sur-Zorn. This afternoon we enjoy a scenic drive into the rolling Vosges hills on the Route des Grands Vins, where the finest wines of Alsace are produced, and a private tasting of Gewürztraminer, Pinot Noir and Riesling wines at a long-established winemaker, such as Domaine Pfister. Dinner ashore this evening at a traditional Alsatian restaurant. Wednesday, Day 4 Waltenheim-sur-Zorn to Saverne This morning, for any guests who are interested we can arrange a guided tour, with an optional beer tasting, of the Meteor Brewery, the last privately-owned brewery in Alsace. -

Le Canal De La Marne Au Rhin

CANAUX ET VÉLOROUTES D’ALSACE Wasserwege und Fernradwege im Elsass Waterways and Cycle routes in Alsace Waterwegen en Fietspaden in de Elzas 5 Sarre-UnionLe canal de la Marne au Rhin | 86 km 3.900 KM 4 km EUROVÉLO 5 : Harskirchen (Section Réchicourt > Strasbourg)(Abschnitt Réchicourt > Straßburg) 17 km (Section Réchicourt > Strasbourg) Sarrewerden Der Rhein Marne Kanal Ecluse 16 /Altviller 16 The Rhine-Marne canal(stuk Réchicourt > Straatsburg) 5 Marne-Rijnkanaal PARC NATUREL 2H30 Diedendorf RÉGIONAL 13 km 14 ALSACE BOSSUE DES VOSGES DU NORD HAGUENAU Mittersheim 13 Fénétrange Schwindratzheim 10,7 km 64 Mutzenhouse Bischwil St-Jean-de-Bassel 11,5 km 6 H 20 km Niederschaeffolsheim Albeschaux Steinbourg Waltenheim 5 H Hochfelden 87 2H 44 sur Zorn Henridorff 37 Rhodes Langatte 41 en cana SAVERNE 4,3 km Brumath nci l 4,8 km A liger Ka ma na 5 km 1 SARREBOURG e er can l 8,2 km 4 h rm al 20 3 H 30 11 km e o F 31 Zornhoff Dettwiller 3H30 6,5 km Monswiller Lupstein Wingersheim Niderviller Vendenheim Kilstett 10 km 5 H Houillon Lutzelbourg Mittelhausen Reichstett Arzviller Saint-Louis 5 km GONDREXANGE 2H45 Guntzviller Marmoutier 2H30 Plaine-de-Walsch Souffelweyersheim 18 Hesse Hohatzenheim 3,8 km Xouaxange Bischheim La Landange 1H15 RÉCHICOURT Schiltigheim KOCHERSBERG 51 15,8 km 15,8 5 km 15,8 Kehl 6 9 km 857 Offe STRASBOURG 85 Bas-Rhin 1 2 3 5 6 7 LORRAINE (F) 9,2 km LOTHRINGEN 2H30 Neuried (D) PFALZ (D) Lauterbourg 6,7 km BAS-RHIN Plobsheim ALSACE 1H Réchicourt Strasbourg LORRAINE 3 km 80 BADENKrafft Colmar SCHWARZWALD (D) Fribourg (DE) Mulhouse -

“Politics, Ballyhoo, and Controversy”: the Allied Clandestine Services, Resistance, and the Rivalries in Occupied France

“Politics, Ballyhoo, and Controversy”: The Allied Clandestine Services, Resistance, and the Rivalries in Occupied France By Ronald J. Lienhardt History Departmental Undergraduate Honors Thesis University of Colorado at Boulder April 8, 2014 Thesis Advisor: Dr. Martha Hanna Department of History Defense Committee: Dr. John Willis Department of History Dr. Michael Radelet Department of Sociology 1 Song of the Partisans By Maurice Druon Friend, can you hear The Flight of the ravens Over our plains? Friend, can you hear The muffled cry of our country In chains? Ah! Partisans, Workers and peasants, The alert has sounded. This evening the enemy Will learn the price of blood And of tears.1 1 Claude Chambard, The Maquis: A History of the French Resistance Movement (New York: The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc. , 1976), vii. 2 Table of Contents Abstract---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------4 Introduction--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------5 Chapter 1: Impending War, the fall of France, and the Foundations of Resistance---------------------8 France’s Initiative becomes outdated: The Maginot Line-------------------------------------------------------11 Failures to Adapt to the Progress of War: The Invasion and the fall of France----------------------------14 Collaboration and Life Under Occupation-------------------------------------------------------------------------20 Organization -

Alsace (Short Stays)

Follow Locaboat Holidays on: Alsace Navigation Guide Helpful tip: download a QRCode App Ahoy, captains! Create your own route.. www.locaboat.com 11 Week-ends and Short Weeks (mini-weeks) Week-ends Short Weeks www.locaboat.com 22 Lock Operating Hours : * Until 6 p.m. in July and August - Closed on May 1st The locks on the Marne-Rhine Canal, the Sarre Canal and the Vosges Canal are automatic and are operated by the Lock keepers themselves. Lower a crew member ashore before the lock to walk to the controls. Entry into the lock takes place when the green signal is indicated. Your crew member should always stay by the control panel during the lock passage, ready to press the red stop button in the event of an emergency. Moselle locks are automatic and operated by lock keepers, permanent or touring. It is preferable to lower a crew member ashore before the lock, so that they can receive the mooring ropes once the boat is in the lock. Do not hesitate to consult our tutorial with the following link: www.youtube.com/watch?v=86u8vRiGjkE www.locaboat.com 3 Quick History Points: Plan incliné d'arzviller (Arzviller boat lift): Le chateau des Rohans (Rohans Castle) : The Plan Incliné of Saint-Louis Arzviller is a boat The majestic Château des Rohan, with its immense lift/elevator, unique in Europe, which has been in neoclassical facade, offers testimony to the role of service since January 27th, 1969. Situated on the Saverne. Since the beginning of the Middle Ages, Canal de la Marne-au-Rhin, it lets you cross the the town has been the property of the Strasbourg threshold of the Vosges mountains by river. -

Supplementary Information for Ancient Genomes from Present-Day France

Supplementary Information for Ancient genomes from present-day France unveil 7,000 years of its demographic history. Samantha Brunel, E. Andrew Bennett, Laurent Cardin, Damien Garraud, Hélène Barrand Emam, Alexandre Beylier, Bruno Boulestin, Fanny Chenal, Elsa Cieselski, Fabien Convertini, Bernard Dedet, Sophie Desenne, Jerôme Dubouloz, Henri Duday, Véronique Fabre, Eric Gailledrat, Muriel Gandelin, Yves Gleize, Sébastien Goepfert, Jean Guilaine, Lamys Hachem, Michael Ilett, François Lambach, Florent Maziere, Bertrand Perrin, Susanne Plouin, Estelle Pinard, Ivan Praud, Isabelle Richard, Vincent Riquier, Réjane Roure, Benoit Sendra, Corinne Thevenet, Sandrine Thiol, Elisabeth Vauquelin, Luc Vergnaud, Thierry Grange, Eva-Maria Geigl, Melanie Pruvost Email: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], Contents SI.1 Archaeological context ................................................................................................................. 4 SI.2 Ancient DNA laboratory work ................................................................................................... 20 SI.2.1 Cutting and grinding ............................................................................................................ 20 SI.2.2 DNA extraction .................................................................................................................... 21 SI.2.3 DNA purification ................................................................................................................. 22 SI.2.4 -

Oil HERRLISHEIM by C CB·;-:12Th Arind

i• _-f't,, f . ._,. ... :,.. ~~ :., C ) The Initial Assault- "Oil HERRLISHEIM by C_CB·;-::12th Arind Div ) i ,, . j.. ,,.,,\, .·~·/ The initial assault on Herrli sheim by CCB, ' / 12th Armored Division. Armored School, student research report. Mar 50. ~ -1 r 2. 1 J96§ This Docuntent IS A HOLDING OF THE ARCHIVES SECTION LIBRARY SERVICES FORT LEAVENWORTH, KANSAS I . DOCUMENT NO. N- 2146 .46 COPY NO. _!_ ' A RESEARCH REPORT Prepared at THE ARMORED SCHOOL Fort Knox Kentucky 1949- 1950 <re '4 =#= f 1 , , R-5 01 - □ 8 - I 'IHE INITIAL ASSAULT ON HERRLISHEIM BY COMBAT COMMAND B, 12th ARMORED DIVISION A RESEARCH REPORT PREPARED BY COI\AMITTEE 7, OFFICERS ADVANCED ~OUR.SE THE ARMORED SCHOOL 1949-1950 LIEUTENANT COLONEL GAYNOR vi. HATHNJAY MAJOR "CLARENCE F. SILLS MAJOR LEROY F, CLARK MAJOR GEORGE A. LUCEY ( MAJ OR HAROLD H. DUNvvOODY MAJ OR FRANK J • V IDLAK CAPTAIN VER.NON FILES CAPTAIN vHLLIAM S. PARKINS CAPTAIN RALPH BROWN FORT KNCOC, KENTlCKY MARCH 1950 FOREtfORD Armored warfare played a decisive role in the conduct of vforld War II. The history of th~ conflict will reveal the outstanding contri bution this neWcomer in the team of ground arms offered to all commartiers. Some of the more spectacular actions of now famous armored units are familiar to all students of military history. Contrary to popular be lief, however, not all armored actions consisted of deep slashing drives many miles into enemy territory. Some armored units were forced to engage in the more unspectacular slugging actions against superior enemy forces. One such action, the attack of Combat Comnand B, 12th Armored Division, against HERRLISHEIM, FRANCE, is reviewed in this paper. -

Soufflenheim Jewish Records

SOUFFLENHEIM JEWISH RECORDS Soufflenheim Genealogy Research and History www.soufflenheimgenealogy.com There are four main types of records for Jewish genealogy research in Alsace: • Marriage contracts beginning in 1701. • 1784 Jewish census. • Civil records beginning in 1792. • 1808 Jewish name declaration records. Inauguration of a synagogue in Alsace, attributed to Georg Emmanuel Opitz (1775-1841), Jewish Museum of New York. In 1701, Louis XIV ordered all Jewish marriage contracts to be filed with Royal Notaries within 15 days of marriage. Over time, these documents were registered with increasing frequency. In 1784, Louis XVI ordered a general census of all Jews in Alsace. Jews became citizens of France in 1791 and Jewish civil registration begins from 1792 onwards. To avoid problems raised by the continuous change of the last name, Napoleon issued a Decree in 1808 ordering all Jews to adopt permanent family names, a practice already in use in some places. In every town where Jews lived, the new names were registered at the Town Hall. They provide a comprehensive census of the French Jewish population in 1808. Keeping registers of births, marriage, and deaths is not part of the Jewish religious tradition. For most people, the normal naming practice was to add the father's given name to the child's. An example from Soufflenheim is Samuel ben Eliezer whose father is Eliezer ben Samuel or Hindel bat Eliezer whose father is Eliezer ben Samuel (ben = son of, bat = daughter of). Permanent surnames were typically used only by the descendants of the priests (Kohanim) and Levites, a Jewish male whose descent is traced to Levi. -

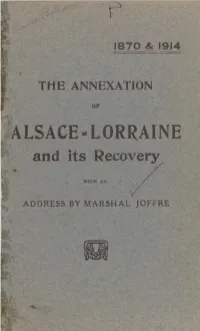

ALSACE-LORRAINE and Its Recovery

1870 & 1914 THE ANNEXATION OP ALSACE-LORRAINE and its Recovery WI.1M AN ADDRESS BY MARSHAL JOFFRE THE ANNEXATION OF ALSACE-LORRAINE and its Recovery 1870 & 1914 THE ANNEXATION OF ALSACE=LORRA1NE and its Recovery WITH AN ADDRESS BY MARSHAL JOFFRE PARIS IMPRIMERIE JEAN CUSSAC 40 — RUE DE REUILLY — 40 I9I8 ADDRESS in*" MARSHAL JOFFRE AT THANN « WE HAVE COME BACK FOR GOOD AND ALL : HENCEFORWARD YOU ARE AND EVER WILL BE FRENCH. TOGETHER WITH THOSE LIBERTIES FOR WHICH HER NAME HAS STOOD THROUGHOUT THE AGES, FRANCE BRINGS YOU THE ASSURANCE THAT YOUR OWN LIBERTIES WILL BE RESPECTED : YOUR ALSATIAN LIBER- TIES, TRADITIONS AND WAYS OF LIVING. AS HER REPRESENTATIVE I BRING YOU FRANCE'S MATERNAL EMBRACE. » INTRODUCTION The expression Alsace-Lorraine was devis- ed by the Germans to denote that part of our national territory, the annexation of which Germany imposed upon us by the treaty of Frankfort, in 1871. Alsace and Lorraine were the names of two provinces under our monarchy, but provinces — as such — have ceased to exi$t in France since 1790 ; the country is divided into depart- ments — mere administrative subdivisions under the same national laws and ordi- nances — nor has the most prejudiced his- torian ever been able to point to the slight- est dissatisfaction with this arrangement on the part of any district in France, from Dunkirk to Perpignan, or from Brest to INTRODUCTION Strasbourg. France affords a perfect exam- ple of the communion of one and all in deep love and reverence for the mother-country ; and the history of the unfortunate depart- ments subjected to the yoke of Prussian militarism since 1871 is the most eloquent and striking confirmation of the justice of France's demand for reparation of the crime then committed by Germany. -

Introduction

Cambridge University Press 0521836182 - Nobles and Nation in Central Europe: Free Imperial Knights in the Age of Revolution, 1750-1850 William D. Godsey Excerpt More information Introduction “The Free Imperial Knights are an immediate corpus of the German Empire that does not have, to be sure, a vote or a seat in imperial assemblies, but by virtue of the Peace of Westphalia, the capitulations at imperial elections, and other imperial laws exercise on their estates all the same rights and jurisdiction as the high nobility (Reichsstande¨ ).” Johann Christian Rebmann, “Kurzer Begriff von der Verfassung der gesammten Reichsritterschaft,” in: Johann Mader, ed., Reichsritterschaftliches Magazin, vol. 3 (Frankfurt am Main and Leipzig, 1783), 564. Two hundred years have now passed since French revolutionary armies, the Imperial Recess of 1803 (Reichsdeputationshauptschluß ), and the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806 ended a matchless and seamless noble world of prebends, pedigrees, provincial Estates, and orders of knighthood in much of Central Europe.Long-forgotten secular collegiate foundations for women in Nivelles (Brabant), Otmarsheim (Alsace), Bouxieres-aux-` Dames (Lorraine), Essen, Konstanz, and Prague were as much a part of it as those for men at St.Alban in Mainz, St.Ferrutius in Bleidenstadt, and St.Burkard in W urzburg.The¨ blue-blooded cathedral chapters of the Germania Sacra were scattered from Liege` and Strasbourg to Speyer and Bamberg to Breslau and Olmutz.Accumulations¨ in one hand of canonicates in Bamberg, Halberstadt, and Passau or Liege,` Trier, and Augsburg had become common.This world was Protestant as well as Catholic, with some chapters, the provincial diets, and many secular collegiate foundations open to one or both confessions.Common to all was the early modern ideal of nobility that prized purity above antiquity, quarterings above patrocliny, and virtue above ethnicity. -

Biblical Republicanism and the Emancipation of Jews in Revolutionary France

W&M ScholarWorks Arts & Sciences Articles Arts and Sciences 5-1994 Translating the Marseillaise: Biblical Republicanism and the Emancipation of Jews in Revolutionary France Ronald Schechter College of William and Mary, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/aspubs Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Schechter, Ronald, Translating the Marseillaise: Biblical Republicanism and the Emancipation of Jews in Revolutionary France (1994). Past and Present, 143, 108-135. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/aspubs/783 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts and Sciences at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Articles by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. On 21 October 1792 the Jews of Metz joined their Gentile compatriots in celebrating a republican victory. Emancipated by the Constituent Assembly only one year previously, the newcomers to French citizenship took the occasion of a civic festival to celebrate their recently won freedom. Testimony to this public show of Jewish patriotic zeal is an extraordinary document, a Hebrew version of the "Marseillaise," which the "citizens professing the faith of Moses" sang to republican soldiers in the synagogue of Metz. There was nothing blasphemous in the patriotic hymn, and indeed the Jews were following an ancient tradition by praying for the land to which they had been dispersed. For the period of the Revolution, however, it was an unique event, and as such provides the historian with a rare opportunity to glimpse into the world of French Jewry on the morrow of its emancipation.