Bruno Von Rappoltstein: Power Relationships in Later Medieval Alsace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bulletin Du Centre D'études Médiévales

Bulletin du centre d’études médiévales d’Auxerre | BUCEMA 22.1 | 2018 Varia Alsace and Burgundy : Spatial Patterns in the Early Middle Ages, c. 600-900 Karl Weber Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/cem/14838 DOI: 10.4000/cem.14838 ISSN: 1954-3093 Publisher Centre d'études médiévales Saint-Germain d'Auxerre Electronic reference Karl Weber, « Alsace and Burgundy : Spatial Patterns in the Early Middle Ages, c. 600-900 », Bulletin du centre d’études médiévales d’Auxerre | BUCEMA [Online], 22.1 | 2018, Online since 03 September 2018, connection on 19 April 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/cem/14838 ; DOI : 10.4000/ cem.14838 This text was automatically generated on 19 April 2019. Les contenus du Bulletin du centre d’études médiévales d’Auxerre (BUCEMA) sont mis à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d’Utilisation Commerciale - Partage dans les Mêmes Conditions 4.0 International. Alsace and Burgundy : Spatial Patterns in the Early Middle Ages, c. 600-900 1 Alsace and Burgundy : Spatial Patterns in the Early Middle Ages, c. 600-900 Karl Weber EDITOR'S NOTE Cet article fait référence aux cartes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 8 et 10 du dossier cartographique. Ces cartes sont réinsérées dans le corps du texte et les liens vers le dossier cartographique sont donnés en documents annexes. Bulletin du centre d’études médiévales d’Auxerre | BUCEMA, 22.1 | 2018 Alsace and Burgundy : Spatial Patterns in the Early Middle Ages, c. 600-900 2 1 The following overview concerns the question of whether forms of spatial organisation below the kingdom level are discernible in the areas corresponding to present-day Western Switzerland and Western France during the early Middle Ages. -

Treaty of Westphalia

Background Information Treaty of Westphalia The Peace of Westphalia, also known as the Treaty of Münster and the Treaty of Osnabrück, refers to a pair of treaties that ended the Thirty Years' War and officially recognized the Dutch Republic and Swiss Confederation. • The Spanish treaty that ended the Thirty Years' War was signed on January 30, 1648. • A treaty between the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand III, the other German princes and the representatives from the Dutch Republic, France and Sweden was signed on October 24, 1648. • The Treaty of the Pyrenees, signed in 1659, ending the war between France and Spain, is also often considered part of this treaty. The Peace of Westphalia is the first international agreement to acknowledge a country's sovereignty and is thus thought to mark the beginning of the modern system of nation- states (Westphalian states). The majority of the treaty's terms can be attributed to the work of Cardinal Mazarin, the de facto leader of France at the time (the King, Louis XIV, was still a child). France came out of the war in a far better position than any of the other powers and was able to dictate much of the treaty. The results of the treaty were wide ranging. Among other things, the Netherlands now officially gained independence from Spain, ending the Eighty Years' War, and Sweden gained Pomerania, Wismar, Bremen and Verden. The power of the Holy Roman Emperor was broken and the rulers of the German states were again able to determine the religion of their lands. The treaty also gave Calvinists legal recognition. -

Soufflenheim Jewish Records

SOUFFLENHEIM JEWISH RECORDS Soufflenheim Genealogy Research and History www.soufflenheimgenealogy.com There are four main types of records for Jewish genealogy research in Alsace: • Marriage contracts beginning in 1701. • 1784 Jewish census. • Civil records beginning in 1792. • 1808 Jewish name declaration records. Inauguration of a synagogue in Alsace, attributed to Georg Emmanuel Opitz (1775-1841), Jewish Museum of New York. In 1701, Louis XIV ordered all Jewish marriage contracts to be filed with Royal Notaries within 15 days of marriage. Over time, these documents were registered with increasing frequency. In 1784, Louis XVI ordered a general census of all Jews in Alsace. Jews became citizens of France in 1791 and Jewish civil registration begins from 1792 onwards. To avoid problems raised by the continuous change of the last name, Napoleon issued a Decree in 1808 ordering all Jews to adopt permanent family names, a practice already in use in some places. In every town where Jews lived, the new names were registered at the Town Hall. They provide a comprehensive census of the French Jewish population in 1808. Keeping registers of births, marriage, and deaths is not part of the Jewish religious tradition. For most people, the normal naming practice was to add the father's given name to the child's. An example from Soufflenheim is Samuel ben Eliezer whose father is Eliezer ben Samuel or Hindel bat Eliezer whose father is Eliezer ben Samuel (ben = son of, bat = daughter of). Permanent surnames were typically used only by the descendants of the priests (Kohanim) and Levites, a Jewish male whose descent is traced to Levi. -

DIE FORMIERUNG DES ELSASS IM REGNUM FRANCORUM, Archuge

Karl Weber DIE FORMIERUNG DES ELSASS IM REGNUM FRANCORUM ARCHÄOLOGIE UND GESCHICHTE Freiburger Forschungen zum ersten Jahrtausend in Südwestdeutschland Herausgegeben von Hans Ulrich Nuber, Karl Schmid†, Heiko Steuer und Thomas Zotz Band 19 Karl Weber DieFormierungdesElsass imRegnumFrancorum Adel, Kirche und Königtum am Oberrhein in merowingischer und frühkarolingischer Zeit Gedruckt mit Unterstützung der Geschwister Boehringer Ingelheim Stiftung für Geisteswissenschaften in Ingelheim am Rhein Für die Schwabenverlag AG ist Nachhaltigkeit ein wichtiger Maßstab ihres Handelns. Wir achten daher auf den Einsatz umweltschonender Ressourcen und Materialien. Dieses Buch wurde auf FSC®-zertifiziertem Papier gedruckt. FSC (Forest Stewardship Council®) ist eine nicht staatliche, gemeinnützige Organisation, die sich für eine ökologische und sozial verantwortliche Nutzung der Wälder unserer Erde einsetzt. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbiblio- grafie; detaillierte bibliographische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Alle Rechte vorbehalten © 2011 Jan Thorbecke Verlag der Schwabenverlag AG, Ostfildern www.thorbecke.de Umschlaggestaltung: Finken+Bumiller, Stuttgart Umschlagabbildung: St. Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. Sang. 551 p. 106: Beginn der Passio S. Germani Satz: Karlheinz Hülser, Konstanz Druck: Memminger MedienCentrum, Memmingen Hergestellt in Deutschland ISBN 978-3-7995-7369-6 Inhalt Vorwort ........................................................ -

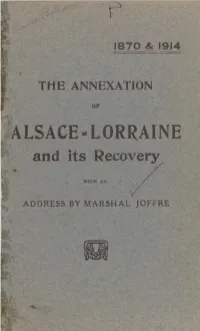

ALSACE-LORRAINE and Its Recovery

1870 & 1914 THE ANNEXATION OP ALSACE-LORRAINE and its Recovery WI.1M AN ADDRESS BY MARSHAL JOFFRE THE ANNEXATION OF ALSACE-LORRAINE and its Recovery 1870 & 1914 THE ANNEXATION OF ALSACE=LORRA1NE and its Recovery WITH AN ADDRESS BY MARSHAL JOFFRE PARIS IMPRIMERIE JEAN CUSSAC 40 — RUE DE REUILLY — 40 I9I8 ADDRESS in*" MARSHAL JOFFRE AT THANN « WE HAVE COME BACK FOR GOOD AND ALL : HENCEFORWARD YOU ARE AND EVER WILL BE FRENCH. TOGETHER WITH THOSE LIBERTIES FOR WHICH HER NAME HAS STOOD THROUGHOUT THE AGES, FRANCE BRINGS YOU THE ASSURANCE THAT YOUR OWN LIBERTIES WILL BE RESPECTED : YOUR ALSATIAN LIBER- TIES, TRADITIONS AND WAYS OF LIVING. AS HER REPRESENTATIVE I BRING YOU FRANCE'S MATERNAL EMBRACE. » INTRODUCTION The expression Alsace-Lorraine was devis- ed by the Germans to denote that part of our national territory, the annexation of which Germany imposed upon us by the treaty of Frankfort, in 1871. Alsace and Lorraine were the names of two provinces under our monarchy, but provinces — as such — have ceased to exi$t in France since 1790 ; the country is divided into depart- ments — mere administrative subdivisions under the same national laws and ordi- nances — nor has the most prejudiced his- torian ever been able to point to the slight- est dissatisfaction with this arrangement on the part of any district in France, from Dunkirk to Perpignan, or from Brest to INTRODUCTION Strasbourg. France affords a perfect exam- ple of the communion of one and all in deep love and reverence for the mother-country ; and the history of the unfortunate depart- ments subjected to the yoke of Prussian militarism since 1871 is the most eloquent and striking confirmation of the justice of France's demand for reparation of the crime then committed by Germany. -

The Ginger Fox's Two Crowns Central Administration and Government in Sigismund of Luxembourg's Realms

Doctoral Dissertation THE GINGER FOX’S TWO CROWNS CENTRAL ADMINISTRATION AND GOVERNMENT IN SIGISMUND OF LUXEMBOURG’S REALMS 1410–1419 By Márta Kondor Supervisor: Katalin Szende Submitted to the Medieval Studies Department, Central European University, Budapest in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Medieval Studies, CEU eTD Collection Budapest 2017 Table of Contents I. INTRODUCTION 6 I.1. Sigismund and His First Crowns in a Historical Perspective 6 I.1.1. Historiography and Present State of Research 6 I.1.2. Research Questions and Methodology 13 I.2. The Luxembourg Lion and its Share in Late-Medieval Europe (A Historical Introduction) 16 I.2.1. The Luxembourg Dynasty and East-Central-Europe 16 I.2.2. Sigismund’s Election as King of the Romans in 1410/1411 21 II. THE PERSONAL UNION IN CHARTERS 28 II.1. One King – One Land: Chancery Practice in the Kingdom of Hungary 28 II.2. Wearing Two Crowns: the First Years (1411–1414) 33 II.2.1. New Phenomena in the Hungarian Chancery Practice after 1411 33 II.2.1.1. Rex Romanorum: New Title, New Seal 33 II.2.1.2. Imperial Issues – Non-Imperial Chanceries 42 II.2.2. Beginnings of Sigismund’s Imperial Chancery 46 III. THE ADMINISTRATION: MOBILE AND RESIDENT 59 III.1. The Actors 62 III.1.1. At the Travelling King’s Court 62 III.1.1.1. High Dignitaries at the Travelling Court 63 III.1.1.1.1. Hungarian Notables 63 III.1.1.1.2. Imperial Court Dignitaries and the Imperial Elite 68 III.1.1.2. -

Introduction

Cambridge University Press 0521836182 - Nobles and Nation in Central Europe: Free Imperial Knights in the Age of Revolution, 1750-1850 William D. Godsey Excerpt More information Introduction “The Free Imperial Knights are an immediate corpus of the German Empire that does not have, to be sure, a vote or a seat in imperial assemblies, but by virtue of the Peace of Westphalia, the capitulations at imperial elections, and other imperial laws exercise on their estates all the same rights and jurisdiction as the high nobility (Reichsstande¨ ).” Johann Christian Rebmann, “Kurzer Begriff von der Verfassung der gesammten Reichsritterschaft,” in: Johann Mader, ed., Reichsritterschaftliches Magazin, vol. 3 (Frankfurt am Main and Leipzig, 1783), 564. Two hundred years have now passed since French revolutionary armies, the Imperial Recess of 1803 (Reichsdeputationshauptschluß ), and the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806 ended a matchless and seamless noble world of prebends, pedigrees, provincial Estates, and orders of knighthood in much of Central Europe.Long-forgotten secular collegiate foundations for women in Nivelles (Brabant), Otmarsheim (Alsace), Bouxieres-aux-` Dames (Lorraine), Essen, Konstanz, and Prague were as much a part of it as those for men at St.Alban in Mainz, St.Ferrutius in Bleidenstadt, and St.Burkard in W urzburg.The¨ blue-blooded cathedral chapters of the Germania Sacra were scattered from Liege` and Strasbourg to Speyer and Bamberg to Breslau and Olmutz.Accumulations¨ in one hand of canonicates in Bamberg, Halberstadt, and Passau or Liege,` Trier, and Augsburg had become common.This world was Protestant as well as Catholic, with some chapters, the provincial diets, and many secular collegiate foundations open to one or both confessions.Common to all was the early modern ideal of nobility that prized purity above antiquity, quarterings above patrocliny, and virtue above ethnicity. -

The Peasants War in Germany, 1525-1526

Jioctaf JSibe of f0e (geformatton in THE PEASANTS WAR IN GERMANY ^ocmf ^i&e of flje (Betman (geformafton. BY E. BELFORT BAX. I. GERMAN SOCIETY AT THE CLOSE OF THE MIDDLE AGES. II. THE PEASANTS WAR, 15251526. III. THE RISE AND FALL OF THE ANA- BAPTISTS. [In preparation. LONDON: SWAN SONNENSCHEIN & CO., LIM. NEW YORK: THE MACMILLAN CO. 1THE PEASANTS WAR IN GERMANY// 1525-1526 BY E^BELFORT ': " AUTHOR OF " THE STORY OF THE FRENCH REVOLUTION," THE RELIGION OF SOCIALISM," "THE ETHICS OF SOCIALISM," "HANDBOOK OF THE HISTORY OF PHILOSOPHY," ETC., ETC. WITH A MAP OF GERMANY AT THE TIME OF THE REFORMATION <& LONDON SWAN SONNENSCHEIN & CO., LIM. NEW YORK: THE MACMILLAN CO. 1899 54 ABERDEEN UNIVERSITY PRESS PREFACE. IN presenting a general view of the incidents of the so-called Peasants War of 1525, the historian encounters more than one difficulty peculiar to the subject. He has, in the first place, a special trouble in preserving the true proportion in his narrative. Now, proportion is always the crux in historical work, but here, in describing a more or less spontaneous movement over a wide area, in which movement there are hundreds of differ-^/ ent centres with each its own story to tell, it is indeed hard to know at times what to include and what to leave out. True, the essential ^ similarity in the origin and course of events renders a recapitulation of the different local risings unnecessary and indeed embarrassing for readers whose aim is to obtain a general notion. But the author always runs the risk of being waylaid by some critic in ambush, who will accuse him of omitting details that should have been recorded. -

The Project Gutenberg Ebook of a History of the Reformation (Vol. 1 of 2) by Thomas M

The Project Gutenberg EBook of A History of the Reformation (Vol. 1 of 2) by Thomas M. Lindsay This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: A History of the Reformation (Vol. 1 of 2) Author: Thomas M. Lindsay Release Date: August 29, 2012 [Ebook 40615] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A HISTORY OF THE REFORMATION (VOL. 1 OF 2)*** International Theological Library A History of The Reformation By Thomas M. Lindsay, M.A., D.D. Principal, The United Free Church College, Glasgow In Two Volumes Volume I The Reformation in Germany From Its Beginning to the Religious Peace of Augsburg Edinburgh T. & T. Clark 1906 Contents Series Advertisement. 2 Dedication. 6 Preface. 7 Book I. On The Eve Of The Reformation. 11 Chapter I. The Papacy. 11 § 1. Claim to Universal Supremacy. 11 § 2. The Temporal Supremacy. 16 § 3. The Spiritual Supremacy. 18 Chapter II. The Political Situation. 29 § 1. The small extent of Christendom. 29 § 2. Consolidation. 30 § 3. England. 31 § 4. France. 33 § 5. Spain. 37 § 6. Germany and Italy. 41 § 7. Italy. 43 § 8. Germany. 46 Chapter III. The Renaissance. 53 § 1. The Transition from the Mediæval to the Modern World. 53 § 2. The Revival of Literature and Art. 56 § 3. Its earlier relation to Christianity. 59 § 4. The Brethren of the Common Lot. -

Haut-Rhin Est Limité" Au IV

DICTIONNAIRE TOPOGRAPHIQUE DK LA FRANCE COMPRENANT LES NOMS DE LIEU ANCIENS ET MODERNES PAR ORDRE DU MINISTRE DE L'INSTRUCTION PUBLIQUE H SOI S LA DIRECTION DU COMITÉ DES TRAVAUX H1STOHIQIIES ET DES SOCIÉTÉS SAVANTES. DICTIONNAIRE TOPOGRAPHIOUE DU DEPARTEMENT DU HAUT- RHIN COMPRENANT LES NOMS DE LIEU ANCIENS ET MODERNES RKDIfiÉ SOIS LES U.SPICES DR LA SOCIÉTÉ INDUSTRIELLE DE MULHOUSE PAR M. GEORGES STOFFEL MEMBRE DE CETTE SOCIETE oowuaramtun on mnnftu de l'instruction pcbliqui i>oir i.ks mu un historiques PARIS IMPRIMERIE IMPÉRIALE \i Dcc<; lxviii DC Gll INTRODUCTION. PARTIE DESCRIPTIVE. Le département du Haut-Rhin est limité" au IV. par celui du Bas-Rhin; à l'E. par le Rhin, qui le sépare de l'Allemagne; au S. par la Suisse et le département du Doubs, et à l'O. par ceux de la Haute-Saône et des Vosges. Il est situé entre les &7 2 5' et liH° 1 8' de latitude septentrionale, et entre les h" ih' et 5° 1 h' de longitude orientale du méridien de Paris. Sa plus grande longueur du nord au sud, depuis l'Allemand-Rom- bacfa jusqu'à Lucelle, est de 95 kilomètres; sa plus grande largeur, depuis Bue jusqu'à Hiiniiigue, de 60 kilomètres. D'après le cadastre, sa superficie CMnprend k\ i.->.-\'-\ hectares U ares 91 centiares, qui se subdivisent ainsi : Terra labourables i57,47o h 00* 00 e Prairies naturelles 55,696 00 00 Vergers, pépinières, jardins 5,676 00 00 ' tseraies , aunaies . saussaies 1 o4 00 00 Châtaigneraies 1,117 00 00 Landes, pâlis, bmyèius 27,824 00 00 $ \ ignés 1 1,622 17 71 Bois et forêts 113,576 00 00 Propriétés bâties 1,936 00 00 Etangs, abreuvoirs, mares, canaux d'irrigation 1,61 1 00 00 Cimetières, églises, presbytères, bâtiments publics..] Rivières, lacs, ruisseaux \ 34,790 86 5o Routes, chemins, places publiques, rues ) Total 4 11,2 2 3 o4 21 Haut-Rhin, a . -

27. Eiman / Eimen / Eymann

EIMAN 27. EIMAN / EIMEN / EYMANN The Eiman name, found in many different forms from Aymann to Eimer, belongs to a very prolific Anabaptist family in Alsace and Lorraine, France. Eiman was the common form used in Canada. Although the name is not found among Canadians of Amish-Mennonite descent today, there are many with Eymann/Eiman ancestry – most notably, the Wagler family. This EIMAN Family Genealogical Introduction will be divided into the following sections: 1. The Barbe Eymann and Isaac Wagler Family 2. The Peter Eymann Family a) The John Eiman and Barbara Goldschmidt Family (grandson) b) The Peter and Magdalena (Frutiger) Eiman Family (son) c) The Daniel and Barbara (Zehr) Eiman family (grandson) 3. The Nicholas Eyman of the “Eymann Bible” 4. Jacob Eyman THE BARBE EYMANN AND ISAAC WAGLER FAMILY The Barbe Eymann and Isaac Wagler family is listed first because so many of the present-day families in the Amish Mennonite communities in Ontario, Canada can trace their ancestry to this couple. Johannes Wagler, the father of Isaac Wagler, re-negotiated a lease on the Muesberg Farm for 18 years beginning in April 1765. Muesberg and Muesbach were the names of farms/estates on which Waglers and Eimans lived, and were located in the district of Ribeauvillé, Department of Haut Rhin (Upper Alsace). By that time Isaac Wagler was living on the Muesbach Farm and had added his signature to a lease negotiated by Peter and Nicholas Eymann in 1762. When that lease ran out, Isaac Wagler and Peter Eymann renewed the lease for the period 1781 to 1799. -

Etude INSEE Synthèse Sundgau

SCOT du Sundgau INSEE ALSACE Dominique CALLEWAERT Mayette GREMILLET Christiane KUHN Stéphane ZINS Le territoire du Sundgau Un territoire étendu, à la population peu dense - 663 km², 102 habitants/km² : l’un des territoires de SCOT les plus étendus du Haut-Rhin mais la plus faible densité de population partagée avec le SCOT Montagne-Vignoble-Ried Une mosaïque de petites communes - Avec 112 communes, le SCOT du Sundgau totalise 30 % des communes du Haut-Rhin 9 communes sur 10 ont moins de 1 000 habitants. Hormis Altkirch, aucune n’atteint 2 500 habitants - Altkirch, chef lieu d’arrondissement de 5 600 habitants, constitue le pôle administratif et économique du territoire avec Aspach et Carspach, Altkirch forme une unité urbaine de 8 600 habitants, qui regroupe 13 % de la population et 30 % des emplois du territoire - Dannemarie (2 300 habitants), Hirsingue (2 100 habitants) et Ferrette (1 000 habitants) Chefs lieu de canton et bourgs-centres de bassin de vie Le territoire du Sundgau dans le Haut-Rhin : 30 % des communes ,19 % de la superficie, 9 % de la population, 6 % des emplois Page 2 Insee Alsace SCOT du Sundgau Février 2010 Le territoire du Sundgau Hochstatt s e b Diefmatten im Bretten Bernwiller Froeningen te Gildwiller E Ste Ammer- Une mosaïque de rnen berg Hecken zwiller Spechbach- Bellemagny le-Haut natten Falkwiller Illfurth petites communes Saint- Gueve Spechbach- Balschwiller d Secteur d’Altkirch Cosme r a le-Bas n r Traubach-le-Haut r e e ill B w - h t sc Bréchaumont Buethwiller S Heidwiller Tagolsheim m Eglingen ue Traubach-le-Bas