Women Agents in the East German State Security

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Die Thüringer CDU in Der SBZ/DDR – Blockpartei Mit Eigeninteresse

Bertram Triebel Die Thüringer CDU in der SBZ/DDR – Blockpartei mit Eigeninteresse Bertram Triebel Die Thüringer CDU in der SBZ/DDR Blockpartei mit Eigeninteresse Herausgegeben im Auftrag der Unabhängigen Historischen Kommission zur Geschichte der CDU in Thüringen und in den Bezirken Erfurt, Gera und Suhl von 1945 bis 1990 von Jörg Ganzenmüller und Hermann Wentker Herausgegeben im Auftrag der Unabhängigen Historischen Kommission zur Geschichte der CDU in Thüringen und in den Bezirken Erfurt, Gera und Suhl von 1945 bis 1990 von Jörg Ganzenmüller und Hermann Wentker Das Werk ist in allen seinen Teilen urheberrechtlich geschützt. Weiterverwertungen sind ohne Zustimmung der Konrad-Adenauer- Stiftung e.V. unzulässig. Das gilt insbesondere für Vervielfältigungen, Übersetzungen, Mikroverfilmungen und die Einspeicherung in und Verarbeitung durch elektronische Systeme. © 2019, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V., Sankt Augustin/Berlin Umschlaggestaltung: Hans Dung Satz: CMS der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. Druck: Kern GmbH, Bexbach Printed in Germany. Gedruckt mit finanzieller Unterstützung der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. ISBN: 978-3-95721-569-7 Inhaltsverzeichnis Geleitworte . 7 Vorwort . 13 Einleitung . 15 I. Gründungs- und Transformationsjahre: Die Thüringer CDU in der SBZ und frühen DDR (1945–1961) 1. Die Gründung der CDU in Thüringen . 23 2. Wandlung und Auflösung des Landesverbandes . 32 3. Im Bann der Transformation: Die CDU in den Bezirken Erfurt, Gera und Suhl bis 1961 . 46 II. Die CDU in den Bezirken Erfurt, Gera und Suhl – Eine Blockpartei im Staatssozialismus (1961–1985) 1. Die Organisation der CDU . 59 1.1. Funktion und Parteikultur der CDU . 60 1.2. Der Apparat der CDU in den Bezirken Erfurt, Gera und Suhl . 62 1.3. -

Message from the New Chairman

Subcommission on Devonian Stratigraphy Newsletter No. 21 April, 2005 MESSAGE FROM THE NEW CHAIRMAN Dear SDS Members: This new Newsletter gives me the pleasant opportunity to thank you for your confidence which should allow me to lead our Devonian Subcommission successfully through the next four years until the next International Geological Congress in Norway. Ahmed El Hassani, as Vice-Chairman, and John Marshall, as our new Secretary, will assist and help me. As it has been our habit in the past, our outgoing chairman, Pierre Bultynck, has continued his duties until the end of the calendar year, and in the name of all the Subcommission, I like to express our warmest thanks to him for all his efforts, his enthusi- asm for our tasks, his patience with the often too slow progress of research, and for the humorous, well organized and skil- ful handling of our affairs, including our annual meetings. At the same time I like to thank all our outgoing Titular Members for their partly long-time service and I express my hope that they will continue their SDS work with the same interest and energy as Corresponding Members. The new ICS rules require a rather constant change of voting members and the change from TM to CM status should not necessarily be taken as an excuse to adopt the lifestyle of a “Devonian pensioner”. I see no reason why constantly active SDS members shouldn´t become TM again, at a later stage. On the other side, the rather strong exchange of voting members should bring in some fresh ideas and some shift towards modern stratigraphical tech- niques. -

Canada As the Target of GDR Espionage Helmut Müller-Enbergs

Document généré le 2 oct. 2021 03:58 Journal of Conflict Studies Canada as the Target of GDR Espionage Helmut Müller-Enbergs Volume 29, spring 2009 Résumé de l'article German Democratic Republic (GDR) diplomatic missions included a legal URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/jcs29art04 residentur: an intelligence service base whose presence was more or less openly acknowledged. It was staffed by the Hauptverwaltung A (HVA - Main Directorate Aller au sommaire du numéro Foreign Intelligence), one of the principal divisions within the Ministerium für Staatssicherheit (Ministry for State Security). The HVA’s main task was espionage. While most of the HVA files have been destroyed, the HVA had created Éditeur(s) a special database that holds all of the information it produced between 1969 and 1989. This database allows scholars to identify which source delivered what The University of New Brunswick information and when, who received the information, and what value each piece of information had. The GDR’s Canadian embassy did not open until 1987, and ISSN due to the short term of its existence, the HVA residentur in Canada could hardly have played a significant intelligence role. And we can be almost certain that it 1198-8614 (imprimé) did not build up and manage an unofficial spy network from Canada. In fact, the 1715-5673 (numérique) HVA appears to have acquired its knowledge about Canada primarily from other sources, mainly agents within the West German foreign ministry and from other Découvrir la revue partner intelligence agencies. The GDR undoubtedly had deep insights into the domestic and foreign affairs of Canada. -

Download (515Kb)

European Community No. 26/1984 July 10, 1984 Contact: Ella Krucoff (202) 862-9540 THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT: 1984 ELECTION RESULTS :The newly elected European Parliament - the second to be chosen directly by European voters -- began its five-year term last month with an inaugural session in Strasbourg~ France. The Parliament elected Pierre Pflimlin, a French Christian Democrat, as its new president. Pflimlin, a parliamentarian since 1979, is a former Prime Minister of France and ex-mayor of Strasbourg. Be succeeds Pieter Dankert, a Dutch Socialist, who came in second in the presidential vote this time around. The new assembly quickly exercised one of its major powers -- final say over the European Community budget -- by blocking payment of a L983 budget rebate to the United Kingdom. The rebate had been approved by Community leaders as part of an overall plan to resolve the E.C.'s financial problems. The Parliament froze the rebate after the U.K. opposed a plan for covering a 1984 budget shortfall during a July Council of Ministers meeting. The issue will be discussed again in September by E.C. institutions. Garret FitzGerald, Prime Minister of Ireland, outlined for the Parliament the goals of Ireland's six-month presidency of the E.C. Council. Be urged the representatives to continue working for a more unified Europe in which "free movement of people and goods" is a reality, and he called for more "intensified common action" to fight unemployment. Be said European politicians must work to bolster the public's faith in the E.C., noting that budget problems and inter-governmental "wrangles" have overshadolted the Community's benefits. -

Palaeovolcanic and Present Magmatic Structures Along the N-S Trending Regensburg-Leipzig-Rostock Zone

Palaeovolcanic and present magmatic structures along the N-S trending Regensburg-Leipzig-Rostock zone kumulative Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktor der Naturwissenschaften doctor rerum naturalium - Dr. rer. nat. vorgelegt dem Rat der Chemisch-Geowissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena von Diplom-Geophysiker Tobias Nickschick geboren am 18.11.1985 in Wernigerode Gutachter: 1. Prof. Dr. Lothar Viereck 2. Prof. Dr. Florian Bleibinhaus Tag der Veteidigung: 18.01.2017 Vorwort Diese Abschlussarbeit entstand während meiner Anstellung und Tätigkeit als wissenschaftlicher Mit- arbeiter in der Sektion 3.2 Organische Geochemie am Helmholtz-Zentrum Potsdam - Deutsches GeoFor- schungsZentrum GFZ durch die Drittmittelfinanzierung der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft DFG in einem gemeinsamen Projekt mit der Universität Leipzig. Diese kumulative Dissertation ist in zwei in sich geschlossene Teile aufgeteilt. Der erste Teil befasst sich mit dem übergreifenden Thema der Dissertation, der Regensburg-Leipzig-Rostock-Störungszone, der zweite Teil befasst sich mit den von meinen Coautoren und mir verfassten Fachpublikationen zu ausgewählten Einzefallbeispielen innerhalb des Gesamtrahmens. Um das Gesamtlayout dieser Dissertation nicht zu stören, werden die insgesamt vier Publikationen, von denen drei bereits publiziert sind und eine eingereicht ist, in einem separaten Teil zuammengefasst präsentiert, womit der Auflage der Promotionsordnung die Originalversionen der Publikationen zu prä- sentieren, erfüllt wird. Der erste Teil wurde von mir als alleinigem Autor verfasst, die Artikel, die im zweiten Teil zusammengefasst sind, entstanden in einem Autorenkollektiv. Die Anteile des jeweiligen Kollegen an der Erstellung der Publikationen sind im Anschluss an diese Arbeit zu finden. Da die Artikel sprachlich aufgrund des Autorenkollektivs auf die 1. Person Plural zurückgreifen, wird diese auch im ersten Teil verwendet. -

Historie Jahrbuch 12.Indd

Tytus Das Fiasko eines JaskuÚowski1 (nie existierenden) Bruderbundes. Die Stasi und das Jahr 1989 in Polen 1 Der erste Teil des Titels des nachfolgenden Beitrages, der seine Formulierung den Erinnerungen des letzten DDR-Botschafters in Moskau vor der Wiedervereinigung zu verdanken hat2, spie- gelt im Wesentlichen die Enttäuschung einer ganzen Generation von Funktionären des Ministeriums für Staatssicherheit (MfS) hinsichtlich der geheimdienstlichen Beziehungen mit der Sow- jetunion wider. Sie fühlten sich 1989 vom Gründer des zweiten deutschen Staates verraten3 und zynisch ausgenutzt4. Jene Hal- tung, die verbunden war mit der ständig präsenten Hoffnung, die „alte“ Welt wiederherstellen zu können5, bezog sich auch auf die anderen osteuropäischen Länder, vor allem auf jene, welche die seit der Machtübernahme Gorbatschows im Jahr 1985 von ihm eingeleiteten Reformen begrüßten und somit eine gegensätzli- che6 Position zur dogmatischen DDR-Regierung bezogen. Den ersten Platz in dieser Gruppe von Staaten außerhalb der Sow- jetunion nahm die Volksrepublik Polen ein. Trotz der formellen Freundschaft zwischen der DDR und der Volksrepublik Polen war die gesamte Geschichte ihrer bilateralen Beziehungen von 1 Der Autor habilitiert an der Technischen Universität Chemnitz und arbeitet in der Gedenkstätte Lindenstraße in Potsdam. Er erklärt hiermit, allen rechtlichen Vorschriften nachzukommen, die den Umgang mit den Akten der ehemaligen Sicherheitsbehörden der DDR und der Volksrepublik Polen im Jahr 2019 regeln. 2 Gerd König, Fiasko eines Bruderbundes. Erinnerungen des letzten DDR-Botschafters in Moskau, Berlin 2012 (2011), S. 3. 3 Bernd Fischer, Der große Bruder. Wie die Geheimdienste der DDR und der UdSSR zusammenarbeiteten, Berlin 2012, S. 10. 4 Gabriele Gast, Kundschafterin des Friedens. 17 Jahre Topspionin der DDR beim BND, Berlin 2016, S. -

The Establishment Responds Power, Politics, and Protest Since 1945

PALGRAVE MACMILLAN TRANSNATIONAL HISTORY SERIES Akira Iriye (Harvard University) and Rana Mitter (University of Oxford) Series Editors This distinguished series seeks to: develop scholarship on the transnational connections of societies and peoples in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries; provide a forum in which work on transnational history from different periods, subjects, and regions of the world can be brought together in fruitful connection; and explore the theoretical and methodological links between transnational and other related approaches such as comparative history and world history. Editorial board: Thomas Bender University Professor of the Humanities, Professor of History, and Director of the International Center for Advanced Studies, New York University Jane Carruthers Professor of History, University of South Africa Mariano Plotkin Professor, Universidad Nacional de Tres de Febrero, Buenos Aires, and mem- ber of the National Council of Scientific and Technological Research, Argentina Pierre- Yves Saunier Researcher at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, France Ian Tyrrell Professor of History, University of New South Wales. Published by Palgrave Macmillan: THE NATION, PSYCHOLOGY AND INTERNATIONAL POLITICS, 1870–1919 By Glenda Sluga COMPETING VISIONS OF WORLD ORDER: GLOBAL MOMENTS AND MOVEMENTS, 1880s–1930s Edited by Sebastian Conrad and Dominic Sachsenmaier PAN-ASIANISM AND JAPAN’S WAR, 1931–1945 By Eri Hotta THE CHINESE IN BRITAIN, 1800–PRESENT: ECONOMY, TRANSNATIONALISM, IDENTITY By Gregor Benton and Terence -

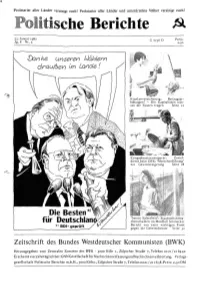

Litische Berichte Ä

Proletarier aller Länder vereinigt euch! Proletarier aller Länder und unterdrückte Völker vereinigt euch! nlitische O A © Berichte Ä 23. Januar 1987 G 7756 D Preis: Jg. 8 Nr. 2 2,50 r~ vCbn A0 Unseren IdcMern drqutöen im Lunde! Krankenversicherung: Beitragser höhungen! - Die Kapitalisten müs sen die Kosten tragen Seite 12 Kriegsdienstverweigerer: Zuviel dienst beim DRK: "Menschenführung" zur Gewinnsteigerung Seite 28 "Innere Sicherheit": Staatsschutzma chenschaften im Mordfall Schmücker Bericht von einer wichtigen Front *> BDI-geprüft gegen die Geheimdienste Seite 32 Zeitschrift des Bundes Westdeutscher Kommunisten (BWK) Herausgegeben vom Zentralen Komitee des BWK • 5000 Köln 1, Zülpicher Straße 7, Telefon 0221/216442 Erscheint vierzehntäglich bei: GNN Gesellschaft für Nachrichtenerfassung und Nachrichtenverbreitung, Verlags gesellschaft Politische Berichte m.b.H., 5000 Köln 1, Zülpicher Straße 7, Telefon 0221/211658.Preis: 2,50 DM Seite 2 Aus Verbänden und Parteien Politische Berichte 02/87 von Europas Christdemokraten warnte Aktuelles aus Politik Jüdische Zwangsarbeiter er davor, die NPD zu verketzern, denn und Wirtschaft erhalten Spottgeld auch diese Partei habe „wertvolle euro Ehemalige jüdische Zwangsarbeiter, päische Ordnungsvorstellungen“ Aus der Diskussion der Orga die in zehn Rüstungsbetrieben des G,DVZ“, 22.6.78). Die Paneuropaunion nisation: Erklärung zu den bevor Flick-Konzerns geschunden wurden, steht in enger Verbindung mit der „Ge stehenden Bundestagswahlen .... 4 sollen sich die 5 Millionen DM teilen, sellschaft fiir Menschenrechte“ (GfM), die die Feldmühle AG vor einem Jahr deren Bundesvorsitzender über deren Beschluß zu den Verhandlungen als Entschädigungssumme zu zahlen Selbstverständnis sagte: „es gelte, das zwischen Mitgliedern der Leitungen sich bereiterklärte. Ende 1986, als die ,Mittel Menschenrechte6 als ,Kampf von BWK und VSP........................ -

WEGE NACH BAUTZEN II We G E Nac H Bautz N Ii

Lebenszeugnisse – Leidenswege n ii E bautz H WEgE nac E g nacH bautzEn ii WE biographische und autobiographische Porträts Eingeleitet von Silke Klewin und Kirsten Wenzel STIFTUNG ISBN 978-3-9805527-7-6 SÄCHSISCHE GEDENKSTÄTTEN zur Erinnerung an die Opfer politischer Gewaltherrschaft 8 Heft LL8-Umschlag_042013.indd 1 06.05.13 10:00 Lebenszeugnisse – Leidenswege Heft 8 WEGE NACH BAUTZEN II Biographische und autobiographische Porträts Eingeleitet von Silke Klewin und Kirsten Wenzel Dresden 2013 Lebenszeugnisse – Leidenswege Eine Heftreihe herausgegeben von Klaus-Dieter Müller, Siegfried Reiprich und Clemens Vollnhals im Auftrag der Stiftung Sächsische Gedenkstätten zur Erinnerung an die Opfer politischer Gewaltherrschaft in Zusammenarbeit mit dem Hannah-Arendt-Institut für Totalitarismusforschung e.V. an der TU Dresden Heft 8 © Stiftung Sächsische Gedenkstätten zur Erinnerung an die Opfer politischer Gewaltherrschaft (1998) 4. korrigierte Auflage 2013 Titelfoto: Hossein Yazdi bei seiner Einlieferung nach Bautzen II, 1962 Satz: Walter Heidenreich, HAIT Dresden Umschlaggestaltung: CCP Kummer & Co. GmbH, Dresden Druck: Stoba-Druck GmbH, Lampertswalde Printed in Germany ISBN 978-3-9805527-7-6 In halts ver zeich nis Ein lei tung 7 Bio graphi sche und au to bio gra phi sche Por träts 15 Karl Wil helm Fri cke Mei ne We ge nach Baut zen II 17 Gus tav Just Der Re form kom mu nist 31 Man fred Wil ke Heinz Brandt – in Selbst zeug nis sen 45 Hoss ein Yaz di Als Ira ner in Baut zen II 61 Rein hard Borg mann Die vier Le ben der Eri ka Lo ken vitz 77 Jan-Hen rik Pe ters Adolf-Hen ning Frucht: Wis sen- schaft ler und Ama teur spi on 91 Mat thi as Bath Die Flucht hel fer Rai ner Schu bert und Hart mut Rich ter 105 Kirs ten Wen zel Char lot te Rauf ei sen: Haus frau und Mut ter 121 Sil ke Kle win/Cor ne lia Lie bold Bo do Streh low – Der ab trün ni ge Maat der Volks ma ri ne 131 An hang 145 Sil ke Kle win/Kirs ten Wen zel Ein lei tung I. -

Television and the Cold War in the German Democratic Republic

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE Revised Pages Envisioning Socialism Revised Pages Revised Pages Envisioning Socialism Television and the Cold War in the German Democratic Republic Heather L. Gumbert The University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Revised Pages Copyright © by Heather L. Gumbert 2014 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (be- yond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2017 2016 2015 2014 5 4 3 2 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978– 0- 472– 11919– 6 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978– 0- 472– 12002– 4 (e- book) Revised Pages For my parents Revised Pages Revised Pages Contents Acknowledgments ix Abbreviations xi Introduction 1 1 Cold War Signals: Television Technology in the GDR 14 2 Inventing Television Programming in the GDR 36 3 The Revolution Wasn’t Televised: Political Discipline Confronts Live Television in 1956 60 4 Mediating the Berlin Wall: Television in August 1961 81 5 Coercion and Consent in Television Broadcasting: The Consequences of August 1961 105 6 Reaching Consensus on Television 135 Conclusion 158 Notes 165 Bibliography 217 Index 231 Revised Pages Revised Pages Acknowledgments This work is the product of more years than I would like to admit. -

Approach/Avoidance: Communists and Women in East Germany, 1945-9 Author(S): Donna Harsch Source: Social History, Vol

Approach/Avoidance: Communists and Women in East Germany, 1945-9 Author(s): Donna Harsch Source: Social History, Vol. 25, No. 2 (May, 2000), pp. 156-182 Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4286643 Accessed: 24-04-2018 15:00 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Taylor & Francis, Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Social History This content downloaded from 35.176.47.6 on Tue, 24 Apr 2018 15:00:46 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Social History Vol. 25 No. 2 May 2000 0* Donna Harsch Approach/avoidance: Communists and women in East Germany, 1945-9 In July 1945, a German Communist scolded fellow members of the KPD for how they talked to women in the Soviet zone of occupation. According to Irene Girtner (aka Elli Schmidt), her comrades opened lectures to female audiences with the question: 'Is it not a fact that Hitler came to power only because a high proportion of women succumbed to the poison of Nazi propaganda?'l A year later, Schmidt rued, Communists continued to make the 'error' of expounding on the guilt women bore for the fascist seizure of power.2 As late as May 1947, another woman in the party felt the need to point out that, infact, women had voted at a lower rate for Hitler in I928, only catching up to the male vote in I93I-2.3 For her part, Elli Schmidt did not question the accuracy of the charge but its political acumen. -

Tafeln (Page 1)

"Forgotten" History BERUFSVERBOTE Political Persecution in the Federal Republic of Germany 1. DEFINITION Berufsverbot? What is That? At the end of the 1960s, politicians, lawyers, police and secret Aim of Berufsverbot: Intimidation by Threat of Subsistence Deprivation services considered how to contain mass protests at universities and Political repression and political persecu- work places. The forms of repression practiced so far – surveillance, tion has happened and is still happening police raids, political trials and imprisonment – didn't seem to be in many areas of society. sufficient anymore. In particular, the state authorities were What was so special about the "Radikalen - concerned that a new generation with left-wing leanings could erlass"? Its aim was to abolish the mate- rial existence of the affected people in the permeate the governmental structures and change them from workplace. Those affected either could the inside. A working group commissioned in 1971 discussed not complete their education or could not possibilities to keep left-wing critics out of the civil service. practise their professions, because these The measures to be taken were meant to be intimidating and were monopolised by the state. Therefore, Berufsverbote have lifelong existential deterrent. On the basis of this, the Prime Ministers of the Länder consequences for those affected. under the chair of Chancellor Willy Brandt on January 28, 1972 passed what became known as the "Anti-radicals Decree*" (Radikalenerlass). The "Radikalenerlass" Violated Essential Basic and Human Rights: Hurry up, gentlemen, 1. The principle of equality and here is another radical who wants the non-dis crimination rule to get into the civil service.