The Karelian Female Name System (FUF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No Solutions for Water-Short Area

Property of the Watertown Historical Society watertownhistoricalsociety.org Timely Coverage Of News in The Fastest Growing Community in Litehfield County Vol. 40 No. 32 SUBSCRIPTION PRICE $12.00 PER, YEAR Car. Rt. P.S. PRICE 30 CENTS August 8, 1985 v Developers Raising Dust Along Main ThoroughfareNo Solutions For Site plan renderings and specifications on, paper that went to town zoning officials last fall are bearing, fruition 'this summer through, a. host of noticeable building projects underway along Main Street. All of it has left Stanley Masayda, zoning enforcement officer, with Water-Short Area; the observation that "things sure are busy!" The largest excavation project occurring these days is next to Pizza Hut, where a large sloped lot almost has been brought down to street level. The project of Anthony Cocchiola and Raymond Brennan even- tually will see a two-story office building on the site. Wells Investigated Plans were submitted to and approved by the Planning and Zoning Residents of the Grandview and Nova Scotia Hill Pair Circuit Avenues area of town, came to Monday night's Town Council meeting hoping to find sonic solu- Lodge Park Complaints tions for their ongoing dilemma of living, without adequate .water. The vice chairman, of the Town, woman Barbara HyincI,. authoriz- ed Town Manager Robert Mid- The only cone I us ion reached was Council Monday night asked the at this moment there is none, and town manager to nave a full report daugh to look into the charges made by Joseph Zu rait is, 555 Nova officials still arc trying to come up prepared for a future Council with a plan. -

Laura Stark Peasants, Pilgrims, and Sacred Promises Ritual and the Supernatural in Orthodox Karelian Folk Religion

laura stark Peasants, Pilgrims, and Sacred Promises Ritual and the Supernatural in Orthodox Karelian Folk Religion Studia Fennica Folkloristica The Finnish Literature Society (SKS) was founded in 1831 and has, from the very beginning, engaged in publishing operations. It nowadays publishes literature in the fields of ethnology and folkloristics, linguistics, literary research and cultural history. The first volume of the Studia Fennica series appeared in 1933. Since 1992, the series has been divided into three thematic subseries: Ethnologica, Folkloristica and Linguistica. Two additional subseries were formed in 2002, Historica and Litteraria. The subseries Anthropologica was formed in 2007. In addition to its publishing activities, the Finnish Literature Society maintains research activities and infrastructures, an archive containing folklore and literary collections, a research library and promotes Finnish literature abroad. Studia fennica editorial board Anna-Leena Siikala Rauno Endén Teppo Korhonen Pentti Leino Auli Viikari Kristiina Näyhö Editorial Office SKS P.O. Box 259 FI-00171 Helsinki www.finlit.fi Laura Stark Peasants, Pilgrims, and Sacred Promises Ritual and the Supernatural in Orthodox Karelian Folk Religion Finnish Literature Society • Helsinki 3 Studia Fennica Folkloristica 11 The publication has undergone a peer review. The open access publication of this volume has received part funding via Helsinki University Library. © 2002 Laura Stark and SKS License CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International. A digital edition of a printed book first published in 2002 by the Finnish Literature Society. Cover Design: Timo Numminen EPUB: eLibris Media Oy ISBN 978-951-746-366-9 (Print) ISBN 978-951-746-578-6 (PDF) ISBN 978-952-222-766-9 (EPUB) ISSN 0085-6835 (Studia Fennica) ISSN 1235-1946 (Studia Fennica Folkloristica) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21435/sff.11 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International License. -

Kalevalan Maat

KALEVALAN MAAT Pelikorttien kuvitusprojekti - Opinnäytetyö MINNA HUSSO KVA9SG / Graafinen Viestintä Kuopion Muotoiluakatemia Kalevalan maat Pelikorttien kuvitusprojekti Minna Husso Opinnäytetyö ___. ___. ______ ________________________________ Ammattikorkeakoulututkinto SAVONIA-AMMATTIKORKEAKOULU OPINNÄYTETYÖ Tiivistelmä Koulutusala Kulttuuriala, Kuopio Koulutusohjelma Viestinnän koulutusohjelma Työn tekijä Minna Husso Työn nimi Kalevalan maat - pelikorttien kuvitusprojekti Päiväys 22.4.2012 Sivumäärä/Liitteet 35/4 Ohjaaja(t) Jouko Kivimäki, Marja-Sisko Kataikko Toimeksiantaja/Yhteistyökumppani(t) Henkilökohtainen projekti Tiivistelmä Tekijän lähtökohtana oli suunnitella kuvituksia pelikorttipakkaan. Kuvitukset pohjautuivat Kalevalan taruston hahmoihin ja olivat ilmaisullisesti toteu- tettu. Tekijä perehtyi Kalevalaan ja pelikorttien historiaan, jonka kautta hän muodosti omat näkemyksensä toteutettavista kuvituksista. Taustatietoa hankittiin tutkimalla pelikorttien historiaa, analysoimalla muutamia korttipelejä ja tutkimalla tekijän lempitaiteilijoita ja heidän töitään. Näiden taustatietojen lisäksi tutkittiin Kalevala eeposta ja sen taruston henkilöitä, jotka analysoitiin ja jaoteltiin pelikorttien kuvakortteihin. Pelikorttien kuvituksiksi ideoitiin tekijän näköinen kokonaisuus, jonka tarkoitus oli olla moderni ja näyttävä. Kuvitusten tyyli henkii tekijän omia intui- tiivisia ajatuksia ja mieltymyksiä Kalevalan hahmoista. Tekijä toteutti 52 kortin pelipakan, jossa oli 16 kuvallista korttia, 36 numerokorttia ja kaksi kuvallista jokerikorttia. -

Editors' Introduction Douglas A

Editors' Introduction Douglas A. Anderson Michael D. C. Drout Verlyn Flieger Tolkien Studies, Volume 7, 2010 Published by West Virginia University Press Editors’ Introduction This is the seventh issue of Tolkien Studies, the first refereed journal solely devoted to the scholarly study of the works of J.R.R. Tolkien. As editors, our goal is to publish excellent scholarship on Tolkien as well as to gather useful research information, reviews, notes, documents, and bibliographical material. In this issue we are especially pleased to publish Tolkien’s early fiction “The Story of Kullervo” and the two existing drafts of his talk on the Kalevala, transcribed and edited with notes and commentary by Verlyn Flieger. With this exception, all articles have been subject to anonymous, ex- ternal review as well as receiving a positive judgment by the Editors. In the cases of articles by individuals associated with the journal in any way, each article had to receive at least two positive evaluations from two different outside reviewers. Reviewer comments were anonymously conveyed to the authors of the articles. The Editors agreed to be bound by the recommendations of the outside referees. The Editors also wish to call attention to the Cumulative Index to vol- umes one through five of Tolkien Studies, compiled by Jason Rea, Michael D.C. Drout, Tara L. McGoldrick, and Lauren Provost, with Maryellen Groot and Julia Rende. The Cumulative Index is currently available only through the online subscription database Project Muse. Douglas A. Anderson Michael D. C. Drout Verlyn Flieger v Abbreviations B&C Beowulf and the Critics. -

Teaching the Short Story: a Guide to Using Stories from Around the World. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 397 453 CS 215 435 AUTHOR Neumann, Bonnie H., Ed.; McDonnell, Helen M., Ed. TITLE Teaching the Short Story: A Guide to Using Stories from around the World. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-1947-6 PUB DATE 96 NOTE 311p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 19476: $15.95 members, $21.95 nonmembers). PUB 'TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) Collected Works General (020) Books (010) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Authors; Higher Education; High Schools; *Literary Criticism; Literary Devices; *Literature Appreciation; Multicultural Education; *Short Stories; *World Literature IDENTIFIERS *Comparative Literature; *Literature in Translation; Response to Literature ABSTRACT An innovative and practical resource for teachers looking to move beyond English and American works, this book explores 175 highly teachable short stories from nearly 50 countries, highlighting the work of recognized authors from practically every continent, authors such as Chinua Achebe, Anita Desai, Nadine Gordimer, Milan Kundera, Isak Dinesen, Octavio Paz, Jorge Amado, and Yukio Mishima. The stories in the book were selected and annotated by experienced teachers, and include information about the author, a synopsis of the story, and comparisons to frequently anthologized stories and readily available literary and artistic works. Also provided are six practical indexes, including those'that help teachers select short stories by title, country of origin, English-languag- source, comparison by themes, or comparison by literary devices. The final index, the cross-reference index, summarizes all the comparative material cited within the book,with the titles of annotated books appearing in capital letters. -

Magic Songs of the West Finns, Volume 1 by John Abercromby

THE PRE- AND PROTO-HISTORIC FINNS BOTH EASTERN AND WESTERN WITH THE MAGIC SONGS OF THE WEST FINNS BY THE HONOURABLE JOHN ABERCROMBY IN TWO VOLUMES VOL. I. 1898 Magic Songs of the West Finns, Volume 1 by John Abercromby. This edition was created and published by Global Grey ©GlobalGrey 2018 globalgreyebooks.com CONTENTS Preface The Value Of Additional Letters Of The Alphabet Full Titles Of Books Consulted And Referred To Illustrations Chapter 1. Geographical Position And Craniology Of The Finns Chapter 2. The Neolithic Age In Finland Chapter 3. Historical Notices Of Classical Authors Chapter 4. The Prehistoric Civilisation Of The Finns Chapter 5. The Third Or Iranian Period Chapter 6. Beliefs Of The West Finns As Exhibited In The Magic Songs 1 PREFACE In this country the term Finn is generally restricted to the natives of Finland, with perhaps those of Esthonia thrown in. But besides these Western Finns there are other small nationalities in Central and Northern Russia, such as the Erza and Mokša Mordvins, the Čeremis, Votiaks, Permians, and Zịrians, to whom the term is very properly applied, though with the qualifying adjective—Eastern. Except by Folklorists, little attention is paid in Great Britain to these peoples, and much that is written of them abroad finds no response here, the 'silver streak' acting, it would seem, as a non-conductor to such unsensational and feeble vibrations. Although the languages of the Eastern and Western Finns differ as much perhaps among themselves as the various members of the Aryan group, the craniological and physical differences between any two Finnish groups is very much less than between the Latin and the Teutonic groups, for instance. -

Mead Variants

Mead Variants (From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia) Tr6jniak - A Polish mead, made using two units of water for each unit of honey Acerglyn - A mead made with honey and maple syrup. Balche - A native Mexican version of mead. Black mead - A name sometimes given to the blend of honey and black currants. Bochet - A mead where the honey is caramelized or burned separately before adding the water. Yields toffee, chocolate, and marshmallow flavors. Braggot - Also called bracket or brackett. Originally brewed with honey and hops, later with honey and malt - with or without hops added. Welsh origin (bragawd). Capsicumel - A mead flavored with chili peppers. Chouchenn - A kind of mead made in Brittany. Cyser - A blend of honey and apple juice fermented together; see also cider. Czw5rniak (TSG) - A Polish mead, made using three units of water for each unit of honey Dandaghare - A mead from Nepal, combines honey with Himalayan herbs and spices. lt has been brewed since 1972 in the city of Pokhara. Dw6jniak(Tsc) - A Polish mead, made using equal amounts of water and honey Great mead - Any mead that is intended to be aged several years. The designation is meant to distinguish this type of mead from "short mead" (see below). Gverc or Medovina - Croatian mead prepared in Samobor and many other places. The word "gverc" or "gvirc' is from the German "Gewiirze" and refers to various spices added to mead. Hydromet - Literally "water-honey" in Greek. lt is also the French name for mead. (Compare with the Catalan hidromel, Galician aiguamel, Portuguese hidromel, ltalian idromele, and Spanish hidromiel and aguamiel). -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Social Reality and Mythic Worlds Reflections on Folk Belief and the Supernatural in James Macpherson’s Ossian and Elias Lönnrot’s Kalevala Ersev Ersoy PhD THE UNIVERSITY of EDINBURGH OILTHIGH DHÙN ÈIDEANN 2012 Abstract This thesis investigates the representation of social reality that can be reflected by folk belief and the supernatural within mythic worlds created in epic poetry. Although the society, itself, can be regarded as the creator of its own myth, it may still be subjected to the impact of the synthesized mythic world, and this study seeks to address the roles of the society in the shaping of such mythic worlds. The research is inspired by an innovative approach, using James Macpherson’s Ossian (1760-63) and Elias Lönnrot’s Kalevala (1835-49) as epic models that benefit from mythical traditions. -

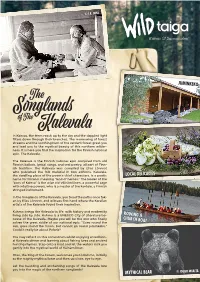

The Songlands of the Kalevala

© I.K. INHA JUMINKEKO In Kainuu, the trees reach up to the sky and the dappled light filters down through their branches. The murmuring of forest streams and the soothing hum of the verdant forest greet you and lead you to the mystical beauty of this northern wilder- ness. It is here you find the inspiration for the Finnish national epic, The Kalevala. The Kalevala is the Finnish national epic compiled from old Finnish ballads, lyrical songs, and oral poetry, all part of Finn- ish tradition. The Kalevala was compiled by Elias Lönnrot who published the folk material in two editions. Kalevala, the dwelling place of the poem’s chief characters, is a poetic LOCAL DELICACIES name for Finland, meaning “land of heroes.” The leader of the “sons of Kaleva” is the wise old Väinämöinen, a powerful sage with intuitive powers, who is a master of the kantele, a Finnish stringed instrument. In the Songlands of the Kalevala, you tread the paths once tak- en by Elias Lönnrot, and witness first hand where the Karelian artists of the Kalevala found their inspiration. Kuhmo brings the Kalevala to life, with history and modernity living side by side. Kuhmo is a UNESCO City of Literature be- ROWING A cause of the Kalevala. Maybe you will be the one who finally CHURCH BOAT solves the great riddle of our national epic: “Goes round the sun, goes round the moon, but cannot go round juminkeko.” Could it really be about Polaris? You may reflect on this conundrum whilst enjoying a tradition- al Kalevala dinner and learning about fishing lures and ancient hunting rhymes. -

Official Directory of the European Union

ISSN 1831-6271 Regularly updated electronic version FY-WW-12-001-EN-C in 23 languages whoiswho.europa.eu EUROPEAN UNION EUROPEAN UNION Online services offered by the Publications Office eur-lex.europa.eu • EU law bookshop.europa.eu • EU publications OFFICIAL DIRECTORY ted.europa.eu • Public procurement 2012 cordis.europa.eu • Research and development EN OF THE EUROPEAN UNION BELGIQUE/BELGIË • БЪЛГАРИЯ • ČESKÁ REPUBLIKA • DANMARK • DEUTSCHLAND • EESTI • ΕΛΛΑΔΑ • ESPAÑA • FRANCE • ÉIRE/IRELAND • ITALIA • ΚΥΠΡΟΣ/KIBRIS • LATVIJA • LIETUVA • LUXEMBOURG • MAGYARORSZÁG • MALTA • NEDERLAND • ÖSTERREICH • POLSKA • PORTUGAL • ROMÂNIA • SLOVENIJA • SLOVENSKO • SUOMI/FINLAND • SVERIGE • UNITED KINGDOM • BELGIQUE/BELGIË • БЪЛГАРИЯ • ČESKÁ REPUBLIKA • DANMARK • DEUTSCHLAND • EESTI • ΕΛΛΑ∆Α • ESPAÑA • FRANCE • ÉIRE/IRELAND • ITALIA • ΚΥΠΡΟΣ/KIBRIS • LATVIJA • LIETUVA • LUXEMBOURG • MAGYARORSZÁG • MALTA • NEDERLAND • ÖSTERREICH • POLSKA • PORTUGAL • ROMÂNIA • SLOVENIJA • SLOVENSKO • SUOMI/FINLAND • SVERIGE • UNITED KINGDOM • BELGIQUE/BELGIË • БЪЛГАРИЯ • ČESKÁ REPUBLIKA • DANMARK • DEUTSCHLAND • EESTI • ΕΛΛΑΔΑ • ESPAÑA • FRANCE • ÉIRE/IRELAND • ITALIA • ΚΥΠΡΟΣ/KIBRIS • LATVIJA • LIETUVA • LUXEMBOURG • MAGYARORSZÁG • MALTA • NEDERLAND • ÖSTERREICH • POLSKA • PORTUGAL • ROMÂNIA • SLOVENIJA • SLOVENSKO • SUOMI/FINLAND • SVERIGE • UNITED KINGDOM • BELGIQUE/BELGIË • БЪЛГАРИЯ • ČESKÁ REPUBLIKA • DANMARK • DEUTSCHLAND • EESTI • ΕΛΛΑΔΑ • ESPAÑA • FRANCE • ÉIRE/IRELAND • ITALIA • ΚΥΠΡΟΣ/KIBRIS • LATVIJA • LIETUVA • LUXEMBOURG • MAGYARORSZÁG • MALTA • NEDERLAND -

PANTHEON Finnois

PANTHEON OUGRO-FINNOIS AARNIVALKEA: flamme éternelle qui marque l'emplacement d'un trésor enterré. AHTI (ou Ahto): dieu des eaux, des lacs, des rivières et des mers et de la pêche. AJATTARA (ou Ajatar): esprit maléfique des forêts. AKKA: (vielle femme) déesse-mère de la fécondité féminine, de la sexualité et des moissons, consort de Ukko ÄKRÄS: dieu de la Fertilité et de la Végétation. ANTERO VIPUNEN: géant défunt, protecteur de la Connaissance et de la Magie. ATHOLA : château d’Athi. HALTIA: esprit, gnome, gardien d’une personne ou d’un lieu. Maan-haltiat (esprits terrestres), Veden-haltiat (esprits de l'eau), et Ilman-haltiat (esprits de l'air) HIISI : démon, gobelin et homme de main de Lempo. IHTIRIEKO: protecteur des enfants illégitimes privés de vie. IKU-TURSO: monstre marin maléfique sans doute identique à Tursas. ILMA : dieu de l'air, père d’Ilmatar. ILMARINEN : grand forgeron qui créa le ciel et le Sampo. ILMATAR: esprit féminin de l'air, créatrice du Monde; Mère de Väinämöinen dans le Kalevala. JOUKAHAINEN : garçon qui défia Vâinâmôinen à un concours de chant. JUMALA : nom générique des divinités majeures ; dieu. KALEVANPOIKA : géant qui abattit les forêts et faucha les immenses prairies. En Estonie : Kalevipoeg. KAVE: ancien dieu du ciel puis divinité du cycle lunaire. Père de Väinämöinen. KALEVALA : grande épopée composée par Elias Lönnrot au milieu du XIXe siècle. KALMA : déesse de la Mort et de Décomposition. KANTELE : magie faite à partir de la gueule d’un brochet par Väinämöinen. KIED-KIE-JUBMEL: dieu des troupeaux de rennes KILLIKKI : épouse de Lemminkainen qui aimait faire la fête KIPU-TYTTÖ : déesse de la Mort et de la Maladie, sœur de Kivutar, Vammatar, et Loviatar. -

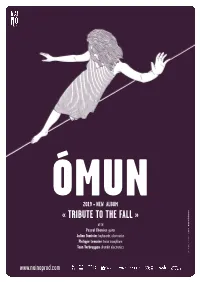

OMUN – 2Nd Record – Tribute to the Fall

ÓMUN 2019 • NEW ALBUM « TRIBUTE TO THE FALL » WITH www.atelierhurf.net Pascal Charrier: guitar MMXVIII Julien Tamisier: keyboards, electronics Yannis Frier Yannis Philippe Lemoine: tenor saxophone > DESIGN Teun Verbruggen: drumkit, electronics GRAPHIC www.nainoprod.com ÓMUN 1 ÓMUN brings together four musicians from the European contemporary jazz and improvised music scenes: Pascal Charrier (guitar), Julien Tamisier (keyboards, electronics), Philippe Lemoine (tenor saxophone) and Teun Verbruggen (drumkit, electronics). The quartet’s sound is a combination of timbres and resonances. Every kind of approach is taken in a mixture of acoustic, electric, uncommon instrumental sounds as well as electronic and electroacoustic treatment of various sound sources. Dramatic generation of material and soundscapes disrupt bearings and invent a instantaneous poetry through processing, deconstruction and distortion. The listener navigates through a sea of reminiscences, guided by fragments of melodies like the residues of a collective memory. With this new repertory, the music places sound matter at the centre of the drama, questioning notions of permanence (emotions, bodies, ideas) and time (perpetual movement, spirals, abysses). The traditional stage/audience layout is also questioned with the creation of a circular common ground which gives both performers and audience the possibility to move around, thus changing their visual and auditive perception. This project is also pushed forward in the quintet version of the show called ÓMUN-IMAGE, in which