September 1932, Volume 8, No. 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

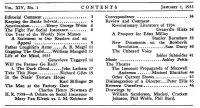

Vol. XIV, No. 1 CONTENTS JANUARY 1, 1935 Editorial

VoL. XIV, No. 1 CONTENTS JANUARY 1, 1935 Editorial Comment • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • .. ..• 3 Correspondence • . • • . • • . • • . • • • • • • . • . • • 34 Keeping the Banks Solvent.............. 6 Review and Comment Americanism .•.••••. Henry George Weiss 6 Revolutionary Literature of 1934 The Fight For Social Insurance. • • • . • • • • 8 Granville Hicks 36 One Year of the Weekly New Masses A Prospect for Edna Millay A Statement to Our Readers and an · Stanley Burnshaw 39 Appeal • • ••••• ••••••. .• • • • . • • ••• 9 New Documents on the Bolshevik Father Coughlin's Army .••.. A. B. Magi! 11 Revolution ...•..••.•.•• Sam Darcy 40 Gagging The Guild •••• William Mangold 15 The Unheard Voice Life of the Mind, 1935 Isidor Schneider 41 Genevieve Taggard 16 Music .................... Ashley Pettis Will the Farmer Go Red? The Theatre 5. The Dark Cloud ...... John Latham 17 The Innocent Propaganda of Maxwell Take This Hope .......•... Richard Giles 19 Anderson ••....• Michael Blankfort 44 In the Nazis' Torture House Other Current Shows .•.••••.••••..•• 45 Karl Billinger 20 Disintegration of a Director ••. Peter Ellis 45 The Man at the Factory Gate Between Ourselves • • • • • • • • . • • • . • • • • . • • . 46 Charles Henry Newman 27 Drawings by H. R. 7598-A Debate on Social Insurance William Sanderson, Mackey, Crockett Mary Van Kleeck ,ys. I. M. Rubinow 28 Johnson, Phil Wolfe, Phil Bard. VoL. XIV, No. 2 CONTENTS JANUARY 8, 1935 Editorial Comment . • . • . • • . 3 Arming the Masses .••.••••. Ben Field 25 Betrayal by the N.A.A.C.P. •. • . • 6 American Decadence Mapped Terror in "Liberal" Wisconsin........... 8 .Samuel Levenson 25 The Truth About the Crawford Case Fire on the Andes •••... Frank Gordon 26 Martha Gruening 9 Brief Review ••••••••••••••• , • • • . • • 27 Moscow Street. ....... Charles B. Strauss 15 Book Notes •••••••••••••••.••.•••••• 27 The Auto Workers Face 1935 Art A. -

JOHN REED and the RUSSIAN REVOLUTION Also by Eric Homberger

JOHN REED AND THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION Also by Eric Homberger JOHN REED * AMERICAN WRITERS AND RADICAL POLITICS, 190~1939 JOHN LE CARRE THE ART OF THE REAL: POETRY IN ENGLAND AND AMERICA SINCE 1939 EZRA POUND: THE CRITICAL HERITAGE (editor) * THE TROUBLED FACE OF BIOGRAPHY (editor with John Charmley) THE CAMBRIDGE MIND (editor with Simon Schama and William Janeway) * THE SECOND WORLD WAR IN FICTION (editor with Holger Klein and John Flower) * Also published by Macmillan John Reed and the Russian Revolution Uncollected Articles, Letters and Speeches on Russia, 1917-1920 Edited by ERIC HaMBERGER Visiting Professor of American Studies University of New Hampshire with JOHN BIGGART Lecturer in Russian History University of East Anglia M MACMILLAN ISBN 978-1-349-21838-7 ISBN 978-1-349-21836-3 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-21836-3 Editorial matter and selection © Eric Hornberger and John Biggart 1992 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1992 978-0-333-53346-8 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 33-4 Alfred Place, London WClE 7DP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. First published 1992 Published by MACMILLAN ACADEMIC AND PROFESSIONAL LTD Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 2XS and London Companies and representatives throughout the world British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Reed, John, 1887-1920 John Reed and the Russian revolution: uncollected articles, letters and speeches on Russia, 1917-1920. -

The Impact of Anti-Communism on the Development of Marxist Historical Analysis Within the Historical Profession of the United States, 1940-1960

BUILDING THE ABSENT ARGUMENT: THE IMPACT OF ANTI-COMMUNISM ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF MARXIST HISTORICAL ANALYSIS WITHIN THE HISTORICAL PROFESSION OF THE UNITED STATES, 1940-1960 Gary Cirelli A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2010 Committee: Dr. Douglas J. Forsyth, Advisor Dr. Don K. Rowney Dr. Timothy Messer-Kruse © 2010 Gary Cirelli All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Douglas Forsyth, Advisor This study poses the question as to why Marxism never developed in the United States as a method of historical analysis until the mid-1960s. In this regard, the only publication attempting to fully address this question was Ian Tyrrell’s book The Absent Marx: Class Analysis and Liberal History in Twentieth-Century America, in which he argued that the lack of Marxist historical analysis is only understood after one examines the internal development of the profession. This internalist argument is incomplete, however, because it downplays the important impact external factors could have had on the development of Marxism within the profession. Keeping this in mind, the purpose of this study is to construct a new argument that takes into account both the internal and external pressures faced by historians practicing Marxism preceding the 1960s. With Tyrrell as a launching pad, it first uses extensive secondary source material in order to construct a framework that takes into account the political and social climate prior to 1960. Highlighting the fact that Marxism was synonymous with Communism in the minds of many, it then examines the ways in which the government tried to suppress Communism and the impact this had on the academy. -

Out of Left Field: William Saroyan's Thirties Fiction As a Reflection of the Great Depression

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1992 Out of Left Field: William Saroyan's Thirties Fiction as a Reflection of the Great Depression Hildy Michelle Coleman College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Coleman, Hildy Michelle, "Out of Left Field: William Saroyan's Thirties Fiction as a Reflection of the Great Depression" (1992). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625708. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-jmzn-hy82 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OUT OF LEFT FIELD: WILLIAM SAROYAN'S THIRTIES FICTION AS A REFLECTION OF THE GREAT DEPRESSION A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of American Studies The College of William and Mary In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Hildy Coleman 1992 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Approved, December 1992 Prof. Scott Donaldson Prof. RO/bert Gross Prof. Richard Lowry TABLE OF CONTENTS Page APPROVAL SHEET . ..................................... ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................... iv ABSTRACT . v THESIS ................................. 2 NOTES ................................................ 49 BIBLIOGRAPHY .......................................... 51 VITA ................... 54 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am deeply grateful to Dr. Scott Donaldson for his sound advice on matters of form and substance during the writing of this Saroyan paper. -

Communists and the Classroom: Radicals in U.S. Education, 1930-1960 Jonathan Hunt University of San Francisco, [email protected]

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Rhetoric and Language Faculty Publications and Rhetoric and Language Research 2015 Communists and the Classroom: Radicals in U.S. Education, 1930-1960 Jonathan Hunt University of San Francisco, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.usfca.edu/rl_fac Part of the Education Commons, English Language and Literature Commons, and the Political History Commons Recommended Citation Hunt, J. (2015). Communists and the Classroom: Radicals in U.S. Education, 1930-1960. Composition Studies, 43(2), 22-42. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Rhetoric and Language at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Rhetoric and Language Faculty Publications and Research by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Articles Communists and the Classroom: Radicals in U.S. Education, 1930–1960 Jonathan Hunt Concern about Communists in education was a central preoccupation in the U.S. through the middle decades of the twentieth century. Focusing on post-secondary and adult education and on fields related to composition and rhetoric, this essay offers an overview of the surprisingly diverse con- texts in which Communist educators worked. Some who taught in Com- munist-sponsored “separatist” institutions pioneered the kinds of radical pedagogical theories now most often attributed to Paulo Freire. Communist educators who taught in “mainstream” institutions, however, less often saw their pedagogy as a mode of political action; their activism was deployed mainly in civic life rather than the classroom. -

Appendix I: a Letter on John Reed's 'The Colorado War'

Appendix I: A Letter on John Reed's 'The Colorado War' Boulder, Colorado. December 5 1915 My dear Mr Sinclair:- I have your letter of Ist inst. I do not think the reporter always got me quite right, or as fully as he might have got me. I did, however, think at the time I testified that Reed's paper in The Metropolitan contained some exaggerations. I did not intend to say that he intentionally told any untruths, and doubtless he had investigated carefully and could produce witnesses to substantiate what he said. Some things are matters of opinion. Some others are almost incapable ofproof. The greater part of Reed's paper is true. But for example, p. 14 1st column July (1914) Metropolitan: 'And orders were that the Ludlow colony must be wiped out. It stood in the way ofMr. Rockefeller's profits.' I believe that a few brutes like Linderfelt probably did intend to wipe this colony out, but that orders were given to this effect by any responsible person either civil or military - is incapable of proof. So the statement that 'only seventeen of them [strikers] had guns', I believe from what Mrs Hollearn [post-mistress] tells me is not quite correct. On p. 16 Reed says the strikers 'eagerly turned over their guns to be delivered to the militia' - Now it is pretty clear from what happened later that many guns were retained: on Dec. 31 st I was at Ludlow when some 50 or so rifles - some new, some old - were found under the tents and there were more - not found. -

The Aesthetic Diversity of American Proletarian Fiction

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2001 The aesthetic diversity of American proletarian fiction Walter Edwin Squire University of Tennessee Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Recommended Citation Squire, Walter Edwin, "The aesthetic diversity of American proletarian fiction. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2001. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/6387 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Walter Edwin Squire entitled "The aesthetic diversity of American proletarian fiction." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. Mary E. Papke, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Walter Squire entitled "The Aesthetic Diversity of American Proletarian Fiction." I have examined the final copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. -

The Theory and Practice of the American Proletarian Novel, Based Upon Four Selected Works

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1979 Toward a Workers' America: the Theory and Practice of the American Proletarian Novel, Based Upon Four Selected Works. Joel Dudley Wingard Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Wingard, Joel Dudley, "Toward a Workers' America: the Theory and Practice of the American Proletarian Novel, Based Upon Four Selected Works." (1979). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 3425. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/3425 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Pagefs)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round Mack mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. -

Joseph Freeman Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf209n98ch No online items Register of the Joseph Freeman papers Finding aid prepared by Rebecca J. Mead Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 1998 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Register of the Joseph Freeman 80159 1 papers Title: Joseph Freeman papers Date (inclusive): 1904-1966 Collection Number: 80159 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 187 manuscript boxes, 3 card file boxes, 1 oversize box, 1 slide box, 1 album box, 40 envelopes, 2 sound discs(81.4 Linear Feet) Abstract: Writings, correspondence, printed matter, notes, and photographs relating to the relation between communism and art and literature, and to communism in the United States, Mexico, and the Soviet Union. Creator: Freeman, Joseph, 1897-1965 Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access Box 191 closed; use copies available in envelopes F, G, and I. The remainder of the collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives in 1980. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Joseph Freeman papers, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Library & Archives. 1897 Born, Piratin, Poltawa, Ukraine -

Granville Hicks: an Annotated Bibliography

THE EMPORIA STATE RESEARCH STUDIES !l2S GRADUATE PUBLICATION OF THE KANSAS STATE TEACHERS COLLEGE, EMPORIA 4 Granville Hicks: An Annotated Bibliography February, 1927 to June, 1967 with a Supplement to June, 1968 Robert J. Bicker 7he€mpori& stateRed emch stub KANSAS STATE TEACHERS COLLEGE EMPORIA, KANSAS 66801 Granville Hicks An Annotated Bibliography February, 1927 to June, 1967 with a Supplement to June, 1968 by Rolbert J. Bicker VOLUME XVII DECEMBER, 1968 NUMBER 2 ! 1 THE EMPORIA STATE RESEARCH STTJDIES is published in September, I December, March, and June of each year by the Graduate Division of the -1 ak /-- Kansas State Teachers College, 1200 Commercial St., Emporia, Kansas, 66801. -*i f Entered as second-class matter September 16, 1952, at the post office at Em- 1 poria, Kansas, under the act of August 24, 1912. Postage paid at Emporia, 4?- Kansas. Printed in The Ernpol-ia State Research Studies with the permission of the author Copyright @ 1969 by Robert J. Bicker Printed in the U.S.A. "Statement required by the Act of October, 1962; Section 4369, Title 39, United States Code, showing Ownership, Management and Circulation.'' The Emporla, State Research Studies is published in September, December, March and June of each year. Editorial Office and Publication. Office at' 1200 Commercial Street, Empria, Kansas. (66801). The Research Stuades is edited and published by the Kansas State Teachers College, Emporia, Kansas. A complete list of all publications of The Emporia State - Research Studies is published in the fourth number of each volume. KANSAS STATE TEACHERS COLLEGE EMPORIA, KANSAS JOHN E. VISSER President of the Colkge THE GRADUATE DIVISION LAURENCEC. -

Small Town 000 Hicks FM R.Ts 9/30/04 1:38 AM Page Ii

000_Hicks_FM_R.ts 9/30/04 1:38 AM Page i small town 000_Hicks_FM_R.ts 9/30/04 1:38 AM Page ii Portrait-photograph of Granville Hicks taken about 1943 by Lotte Jacobi. (Courtesy Craib family) 000_Hicks_FM_R.ts 9/30/04 1:38 AM Page iii Granville Hicks SMALL TOWN fordham university press new york 2004 000_Hicks_FM_R.ts 9/30/04 1:38 AM Page iv Copyright © 2004 Fordham University Press “Preface to the Fordham University Press Edition,” copyright © 2004 Ron Powers “Granville Hicks: Champion of the Small Town” and “A Granville Hicks Bibliography,” copyright © 2004 Warren F. Broderick All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means— electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hicks, Granville, 1901– Small town / Granville Hicks.—1st Fordham University Press ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. Originally published : New York : Macmillan, 1946. With new pref. and biographical essay. ISBN 0-8232-2357-4 (hardcover) 1. City and town life. 2. Intellectuals. 3. Cities and towns—United States. I. Title. HT153.H53 2004 307.76—dc22 2004014754 Printed in the United States of America 08 07 06 05 04 5 4 3 2 1 First Macmillan Company edition, 1946 First Fordham University Press edition, 2004 000_Hicks_FM_R.ts 9/30/04 1:38 AM Page v For Dorothy 000_Hicks_FM_R.ts 9/30/04 1:38 AM Page vi 000_Hicks_FM_R.ts 9/30/04 1:38 AM Page vii Contents Preface to the Fordham University Press Edition, by Ron Powers ix Granville Hicks: Champion of the Small Town, by Warren Broderick xvii Author’s Preface xxxix small town i. -

Proletarian Literature, a N Unidentified Literary Object

L'Atelier 7.1 (2015) L'Institution de la littérature P ROLETARIAN LITERATURE, AN UNIDENTIFIED L ITERARY OBJECT BÉJA ALICE Sciences Po Lille Introduction 1. After Henry Roth’s Call it Sleep came out in 19341, New Masses published a review of the novel which ended by saying: “It is a pity that so many young writers drawn from the proletariat can make no better use of their working-class experience than as material for introspective and febrile novels.2” Although some left-wing critics (such as Edwin Seaver) and other Communist publications (like the Daily Worker) reviewed the book favorably, the New Masses article, coupled with the poor sales of the novel and the bankruptcy of its publisher, affected Roth and contributed to his long novelistic silence. Why reject a novel written by an “authentic” working class author, who lived in the Lower East side slums and whose parents were poor Jewish immigrants? Would not such a work be intrinsically “proletarian”? 2. The definition and status of proletarian literature in the United States gave rise to numerous debates; in many ways, proletarian literature was created by criticism, and buried by criticism. Spurred by the Comintern’s “third period” (1928-1935), it was defined and encouraged by the Communist party of the United States (CPUSA) and its cultural organs. But critics and writers ceaselessly debated its nature: should proletarian literature be written exclusively by writers who belonged to the proletariat? Should it deal only with subjects pertaining to the life of the working class? Should it have a specific style? With the Stalin trials, the German Soviet pact and the onset of the Cold War, most critics, agreeing with what Philip Rahv had written in 1939, dismissed proletarian literature as “the literature of a party disguised as the literature of a class3 ", and labeled the works it had given birth to as mere propaganda.