The Communist Party

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Form and Fantasy in Yiddish Literary Culture: Visions from Mexico City and Buenos Aires

Global Form and Fantasy in Yiddish Literary Culture: Visions from Mexico City and Buenos Aires by William Gertz Runyan A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Comparative Literature) in the University of Michigan 2019 Doctoral Committee: Professor Mikhail Krutikov, Chair Professor Tomoko Masuzawa Professor Anita Norich Professor Mauricio Tenorio Trillo, University of Chicago William Gertz Runyan [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-3955-1574 © William Gertz Runyan 2019 Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to my dissertation committee members Tomoko Masuzawa, Anita Norich, Mauricio Tenorio and foremost Misha Krutikov. I also wish to thank: The Department of Comparative Literature, the Jean and Samuel Frankel Center for Judaic Studies and the Rackham Graduate School at the University of Michigan for providing the frameworks and the resources to complete this research. The Social Science Research Council for the International Dissertation Research Fellowship that enabled my work in Mexico City and Buenos Aires. Tamara Gleason Freidberg for our readings and exchanges in Coyoacán and beyond. Margo and Susana Glantz for speaking with me about their father. Michael Pifer for the writing sessions and always illuminating observations. Jason Wagner for the vegetables and the conversations about Yiddish poetry. Carrie Wood for her expert note taking and friendship. Suphak Chawla, Amr Kamal, Başak Çandar, Chris Meade, Olga Greco, Shira Schwartz and Sara Garibova for providing a sense of community. Leyenkrayz regulars past and present for the lively readings over the years. This dissertation would not have come to fruition without the support of my family, not least my mother who assisted with formatting. -

Judaism and Its Effects on Moses Soyer's Paintings and Drawings

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU ETD Archive 2017 A Cultural Approach: Judaism and Its Effects on Moses Soyer’s Paintings and Drawings Rachel Arzuaga Cleveland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/etdarchive Part of the History Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Arzuaga, Rachel, "A Cultural Approach: Judaism and Its Effects on Moses Soyer’s Paintings and Drawings" (2017). ETD Archive. 965. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/etdarchive/965 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in ETD Archive by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CULTURAL APPROACH: JUDAISM AND ITS EFFECTS ON MOSES SOYER’S PAINTINGS AND DRAWINGS RACHEL ARZUAGA Bachelor of Arts in Art History Cleveland State University December 2013 Submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY at the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY August 2017 We hereby approve this thesis for Rachel Arzuaga Candidate for the Master of Arts in History degree for the Department of History and the Department of Art and the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY College of Graduate Studies _________________________________________________________________ Thesis Chairperson, Dr. Samantha Baskind _____________________________________________ -

The Southern California Library for Social Studies and Research: An

Gregory Alan-Kingman Hom, IS 281 Historical Research Methodology The Southern California Library for Social Studies and Research: An Independent Home for the Left Term paper written for Professor Maack’s class on Historical Research Methodology Introduction/Scope of the Presentation The Southern California Library for Social Studies and Research (SCL) is a library and archive situated in South Central Los Angeles. The SCL has regular presentations of speakers or films on topics relating to the community organizing efforts of Los Angeles activists. The SCL was initially the work of Emil Freed, the son of anarchists and brought up with the consciousness that the world needed to be changed. His political life led him to John Reed Clubs in 1929, which were associated with the Communist Party USA (CPUSA); he eventually became a member of the CPUSA, with which he was associated until his dying days. The library has a diverse collection today. It is in possession of most of the of the run of The California Eagle, one of the West Coast’s oldest African-American newspapers; the papers of labor unions; materials of the Jewish Left in Los Angeles; and materials on the Southern California branch of the Black Panther Party for Self Defense. Quite interesting is that later board members joined the New American Movement (NAM), an organization that attracted those who had left the CPUSA- papers relating to their involvement with that group are included in those later board members’ personal papers. The reality is that historical collections on Chican@s and Latin@s are less well represented, and still less on Asian-Americans. -

Lorne Bair :: Catalog 21

LORNE BAIR :: CATALOG 21 1 Lorne Bair Rare Books, ABAA PART 1: AFRICAN-AMERICAN HISTORY & LITERATURE 2621 Daniel Terrace Winchester, Virginia USA 22601 (540) 665-0855 Email: [email protected] Website: www.lornebair.com TERMS All items are offered subject to prior sale. Unless prior arrangements have been made, payment is expected with order and may be made by check, money order, credit card (Visa, MasterCard, Discover, American Express), or direct transfer of funds (wire transfer or Paypal). Institutions may be billed. Returns will be accepted for any reason within ten days of receipt. ALL ITEMS are guaranteed to be as described. Any restorations, sophistications, or alterations have been noted. Autograph and manuscript material is guaranteed without conditions or restrictions, and may be returned at any time if shown not to be authentic. DOMESTIC SHIPPING is by USPS Priority Mail at the rate of $9.50 for the first item and $3 for each additional item. Overseas shipping will vary depending upon destination and weight; quotations can be supplied. Alternative carriers may be arranged. WE ARE MEMBERS of the ABAA (Antiquarian Bookseller’s Association of America) and ILAB (International League of Antiquarian Book- sellers) and adhere to those organizations’ standards of professionalism and ethics. PART ONE African American History & Literature ITEMS 1-54 PART TWO Radical, Social, & Proletarian Literature ITEMS 55-92 PART THREE Graphics, Posters & Original Art ITEMS 93-150 PART FOUR Social Movements & Radical History ITEMS 151-194 2 PART 1: AFRICAN-AMERICAN HISTORY & LITERATURE 1. CUNARD, Nancy (ed.) Negro Anthology Made by Nancy Cunard 1931-1933. London: Nancy Cunard at Wishart & Co., 1934. -

'Crimes of Government': William Patterson, Civil Rights, and American Criminal Justice

“Crimes of Government” William Patterson, Civil Rights, and American Criminal Justice Alexandra Fay Undergraduate Thesis Department of History Columbia University April 4, 2018 Seminar Advisor: Elizabeth Blackmar Second Reader: Karl Jacoby Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Radical Beginnings ......................................................................................................................... 8 The Scottsboro Nine ..................................................................................................................... 17 The Trenton Six ............................................................................................................................ 32 Conclusion .................................................................................................................................... 52 Bibliography ................................................................................................................................. 63 2 Introduction “Why did you do this thing, Patterson?” demanded Channing Tobias. At the 1951 United Nations convention in Paris, Tobias represented the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Dignified, sixty-nine-year-old Tobias was an official American delegate. Bombastic, bespectacled, sixty-year-old William Patterson arrived in Paris despite the State Department’s best efforts to keep him away. His mission -

The Left Front : Radical Art in the "Red Decade," 1929-1940

LEFT FRONT EVENTS All events are free and open to the public Saturday, January 18, 2pm Winter Exhibition Opening with W. J. T. Mitchell Wednesday, February 5, 6pm Lecture & Reception: Julia Bryan-Wilson, Figurations Wednesday, February 26, 6pm Poetry Reading: Working Poems: An Evening with Mark Nowak Saturday, March 8, 2pm Film Screening and Discussion: Body and Soul with J. Hoberman Saturday, March 15, 2pm Guest Lecture: Vasif Kortun of SALT, Istanbul Thursday, April 3, 6pm Gallery Performance: Jackalope Theatre, Living Newspaper, Edition 2014 Saturday, April 5, 5pm Gallery Performance: Jackalope Theatre, Living Newspaper, Edition 2014 Wednesday, April 16, 2014, 6pm Lecture: Andrew Hemingway, Style of the New Era: THE LEFT FRONT John Reed Clubs and Proletariat Art RADICAL ART IN THE "RED DECADE," 1929-1940 Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art Northwestern University 40 Arts Circle Drive, Evanston, IL, 60208-2140 www.blockmuseum.northwestern.edu Generous support for The Left Front is provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art, as well as the Terra Foundation on behalf of William Osborn and David Kabiller, and the MARY AND LEIGH BLOCK MUSEUM OF ART Myers Foundations. Additional funding is from the Carlyle Anderson Endowment, Mary and Leigh Block Endowment, the Louise E. Drangsholt Fund, the Kessel Fund at the NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSIty Block Museum, and the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency. theleftfront-blockmuseum.tumblr.com January 17–June 22, 2014 DIRECTOR'S FOREWORD The Left Front: Radical Art in the “Red Decade”, 1929–1940 was curated by John Murphy undergraduate seminar that focused on themes in the exhibition and culminated in and Jill Bugajski, doctoral candidates in the Department of Art History at Northwestern student essays offering close examinations of particular objects from the show. -

Hungarian Studies Review, 29, 1-2 (1992): 7-27

A Communist Newspaper for Hungarian-Americans: The Strange World of the Uj Elore Thomas L. Sakmyster On November 6, 1921 the first issue of a newspaper called the Uj Elore (New Forward) appeared in New York City.1 This paper, which was published by the Hungarian Language Federation of the American Communist Party (then known as the Workers Party), was to appear daily until its demise in 1937. With a circulation ranging between 6,000 and 10,000, the Uj Elore was the third largest newspaper serving the Hungarian-American community.2 Furthermore, the Uj Elore was, as its editors often boasted, the only daily Hungarian Communist newspaper in the world. Copies of the paper were regularly sent to Hungarian subscri- bers in Paris, Berlin, Vienna, Moscow, Buenos Aires, and, on occasion, even smuggled into Budapest. The editors and journalists who produced the Uj Elore were a band of fervent ideologues who presented and inter- preted news in a highly partisan and utterly dogmatic manner. Indeed, this publication was quite unlike most American newspapers of the time, which, though often oriented toward a particular ideology or political party, by and large attempted to maintain some level of objectivity. The main purpose of Uj Elore, as later recalled by one of its editors, was "not the dissemination of news but agitation and propaganda."3 The world as depicted by writers for the Uj Elore was a strange and distorted one, filled with often unintended ironies and paradoxes. Readers of the newspaper were provided, in issue after issue, with sensational and repetitive stories about the horrors of capitalism and fascism (especially in Hungary and the United States), the constant threat of political terror and oppression in all countries of the world except the Soviet Union, and the misery and suffering of Hungarian-American workers. -

New Masses Index 1926 - 1933 New Masses Index 1934 - 1935 New Masses Index 1936

NEW MASSES INDEX 1936 NEW MASSES INDEX NEW MASSES INDEX 1936 By Theodore F. Watts Copyright 2007 ISBN 0-9610314-0-8 Phoenix Rising 601 Dale Drive Silver Spring, Maryland 20910-4215 Cover art: William Sanderson Regarding these indexes to New Masses: These indexes to New Masses were created by Theodore Watts, who is the owner of this intellectual property under US and International copyright law. Mr. Watts has given permission to the Riazanov Library and Marxists.org to freely distribute these three publications… New Masses Index 1926 - 1933 New Masses Index 1934 - 1935 New Masses Index 1936 … in a not for profit fashion. While it is my impression Mr. Watts wishes this material he created be as widely available as possible to scholars, researchers, and the workers movement in a not for profit fashion, I would urge others seeking to re-distribute this material to first obtain his consent. This would be mandatory, especially, if one wished to distribute this material in a for sale or for profit fashion. Martin H. Goodman Director, Riazanov Library digital archive projects January 2015 Patchen, Rebecca Pitts, Philip Rahv, Genevieve Taggart, Richard Wright, and Don West. The favorite artist during this two-year span was Russell T. Limbach with more than one a week for the run. Other artists included William Gropper, John Mackey, Phil Bard, Crockett Johnson, Gardner Rea, William Sanderson, A. Redfield, Louis Lozowick, and Adolph Dehn. Other names, familiar to modem readers, abound: Bernarda Bryson and Ben Shahn, Maxwell Bodenheim, Erskine Caldwell, Edward Dahlberg, Theodore Dreiser, Ilya Ehrenberg, Sergei Eisenstein, Hanns Eisler, James T. -

"A Road to Peace and Freedom": the International Workers Order and The

“ A ROAD TO PEACE AND FREEDOM ” Robert M. Zecker “ A ROAD TO PEACE AND FREEDOM ” The International Workers Order and the Struggle for Economic Justice and Civil Rights, 1930–1954 TEMPLE UNIVERSITY PRESS Philadelphia • Rome • Tokyo TEMPLE UNIVERSITY PRESS Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19122 www.temple.edu/tempress Copyright © 2018 by Temple University—Of The Commonwealth System of Higher Education All rights reserved Published 2018 All reasonable attempts were made to locate the copyright holders for the materials published in this book. If you believe you may be one of them, please contact Temple University Press, and the publisher will include appropriate acknowledgment in subsequent editions of the book. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Zecker, Robert, 1962- author. Title: A road to peace and freedom : the International Workers Order and the struggle for economic justice and civil rights, 1930-1954 / Robert M. Zecker. Description: Philadelphia : Temple University Press, 2018. | Includes index. Identifiers: LCCN 2017035619| ISBN 9781439915158 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781439915165 (paper : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: International Workers Order. | International labor activities—History—20th century. | Labor unions—United States—History—20th century. | Working class—Societies, etc.—History—20th century. | Working class—United States—Societies, etc.—History—20th century. | Labor movement—United States—History—20th century. | Civil rights and socialism—United States—History—20th century. Classification: LCC HD6475.A2 -

“To Work, Write, Sing and Fight for Women's Liberation”

“To work, write, sing and fight for women’s liberation” Proto-Feminist Currents in the American Left, 1946-1961 Shirley Chen A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF SCIENCE WITH HONORS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN March 30, 2011 Advised by Professor Howard Brick For my mother Table of Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... ii Introduction...................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter I: “An End to the Neglect” ............................................................................ 10 Progressive Women & the Communist Left, 1946-1953 Chapter II: “A Woman’s Place is Wherever She Wants it to Be” ........................... 44 Woman as Revolutionary in Marxist-Humanist Thought, 1950-1956 Chapter III: “Are Housewives Necessary?” ............................................................... 73 Old Radicals & New Radicalisms, 1954-1961 Conclusion .................................................................................................................... 106 Bibliography ................................................................................................................. 111 Acknowledgements First, I am deeply grateful to my adviser, Professor Howard Brick. From helping me formulate the research questions for this project more than a year ago to reading last minute drafts, his -

The Devil Wears Prado: a Look at the Design Piracy Prohibition Act and the Extension of Copyright Protection to the World of Fashion, 35 Pepp

Pepperdine Law Review Volume 35 | Issue 1 Article 4 12-15-2007 The evD il Wears Prado: A Look at the Design Piracy Prohibition Act and the Extension of Copyright Protection to the World of Fashion Lynsey Blackmon Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/plr Part of the Intellectual Property Commons Recommended Citation Lynsey Blackmon The Devil Wears Prado: A Look at the Design Piracy Prohibition Act and the Extension of Copyright Protection to the World of Fashion, 35 Pepp. L. Rev. 1 (2008) Available at: http://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/plr/vol35/iss1/4 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pepperdine Law Review by an authorized administrator of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Devil Wears Prado:' A Look at the Design Piracy Prohibition Act and the Extension of Copyright Protection to the World of Fashion I. INTRODUCTION II. UNDERSTANDING THE FASHION INDUSTRY III. FASHION'S CURRENT PROTECTION A. Design Patents B. Trademark IV. THE QUEST FOR COPYRIGHT: THE HISTORY OF FASHION DESIGNS AND THE COPYRIGHT ACT V. THE DESIGN PIRACY PROHIBITION ACT A. House Resolution 5055 1. Provisions of the Proposal 2. Infringement B. Will It Work? 1. The Players a. Designers b. Courts c. Consumers 2. The Art 3. The Economy VI. WHAT WILL IT TAKE: SUGGESTIVE MODIFICATIONS VII. CONCLUSION 1. Many counterfeit and knockoff artists attempt to circumvent the little protection provided fashion designs by altering registered trademarks. -

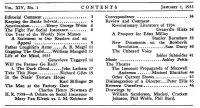

Vol. XIV, No. 1 CONTENTS JANUARY 1, 1935 Editorial

VoL. XIV, No. 1 CONTENTS JANUARY 1, 1935 Editorial Comment • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • .. ..• 3 Correspondence • . • • . • • . • • . • • • • • • . • . • • 34 Keeping the Banks Solvent.............. 6 Review and Comment Americanism .•.••••. Henry George Weiss 6 Revolutionary Literature of 1934 The Fight For Social Insurance. • • • . • • • • 8 Granville Hicks 36 One Year of the Weekly New Masses A Prospect for Edna Millay A Statement to Our Readers and an · Stanley Burnshaw 39 Appeal • • ••••• ••••••. .• • • • . • • ••• 9 New Documents on the Bolshevik Father Coughlin's Army .••.. A. B. Magi! 11 Revolution ...•..••.•.•• Sam Darcy 40 Gagging The Guild •••• William Mangold 15 The Unheard Voice Life of the Mind, 1935 Isidor Schneider 41 Genevieve Taggard 16 Music .................... Ashley Pettis Will the Farmer Go Red? The Theatre 5. The Dark Cloud ...... John Latham 17 The Innocent Propaganda of Maxwell Take This Hope .......•... Richard Giles 19 Anderson ••....• Michael Blankfort 44 In the Nazis' Torture House Other Current Shows .•.••••.••••..•• 45 Karl Billinger 20 Disintegration of a Director ••. Peter Ellis 45 The Man at the Factory Gate Between Ourselves • • • • • • • • . • • • . • • • • . • • . 46 Charles Henry Newman 27 Drawings by H. R. 7598-A Debate on Social Insurance William Sanderson, Mackey, Crockett Mary Van Kleeck ,ys. I. M. Rubinow 28 Johnson, Phil Wolfe, Phil Bard. VoL. XIV, No. 2 CONTENTS JANUARY 8, 1935 Editorial Comment . • . • . • • . 3 Arming the Masses .••.••••. Ben Field 25 Betrayal by the N.A.A.C.P. •. • . • 6 American Decadence Mapped Terror in "Liberal" Wisconsin........... 8 .Samuel Levenson 25 The Truth About the Crawford Case Fire on the Andes •••... Frank Gordon 26 Martha Gruening 9 Brief Review ••••••••••••••• , • • • . • • 27 Moscow Street. ....... Charles B. Strauss 15 Book Notes •••••••••••••••.••.•••••• 27 The Auto Workers Face 1935 Art A.