Hungarian Studies Review, 29, 1-2 (1992): 7-27

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Aspects of Life and Politics in the United States of America in 19321)

M. S. VENKATARAMANI SOME ASPECTS OF LIFE AND POLITICS IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA IN 19321) To the present generation of young Americans the so-called two party system appears to be an almost unshakeable and permanent feature of the nation's polity. Several well-known American liberals (as, for instance, Senator Paul Douglas of Illinois and Walter Reuther, head of the powerful United Automobile Workers), who, in earlier years had reposed little faith in the Republican and Democratic parties, have gradually veered round to the view that the quest for reform must be pursued within the framework of the two major political parties. "Third parties" on the American scene have become virtually skele- tonized for various reasons and their plans and platforms receive scant notice at the hands of the media of mass communication. With the advent of good times during the war and post-war years, organizations advocating a radical reconstruction of the social and economic order have found a progressively shrinking audience. Radicalism among the intelligentsia has become a factor of minor significance. Will there be any important changes in such a state of affairs if the current business "recession" continues much longer or intensifies? Do "bad times" favor the growth of militant parties of protest and dissent? Few students of the American scene expect that in the foreseeable future there will be any widespread move away from the two traditional parties. It is interesting in this connection to examine the developments in the United States a quarter of a century ago when the nation was plunged into one of the most serious economic crises in its annals. -

Lorne Bair :: Catalog 21

LORNE BAIR :: CATALOG 21 1 Lorne Bair Rare Books, ABAA PART 1: AFRICAN-AMERICAN HISTORY & LITERATURE 2621 Daniel Terrace Winchester, Virginia USA 22601 (540) 665-0855 Email: [email protected] Website: www.lornebair.com TERMS All items are offered subject to prior sale. Unless prior arrangements have been made, payment is expected with order and may be made by check, money order, credit card (Visa, MasterCard, Discover, American Express), or direct transfer of funds (wire transfer or Paypal). Institutions may be billed. Returns will be accepted for any reason within ten days of receipt. ALL ITEMS are guaranteed to be as described. Any restorations, sophistications, or alterations have been noted. Autograph and manuscript material is guaranteed without conditions or restrictions, and may be returned at any time if shown not to be authentic. DOMESTIC SHIPPING is by USPS Priority Mail at the rate of $9.50 for the first item and $3 for each additional item. Overseas shipping will vary depending upon destination and weight; quotations can be supplied. Alternative carriers may be arranged. WE ARE MEMBERS of the ABAA (Antiquarian Bookseller’s Association of America) and ILAB (International League of Antiquarian Book- sellers) and adhere to those organizations’ standards of professionalism and ethics. PART ONE African American History & Literature ITEMS 1-54 PART TWO Radical, Social, & Proletarian Literature ITEMS 55-92 PART THREE Graphics, Posters & Original Art ITEMS 93-150 PART FOUR Social Movements & Radical History ITEMS 151-194 2 PART 1: AFRICAN-AMERICAN HISTORY & LITERATURE 1. CUNARD, Nancy (ed.) Negro Anthology Made by Nancy Cunard 1931-1933. London: Nancy Cunard at Wishart & Co., 1934. -

New Masses Index 1926 - 1933 New Masses Index 1934 - 1935 New Masses Index 1936

NEW MASSES INDEX 1936 NEW MASSES INDEX NEW MASSES INDEX 1936 By Theodore F. Watts Copyright 2007 ISBN 0-9610314-0-8 Phoenix Rising 601 Dale Drive Silver Spring, Maryland 20910-4215 Cover art: William Sanderson Regarding these indexes to New Masses: These indexes to New Masses were created by Theodore Watts, who is the owner of this intellectual property under US and International copyright law. Mr. Watts has given permission to the Riazanov Library and Marxists.org to freely distribute these three publications… New Masses Index 1926 - 1933 New Masses Index 1934 - 1935 New Masses Index 1936 … in a not for profit fashion. While it is my impression Mr. Watts wishes this material he created be as widely available as possible to scholars, researchers, and the workers movement in a not for profit fashion, I would urge others seeking to re-distribute this material to first obtain his consent. This would be mandatory, especially, if one wished to distribute this material in a for sale or for profit fashion. Martin H. Goodman Director, Riazanov Library digital archive projects January 2015 Patchen, Rebecca Pitts, Philip Rahv, Genevieve Taggart, Richard Wright, and Don West. The favorite artist during this two-year span was Russell T. Limbach with more than one a week for the run. Other artists included William Gropper, John Mackey, Phil Bard, Crockett Johnson, Gardner Rea, William Sanderson, A. Redfield, Louis Lozowick, and Adolph Dehn. Other names, familiar to modem readers, abound: Bernarda Bryson and Ben Shahn, Maxwell Bodenheim, Erskine Caldwell, Edward Dahlberg, Theodore Dreiser, Ilya Ehrenberg, Sergei Eisenstein, Hanns Eisler, James T. -

Download Legal Document

2:19-cv-03083-RMG Date Filed 11/25/19 Entry Number 35-16 Page 1 of 33 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF SOUTH CAROLINA CHARLESTON DIVISION Linquista White, et al., Plaintiffs, v. Civil Action No. Kevin Shwedo, et al., 2:19-cv-03083-RMG Defendants. DECLARATION OF BARBRA KINGLSEY, Ph.D. I, Barbra Kingsley, Ph.D., declare as follows: I. QUALIFICATIONS 1. I am an expert in the fields of information design and plain language. Information design is a professional field focused on developing written communication that fosters efficient and effective understanding for the average reader. Plain language is a professional field focused on fostering written communication that is clear and simple so that average readers can find, understand, and appropriately use the information they need. My curriculum vitae, which sets forth my education, professional experiences, publications, and awards, is attached as Appendix A. A. Professional Experience 2. For more than 24 years, I have focused on providing education, consulting, research and training on the use of plain language and effective information design in written communications to enhance reader comprehension and to help readers make appropriate, informed decisions based on their understanding of written communications. 3. I am the co-founder of Kleimann Communication Group, a firm that provides consulting, 1 2:19-cv-03083-RMG Date Filed 11/25/19 Entry Number 35-16 Page 2 of 33 training, and research services in information design and plain language.1 4. I am also the Chair of the Center for Plain Language (“CPL”), a national advocacy organization championing clear communication. -

Memories of C.E. Ruthenberg by Bill Dunne: Excerpt from an Interview Conducted by Oakley C. Johnson, 1940

Memories of C.E. Ruthenberg by Bill Dunne: Excerpt from an Interview Conducted by Oakley C. Johnson, 1940 Handwritten index cards in C.E. Ruthenberg Papers, Ohio Historical Society, Box 9, Folder 2, microfilm reel 5. Very heavily edited by Tim Davenport. C.E. Ruthenberg was what you might call the American spokes- man for the foreign elements. The Slavs, Letts [Latvians], Poles, etc. gathered around Ruthenberg. As late as 1927 we were still publishing 22 papers — 3 Finnish dailies, 2 Lithuanian dailies, 1 Italian daily, 1 German daily, and a number of weeklies. But Ruthenberg didn’t have American contacts outside of Chicago. I considered Ruthenberg an uninspired person. He was no scholar, he couldn’t write — but he was a gentleman. His relations with the Party were always very formal. Ruthenberg’s big mistake was to allow himself to be used by the Lovestone caucus. And he was monstrously vain! Well, personally vain anyway. He would become personally offended if he didn’t get the deference which he expected. I first met Ruthenberg in our apartment at 11 St. Luke’s Place in New York City in 1922.1 I was the first editor of the weekly Worker.2 Ruthenberg was just out of prison.3 Caleb Harrison was the secretary of The Worker, which was the party’s legal daily. Henryk Walecki, the CI Rep, was there, also Boris Reinstein, and Charlie Johnson [Karlis Janson] — a Lett,.4 now in Moscow, and Lovestone, as well as Will 1 Apparently the secret location of CPA party headquarters. 2 Formerly The Toiler and prior to that The Ohio Socialist. -

Tamwag Fawf000053 Lo.Pdf

A LETTER FROM AMERICA By Pam Flett- WILL be interested in hearing what you think of Roosevelt’s foreign policy. When he made the speech at Chicago, I was startled and yet tremendously thrilled. It certainly looks as if something will have to be done to stop Hitler and Mussolini. But I wonder what is behind Roosevelt's speech. What does he plan to do? And when you get right down to it, what can we do? It’s easy to say “Keep out of War,” but how to keep out? TREAD in THE FIGHT that the ‘American League is coming out with a pamphlet by Harty F. Ward on this subject—Neutrality llready and an American sent in Peace my order. Policy. You I’ve know you can hardly believe anything the newspapers print these days_and I’m depending gare end ors on hare caer Phiets. For instance, David said, hational, when we that read i¢ The was Fascist_Inter- far-fetched and overdone. But the laugh’s for on him, everything if you can that laugh pamphlet at it- Fe dered nigiae th fact, the pamphiot is more up- iendalainow than Fodey'eipener eso YOUR NEXT YEAR IN ART BUT I have several of the American League pamphlets—Women, War and Fascism, Youth Demands WE'VE stolen a leaf from the almanac, which not only tells you what day it is but gives you Peace, A Blueprint for Fascism advice on the conduct of life. Not that our 1938 calendar carries instructions on planting-time (exposing the Industrial Mobiliza- tion Plan)—and I’m also getting But every month of it does carry an illustration that calls you to the struggle for Democracy and Why Fascism Leads to War and peace, that pictures your fellow fighters, and tha gives you a moment’s pleasure A Program Against War and Fascism. -

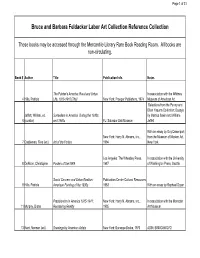

Bruce and Barbara Feldacker Labor Art Collection Reference Collection

Page 1 of 31 Bruce and Barbara Feldacker Labor Art Collection Reference Collection These books may be accessed through the Mercantile Library Rare Book Reading Room. All books are non-circulating. Book # Author Title Publication Info. Notes The Painter's America: Rural and Urban In association with the Whitney 4 Hills, Patricia Life, 1810-1910 [The] New York: Praeger Publishers, 1974 Museum of American Art Selections from the Penny and Elton Yasuna Collection; Essays Jeffett, William, ed. Surrealism in America During the 1930s by Martica Sawin and William 6 (curator) and 1940s FL: Salvador Dali Museum Jeffett With an essay by Guy Davenport; New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., from the Museum of Modern Art, 7 Castleman, Riva (ed.) Art of the Forties 1994 New York Los Angeles: The Wheatley Press, In association with the University 8 DeNoon, Christopher Posters of the WPA 1987 of Washington Press, Seattle Social Concern and Urban Realism: Publication Center Cultural Resources, 9 Hills, Patricia American Painting of the 1930s 1983 With an essay by Raphael Soyer Precisionism in America 1915-1941: New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., In association with the Montclair 11 Murphy, Diana Reordering Reality 1995 Art Museum 13 Kent, Norman (ed.) Drawings by American Artists New York: Bonanza Books, 1970 ASIN: B000G5WO7Q Page 2 of 31 Slatkin, Charles E. and New York: Oxford University Press, 14 Shoolman, Regina Treasury of American Drawings 1947 ASIN: B0006AR778 15 American Art Today National Art Society, 1939 ASIN: B000KNGRSG Eyes on America: The United States as New York: The Studio Publications, Introduction and commentary on 16 Hall, W.S. -

NELSON ROCKEFELLER-DIEGO RIVERA CLASH and MAKING of the US ART CULTURE DURING the 1930’S

MURALS SPEAK LOUDER THAN WORDS: NELSON ROCKEFELLER-DIEGO RIVERA CLASH AND MAKING OF THE US ART CULTURE DURING THE 1930’s A Master’s Thesis By GÖZDE PINAR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY İHSAN DOĞRAMACI BİLKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA September 2013 To My Parents…. MURALS SPEAK LOUDER THAN WORDS: NELSON ROCKEFELLER-DIEGO RIVERA CLASH AND MAKING OF THE US ART CULTURE DURING THE 1930’S Graduate School of Economics and Social Sciences of İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University by GÖZDE PINAR In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY İHSAN DOĞRAMACI BİLKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA September 2013 I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in History. -------------------------- Asst. Prof. Edward P. Kohn Thesis Supervisor I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in History. -------------------------- Asst. Prof. Kenneth Weisbrode Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in History. -------------------------- Asst. Prof. Dennis Bryson Examining Committee Member Approved by the Graduate School of Economics and Social Sciences. -------------------------- Prof. Dr. Erdal Erel Director ABSTRACT MURALS SPEAK LOUDER THAN WORDS: NELSON ROCKEFELLER-DIEGO RIVERA CLASH AND MAKING OF THE US ART CULTURE DURING THE 1930’S Pınar, Gözde M.A., Department of History, Bilkent University Supervisor: Assist. -

ED057706.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 057 706 rt. 002 042 AWTMOR Moskowitz, Solomon TITLP Hebrew for 'c,econlAty Schools. INSTTTUTIOW Wew York State Education Dept., Albany. Pureau of Secondary Curriculum !Development. IMB DAT!!! 71 wOTE 143n. EDRS PRICE XF-30.65 HC-$6.56 DESCRIPTOPS Articulation (Program); Audiolingual skills; Sasic Skills; Bibliographies; Cultural Education: Hebrew; Language Instruction; Language Laboratories; Language Learning Levels; Language Programs; Language skills; Lesson Plans; Manuscript Writing (Handlettering); Pattern Drills (Language); Secondary Schools; *Semitic Languages; *Teaching Guides ABSTRACT This teacher's handbook for Hebrew instruction in secondary Schools, designed for use in public schools, is patterned after New York state Education Department handbooks for French, seanieho and German* Sections include:(1) teaching the four skills, (2) speaking,(3) audiolingual experiences,(4) suggested content and topics for audioLingual experiences, (15) patterns for drill,(6) the toxtbook in audiolingual presentation, (7) language laboratories, (0) reading and writing,(9) culture,(10) articulation, (11) vocabulary, (12) structures for four- and six-year sequences,(13) the Hebrew alphabet,(14) model lessons-- grades 10 and 11, and (15) student evaluation. A glossary, bibliography, and appendix illustrating Hebrew calligraphy are included. (m) HEBREW For Secondary Schools U DISPANTNENT Of NIA1.11N. wsurang EDUCATION OfFICE OF EDUCATION HOS DOCUNFOCI HAS SUN ExACTLy As mom MIA SKINSOOUCED onsouganoft ottroutkvotoYH PERsON op vim o OeusNONS STATEDsT mon or wows Nipasturfr Offs Cut.00 NOT NECES lumps+ Poo/no% OR PoucvOFFICE OF f DU The University of the State of New York THE STATE EDUCATION DEPARTMENT Bureau of Secondary Curriculum Development/Albany/1971 1 THE UNIVERSITY OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK Regents of the University (with years when terms expire) 1984 Joseph W. -

The Independent Voice of the Visual Arts Volume 35 Number 1, October 2020

The Independent Voice of the Visual Arts Volume 35 Number 1, October 2020 Established 1973 ART & POLITICS $15 U.S. ART AND POLITICS COVER CREDITS Front: Gran Fury, When A Government Turns Its Back On Its People; Joan_de_art & crew, Black Lives Matter;Hugo Gellert: Primary Accumulation 16 Back: Chris Burke and Ruben Alcantar, Breonna Taylor, Say Her Name!!!, Milwaukee; Sue Coe, Language of the Dictator; Lexander Bryant, Opportunity Co$t, Gran Fury, Kissing Doesn’t Kill. Established 1973 Vol. 35, No. 1 October 2020 Contents ARTICLES 3 Art and Politics: 39 COVID-19 and the Introduction Creative Process(es) Two more Interviews 5 Art of the Black Lives from Chicago Matter Movement Michel Ségard compiles BLM-related 39 Introduction art from across the country. 40 Stevie Hanley Stevie Hanley is a practicing artist and 11 It Can Happen Here— an instructor at the Art Institute of An Anti-Fascism Project Chicago. He is also the organizer of the Siblings art collective. Stephen F. Eisenman and Sue Coe mount their multimedia resistance to the Donald Trump administration. 43 Patric McCoy Patric McCoy is an art collector and 19 Have you given up hope co-founder of the arts non-profit for a cure? Diasporal Rhythms, an organization Paul Moreno revisits Gran Fury, an focused on the art of the African ‘80s art collective that responded to Diaspora. AIDS in unabashedly political ways. 25 In Tennessee, Art Itself Is Protest Kelli Wood leads us through Nashville’s art scene, advocating change to the tune of Dolly Parton’s “Down on Music REVIEWS Row.“ 47 “Problem Areas” 32 Iconoclasm Then Luis Martin/The Art Engineer reviews the first solo show from painter Paul and Now Moreno at New York’s Bureau of Gen- Thomas F.X. -

Down from the Ivory Tower: American Artists During the Depression

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1982 Down from the ivory tower: American artists during the Depression Susan M. Eltscher College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Eltscher, Susan M., "Down from the ivory tower: American artists during the Depression" (1982). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625189. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-a5rw-c429 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DOWN FROM THE IVORY TOWER: , 4 ‘ AMERICAN ARTISTS DURING THE DEPRESSION A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Susan M. Eltscher APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts ^jiuu>0ur> H i- fc- bbcJ^U i Author Approved, December 1982 Richard B. Sherman t/QOJUK^r Cam Walker ~~V> Q ' " 9"' Philip J/ Fuiyigiello J DEDICATION / ( \ This work is dedicated, with love and appreciation, to Louis R. Eltscher III, Carolyn S. Eltscher, and Judith R. Eltscher. ( TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACRONYMS................... .......................... v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.......................................... -

Plat..Kl SOCIALIST PARTY

’ i!Jational Constitution Plat..kl of the SOCIALIST PARTY 1917 National Office, Socialist Party 803 W. Madison Street CHICAGO, ILL. The Working Clti is only as strong as it makes itself by thorough political and economic organization. Labor’s strength lies in its or- ganized activity, with every- one doing his share. Every member of the Socialist Party should enlist in a con- tinuous campaign for new members. Let no opportunity go by to get new members. Qnly through organization can we grow strong and be- come free. Workers of allcountries unite; you have nothing to lose but your chains; you have a world to gain-Marx. ., CONSTITUTION ARTICLE 1. Name. Sec. 1. The name of this organization shall be the Socialist Party, except in such states where a different name has or may become a legal require- ment. i ARTICLE II. Membership. Sec. 1. Every person, resident of the United States of the age of eighteen years and upward, without discrimination as to sex, race, color or creed, who has severed his connection with all other political parties and political organizations, and subscribes to the principles of the Socialist Party, including political actlon and unrestricted political rights for both sexes, shall be eligible to membership in the party. Sec. 2. No erson holding an elective public office by gift o P any party or organization other than the Socialist Party shall be eligible to mem- bership in the Socialist Party without the consent of his state organization; nor shall any member of the party accept or hold any a pointive public office, honorary or remunerative ( t-.